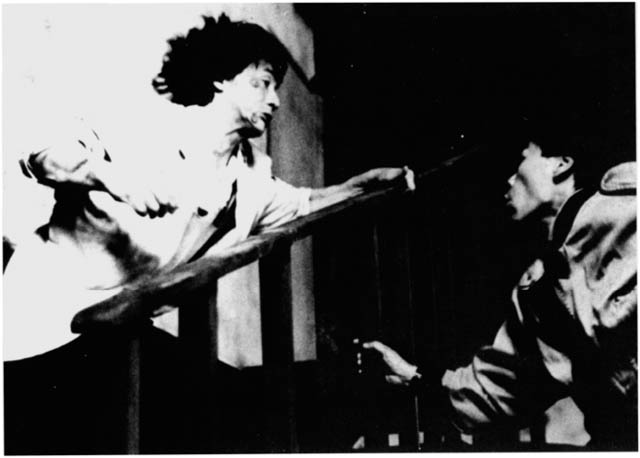

A new kind of hero: Project A’s Dragon Ma gets drenched courtesy of Yuen Biao. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Film historians, critics, and everyday filmgoers all have different ideas as to what defines a genre. A textbook would describe it as an art distinguished by a definite style, form, or content. The ambiguity of the word definite is perhaps what generates opposing views on the subject. Can Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly be categorized in the same way as Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven? In a critical study of genre film noir, critic Rick Altman makes the intriguing comment, “Genres were always—and continue to be—treated as if they spring full-blown from the head of Zeus.” In other words, while similar traits may exist, a genre is dictated by syntax rather than a loose collection of coincidental factors. Gene Roddenberry patterned Star Trek after the Great American Western, yet the science fiction series can hardly be placed in the western genre since its themes and setting are not those of a western. Where is the line drawn?

If one assumes that genres do exist, then Jackie Chan deserves one of his own. He never let himself be assimilated into the preexisting genres of old, Chinese or American, once he could gain the control to step out from the shadows of the kung fu genre. During the eighties, Hong Kong cinematic genres were based on hopping vampires, gambling, triads (Chinese gangs), and fighting females. Chan simply moved to the modern world and chose to administer his talents in a forum that no one could ever duplicate. After all, it was easy for people to reproduce his kung fu comedies of the late seventies. His collaborations with Sammo Hung were strong, but they were really just part of an experimental stage, and Chan had found the key to making his audience happy. Jackie Chan would make Jackie Chan films—and no one else’s.

Very few people can be noted for self-created genres, because control is the key ingredient in developing this type of genre. Unfortunately, the Charlie Chaplins and the Buster Keatons of the world don’t exist anymore because control has been taken out of the hands of the filmmakers themselves. In Hollywood creative forces have been silenced by red tape: countless meetings, focus groups, other marketing efforts, and lack of synergy have stripped away the essence of what makes an inventor invent. When sound came into play, Buster Keaton’s style of filmmaking became untranslatable. Improvisation was traded for structured scripting, dance numbers and songs replaced his inventive sight gags, and he was given specific characters.

In Hong Kong, however, Jackie Chan can do whatever he pleases. He exerts the same control that the Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin of old possessed. Chan has an all-encompassing knowledge of every cinematic process, whether it be directing, editing, acting, writing, or fight choreography. Acclaim from his fans worldwide is the fuel that keeps Chan’s vision alive. His audience expects a lot, and Chan has no problem in meeting their expectations. Exhaustive shoots, injuries, and sticking to budgets are really of no concern to him as long as he feels that whatever film he is working on at the time is better than the one before it. “Budget? There is no such thing as a budget for a Jackie Chan film!” says Russell Cawthorne, longtime Golden Harvest representative. Since Chan signed with Golden Harvest in 1980, not one of his films has lost money. Chan’s style of filmmaking isn’t about trying different characters, making a point about society’s wrongs, or even rethinking the action genre’s stagnant storylines. It seems contradictory that control could foster creativity, yet in those films over which he had control, Chan carved out his own genre.

The Jackie Chan genre features an unconventional hero using unconventional means to solve conflicts in an unconventional world. The unconventional hero is an underdog forged by the combination of three elements: the physical abilities of Chan himself, the writing of Edward Tang, and the inspiration of the great silent comedians. As mentioned before, Chan’s physical features would virtually make it impossible for him to try and act like a Sylvester Stallone or a Jean-Claude Van Damme. His character isn’t embodied in classical hero aesthetics. He is neither vain nor pretentious, since such traits would make him look ridiculous. And without those stereotypically masculine ideals, the characters he plays can never be in charge or assume any kind of power. Chan is a simple working man.

