The worst is yet to come: Project A. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Buster Keaton is the greatest action star the world has and ever will see. During the 1920s Keaton performed stunts, flips, and falls without any special effects or camera tricks. No stuntman could equal Keaton’s abilities. Many times he would double out for other stars, and the fact that many of his gags had to be executed without cheating the camera was proof of the man’s athleticism—and guts, for that matter. Keaton would even use wide angles to present his amazing stunts truthfully (compensating for early cinema’s limited technology). And part of the excitement of a Keaton short or movie for the audience is their awareness of his abilities—you never knew what kind of stunt Keaton’s characters would find themselves in, but you knew he’d be doing it himself. An audience would be on the edge of their seats with breathless anticipation and then admiration. So, it’s no wonder that Jackie Chan brings up Keaton’s name every time someone hails his own stunt work. Hollywood no longer has an action star with the athletic skill and grace of Keaton.

Today’s Hollywood action films may have multimillion-dollar special effects to create the largest gun battles and explosions the world will ever see, but they’re often missing the human element and verisimilitude that drew audiences in the first place. Guns no longer have rounds, since a scene has to keep going longer than what a “normal” firearm would allow it. When anyone gets shot, for some reason unbeknownst to medicine, blood immediately spouts from the person’s mouth. A hero can run blindly through a field of crossfire without getting touched, yet his gun can mow everyone else down in the process. A person can get kicked through a glass window without so much as a cut.

Chan hangs on for dear life on the hovercraft for the finale of Rumble in the Bronx. (New Line Cinema)

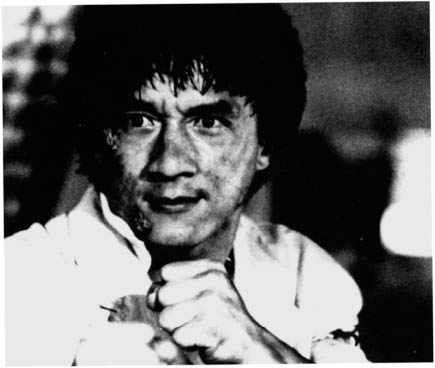

Chan’s intensity in Police Story II. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Armour of God II. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The end result of all this is the distancing of the hero from the audience—the hero is practically deconstructed. Heroes have to be seen as being heroic, and they also have to take bumps and bruises to overcome adversity. Technology has taken over for the blood, sweat, and tears of a skilled stuntman, not to mention of the actor for whom he or she is doubling. With blue screen and CG (computer graphics) animation, no one has to do anything anymore. In Cliffhanger Sylvester Stallone’s incredible mountain-climbing scenes were actually done using matte paintings with computer-enhanced snow falling in front. As for America’s biggest action star, Arnold Schwarzenegger, he has to be doubled running in the snow at the beginning of True Lies. Even martial arts stars like Jean-Claude Van Damme and Steven Seagal use doubles for their own martial arts sequences! Why do audiences popularize stars whose ridiculous salaries preclude them from actually doing what they appear to be doing?

Hong Kong cinema has bred the last great action stars that the world can appreciate. Look no farther than Jackie Chan. He (as do many other Hong Kong action stars to a lesser degree) works very hard to create the realistic action sequences and fights that will make audience’s jaws drop. Even more important, he has the skill—through his extensive martial arts, Peking Opera, and acrobatic training—to do it. So much the better if it looks dangerous. The audience’s identification with his heroic characters is thus never shaken (it’s not so difficult to suspend disbelief). In fact, their admiration extends beyond Chan’s characters to Chan himself.

Even though his films exist in the same world as Hollywood action films, Chan’s style is completely different. His films blend action and humor in a way that no one else can duplicate. This chapter will focus on shooting a martial arts fight sequence the Hong Kong/Chan way. In the circles of Hollywood, any one action scene will include numerous people to choreograph, direct, and edit. Ideally, the choreographer may be a well-known martial artist, the director may have an idea as to what an action scene is supposed to look like, and the editor may have a feel for how a fight scene should be edited. Unfortunately, this scenario is far from accurate in describing the Hollywood action set. For a fight sequence to be executed properly, all three of these components must be in perfect synch. Hong Kong action films have a firm understanding of this synergy because Hong Kong takes its action seriously.

