Rumble in the Bronx. (New Line Cinema)

The two films that depart from the Jackie Chan genre in many respects are naturally the two films where divided control played a confounding factor. In Armour of God Eric Tsang was the original director and scriptwriter. After Tsang had spent over two thirds of the budget on one third of the film, Chan took over (once he recovered from his accident). Chan had ultimate control over the sequel (Frankie Chan and Johnny To were called in to assist), but by the time the film was over, he was frustrated by the multitudes of problems. It was time for Chan to give the directing torch to someone else. He needed a break from the headaches of planning, calling all the shots, and simply waiting around all the time. Chan needed a fresh approach.

What he got was Stanley Tong, a former stuntman who had only a few credits under his belt. Tong would eventually do for Jackie what he couldn’t do himself: make an American film the Chinese way. Stanley Tong Kwai-lai was born the same day as Jackie Chan, only six years later. Compared with Hong Kong’s New Wave directors, like John Woo and Tsui Hark, Tong’s only noticeable similarity was his having studied abroad—in Canada. In his heart, however, Tong was a gutsy Hong Kongie with a vivid childhood. Like many Asian children growing up, Tong became a fan of Bruce Lee, and Chan later on. By the age of twelve, Tong developed an interest in martial arts. He studied Hung Bao boxing, tiger claw, tai chi, freestyle kickboxing, gymnastics, track and field, and swimming. But Tong was not into filmmaking; he was a student, and had dreams of going to college to earn a degree in civil engineering. As luck would have it, on a trip to Hong Kong in 1980, Tong ran into his brother-in-law, who was none other than Lo Lieh, one of the Shaw Brothers’ most respected actors. Incidentally, it was Lo Lieh’s film Five Fingers of Death (1973) that became the first Hong Kong martial arts film to receive widespread release in America. Entranced by the excitement on one of the Shaw Brothers sets, Tong vied for a chance to work in the cinema, something his parents were entirely against.

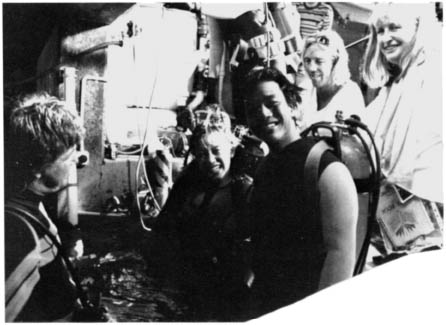

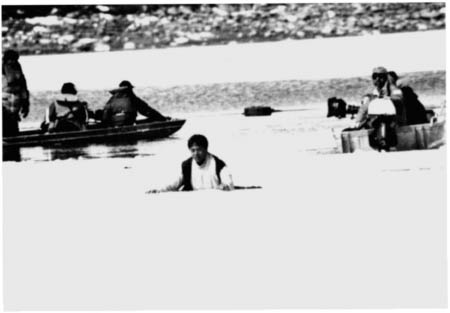

Stanley Tong preparing to shoot First Strike’s underwater fight scene. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

Through Lo, Tong met Lau Karleung, who gave him his start as a stuntman—for women, mostly, because of his size. After three years of enduring such injuries as a broken shoulder and leg, damaged knees, cracked ribs and skull, and many back-related problems, Tong made the less dangerous move to filmmaker. Cutting his salary almost in half, Tong began learning different filming techniques, as well as—sticking close to his knowledge of martial arts—learning how to choreograph stunts and fight sequences. Tong worked under John Woo doubled for Brandon Lee on his only Hong Kong film, Legacy of Rage, and finally moved up to assistant director on several small films, including Angel (1987). After handling the fight choreography on Angel 2 (1989), Tong got the chance to direct as well as choreograph Angel 3 (1990).

That same year he formed Golden Gate Productions to gain more control over his work. On a measly budget of $1.1 million, Tong wrote, directed, stunt-directed, and produced Stone Age Warriors, the first film ever to be shot in New Guinea. With lavish locations, komodo dragons, and an end fight sequence where Tong used over 1,000 New Guinea natives, this was not just another local production. In looking for a director to work with Chan, producer Leonard Ho noticed the film and showed it to Chan as well as several other Golden Harvest executives. Pleased, Chan noted the similarities between Tong’s style and his own and gave Tong the green light.

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Except for his field experience, Tong was not a typical filmmaker. He drew much of his film education from reading books, most notably Industrial Light and Magic—The Art of Special Effects, and watching “making of” videos of films like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Star Wars. Tong’s style is very Westernized, but not the overstylized, aberrant music-video style that has hampered so many action films of late.

Michelle Yeoh. (Dimension)