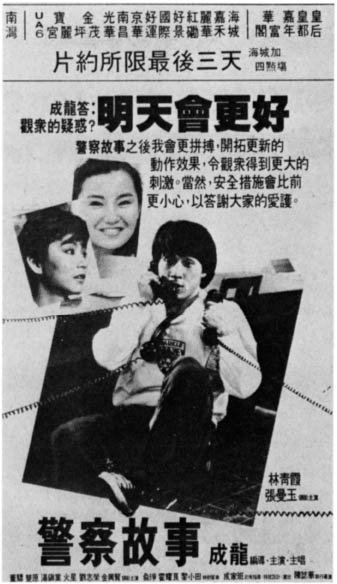

In Police Story (1985), when Chan arrests a drug lord at the beginning of the film, his superiors give him specific lines to say for a press conference. He rambles on, even waving to the camera because he does not understand the fame associated with duty. When his character is praised for being more than what he is, Chan will take credit but won’t necessarily believe in his heart that he is ever really that good. Chan is only the hero when he is pushed into being one. All of Chan’s genre-specific characters work within the guidelines of a working man rather than the man who is above it.

When American cinema created the action genre, it also worked all of its supposed heroes into a corner. In the past decade, it would be nearly impossible to find even one protagonist who is not a detective, regular cop, or some kind of secret agent. In Under Siege (1988) Steven Seagal plays a cook, but no one would believe that a cook could be a hero unless he also happens to be an ex-Green Beret. At some point in every action film, there has to be an explanation as to how and why the hero does what he does. The audience is led to believe that only the detective or other such character can come to the rescue and save the day.

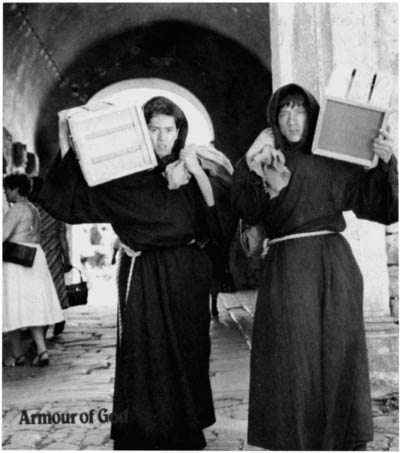

Jackie Chan, however, can be a lawyer (Dragons Forever), a sailor (Project A), an archaeologist (Armour of God), or even an out-of-work lad (Mr. Canton and Lady Rose). In Mr. Nice Guy, he plays a chef, but not even the head chef. “Chan felt that the head chef would be too much for an underdog character, so he opted for an assistant chef,” says Chua Lam, the film’s producer. Even with this range of professions, the audience knows and expects Chan to be a man of action, without any kind of explanation necessary.

Chan in the modern world: Police Story II. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Since Chan’s characters can’t be more than what an underdog can be, many times he assumes other roles to jump outside of his regular-guy persona. In Police Story II Chan poses as a geek—dressed in glasses, a mustache, and a stuffy jacket—to coax an explosives dealer into revealing his stash. This guise frees him to act forcibly in clear contradiction to his normal character. As a result, one scene has the perpetrator and his girlfriend sitting on either side of Chan. As they both start jabbering, Chan only has to lose his patience in listening to them before he commences to punch him and slap her, going back and forth until they are silenced. In Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, when Chan acts as a good Samaritan by helping a man chased by gunfire, he is given a leadership role over a group of mobsters. While he still retains his innocence, Chan can act as a leader, if only to turn the mobsters away from the violence that surrounds them. A third example is found in Young Master when Chan assumes the role of an eccentric beggar to fight the master’s two lackeys. His happy-go-lucky character would never walk up and draw someone into a fight, but an alternative persona might. This keeps the Jackie Chan character from being static. In contrast, think of Bruce Lee in Chinese Connection. Lee’s characterization rested on being this rigid, powerful ruffian. After posing as a pedicab driver and dressing up as an old man, Lee finally relaxes in portraying a dim-witted repairman. He laughs, walks calmly, and shows no attitude walking into the offices of the Japanese whom he despises so much.