Technique. There are not many fight choreographers in Hollywood because Hollywood directors do not need someone to show them what to do—or so they think. The Hollywood director needs the choreographer to put something together to work within the director’s style. With so many martial arts films being produced, it’s hard to believe that Pat Johnson sticks out as being the only Hollywood fight choreographer to assist in the major productions. Johnson was a competitor, instructor, and referee in American karate, and his work has been seen in Enter the Dragon, The Karate Kid, and Mortal Kombat. Johnson’s choreography can be described as “going through the motions,” and it remains stagnant from film to film.

When watching Mortal Kombat, notice that two of the fight scenes (Johnny Kage vs. Scorpion, Lo Kane vs. Reptile) look far superior to the rest. This is because New Line Cinema let former Hong Kong action star Robin Shou (who played Lo Kane) choreograph these sequences Hong Kong style.

Champion kickboxer Benny “the Jet” Urquidez, a relative newcomer to staging fight choreography, adds an important dimension. Still, he has concerns regarding this art. “A lot of these stunt guys are still doing the John Wayne style: ‘Ah, c’mon, none of that chop-chop stuff; the audience isn’t going to believe that.’ What they don’t understand is that is how I really fight in the ring,” explains Urquidez.

When someone goes to see a film that is being sold as a “martial arts film” or “fight flick,” they want to see just that. In some cases, technique can get in the way of things. When Steven Seagal first came on the screen in Above the Law (1986), audiences marveled over his unique fighting style, which was aikido. Aikido doesn’t contain any kicking, but in his later films, Seagal throws very amateurish kicks, something that he just can’t do well and doesn’t look good trying. Fight choreography should work in the performer’s favor, not necessarily the director’s, because the audience is the one that suffers in the end. While martial arts styles may seem similar, good technique—and even more importantly a complex use of good technique—is the key to staging an enjoyable fight scene.

Jackie Chan has lost his ability to differentiate styles but, fortunately, not techniques. Chan began his martial arts training under his father, who taught him Kung Kar, a rare Shaolin form. As his training continued, he did what all well-rounded martial artists do: work around the styles to create his own. The following account is taken from one of Chan’s appearances in America. A fan asked him about his martial arts training. “I first learned the Southern style [of kung fu]!” Willie Chan steps in and whispers something. “Oh, sorry, I studied ten years in the Northern style. Then I learned the Southern style and mixed the two together. It’s the same as Bruce Lee.” Again Willie steps in. “Well, whatever! [Laughing] I then studied karate, hapkido, judo, and boxing. In my movies it’s like a Caesar salad: it’s a little bit of everything.” He uses good form, but you can’t necessarily identify a particular martial arts style unless the scene calls for it (as in Drunken Master). When Chan got into freestyle brawling in Project A, he abandoned the start-and-stop dynamics of kung fu and developed a realistic, rhythmic motion.

Rhythm. The most important aspect of fight choreography is rhythm, since that is what choreography is in the first place: arranging a dance. Would Gene Kelly jitter, or would he glide across the dance floor? Keith Vitali noted the process: “The best lesson I ever learned in fight choreography came when I was working on Wheels on Meals. I remember walking up to Jackie, and he was tapping the side of his leg, sort of jogging his head back and forth. When I asked him what he was doing, he said, ‘I’m choreographing our fight scene.’ ” In working through the choreography, the performers must get the timing and rhythm down. When the moves are mapped out like dance steps and the rhythm is constant, even the most inexperienced fighter looks seasoned.