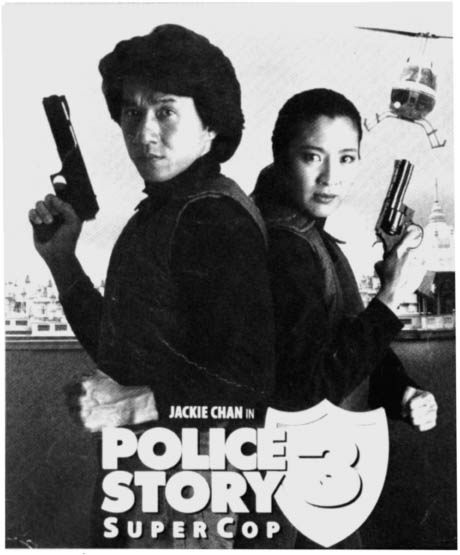

In settling the final details, Tong’s first project with Chan would be the third sequel in the Police Story series, adding pressure to create something that could topple two of Chan’s greatest achievements. Since it was a Jackie Chan film, Golden Harvest added even more sweat to Tong’s brow by giving him an unlimited budget. Everything would rest on his abilities, and even Jackie Chan was willing to give young Tong his shot. Tong described Chan’s support in a recent interview: “The first day of shooting, he [Chan] looked over my shoulder and said, ‘Stanley, you don’t have to worry because during the shooting I will give you lots of suggestions, but at the end of the day, you are the director. If you want to listen to me, I don’t need you to direct me because I have so many second unit directors who have been working with me all of these years. I don’t need that. What I want to see with the amount of money and support that I give you, is how much you can make out of it yourself. How many new things can you put into my movie? So, if I see something is wrong, I will help you, but really, you are on your own. You make the decision, because I see that you use storyboards and shot leads; you are more like a New Wave filmmaker. I know if I change one of your ideas, it could mess up your whole shoot.’ ”

Indeed, Tong had something to offer that Chan could never bring to his own films: structure. A Jackie Chan film, as mentioned before, is an exercise in brainstorming. Ideas keep developing and developing until they form gags, and those gags in turn form scenes. Tong had storyboards, though, so Chan could see that he had a game plan from the get-go, and Chan wasn’t about to second-guess someone who was “that prepared.” Right off the bat, Tong took Edward Tang’s script and rewrote over 80% of it. The original story took place entirely in Hong Kong and revolved around gangland activity in the Central District. Like the film’s predecessors, the story focused on Chan’s confidence in himself to thwart the villains, whose particular crime was robbing jewelry stores. In changing the script, Tong did leave in Maggie Cheung’s recurring character as Chan’s feminine balance.

Michelle Yeoh in Supercop. (Dimension, Media Asia Group, © STAR TV))

He also added another female character in the form of Michelle Yeoh Choo-Kheng. Also known as Michelle Khan, Yeoh was Hong Kong’s top female action star, setting off the entire 1980s femme fatale action craze with Yes Madam (1985) for the newly established D & B Films. Having studied ballet at the Royal Academy of Dance in London, Yeoh made the jump into films due to a knee injury that prevented her from dancing anymore. After she appeared in the Sammo Hung film Owl vs. Dumbo (1984), Hung’s team, Lam Ching-ying in particular, began teaching her martial arts in preparation for her action heroine status. After her Yes Madam success, Yeoh made several other action films during the mid-eighties, but dropped completely out of sight when she married Dickson Poon, founder of D & B Films.

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Luckily, the film she dropped out of, Magnificent Warriors, was one of Tong’s final stunt-doubling jobs. Tong remembers his first experience with Yeoh vividly, as told to Colin Geddes. “I was putting wires on her body for a stunt, and I was being very quiet. All of the sudden when fixing her back, she turned around with a strict face and said, ‘Stop pinching my bum!’ Everybody in the room—the stunt coordinator, some actresses, the makeup ladies—they all just looked at me with big eyes. My whole face went red, and I said, ‘No, I didn’t do it!’ ‘What are you talking about?’ she said. ‘Just don’t do it anymore!’

“The stunt coordinator rushed over and asked, ‘What happened? Stan, what did you do?’ I said, ‘I didn’t do anything!’ She burst out laughing and said I didn’t do anything, and that I was just too quiet and she wanted to break the ice!” The two quickly became friends, and when she married, she asked Tong to keep training her as a hobby. Yeoh was given more formalized martial arts training as well as lessons in tumbling, and weapons, including the staff.

“I told her that if I ever did become a director, that I would love to work with her.” Tong thought that it was a great gimmick to bring the number-one male action star together with the number-one female action star back out of retirement. It was just a coincidence that Yeoh had divorced Poon. When she saw the script, Yeoh immediately accepted it, making this her third experience with Chan. Early in her career, she worked with Chan in a commercial, and in 1985 she played a judo instructor in the film Twinkle, Twinkle Lucky Stars. Although she didn’t appear on-screen with Chan, she fought Sammo Hung during the dojo sequence.

Tong brought an international flavor to the third Police Story by shooting the film not only in Hong Kong but also in Mainland China and Malaysia, particularly its capital, Kuala Lumpur (Yeoh, born in Malaysia, won the Miss Malaysia Beauty Pageant in 1983). The final touch of Westernizing Chan was the use of synch-sound. Though the film was mainly shot in Cantonese, synch-sound put the reality back, something that Tong felt had hurt the Hong Kong film industry as a whole. Everyone was against it at first, noting that Chan’s films were always dubbed in Mandarin and English anyway, but Tong stuck to his guns and made a synch-sound Jackie Chan film. Tong was in complete control of Police Story III: Supercop—even taking over the stunt directing from Chan. The final cost was a remarkable $10 million.

In terms of plotting, it was back to a familiar old enemy: the kingpin drug smuggler, but the scenery was new, which challenges Chan’s character. Kau Kui (Chan) no longer fights his battles in familiar Hong Kong but abroad, making him the underdog again. Chan’s loose-cannon cop is tricked into taking on a major undercover assignment: to get close to a drug lord whose activities account for one third of the drug trade in Southeast Asia. Aiding him on his quest is Bill Tung, who plays his police superior uncle, and a mainland Chinese cop—Michelle Yeoh—who introduces another new element.