During the period between Young Master and Dragon Lord, Chan found inspiration in the silent comedians of the 1920s, notably Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and to a lesser extent Charlie Chaplin. All three of these clowns of the silent screen had no other choice but to use their bodies to bring laughter to the audience since intricate storylines and dialogue could not be worked into the linear narrative. Chan pulls out Keaton’s invention of controlling his body within a given environment, Lloyd’s intense facial expressions in response to his incredible physical feats, and Chaplin’s juggling act of smaller, more complex gags. Chan was surprised by the universal comedic elements in their films. Since his English was rough at the time, he was able to enjoy these classics—forgotten by many who are spoiled by Hollywood’s state-of-the-art special effects. With the absence of dialogue, Chan quickly surmised the importance of music in creating rhythm in the action. Fred Astaire taught him this, as well.

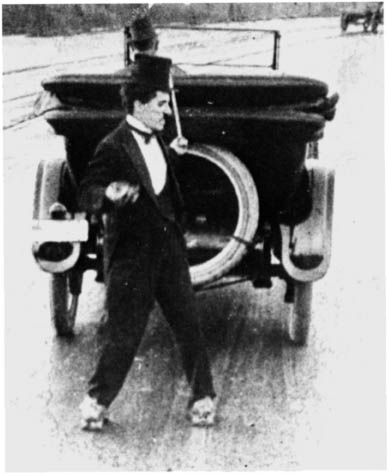

Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (1936).

Out of the three silent comic inspirations, Keaton is the closest to Chan in many ways. Keaton’s early life eerily echoes Chan’s: He started applying makeup by the age of five, and he was coming up with his own comic material by the age of eleven. His schoolmaster would throw him around on stage, even to the point of creating controversy that he was being abused. In Chan’s childhood, you could trade Master Yu for Keaton’s father. As opposed to the reclusive Chaplin, who would run to his trailer between takes, Keaton was just another part of the crew—as Chan is today. Chan’s longtime friend Tai Po remembers, “We would eat together, shower together, go out together and sleep together under the same tent.” Keaton was a superb athlete, and when he and his colleagues couldn’t find a way to keep a gag going, they would often break out into a game of baseball right there on the set, throwing ideas back and forth with the ball. Chan doesn’t come up with every idea in his films; he acts as a catalyst for the collective to keep a constant flow of brainstorming alive at all times.

On-screen, Keaton, like Chan, played a variety of characters on the outside, but all had similar qualities inside. Keaton’s character was also a common man, but his face was completely devoid of emotion—yet his eyes represented the mind’s relationship with the body whether in rest or in motion. “The Keaton body in motion is equally elegant, poised, and commanding in its apparent ability to accomplish anything with the greatest ease and smoothness. Keaton performing a stunt was apparently no more taxed than Keaton at rest. . . . Keaton makes the most impossible physical stunts look as difficult as nonchalant, everyday activities,” wrote Gerald Mast in his analysis of Keaton’s work in The Comic Mind.

Buster Keaton in The Navigator (1924). (Kino Video)

In 1920 Keaton set up a great gag in one of his two-reelers (shorter films made up of situations or gags) called One Week. The facade of his house is falling down around him—but he’s unscathed because of an open doorway. In Dragon Lord during a Chan fight with two guys in a theater, a platform falls in a similar fashion, with Chan left standing in a space in the platform. In Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), Keaton expands on his gag by having an even larger house facade fall around him. Chan also upgrades the gag in the finale of Project A II (1987).

Keaton in The Love Nest. (The Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive)

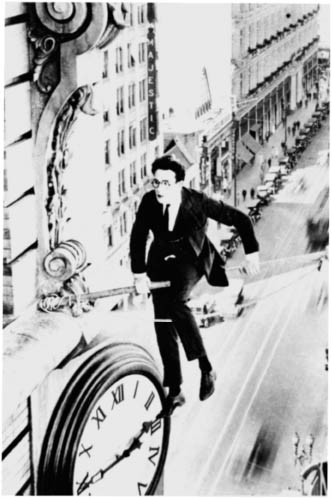

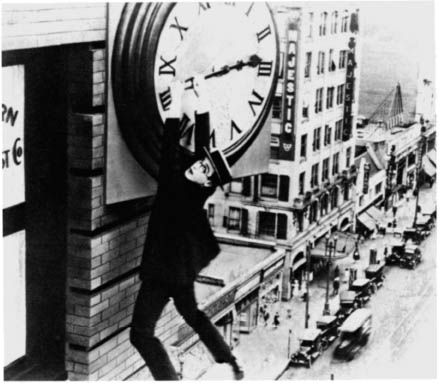

Harold Lloyd in Safety Last (1923).