In a Jackie Chan fight scene—or just about any other Hong Kong film, for that matter—the audience is treated to constant motion from all parties involved in the fight, just as a real-life fight is full of constant motion. The moves may not look that pretty in real life, but the motion is as realistic as it gets.

In a Hollywood fight sequence, on the other hand, notice that only one man moves at a time, essentially using the other combatant as a frozen punching bag. Then that same punching bag either blocks or throws another punch or kick, forcing the first combatant to remain still. This of course sets up Van Damme to jump up and throw some amazing kick in slow motion, the victim just standing there and taking it. The rhythm is plodding, repetitive—and the fight is static.

Environment. Hollywood prides itself with having great sets in fight sequences, but they never take advantage of their details. A garbage can lid or a bottle is used on rare occasions, but they really don’t add much to the scene.

The invention of a Jackie Chan fight scene lies in his ability to use the environment in his favor. While Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin are notable influences, Chan takes his amazing fight choreography to new heights by his use of props. During the seventies Chan used his first real prop, the sawhorse, a narrow wooden plank with two supporting legs nailed to each end. Throughout the streets of Hong Kong and Asia, sawhorses (otherwise known as small benches) could be found on every corner. In southern China, a martial arts form by the name of Ban Deng Shu was even developed to use these common objects as weapons. One can see Chan’s abilities with the sawhorse in both Drunken Master films and in The Fearless Hyena.

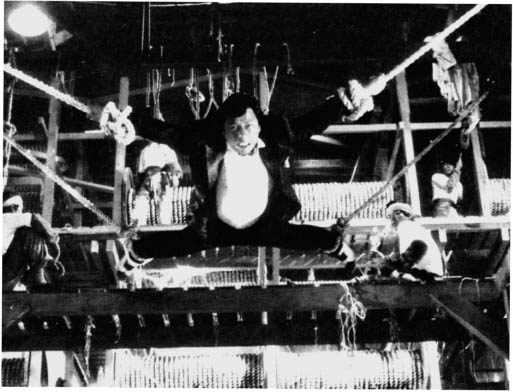

Eventually, Chan’s environmental use would be the one defining trademark of his personal fight sequences, compared to those by Sammo Hung or Yuen Woo-ping. The gang’s pack rat hideout in Rumble in the Bronx is the perfect location for Chan to use an empty refrigerator, a pool table, a snow ski, empty bottles, and pinball machines to defeat his many foes. A car-testing center makes for an interesting action set in Twin Dragons, complete with a heat room with burners lining the walls, a water room that rains, and a garage where emergency cones, tires, wrenches, speeding cars, and hoses all come into play. One of the most ingenious settings is in a rope factory, making up the finale in Mr. Canton and Lady Rose. Gigantic spools of rope, ladders, and wooden beams all become a part of the scene inside an elaborate webbing of rope that connects multiple compartments of the building. While typical action films thrive on exotic locations that add flavor to the film, most of Chan’s fight settings are part of everyday life. Their seemingly awkward logistics give Chan the creative challenge to arrange some of the best action sequences ever put to celluloid.

A Chan film’s inventive prop usage starts with Edward Tang. “Aside from the dialogue scenes, I basically have to think of the reasons why there would be a fight and what props can we use to fight with.” Tang’s original brainstorming is nothing compared to Chan’s wheels in motion. “Everything is totally spontaneous—I mean, Jackie would come and pull out a stunt mattress, lie down for an hour, and try to come up with the next sequence of moves—that’s how it works,” said Richard Norton. Chan’s fight sequences are developed in stages, and so are his props. After something has been used exhaustively, he will go on to the next part of the fight using something else. With each prop even more invention and complexity are added to the sequence. In First Strike, for example, the scene starts with hand-to-hand combat, then wooden poles, then a row of dragon dance heads, then finally ladders. When Chan starts jumping through an expandable ladder, flipping it around as he would a sawhorse, the momentum created cannot be topped, so the scene ends: Chan lowers the ladder to the floor, and sits on it with an exhausted look on his face.