In his previous “buddy” films, Chan really remained the star, but since Tong was running the show on Police Story III, Yeoh would be the balance that Chan could not topple. She matched Chan’s yin with a perfect yang—Inspector Yang, that is. Hong Kong’s culture is unscathed by politics and derived from the hearts of the people who live there. In contrast, Mainland Chinese are disciplined, with less freedom to do as they please. Hong Kong’s happy-go-lucky Chan and Mainland’s by-the-book Yang made for great complements, and this strength makes Supercop a winner in the end.

Though Chan admits that it was not intended, Yeoh actually outshines Chan in several scenes and even fights more than he does when put to the test. Who would have thought that a female counterpart to Jackie Chan would draw more attention than the man himself? Tong exhausts all of the possibilities with their characters, especially when the two must both go undercover together as brother and sister. To add to the chemistry between Chan and Yeoh, Maggie Cheung returns as Chan’s longtime girlfriend, managing to shake things up quite a bit, even exposing their little charade. The comedy works so well that one almost forgets that it’s an action film.

Yeoh did all of her own stunts in Supercop, such as falling off of a moving car and performing that amazing jump onto the train via motorcycle. She learned how to use the motorcycle along with Tong just days before the actual jump took place. After a stuntman broke his leg attempting it, Yeoh did it perfectly the first time out.

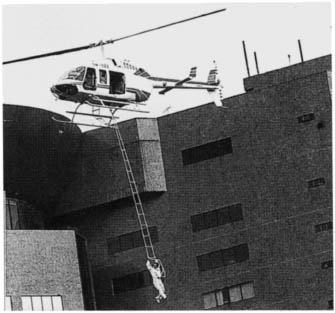

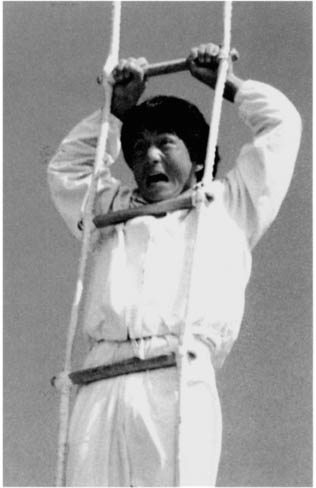

Of course, Chan had to better this stunt by hanging from a rope ladder connected to a helicopter. His jump to the ladder was death-defying due to the fact that an airbag was not used 100 feet below. Government restrictions to the locations and other logistical problems allowed only a bunch of empty crates and some plastic sheets to break any fall. In the seven-minute sequence, Chan (harnessed by two wires to the ladder itself) takes a high-speed flight through the city of Kuala Lumpur without a blue screen or computer effects to enhance the effect.

After the helicopter flight, Chan and Yeoh must subdue the enemy on top of a train. One of the most impressive fight gags was to have Chan kicked off the train, only to grab onto the mail carrier, swing back behind his enemy, and surprise him. Stuntman Alan Sit Chun-wai, who operated the helicopter in the film, notes the accident that followed. “Chan was harnessed to the carrier with two hooks. For the stunt, he was supposed to unhook both of them at the same time, but he could only get one.” Chan’s films always have “great misses,” but, unfortunately, the nose of the helicopter plowed right into his back, knocking him briefly unconscious.

The third Police Story outing created two factions of fans. Hong Kong fans familiar with Chan criticized the film since it lacked the intensity of his two previous efforts. True, none of the action scenes in the film were examples of Chan’s outrageous use of physical abilities—no Buster Keaton influences and no fifteen-minute fight finales. Tong’s style was to build larger stunt sequences, using his expert use of wide angles to capture the realism. The film easily looks to have a budget three times of what it was made for, and the variety of action has merit since most of Chan’s sequences are fight-based.

(Courtesy of Edward Tang, Media Asia Group, © STAR TV)

Still, the first two Police Story films painted a different Chan character from even his other films. Perhaps inspired by his harder-edged character from Heart of Dragon, Chan’s Kau Kui was a simple working man who went into an almost animalistic rage when faced with danger. He was a firm fighter, even willing to throw the first punch without hesitation. In Supercop, however, Chan’s character is definitely a tamer version.

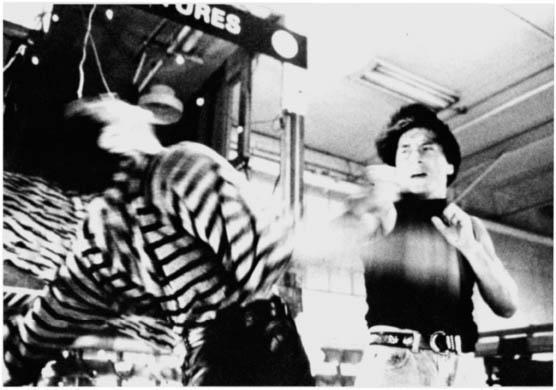

Chan in the first store brawl of Rumble in the Bronx. (New Line Cinema)

Even more disappointing is what the film does with this great character called Panther, played by Chan’s Peking Opera brother Yuen Wah, who played the bad guy in Dragons Forever as well as in many other Hong Kong action films. If anyone was to be the ultimate villain for Chan, it would have been Yuen Wah. After several scenes between the two, and Yuen getting in some pretty good punches, he just gets kicked off the building—a pretty anticlimactic demise. Tong felt that Yuen was just not up to snuff compared to Chan, so he used Kenneth Low Houi-kang (Chan’s real-life bodyguard) and Wong Tsi as bad guys to do the real dirty work on top of the train. The film did manage to cast one veteran villain, Tong using brother-in-law Lo Lieh as the Thai general hiding under those dark sunglasses.