In every Jackie Chan film, there is a trademark move that embraces Keaton’s theory, which is to have completely outlandish action using no camera tricks, showing the audience that it is entirely possible in real life. In Project A Chan scurries up a wall of bricks; in Armour of God II he kicks off of a wall, propelling himself to catch the bottom of a small bridge; and in Rumble in the Bronx, he makes a few small jumps to get over the top of a gigantic fence. “I watched him run up that fence as if he was a cat,” marveled Mark Akerstream, assistant stunt coordinator, who played the character Tony in Rumble in the Bronx. Similar moves can be found in all of Chan’s best films.

While Keaton and Chan are very similar in real life, and Chan pulls most of his physical abilities from him, it is with Harold Lloyd that Chan shares an almost identical on-screen characterization. Harold Lloyd was the common man who didn’t cling to daydreams like Keaton or fancy himself a cute tramp like Chaplin. With his average looks, tall, thin shape, and round-rimmed glasses, Lloyd seemed like any other man on the street, playing characters like a husband, a store clerk, and a doctor. “Lloyd’s ‘character’ was pure literature,” explained critic Gerald Mast. “Harold is the affable boy next door, anxious to get ahead, not very good at anything, but willing to compensate with energy for his lack of talent. He is the American Dream of what a mediocre man can accomplish with a lot of hard work.” Lloyd takes many great risks in his films, but unlike with Keaton, the audience can see the anguish on his face because he isn’t a man of action but a man at risk. Chan takes a balance between the two, but he clearly assumes much of the motivations of Lloyd’s characters in his films.

Lloyd—ordinary man in an extraordinary position.

Chaplin’s antics in “The Rink” are echoed in Chan’s bus stunt in Police Story decades later. (The Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive)

Chan’s silent comedian tribute in Police Story. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan obviously borrows and expands on Lloyd’s classic building ascent in Safety Last (1923) for his famous clock tower sequence in Project A. In the Lloyd movie, the climb was to have been performed by an athletic friend—Lloyd’s idea being to attract a crowd around the department store he worked at. When it comes time for the climb, with the crowd waiting patiently, Lloyd must do the climb himself, motivated by both his friend’s disposition and his own, in this case getting him further in the workplace. Mast noted: “Whereas Keaton performs his heroic deeds simply because he must, because he can’t avoid them, Harold only does so after getting himself all steamed up.”

Criticism has been made of Chan, whose character is poked and prodded with only minor irritations but eventually explodes with a momentous climactic battle. Lloyd faced similar criticism that his films were slow-moving, with action coming only at the end. In Lloyd’s character’s mind, he needs to climb only one story but is pushed into climbing another and another and another. Chan’s characters are similarly driven. They are given what look like simple tasks, which escalate out of control, forcing Chan to come out of his shell. In Project A II Chan’s only job at first is to supervise a police district in a rough part of town. While he is pulled away from his vacation and subsequent retirement from the force in Police Story II, Chan is just asked to assist an investigation involving a series of bombings. All Chan has to do is ride in an airplane to keep tabs on a suspect in First Strike. In all three scenarios, when things get serious, Chan’s inner strength takes over his initial playfulness to perpetuate the action.

Charlie Chaplin’s inspiration can be noted in many of Chan’s gags used for comic effect although they have no bearing on the plots themselves. Chaplin’s films were lessons in social commentary, bringing controversial political themes to light. While Chan wouldn’t dare use such devices to “spoil the fun,” he does, however, use Chaplin’s rhythmic timing in relation to subtle gags. Chaplin would orchestrate how he wanted music to be used with his movements. Chaplin’s most famous gag was in The Gold Rush (1925), where he uses two forks stuck in two bread rolls to pull off a little dance. Chaplin’s inspiration can be found in Police Story, where Chan on desk duty comically juggles various phones, mixing up severe calls with inconsequential ones. Chaplin can be found in the smallest, most unimportant moments in Chan’s films, say, when Chan throws a hat from behind that lands perfectly on a hat rack in Mr. Canton and Lady Rose. As for the source of the props that Chan brings into his fight scenes, Chaplin can also be called the usual suspect. By using the best from all three silent film greats, Chan is able to fuse his ideas and Edward Tang’s foundation to create a solid, if formulaic, character that the audience never grows tired of watching.

Edward Tang King-sang is the writing force behind Chan’s greatest films: the first three Police Storys, both Project As, both Armour of Gods, Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, and even Chan’s first two period films for Golden Harvest, Young Master and Dragon Lord. Ever since Golden Harvest assigned him to work with Chan on Young Master, Tang knew that he was working with someone special. He has been with Chan ever since.