The rope factory fight in Mr. Canton and Lady Rose shows Chan’s ingenuity with environment and props. (Colin Geddes/Asian Eye. By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

Chan’s environment can also enhance his personal fighting ability. When being chased at the climax of Project A II, Chan must chew a handful of Chinese red peppers and wipe the juices on the faces of his foes to render them blind. Inside of a fireworks factory in Police Story II, Chan can’t seem to get even a punch off at his wiry opponent (Benny Lai) until he starts bombarding him with little pop bombs. In Drunken Master and Drunken Master II, Chan’s only recourse to come out ahead is to drink alcohol to enhance his drunken fist boxing skills.

The main difference between Hollywood and Hong Kong action-directing styles lies between shooting masters and shooting segments. A master shot is where the camera is pulled back to show the setting and all of the principal elements of the scene. It sets the mood and shows a vantage point of distance. Masters are shot with one camera fixed at one particular point, whereas close-ups and medium shots can be filmed by alternating different lenses. Master shots are best used for dialogue sequences. In the opening shot of Blade Runner, a master shot with a wide-angle lens shows a large table with two people sitting at either end. To back up the master shot, director Ridley Scott then cuts to a shot of one person looking at the other and vice versa. Close-ups and other techniques can be used, but the director returns to the master shot, which paints the atmosphere as being cold and uncomfortable. Hollywood directors typically stick to masters for action sequences, restraining the dimension of the action and revealing the weaknesses in the choreography. Since Hollywood directors spend little time on fight sequences, masters are easy to set up, and fight scenes can be shot in just a few hours.

Hong Kong directors rarely use master shots for fight sequences, opting for segment shooting instead. Although it takes longer to complete, segment shooting allows the director to shoot a number of movements, designed for only that shot, before moving the camera to repeat the process with a different set of movements. The lighting, the grips, and every other part of the filmmaking process has to be altered, as well, to keep the set’s aesthetics in check. “They will do thirty or forty takes on parts of a fight, if necessary, and there is no master to a fight because they don’t know after the first three or four techniques what the next movements will be,” says Richard Norton.

All of Chan’s fight sequences are achieved with segment shooting, and each fight takes over a month to complete. Typically, Chan will shoot a fight with a rather wide lens (18 to 35). After a few movements have been filmed, he will cut to a medium (50) or possibly a close-up (85), before he switches to another wide shot of the action to start the process all over again. A perfect example of this process is the first drinking scene in Drunken Master II. In between each segment of movements, Chan inserts medium shots of Anita Mui and her crew retrieving the alcohol for him to drink and cheering for him once the fight starts. These inserted shots are important because they show facial reactions, lighten the tone, and create transitions between the segments. This is how Chan shoots every single fight sequence. Chan doesn’t use a lot of fancy camera techniques to enhance the action, because he wants the audience to see what is going on at all times. Chan’s fight scenes suffer the most when they are not seen in the correct aspect ratio of 2.35:1, known as the scope format. The composition of the fight is completely ruined if it is not seen in this ratio.

Sammo Hung has been called the best action director around because he can quickly direct and choreograph a scene, while using different techniques to enhance the effects. Chan usually keeps the camera stationary when shooting a scene, but Hung uses a more experimental approach. He sets up a fight sequence with his trademark tracking shot, which circles the combatants and sets the tone for the battle at hand. It’s anybody’s guess as to what comes next, since Hung employs so many different techniques, like carefully placed overhead and low-angle shots. Hung will shoot in segments using wide angles, but many times he will shoot tighter with closer lenses, allowing him to concentrate more on the fighting techniques performed. “Sammo can set up a shot, shoot it, and move on to the next without any deliberation,” remembers Chua Lam, a regular Hung collaborator.

Editing is the crucial element in tying together the direction and the choreography of the fight sequence. Often referred to as the montage, it is “the principle governing the organization of film elements, both visual and audio, or the combination of these elements, by juxtaposing them, connecting them, and/or controlling their duration.” An editor who does not understand action can ultimately ruin the montage despite the director’s and choreographer’s talents.