Supercop became an international hit, despite being clobbered on its own home turf by the comedic antics of Stephen Chiau Sing-chi, whose films cost one third of Chan’s. Chan went on to win Best Actor at the Hong Kong Film Awards for his new portrayal of Kau Kui. The glossy look, matched by the stunning locales and complex stuntwork, strengthened Tong’s position with Chan, who wanted Tong to direct two more films and a project of his own. And Supercop made Michelle Yeoh the highest paid, most sought-after actress in Hong Kong cinema. What it didn’t do for Hong Kong audiences, it did do for everyone else. If Chan’s career was to ever reach the apex of true international acclaim, Tong was to be his ticket to get there.

The next year Tong directed a semisequel to Supercop entitled Project S (a.k.a. Once a Cop), concentrating on Yeoh’s character. On a budget of only $3 million, Tong was able to make it look just as fresh and exciting as Supercop. He originally planned on shooting the film in India and Japan but bowed out after a riot erupted in India, forcing him to shoot closer to home. Tong was able to experiment with models and other types of special effects, finally putting what he had learned from the books to good use.

The Project S plot borrowed most of the original script idea of Supercop. Yeoh is sent to Hong Kong to take down a gang bent on robbing the Central District’s main bank. The only problem is that the gang leader is her former boyfriend, who left China only a few years earlier. Tong’s attention to their relationship is handled with the utmost of care, and the villains are more colorful than in the usual Hong Kong flick.

Chan made a cameo appearance, a free favor to Tong, as his Police Story character dressed in drag, fighting a couple of thugs who try to rob a jewelry store. The action sequences are top-notch, including an incredible jump off of a building at the beginning and a fight between Yeoh and a seven-foot adversary at the end. Fans of Supercop will not be disappointed with its smaller, more personal companion.

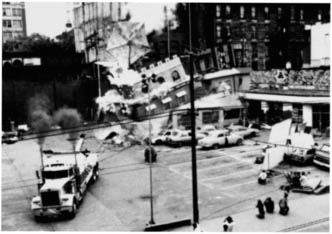

Originally set to mastermind the executive producer duties on Drunken Master II, Tong would next collaborate with Chan by directing Rumble in the Bronx instead. For virtually the same reasons that Supercop got mixed reviews, Rumble was just the opposite. In lieu of a coherent plotline and developed characters, Rumble did have the manic Chan action scenes that his fans expect. It had one universal element of Tong’s films, the story of a fish out of water, but the basic conflict of a bunch of punks who intended to wreak havoc on a Chinese-owned store seemed too straight-to-video for a $13-million production. Since Tong couldn’t afford big-name actors to play the non-Asian roles, the problems with using synch-sound are even more apparent, though dubbing would have looked worse. With Edward Tang scripting the film, it ran into a few linguistical problems: some of the lines of dialogue not sounding quite right. Rumble in the Bronx did have one thing going for it: Chan looks as if he is in urban America directed Hong Kong style, despite the obvious Vancouver settings doubling for New York. Chan’s innocent romance with the camera made it easy to overlook the plot holes, and Rumble’s comic book style was just fine.

The main problem with the story, accepting the loose structure, is the fact that there really isn’t a central villain. Chan starts off by fighting colorful street hoodlums, then all of a sudden he faces undeveloped mob characters who come out of nowhere. Chan’s typical finales are all about surprises, but they do have personal links, pitting the agitated Chan toe to toe against the nemesis whose true powers are revealed only at the film’s end. In Rumble, however, Chan actually makes amends with the dim-witted street gang leader. Then the whole subplot with the mob comes to a head with Chan tearing up the streets with a hovercraft. Action sequences are thrown at the audience in dizzying numbers, but their manifestations are derived from plot dribble. In other words, Chan’s earlier fight sequences with the gang become simplistic routines instead of building up to something more ominous.

Tong’s filmmaking style does make subtle touches of brilliance amid the script’s disorientation. Although the theme is never fully enforced, Rumble in the Bronx makes a number of allusions to the Chinese-émigré subculture in America. When Chan first comes on the screen, the camera paints the picture of an uncomfortable character who must adjust to the ways of Chinese America, personified in his uncle, played by Bill Tung, as usual. As he walks into his uncle’s apartment, Chan notices the traditional wooden martial arts dummy used in a very untraditional manner—as a hat rack. When everyone supposedly leaves the room, Chan dismantles the dummy’s camouflage and decides to get in a quick workout. With dust speckling the air, Chan blocks, punches, and kicks with animated flair, echoing the real use of the ancient contraption.

The uncle and his African-American fiancée engage in what looks like a traditional American setting for a marriage ceremony. With gospel singers in the background, the men dressed in tuxedos, and the bride in white, it looks as if Chan’s uncle has given in to American customs. After this ceremony, however, the couple is seen dressed in traditional Chinese garb, with the bride in red. The two deliver their vows with a Chinese song. Integrated marriage customs presented both ways adds the only strain of script originality. (Only the second ceremony appears in the Chinese version of Rumble, as the American version was condensed to highlight the action sequences.)

The destruction of the grocery store. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

After Chan’s first encounter with the gang, he grabs the only Chinese member and makes him apologize to the market’s new owner, played by Anita Mui Yim-fong. He spouts off his plea in English, disregarding the fact that Mui speaks very little English herself. Noting the sign of disrespect, Chan grasps the culprit with even more vigor, forcing him to repeat himself in Chinese. Only after doing so does she reciprocate with a courteous acknowledgment. Chan’s love interest in the film, Francoise Yip Fong-wah, could have been the vehicle for his character to accept the ways of this integrated culture, but she simply stays within her mold, and Chan does so within his.