Chan’s Chaplinesque phone juggling in Police Story, as depicted in a Hong Kong newspaper ad for the film. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Tang read several Chinese folklore books to pull out heroic elements to develop Chan’s character. “When something bad happens, everyone wishes that a hero would come out of nowhere and save the day.” One of these books is Cea Deu Ying Hung Jeung, otherwise known as Eagles Shooting Heroes. The book was written in the 1950s by one of the most prolific Chinese writers of the modern day, Louis Cha, who serves as the head of Hong Kong’s largest newspaper, the Ming Bao. The novel is set during the Sung Dynasty, centuries before the Ching Dynasty settings of most kung fu films. The novel uses allegorical archetypes of morality and spirit as characters. The storyline is an intricate web of relationships that manage to trap all of these characters at different points in time, not exactly affirming any one particular setting.

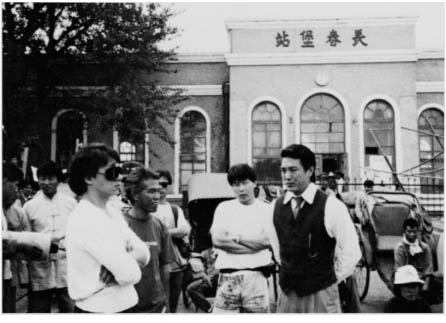

On the Drunken Master II set (left to right): Chan, Edward Tang, unidentified, Kenneth Low. (Courtesy of Edward Tang)

In 1993 a film parody of the book, Dong Cheng Xi Jiu (Eagles Shooting Heroes in English), was released, with lukewarm results despite the impressive cast. For non-Asian audiences it’s difficult to find any semblance of the Jackie Chan character inside of this structure since the Chinese plotline would be too difficult to understand. Just one year later, art house director Wong Kar-wai released Ashes of Time, an over-stylized, tremendously convoluted, revisionist prequel to Cha’s story.

Most of what Tang saw in the Cha book relates to Chan’s fighting abilities. “During the Ching Dynasty, everyone fought with swords, but the protagonist in the book many times used his bare hands as weapons.” Since the book had a great deal to do with wu xia pian (fantasy swordplay), the relationships, both romantic and melodramatic, were a necessity. “That’s because, unlike the Mandarin fight flicks that introduced Hong Kong movies to the West, the [Cantonese] genre’s primary audience was women,” explained Sam Ho in his analysis of the book. The majority of action films are oriented toward men while Chan’s films are made for the entire world. Tang has shaped Chan’s heroic character by scripting most of the films himself. “At first, I write the entire script scene for scene. After Jackie sees it, he makes suggestions, after which I rewrite the scenes accordingly.” In a nutshell, Tang comes up with the premise, Chan puts his spin on it, and Tang follows up by keeping a flow of continuity.

In 1960 Siegfried Kracauer came up with a radical view of what non-story films were all about. He called them “experimental films,” stating the notion that “storytelling interferes with the cinematic approach.” True, the masters of the cinematic technique—Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, and more recently David Lynch and Wong Kar-wai—use sound, vivid images, and symbols to tell their stories.

In the case of Jackie Chan, Kracauer would most likely say that storytelling interferes with Chan’s approach. Chan’s films are not about stories—they are about him. Similarly, in Hollywood, Jim Carrey’s brand of manic comedy is all that is needed to make his films work. Once a plot is introduced, as in The Cable Guy (1996), the result is lukewarm compared to the way Carrey’s films should operate. As Chan says, “Even now, they [Asian audience] are not interested in my story. They come to the theater and the most important thing is that they see Jackie Chan. First, it’s Jackie Chan, then Jackie Chan’s action, then Jackie Chan’s comedy, and then, Jackie Chan’s dangerous stunts. All those never change, but the audience doesn’t change—I change myself.”

The Jackie Chan genre can never have a story that eclipses the star. This is possibly why many people were turned off with Stanley Tong’s First Strike, where Chan was putting his spin on James Bond. James Bond, as everyone knows, has to save the world. A conflict of this magnitude has become the plot point for so many action adventure films that the audience expects it. Chan’s conflicts, at least the ones that he is control of, are a lot more personal and smaller in scale. The one essential ingredient in Chan’s plotlines is the conflict that puts his character in a neutral zone, a place that lies somewhere close to the good but not too far from the bad. “Jackie always believes that there is good in bad, and vice versa,” says Edward Tang. In all of Chan’s genre films, this is the conflict that breathes life into Chan’s underdog characters.