Chan’s segments and close or medium shots are linked with perfect accuracy, allowing the audience to see all of the action and gain insight into what the performers are feeling. The major distinction between Sammo Hung and Jackie Chan lies in the editing process. Chan’s edits will signify changes in speed, but his cuts generally leave the action altogether for moments of subtlety. Hung on the other hand, slices and dices his action to speed up the intensity.

While both directors cut on the axis—whereby a singular shot of a kick or a punch will be carried over to another shot of where this movement will land—Hung does something entirely different. In Hung’s fight scenes there are often many different groups of people fighting. Hung will cut on the axis, but the move will break the temporal plane, allowing the movement to actually carry over to another fight entirely. This moves the action along, creating a frenzy of intense camera work and keeping the audience on its toes. Hung’s most impressive and innovative fight sequence to date is the fight in the pachinko parlor in Thunderbolt (1995). Many fans were turned off by the varying camera angles and speeds and the use of wires, but the action is edited to perfection. The colorful set also gave the fight more dimension, and Hung was able to employ different fighting styles (such as sumo wrestling) since the battle takes place in Japan.

To summarize the filmmaking process in a Hollywood scenario, the director, fight choreographer, and editor usually can’t make a fight scene work. The lack of synergy between the three is part ego, part misunderstanding, and part lack of effort. The Hong Kong scenario is quite different because the director, fight choreographer, and editor all understand the process, and, often, are one and the same person. Editing isn’t saved for the end of the shoot; it’s done right on the spot to keep the constant flow of ideas fresh and coherent. If a director does not know how to shoot action, an action director is hired to do just that.

British martial arts actor Gary Daniels has been trying to crack the American scene for the past few years, but he has come to realize that only Hong Kong can really bring out his qualities as a martial arts actor. He was supposed to film an $8-million American production in Africa with a group of other martial arts heavies but instead took a small-budget film entitled Blood Moon for Ng See-yuen. The reason? Instead of filming another lackluster martial arts effort, Daniels wanted the chance to have another film (other than City Hunter) under his belt that showed the proper relationship between direction, choreography, and editing.

In understanding the difference in regards to Chan, watch the end fight sequence in the Hollywood version of The Protector, then in the Chinese version. Chan didn’t have the time to reshoot everything, but watch how his editing, direction, and choreography make the scene infinitely better than the Glickenhaus version. Hong Kong films may never have huge budgets to work with, but they will never be championed in terms of detailing the best action scenes around.

To keep the action genre more in the mainstream, humor is inserted to lighten the tone. Comedic elements vary in style between America, Jackie Chan, and Sammo Hung. One-liners shape the Hollywood style, though they set up a striking contradiction in tone. In Lethal Weapon, for instance, Danny Glover and Mel Gibson bounce off endless one-liners, making the audience laugh, then in seconds, they pull out their guns and start blowing people away, with blood going everywhere. Technically, the comedy and the action are never taking place at exactly the same time, but one can’t help but see the drastic tonal change from good-hearted fun to supposed heroic bloodshed.

One-liners do not exist in Hong Kong action films at all, thankfully. Jackie Chan creates comic gestures in the implausibility of the movements themselves. In a real fight no one would perform acrobatics or stand there and kick forever. The fights are long and exhausting and without anyone actually getting killed or bleeding to death. This brings up an interesting conception of the American public in relation to the length of fight sequences. Keith Vitali explains: “The biggest difference between a Hong Kong fight scene and an American fight scene is the display of power. That’s why Steven Seagal is so popular. He throws one powerful movement, and that person goes to the ground. In Hong Kong films, someone could jump up and throw a powerful side kick, but the person would just get right back up. Americans take this difference so literally.”