The subdued comedy in the film saves its non-action ending from being a total waste. The sequence with the one-way mirror—where Chan makes heroic facial gestures, allowing Mui to laugh at him in private—is classic. But the Anglo actors tried for a broader approach to comedy, more tongue-in-cheek, and it just didn’t work.

Yet, with all of the film’s problems in terms of acting, plot and coherence, the action was the real winner, and Jackie Chan fans could rejoice knowing that it was Chan’s style of action, not necessarily Tong’s. The fight in the gang’s headquarters is classic Chan action, using all of the assorted props as active members of the scene. “Jackie would just walk around the room, and you could see the wheels turning as to what he was thinking about doing. Soon he would look at something and come up with an idea to work off of,” says Marc Akerstream, who played gangleader Tony and served as one of the film’s stunt coordinators. The scene was shot in bits and pieces over the course of fifteen days, a very short amount of time for shooting a Hong Kong fight sequence. Not all of the props were thought of before the choreography was orchestrated. Since the film was working with a limited budget, the crew had to use whatever they could get their hands on. Only after the room had been situated with pinball machines, television sets, refrigerators, and other assorted oddities did Chan begin to work his magic. “We would be shooting for hours on end, and everyone was getting restless,” remembers Akerstream. “After it looked like the scene was just about over, Jackie would think of more ideas to keep it going. One thing I learned was that a Jackie Chan fight scene isn’t over until he says it’s over.”

One of the most original, if not realistic, ideas was using a hovercraft for the film’s finale. On a trip to Queensland, a group of Golden Harvest representatives, including Tong, happened upon a small hovercraft escorting some tourists. Tong used a real hovercraft, along with a dummy constructed of a shell and a semitrailer. Tong notes that the entire hovercraft sequence was supposed to be funny, but many mainstream fans found it just too silly. Vancouver’s City Council created a problem when, on a moment’s notice, it cut the filming of the scene on the streets from twelve to nine days. Originally, Chan was supposed to have a final fight sequence on top of the hovercraft, but due to his ankle injury, an alternative plan had to be devised. “I went across the street to get a drink,” Chan recounts, “when I saw a knife shop with this big Swiss Army knife. I looked at the knife and said, ‘Ah, it makes sense!’ I can cut the air back on the hovercraft. Then I went and told Stanley, ‘Now I don’t have to fight!’ Then we came up with the car. They said Lambourghini. I said perfect!” Improvisation once again saved the day.

The most difficult stunt in Rumble in the Bronx was the jump between two buildings putting an end to the chase sequence between Chan and the gang members. It was six and a half stories to the ground, with wires, transformers, and other film equipment filling the space with even more danger. There was an air bag on the ground, but the angle of the jump and the obstacles made it useless. Men were stationed on every floor with various nets as backups. “I knew that if he didn’t make it and he hit the balcony, that he would spin upside down and crash through a couple of balconies and get tangled up in the electrical wires below. He would have been really busted up,” recalls Akerstream. A wire was considered, but then the user would have to put his faith in the equipment. Besides, to get a clean shot of the jump, it wouldn’t look right.

What happened next was something that could happen only in a Hong Kong production. To extinguish the rumors: Jackie Chan did not make the jump. Why? The complexity of the stunt itself and the impact of the landing would have been unbearable on Chan’s legs. Chan has hurt his legs, feet, ankles, and especially his knees on several occasions. It’s amazing to think that the man can still do all of the things he does and live to tell about them another day. Chan’s legs are peanut brittle, barely held together by a very thin string of operations. Chan could have easily jumped the distance, but the impact would have damaged his knees and ankles, sending him to the hospital for the umpteenth time, thus holding up the $13-million production, which was on a strict deadline. It wasn’t a chance he or the rest of the crew could take. The world’s greatest stuntman would have to yield to someone else willing to take the risk.

Chan punishes gangleader Marc Akerstream. (New Line Cinema)

The decision was made. There was one man on Akerstream’s team of Canadian stunt-men and on Tong’s team of Hong Kong stunt-men who could do it. It’s a well-known fact that Stanley Tong tries out most of the stunts before he endangers the life of any of his actors. Tong broke his ankle performing the stunt of the villain plummeting from the helicopter to the train twenty-five feet below in Supercop. He also doubled for one of the many ski attackers that chase Chan through the snow in their next collaboration, First Strike. In this case, though, it wasn’t just another actor or just another stunt. The timing had to be perfect for the stunt to work, and Tong gathered himself together and made the call to use himself. “Stanley had all these directorial things to get out of the way, logistics and such, but right up to the time of the shoot, I saw him turn from director to stuntman right before my eyes,” says Akerstream. “I was less apprehensive once I saw that transformation take place. He started to focus: ‘I’ve decided to do it, and I want you to support me.’ Of course we did, and that was that.” Tong executed the jump with perfect accuracy the first time, and that is what the audience sees in the finished cut of the film.

Why would the director get out of his chair and perform a stunt so dangerous? To understand this, one has to understand Stanley Tong. Unlike Chan, Tong is a meticulous, soft-spoken man who never stands out in the crowd. He isn’t the center of attention, and he shies away from the glitz and glamour of filmmaking. One could characterize him as a sweet, gentle person whose voice would be better suited for a profession in medicine rather than action films. Tong was even quoted as saying that he liked to spend most of his free time at karaoke clubs, sipping on tea and perhaps singing a melody. His favorite Western film is The Sound of Music!