This modus operandi’s defining moment comes in the form of Project A. After Chan and company enter a fancy club that is harboring members of a gang, the entire place explodes with fight action as the criminals are revealed. The club’s owner, a prominent businessman who wields great power over the police, coerces the police captain to put an end to the commotion. The police captain intervenes and not only orders Chan and his men to stop fighting but forces Chan to apologize for wrecking the place. Disgusted, Chan says, “I quit! So be it.” He throws down his badge and tells the captain to pick it up. Chan was provoked into fighting for justice in the first place, and it looks as if he is leaving the gangster he sought behind, safe upstairs. Chan looks at the ground for a moment (showing those Keaton wheels turning), then finishes what he started by leaping upstairs to bring the criminals to justice.

When Chan is pushed too far, he must find it in himself to overcome the odds. Chan’s genre films all contain this underlying factor in varying degrees. In Police Story he is framed for the murder of a cop and to prove his innocence he must take his superior hostage. In Project A II he is framed for stealing from a rich family that he is supposed to be protecting. In Drunken Master II he is found inside the British Consulate, whose officials trade his freedom for the land on which his father’s medicine practice sits. In First Strike he is suspected of killing a Chinese mafia leader. Being stuck between a rock and a hard place creates the pressure necessary for Chan to perform his manic moves to save himself and overcome the conflict at hand.

Villains have always made for great characters, but they, too, have been stereotyped into repeating the same lines over and over again. Part of the surprise in Chan’s films is the ominous forces that he must do battle with in order to save the day. While hints of an antagonist’s character and actions are speckled throughout each film, the audience is kept from knowing how the finale will finally unfold. This started in Dragon Lord, where Chan added the glass eye to Whang’s character, not letting the audience see it, due to various obstacles, until the very end. Who would have expected that Chan would have to fight four Amazons in Armour of God or get whipped by a deaf martial artist in Police Story II?

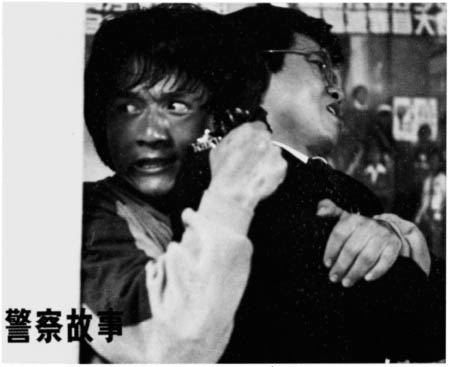

The modern world is the setting in many of Chan’s genre films, but only a film microcosm of the modern world, allowing Chan to work within his means without the limitations of reality. Thus, guns are used only as signs to begin conflict or accent danger. They are even used as gags, but rarely will they be used as in a gunfight, because this isn’t Chan’s type of action. The finale of Police Story, set in a mall, has countless bad guys fighting with Chan, but guns are nowhere in sight. A gunfight would be too simplistic for Chan’s talents.

The mise-en-scène is one of the most important elements of Chan’s version of the modern world. This film term describes the physical factors used in a setting, such as lighting, props, and costumes. Chan is the auteur at using mise-en-scène to his best advantage. His team of stuntmen spend hours on end in arranging props to make the setting an able member in the fight. Large set pieces are part of the settings as well, further proving that Chan’s films are part of an escapist world. In Armour of God II, a gigantic wind tunnel allows Chan and his foes to fly around like Superman, adding flavor to their bout. The end fight in Mr. Canton and Lady Rose is situated inside of a gigantic rope factory, all of its details adding danger and excitement. A large aquarium provides First Strike with its twenty-minute underwater battle, featuring armed scuba divers and maneating sharks. The finale in Mr. Nice Guy takes place on a construction site, where a buzz saw and a concrete mixer enliven the action. Chan’s set pieces are wildly inventive, too choreographed to be taken seriously, and they must be accepted on such a level. Given Chan’s comic approach to the whole matter, these modern settings are perfect complements.