When Bruce Lee came on the screen, there was no chance of his going down or getting defeated. If he kicked or hit you, that was it. In Chan’s quest to lighten everything up, he stages incredibly choreographed fight sequences where the participants really don’t have a pain threshold. While realism is somewhat diminished because of how long a scene lasts, it still does seem to exist because the fighters are doing everything in wide-angle shots right in front of the audience.

Do people pay to see Seagal act or fight? If they pay to see him fight, then why do they have to watch ninety minutes of dialogue just to see a total of five minutes of fighting? It doesn’t make any sense. If one can get over the fact that Chan’s scenes are “implausibly realistic,” at least the audience is treated to seeing him and his stunt team perform a myriad of moves for ten-minute intervals.

In Rumble in the Bronx, the scene where Chan gets pummeled with bottles actually created quite a controversy for Stanley Tong and Chan because the scene used blood. Usually, the only blood in a Chan film is in the out-take sequence, and there was much debate about whether to have it in the scene—always keeping the family audience in mind. But Tong explains their final decision: “We had to have something to show how bad [gangs] are. . . . If we don’t put blood, it doesn’t look right.” Much of the brutality of this scene was inspired by Tong and Chan’s real-life experiences with Hong Kong street violence.

Chan usually tries to keep things light by siphoning the violence out of the action. His other way to lighten the tone of the action is by facial expressions. Classic tough guys broodingly rip into their opponents, and if they get hit, they take it in stride. Since Chan is an underdog, though, his characteristics have to be more human, not like a stone-faced fighter. In First Strike when he gets his hand stuck in the hinge of a ladder, he pulls his hand away and makes pained gestures to the audience. Taking method acting to a new level, when Chan eats the Chinese red peppers in Project A II, his face turns bright red with anguish, as one can see the effects of the peppers in his mouth. In every fight scene, the audience has to see what Chan is feeling, and they know he is not supposed to be the tough guy. “I can’t tell you of an American fighter that has as good of a facial expression than Jackie Chan on the screen. They just don’t show it,” says Keith Vitali.

From a filmmaking standpoint, Chan doesn’t rely on much editing, because it would increase the intensity. Editing creates the perception of a scene’s being more violent than what was originally shot. Chan’s scenes are intense enough, and he keeps everything in wide shots so that they appear like miniature circus acts. The music never has a lot of heart-pounding bass to accent the danger. In Chan’s films the music is like a dance number played out as a background melody, accenting only the rhythm of the movement.

Sammo Hung, on the other hand, has a completely different take on the matter. His fight sequences do show a display of power. If they are long, they are broken down to offset the length. Hung does show blood and bruises to convey pain, but he does not fill his scenes with outlandish movements. He keeps things realistic, so the characters in his films must provide the touches of humor. Hung’s most classic film to use this element is in his 1990 masterpiece Pedicab Driver. At the end of the film, Hung comes upon a group of men who are all eating rice. After setting up the stage of the fight, the camera pans across the men, who are still chewing their food. The camera then cuts to the overweight Hung, who is licking his lips. The montage of shots that follow shows Hung kicking and smashing his opponents with everything he has, forcing the mouths of his enemies to spew up speckles of rice. It’s an awkward approach, but this is how Hung lightens his action. Other Hung examples of humor include Yuen Wah’s cigar chomping in Dragons Forever and James Tien’s caustic laugh in Heart of Dragon.

Hung likes to carry out his fight scenes without music. If music does exist, though, it is accented with booming bass, signifying the power of the scene. At the end of Heart of Dragon (Japanese version), music is entirely left out, with the exception of a crackling beat to mark Chan’s shooting of a man at the top of a stairway.

Chan’s filmmaking style and use of comedy have made his action films the best in the world, but he personally adds one more aspect to them that separates them from the rest. Chan realized that many on his crew and among his Peking Opera brothers could fight as well as perform acrobatics. He wanted to come up with something different.