On the set of a Hong Kong film, especially one of Chan’s, the director has to earn respect from everyone to keep some kind of control. Tong’s way of earning that respect simply brought him back to his roots as a stuntman. It wasn’t a measure to steal Chan’s fire or even flaunt his own physical dexterity. Tong merely did what he has always done. “It was the most dangerous stunt that I have ever seen anyone perform,” remarked Alan Sit, who worked as a stuntman on the film.

The greatest test of Tong’s “fish out of water” character was the third sequel to Police Story, domesticating Kau Kui even more than in Supercop. Originally, the film was called Police Story IV: Piece of Cake describing the ease of Chan’s assignment in the film, but with a title like this, would the world expect an action film? Changing the subtitle to First Strike, this would be Tong’s grand international achievement, using a detailed, cohesive story as the backdrop for Chan’s chance to play James Bond. While Supercop went back and forth between Cantonese and Mandarin, and Rumble in the Bronx had English and Cantonese, First Strike’s use of languages is even more diverse, with 50% in English, 15% in Russian, and 35% split between Cantonese and Mandarin. Instead of the comic book-like setting of Rumble, First Strike opts for realism, and the characters and locales—Australia, Moscow, Hong Kong, and the Ukraine—look as real as they get.

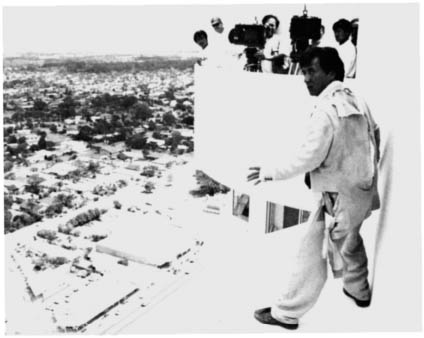

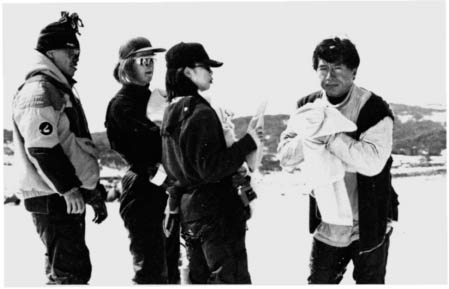

Shooting a scene for First Strike high above Brisbane, Australia. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

One year before cameras for the $15-million First Strike would roll, Tong found his story on the news. “I was watching CNN, and there was this story about three guys smuggling U-235 (uranium 235) from the Ukraine to West Germany and then on to New York. Before they could head back to the Middle East, they were caught by the FBI in the airport.”

Using this premise, Tong’s international locales, and Chan’s “caught in the middle” character, First Strike has one of the best plotlines ever used in a Jackie Chan film. Chan plays “Jackie” (dispensing with the Police Story character name altogether), who is hired by the CIA to follow a girl by plane to the Ukraine. Once there he is free to return home to Hong Kong—a “piece of cake”—but when he sees that she is captured by the Ukrainians, he follows them to a ski resort. After an intense chase in the snow via snowmobiles, skis, and snowboards, Chan’s team is wiped out, and he is left for dead. He is picked up by the FSB (Federal Security Board—a new KGB) which eventually hires him to follow a Chinese-American ex-CIA agent, Tsui, who is smuggling a nuclear warhead to trade into the wrong hands. On his mission, however, Chan becomes confused as to whom he should really be working for. When he gets framed for assassinating the leader of an Australian-Chinese mafia, he is on the run with no one to turn to but himself.

The plot is enough to keep audiences intrigued, and the acting is solid, especially compared to Rumble in the Bronx. The film used Taiwan’s most acclaimed actor, Jackson Low (as Tsui the ex-CIA agent), and Russia’s equally praised Yuri Batchov (as head of the FSB) in lead roles.

Chan’s spy manages to bungle every favorite Bondism. In the ski scene Chan doesn’t flawlessly carry on down the mountain with finesse: he trips and falls at every turn. When he gets his hands on a neat gadget, it’s stepped on and broken after its first use. When he comes into contact with Tsui’s sister, who tries to slap him, he nonchalantly blocks it, only to be kicked in the shins painfully. Looking at her shoes, he finds that she’s wearing steel-toed boots. In readying himself to go home, Chan dresses up in a flashy suit that minutes later is ripped up courtesy of a murderous, giant Russian (Nathan Jones, acting with a broken right arm from a recent strong man competition). And finally, when Chan’s character feels so at ease with his task that he starts singing, he is caught by the man he was following and forced to strip naked, showing off his derrière to female passersby.

Chan, underdressed in the Ukraine and with alarming head gear, proves he’s no James Bond in First Strike. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

Chan inspects the lion prior to the funeral sequence. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

Tong uses his new locales and other devices to highlight cultural differences. When Chan becomes lost, not even having his bearings (another defused Bondism), he must read a Russian sign to his CIA contact and a translator on a mobile phone. He gets a puzzled look on his face and finally blurts out, “Backwards N?!” which only the Russian translator understands. When Uncle Seven, Tsui’s mafia boss father, is killed, Chan tries to convince his superiors that Low will be at the funeral. Chan’s superiors challenge him on this, and he explains that it is a ceremonial duty for the only son of the deceased to carry out the funeral traditions. There is even a reference to differing Chinese beliefs with the funeral sequence in general. White is the symbolic color of death, the one most often associated with funerals in Chinese culture, yet the scene in First Strike is in black and white. Tong explains, “The reason why we put black with the hearses is because the character in the scene . . . has lived there [Australia] for so many years—it’s a mixed culture. Australian-Chinese is very different from Hong Kong Chinese.” Several times during the film, Chan even has to ask the other Chinese players to speak in Mandarin instead of English.