Chan takes his superior hostage in Police Story. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

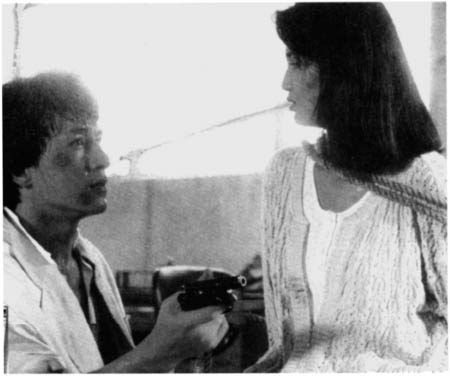

Chan rescues Maggie Cheung in Police Story II, one of the few Chan films to develop a romantic relationship. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan’s films are also very generalized in terms of sticking to a linear narrative. One won’t see flashbacks or flash forwards, which might confuse his general audience. With films kept simple, the translation can’t possibly lose the viewer, despite inaccuracies in dubbing and subtitling. Chan evokes a sense that he is Chinese, but he doesn’t bring in too many Asian cultural ideals into his pictures. He knows that his international audience will not fully understand Chinese cultural humor or customs. If there is a mention of them, he will try to explain them.

Notice that Chan’s relationships in his films are tied to the conflict, not necessarily to other characters for their sake. One won’t see long romantic scenes or sex scenes. In Armour of God when one female character tries to kiss him, he laughs in her face. In Supercop Chan’s girlfriend tries to get closer to him, but he topples off the bed reaching for something underneath. As the underdog, Chan denies himself the opportunities to have on-screen romances. Police Story II is the only film that really tries to tie in Chan’s relationship with his girlfriend, played by Maggie Cheung. In one dramatic moment, the bad guys read the girlfriend’s heartfelt farewell letter to Chan while both Chan and Cheung are tied up facing each other. But scenes like this are few.

In Armour of God II Chan has his choice of Chinese, Japanese, and European women. Chan makes light of this in a fantastic gag where the four are held by two bandits in the desert with apparently no water. Chan, however, has a hidden pouch of water around his waist, with a small tube running up toward his face. He nonchalantly rubs up against each girl, and before she can scream out in disapproval, the sight of water has her wrapping her legs around him in satisfaction—as their misunderstanding captors watch in amazement.

Chan also stays clear of controversy, although Armour of God comes close with its treacherous monks who aren’t monks. “Originally, we created this war between the Catholics and the Islams,” said Edward Tang, “but we had to keep things very ambiguous since religion is a sensitive subject. We never reveal any of the religions in the films.”

The Jackie Chan genre also contains a few fixed aspects that are inherent only to Chan’s style of filmmaking. When Chan performed the clock tower fall in Project A, he did it not only once or twice but three times. The stunt is so amazing that he puts on film all three of his attempts back to back. Chan does the same thing with his fall in Police Story, as well as stunts in all of his modern films. It is common for a filmmaker to repeat a clip of a particularly interesting move, but when Chan shows a different angle or another attempt entirely, he is breaking the temporal plane in which the action rests. In a sense Chan is creating his own documents to his physical abilities.

In all of his directed features, Chan uses the scope format (aspect ratio 2.35:1), but not just because of his filmmaker’s preference. The Shaw Brothers used this format (dubbed “Shaw Scope”) for their kung fu films in the late sixties and seventies. This format gives the audience a complete view of the actor performing—there’s little room for the director or anyone else to cheat. When Chan took the helm, he learned to command the wide screen as masterfully as Sergio Leone did with his “Man with No Name” spaghetti westerns. Chan has a knack for filling up the screen with action on the far left, the far right, and the middle simultaneously. Three of Chan’s best films—both Project A’s and Mr. Canton and Lady Rose—almost look like substandard efforts if they are not shown in the correct aspect ratio. This aspect ratio can be seen on home videotape only in the letterbox format, where the horizontal is two and a half times as long as the vertical, the excess screen being blacked out. With wide-screen–angle lenses, another component of Keaton’s filmmaking, it’s difficult for Chan to cheat by exaggerating his physical abilities since all of the room around him is completely exposed. Tight shots are used only for basic dialogue sequences, while the majority of the action is kept in wide angles with the camera completely still. The intensity of the scene rests on the actors’ abilities and not necessarily the editing.

The final element that makes all of Chan’s films unique is his personal singing of the theme songs at either the beginning or the end. Like the bard who poetically chants of his amazing travels, Chan’s theme songs are melodic leitmotifs of being that “unsung” hero. If he isn’t going to sing about heroes, he sings about love in his ballads. Chan can sing in Cantonese and Mandarin, actually preferring the latter because he likes the flow of the language. (See the lyrics below.)

An interesting departure from his normal hero theme is in Drunken Master II. Here he relishes his drinking abilities, but the song is meant in good fun. After all, the film is a comedy, and he surely isn’t trying to give kids the wrong idea about alcohol. The original theme song for Hwang Fei-hung in the now-famous Once Upon a Time in China series takes a different approach to the character—making him valiant and stoic. Coincidentally, Chan sung the second film’s theme. Below is the first stanza from Hwang’s more valiant portrayal from that series, followed by Chan’s take.