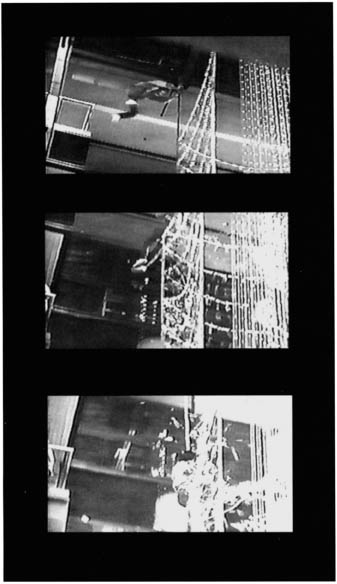

He did it after his fight inside the clock tower in Project A. In a single moment Jackie Chan would break himself from the mold in which men are made, and become an incredibly different animal. With four cameras set up, Chan would do Harold Lloyd one better by falling some fifty feet below from the clock tower. “For seven days, I couldn’t do it. Every day I would dangle with a stuntman close by. Everyone would just stand there watching me. I was scared. On the last day the stuntman did not wait around, and I couldn’t go back in,” said Chan during the U.S. publicity tour for Rumble. When Chan finally let go of the clock hand, he tumbled through two awnings and landed on the ground. He shot that scene not only once, but several times, with three versions making the final cut of the film. Chan did the fall in one shot—in an American film a fall like this would have been edited with three shots to mask the stunt mattress below. The practice of shooting a spectacular stunt in one shot (no cheating with edits) became a trademark of the Jackie Chan stunt scene. It wouldn’t work any other way.

No tough guy: Chan in Mr. Canton and Lady Rose. (By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The stunt he is most known for, however, is not this fall from the clock tower but the relatively easy jump onto a tree at the beginning of Armour of God. Chan had done the jump correctly the first time, but ever the perfectionist, he wanted one more just in case. When the branch broke, Chan plummeted to the ground, the European cameraman scurrying out of his way. Chan landed headfirst on a rock. “I was twenty meters away, and everyone was silent on the set,” said Chua Lam, one of the film’s producers. “We rushed down, noticing that Chan was not bleeding at all, but when we got to him and pulled him up, blood was pouring out of his ears.” Fact is, the rock pierced Chan’s skull. Chan went to a Yugoslavian hospital for two weeks, then he went to Paris to see an American doctor for another ten days. When Chan returned to the set, he was as good as new and showed no signs of his near-fatal fall. Ironically, Chan was hurt by a simple stunt—a lesson he will never forget.

It’s important to mention that many Hong Kong Stuntmen and actors are just plain crazy when it comes to displaying their physical abilities in the cinema. In a no-budget action film entitled Tiger on Beat II, actor Conan Lee made a jump onto a light pole, slipped, and fell straight to the ground. Although it was an accident, the fall makes Chan’s drop in Project A look like child’s play. Many actors and actresses do their own stunts because insurance and unions are not as obligatory to the production as in American films.

Chan and Hung are both very physically demanding on the actors and actresses that appear in their films. In several instances the actors are really hitting each other because the director calls for realism in the fight. To accent this, powder is applied to the bodies of the stuntmen and actors. When they get hit, the powder is clearly seen rising in the air. In Hollywood films stunts are carefully planned out, using numerous technical supports and plenty of preparation time. Hong Kong films are, too, but because they are shot so quickly, they often make the Stuntman take a harder fall than would be necessary. “In Hong Kong, they cheat everything. Tables, lamps, chairs, and benches are all prepared strictly for the one shot of a stuntman hitting them. Hollywood never goes to this much trouble,” says Keith Vitali.