Stanley Tong’s storyboard for a sequence never shot. (Courtesy of Stanley Tong and Golden Harvest)

Even a difficult stunt was storyboarded for Tong’s brand of action. (Courtesy of Stanley Tong and Golden Harvest)

Once again Tong uses a great deal of light humor to break the dryness of the story. From Chan wearing koala bear underwear to sucking on a bloody thumb to avoid a shark attack, First Strike is appealing to those who like something cute or humorous to balance out the more masculine antics of spies, international espionage, and good, old-fashioned action sequences. As for the action itself, the film changes the whole shooting match on the audience for the third time. Supercop was all Tong, Rumble was more Chan, and First Strike is almost all Tong, except for one of Chan’s classic prop fights.

When this film was released, hardly anyone noted its story, acting, and settings as benefits. The action—or lack of it—was the main topic of concern about First Strike, and Chan’s fans weren’t satisfied. Tong’s defense is that “Jackie has already done so many different types of action sequences and has fought for so many years, that it’s hard to find something that has never been done before. We had to come up with something like this to compete with the big-budgeted American pictures.” Tong is correct in the sense that Chan has fought so many times on screen that it would literally be impossible for him to throw some new kind of punch or kick. His theory also translates into bringing realism to the film where exhaustive kung fu sequences would look implausible.

The film does have complete diversity of action, from the large-scale ski battle to the funeral gunfight, from Chan’s tangle with ladders to the underwater finale with sharks and armed scuba divers. The amazing ski attack, a lavish display of Tong’s masterful use of the widescreen, showed off the beautiful scenery of Falls Creek, Australia. The sequence was shot over the course of twenty-five days, and Chan received only four days of training for the snowboard.

Tong adhered to his complex storyboards for filming the sequence but ended up cutting two of the scene’s potential gags. The more complex one sends Chan flying over the top of a tall pine, so that he grabs the top of the tree as he passes over it. Pulling the top back like cocking a spring, he lets it go, hitting the unsuspecting bad guy skier in the face. According to the storyboards, it would have been an amazing shot if it had made it into the final cut. In the other excised sequence, inspired by a similar gag in The Spy Who Loved Me, Chan was next going to topple down a three-story-house’s rooftop with several skiers right behind him. Since helicopters were dropping these skiers right overhead, the gag would have had one of them fall directly into the chimney. Upon landing on the ground, in another fantastic one-shot, two skiers would come racing right over Chan’s head!

The ski sequence that does make the final cut is exhilarating, building up to a climax that sends Chan jumping off of the mountain onto a helicopter, only to have his cap clipped off by the helicopter blades! Before the helicopter is blown up by the attackers’ helicopter, Chan falls into an ice-covered lake, breaking through the ice into the freezing water. Although Tong did the fall from the helicopter, Chan was the one who nearly got hypothermia by staying in the water too long wearing next to nothing.

After the comical chase scene of running away from the giant Russian, Chan directs the trademark Jackie Chan fight scene inside of an Australian museum. Without storyboards, it was back to the improvisational style for which Hong Kong fight scenes are known. It took fourteen days to film the seven-minute scene, and ranged from hand to hand to poles to dragon heads to ladders. Though it ranks as another classic fight montage, something was missing. Chan fights throughout the entire scene completely in defense. He does not engage the enemy but merely reacts. This is perhaps the one flaw to Tong’s take on Chan’s action. Usually, Chan reacts until he can’t take any more, and then he turns into the aggressor. At no point does this happen in First Strike.

First Strike’s detailed plotline brought Chan out of his world and into a more realistic setting. There is no denying the restraint of Chan’s First Strike character, but the film tries to stay as realistic as possible. Since Chan’s own genre of filmmaking exists in a microcosm of pseudo-reality where implausibility reigns, it’s only fair to let Tong keep that character at bay. First Strike is the first Chan film to try to stay story-driven instead of letting the character run amuck. Even Supercop had its own brand of zaniness to exploit its humor as well as its characters.

Real ice.

Real cold. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

Yet the realism breaks down: The film’s finale is the most unrealistic sequence in any of Chan’s films. The twenty-minute underwater battle has Chan and Tsui’s sister (Chien Chun-wu) trying to retrieve the U-235, while the bad guys do the same. The extra obstacles are that Chan doesn’t have an oxygen tank and there are man-eating sharks in the aquarium tank with them. There are some great moments, but the sequence drags on far too long, and some critics found it ridiculous. Tong defends the finale: “Everyone in Asia likes that scene. I don’t think any other action star could get away with it, but for Jackie Chan, it’s okay to have him do silly things.”

Originally, underwater specialist Ron Taylor of Jaws fame was to aid in shooting the climax, but Tong had to take over since Taylor had no experience shooting an action sequence of this magnitude. Tong spent nearly a million dollars in constructing a tank for the film, but it kept leaking every day. Finally, Tong moved to shooting in a real aquarium, but the set had to be dismantled during business hours for tourists. Tong also built three mechanical sharks, though he says that most of the shark footage in the film was of the real thing. A shot of a diver’s leg hanging out of a shark’s mouth, however, is part of the silliness that undermines the realism Tong was trying to bring to the film.

In the end First Strike looks like a $40-million Hollywood film with real action. Even the rockets fired from helicopters were on wires, with just a touch of animation to conceal the obvious. No computer effects or miniatures—everything was done right there. Unsurprisingly, postproduction lasted only ten days after principal photography. If this film had been done in America, CGI effects would have replaced the mechanical sharks and most of the stunt work, putting postproduction time into months instead of days. No joke.