Chan’s most popular theme—the one in Police Story, used in parts one, two, and four (First Strike)—is followed by the theme for Thunderbolt, although his hero in that film was a little more rigid than usual. This is a rare opportunity to see what Chan is actually singing about, because the songs are usually not translated on film for his non-Asian audiences.

Armour of God’s murderous monks had little to do with religion. Here, Chan and his buddy Alan Tam try to infiltrate their ranks. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The Out-takes

The out-takes that run during the end credits of a Jackie Chan film have taken a life of their own—and they are another way he documents his physical abilities. Certainly they are one part of his films that everyone talks about, and it’s easy to see why. Chan included random shots during the credits of Young Master, but after his experience with Hal Needham and the Cannonball Run films, the nature of the out-takes changed. Needham would always have a running credit reel (even extending past the credits) to show off Burt Reynolds and company’s botched oneliners. While Needham and Chan never discussed the use of out-takes, it’s clear that Chan sensed the crowd’s enjoyment in watching them. For Dragon Lord’s end credits, Chan inserted scenes from the film with shots of mishaps on the set. By the time Project A came around, he could cover the entire credit sequence with nothing but out-takes. Chan’s audiences let loose a continuous stream of “ooh”s and “aah”s as Chan is pummeled shot after shot. Now the audience expects to see this show of resilience and courage. Chan takes it all in good fun—singing in the background almost as if he were a wartorn soldier recounting his battle wounds. And that’s exactly what they are.

Chan wants the audience to see his anguish, his blood, his labors—because he is doing all of this for them. During the credit reel for Armour of God, ambulance sirens replace the theme song as the accident that nearly cost him his life unreels. In Drunken Master II, when Chan leaps up after having his bottom raked across the coals, the audience can see the pain and agony as he wipes his face with a wet towel. His costars fare much the same: in Police Story II Maggie Cheung gets the top of her scalp ripped off from a falling metal frame. For the Japanese market, even Chan’s collaborations with Sammo Hung are given these amazing credit reels as testaments of his willingness to please the audience at any cost. As Chan’s films get more and more overblown in magnitude, the audience eagerly waits for the next dangerous display of real-life action. Never leave a Jackie Chan movie until all of the credits have appeared or, better yet, until the screen goes black.

“Once Upon a Time in China Theme” (first stanza only)

Facing the challenge with great confidence, I see blood spraying like the red sunshine.

I am fearless, courageous. I got the body of steel.

I do what no one can do, and I see what no one can see.

I fight for my life, I struggle to be a man.

To be a man, you got to be stronger day by day.

“Drunken Master II Theme”

I’m bumping up and down, seems like I would fall.

Laughing is my answer toward all the pain and sadness.

I go low and I go high.

I am swaying back and forth, but I never fall,

because I know all there is to know about the art of drinking.

Fighting for fame, I never use a blade.

Carrying all the weight on my own shoulders.

I never beg and never plead, to anyone or anything.

But I don’t mind giving in to passion and honor,

As the god of drunkenness, I’m a great man.

Don’t call me crazy, ’cause a crazy man like me has a warm heart.

Don’t call at me silly, ’cause silly man with a loyal heart is hard to find.

Don’t be afraid of drunkenness, drunken as I am brings my mind to the heavens.

So go ahead, be crazy, be silly, and be drunken while you are young.

(REPEAT)

“Police Story Theme”

Feeling and tears, honor and pride, I just never care.

Heroic and fearless, I’ve been in a dangerous chase.

Live or die, I face everything with confidence.

Strong and alone, I’m always out there to do my job.

No matter where I am, I’ll get that job done.

While lost on the road,

I think about home with the beat of my heart.

Flowing blood, running tears, I just never care.

Heroic men only believe in truth and spirit.

No matter where I am,

I must finish the job that God assigns me.

While lost on the road,

I got to keep my spirits up.

“Thunderbolt Theme”

Probably because this world needs a hero,

Some yearn to get heroic for a moment.

Some want to show off, others prefer to be laymen.

Which type are you?

Everybody has his own dreams,

And can succeed.

You have your glory,

Yet you needn’t cause the world a sensation.

You have your glory,

Even if you’re a moment’s hero

You’re reconciled to it,

Whatever you do or wherever you go.

(REPEAT)