(By permission of Media Asia Group. © STAR TV)

The following is my list of Chan’s ten best stunts. They are put in order of difficulty and cheating. It would be impossible to not get injured falling from a seventy-foot pole, as in Police Story, because of the complexity of the stunt. The fact that Chan has to get up in the same shot and run out of the scene is even more amazing. All of these stunts were undoubtedly performed by Chan himself in all of the shots. To this day, no Stuntman, in America or anywhere else, has been able to duplicate these death-defying stunts.

| 1. | Police Story (1986)—Sliding down a seventy-foot pole, setting off electrical charges, then falling back-first through a wooden awning. He gets up and runs out of the same shot. The stunt was filmed from three different angles. All three appear in the film. Chan skinned his hands badly and damaged his vertebrae. |

| 2. | Project A (1983)—Falling from the clock tower. Three different takes of the stunt are all linked together in the film. |

| 3. | Armour of God II: Operation Condor (1991)—Jumping a motorcycle off of a pier. Chan leaps off his motorcycle and catches a net suspended from a crane, which holds him over one hundred feet above the water. The stunt was filmed with three cameras fixed at the same position using three different lenses. All three (from close-up to wide) are presented in the film. |

| 4. | Police Story II (1988)—Sliding halfway down a nylon tube that is blown in half by a charge. In one shot the charge explodes under Chan’s feet leaving him dangling in the open air as the bottom of the tube settles to the ground. |

| 5. | Police Story (1986)—Driving down the side of a shantytown as it explodes and collapses along the way. Ten of Hong Kong’s best cameramen were assembled to shoot the one-time stunt from different vantage points. It was a real shantytown that was going to be demolished weeks later, anyway. |

| 6. | Project A II (1987)—Running down collapsing building frontage, then the other side falls directly on top of him. This is Chan’s homage to Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, Jr. |

| 7. | Twin Dragons (1992)—Running over the top of a moving car. Some versions show the stunt at regular speed, while others show it in slow motion. |

| 8. | Drunken Master II (1994)—Falling on a bed of hot coals, shot in regular speed and slow motion from two different angles. |

| 9. | Police Story II (1988)—Jumping over the tops of buses. While he is on the top of a bus, he has to leap over the top of a store frontage sign, then fall flat to keep from being hit by another. Finally, he leaps through a window. The only problem was that he leaped through the wrong one. In the final cut of the film, he is leaping through real glass! |

| 10. | Police Story III: Supercop (1991)—Hanging from a rope ladder attached to a helicopter over Kuala Lumpur. The jump on was more dangerous, since he actually was held up by wires while he was supposedly hanging onto the ladder. |

(Courtesy of Seasonal Films)

| 1. Head | 1976, Hand of Death: knocked unconscious. |

| 1986, Armour of God: suffered brain hemorrhage after falling and hitting a rock-the most serious injury in his career. | |

| 2. Eye | 1978, Drunken Master: injury to bone under eyebrow. |

| 3. Nose | 1980, Young Master, 1983, Project A, 1996, Mr. Nice Guy: broken all three times. |

| 4. Cheek | 1992, Supercop: cheek bone dislocated. |

| 5. Mouth | 1995, First Strike. |

| 6. Teeth | 1978, Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow: kicked out by Hwang Jang-lee. |

| 7. Chin | 1982, Dragon Lord. |

| 8. Throat | 1980, Young Master: almost suffocated; injured several times since. |

| 9. Neck | 1983, Project A: dock tower fall injured neck bone. |

| 1996, Mr. Nice Guy: flubbed flip injured neck bone. | |

| 10. Shoulder | 1992, City Hunter: dislocated right shoulder. |

| 11. Hand | 1985, The Protector: injured bones in hands and fingers. |

| 12. Chest | 1990, Armour of God II: dislocated chest bone after falling from suspended chain. |

| 13. Back | 1985, Police Story: slide down five-story pole injured 7th and 8th bones in vertebrae; pelvis dislocated. |

| 14. Knee | 1992, City Hunter: injured while shooting skateboard scene. |

| 15. Ankle | 1994, Rumble in the Bronx: jump on hovercraft pushed bone in big toe through skin—injury still problematic when performing stunts involving the foot. |

| 16. Legs | 1993, Crime Story: both injured when caught between two cars. |