Tong doesn’t consider himself a Hong Kong filmmaker but an international filmmaker: “I was always told that if I wanted to make an American film, I would have to go to America, but it would not work in Asia. And vice versa. I don’t believe it. If you shoot something Hong Kong style, you will show favor to Asian tastes. If you shoot something international style, you will favor international tastes.” Tong is an honest, hard-working filmmaker who is still young enough to have dreams of making his kind of movies, not Hollywood’s longer music videos.

Having signed with Ruddy Morgan and Associates to represent him, Tong was immediately inundated with projects from many different film companies. Tong’s American debut will not be a typical action film at all, but a live-action version of the popular cartoon “Mr. Magoo,” starring Leslie Nielson. Tong’s real test will be an expensive international film entitled Wet Works, described by Tong as a “reinvention of Charlie’s Angels meets Mission: Impossible.” Scripted by Tong, the film will star one Chinese woman (popular Hong Kong actress Christy Chung), one African-American woman (Halle Berry), and one Hispanic-American woman (Salma Hayek). They are in for a ride since Tong plans on having this trio perform their own stunts.

Ad for To Kill with Intrigue. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

Chan fights Kam Kong in Half a Loaf of Kung Fu. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

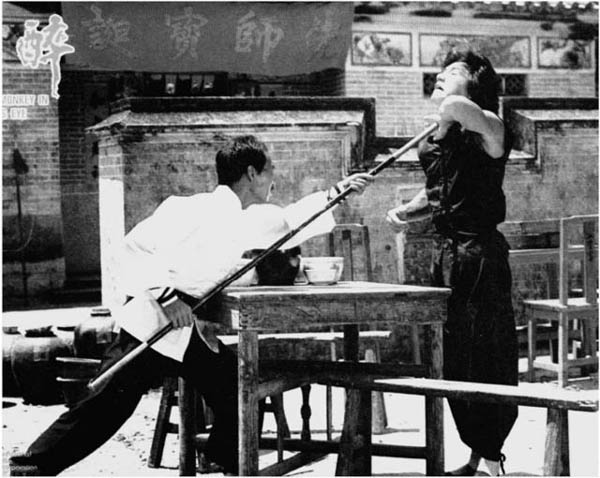

Drunken Master. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

Chan choreographed a fight with Angela Mao for Dance of Death (1979), directed by friend Chen Chi-hwa. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye)

The incredible kick of Dragon Lord. (Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

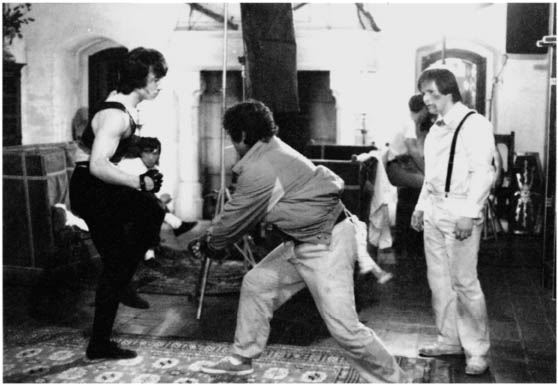

Chan, Sammo Hung, and Benny the Jet Urquidez choreographing Wheels on Meals’ climactic fight. (Courtesy of Sara Urquidez)

Chan is an adventurous archeologist in Armour of God. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

This flip in Armour of God looks dangerous, but a simpler stunt almost cost Chan his life. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Armour of God (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Project A II (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The Three Kung-fu-teers: Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao, and Chan in Dragons Forever. (Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Supercop. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

City Hunter. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

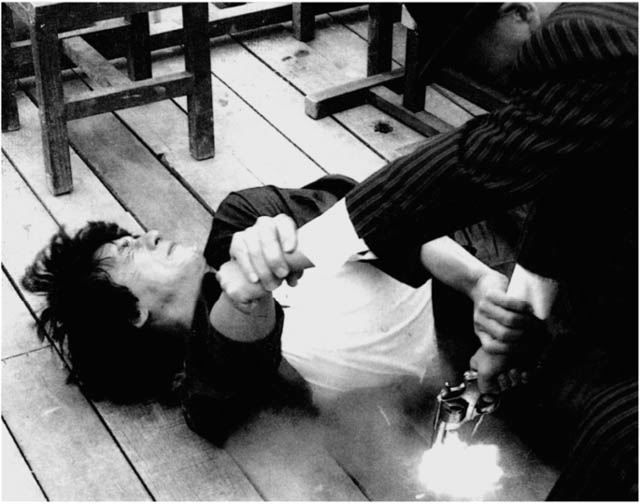

Above: Kung fu “the traditional, original way.” Wong Yat-hwa and Chan in Drunken Master II. (Courtesy of Edward Tang)

Left: First Strike. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

Below: Mr. Nice Guy: Sammo Hung and Chan on the set (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)

With Tong’s bright outlook, anything is possible. However, the Chinese part of Tong will not be diminished even if he is making a Hollywood film: “I was born and raised in Hong Kong, so I don’t think I could make as good of a straight American film as an American director. I still have many stories to tell about Chinese culture, so I want to try and combine the two until I can learn more about American culture.” Part of that culture, in terms of the cinema, is using that eight- to twelve-week shooting schedule to work in the inventive action sequences for which Hong Kong directors are known. One only hopes he will have more luck in America than John Woo, whose style has been watered down in paint-by-number buddy pictures.

Stanley Tong directs First Strike’s funeral sequence. (Courtesy of Golden Harvest)