1

Terms and Conditions

If people knew how hard I had to work to gain my mastery, it wouldn’t seem wonderful at all.

—Michelangelo

When you meet someone who speaks a foreign language well, you may attribute her skill in the language to natural ability.1 This is probably because you don’t know about all the hard work that went into achieving this level of mastery. But with the exception of certain people we might call savants, anyone who has ever learned another language as an adult did so only as the result of real effort. In that way, this book is most assuredly not a quick fix. But if you apply the specific skills and abilities you have honed over a lifetime, learning a language can be fun and rewarding. The older you are, the more tools in your toolbox you can take advantage of to reach your goal. Everyone possesses unique sets of skills and abilities that can be applied to language learning—if they can get past some false beliefs. It is to these that we now turn.

Three Myths about Foreign Language Learning

From the very beginning of Richard’s Korean language study, he felt frustrated with his progress. It seemed as if no matter how hard he tried, he was not advancing fast enough. His teachers were constantly encouraging him to study harder and to memorize more. He knew that he was working hard—studying for class, meeting with native Korean speakers for language exchange, watching videos, and learning Korean songs. At first, he thought he had hit the age wall. Richard had been successful when he had studied German, Portuguese, French, and Japanese, but he began the study of Korean at age fifty-two, and he thought that perhaps he was now too old to take on another language. Certainly, according to conventional wisdom, he should not expect much progress.

One day, he was having coffee with his Korean language exchange partner (who has the inviting name “Welcome”). Richard wondered out loud whether Welcome felt his English had improved since coming to the United States. It certainly seemed to Richard that Welcome’s English had gotten better, and Richard was expecting Welcome to tell him that he thought so too. Instead, Welcome said he didn’t know. When Richard asked him what his teachers thought, Welcome replied that because American teachers always compliment students, he couldn’t trust what they told him. Welcome went so far as to wish that his teachers would be more critical. For Welcome, the more they criticized, the more they showed that they were interested in his progress.

This was an eye-opening conversation for Richard. From then on, he realized that his perceived lack of progress in Korean was a function of his own expectations about what it means to be a successful language learner. Richard had been measuring his progress by how much he didn’t know. He saw the glass as half empty, and therefore pushed himself to memorize more and more material. But relying on rote memory alone is the second-worst thing any adult foreign language learner can do.

Of course, memorization is required to learn a foreign language; however, rote memorization exercises (such as listening to a text and then parroting it back verbatim, memorizing long passages of dialogue, slogging through flashcards) place the adult learner at a disadvantage cognitively. Because this ability declines with age, placing too much emphasis on rote memory can lead to frustration, is demoralizing, and can ultimately cause any adult language learner to quit.

You may be wondering, if rote memorization is the second-worst thing for an adult learner, what is the worst? It is the belief that one is too old to learn a foreign language. The next thing we want to do, therefore, is to dispel this, and two other myths that surround language learning in adulthood.

Myth 1: Adults cannot acquire a foreign language as easily as children.

On the contrary, there is evidence to suggest that adults can learn new languages even more easily than children. There are only two areas where children may be superior to adults when it comes to language learning. The first appears to be their ability to acquire a native accent. It is certainly the case that normal adults are capable of achieving native-like fluency as well. But even if an adult language learner is more likely to speak with an accent, there is no reason to be overly pessimistic about it, as long as it does not interfere with intelligibility. Children’s other advantage over adults is that they have no language learning anxiety. In other words, because children aren’t burdened by a belief that they cannot learn a language, they are free from such self-defeating thoughts.2

Myth 2: Adults should learn foreign languages the way children learn languages.

Children’s brains and adult brains are different. Therefore, why would anyone expect that the same teaching techniques that work for children be appropriate for adults? They aren’t. But, unfortunately, adult language learners sometimes try to learn a language by stripping away all of the strategies and learning experiences that helped them become successful adults in the first place. They try to learn a foreign language “purely,” the way they acquired their first language. This isn’t possible. Trying to do so inevitably leads to frustration and a higher probability of abandoning the goal. A more fruitful approach would be for adults to build on their considerable cognitive strengths and to not envy or try to mimic children’s language learning.

Myth 3: When learning a foreign language, try not to use your first language.

Some adult language learners believe that they should never, ever, translate from their first language to their target foreign language. But this advice deprives adult language learners of one of their most important accomplishments—fluency in their native language. Although it is true that one language is not merely a direct translation of another, many aspects of one language are directly transferable to a second language. It’s not even possible to completely ignore these aspects, and trying to do so can be frustrating.

For example, an English-speaking adult who is learning Portuguese could hardly avoid noticing that the Portuguese word to describe something that causes harm in a gradual way, insidioso, is suspiciously like the English word insidious. It would make no sense to pretend as if prior language skill in English is not transferable in this case. It is true that such cognates are not found between all languages and are sometimes inaccurate (as in wrongly equating the English word rider to the French word rider, which means “to wrinkle”). Nonetheless, looking for places where concepts, categories, or patterns are transferable is of great benefit, and also points out another area where adult foreign language learners have an advantage over children.

Regrettably, any of these myths could prevent even the most highly motivated adult from embarking on a language learning journey. However, there is a great deal of research that addresses such false beliefs. Insights from the field known as cognitive science offer guidance that is directly relevant to the adult foreign language learner.

What Is Cognitive Science?

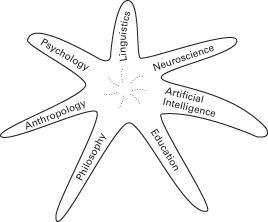

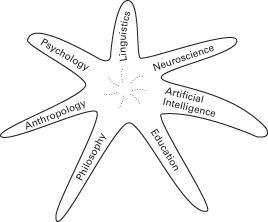

Cognitive science is an interdisciplinary movement that began in the 1960s and became highly visible as a scientific enterprise during the 1970s. Cognitive science occupies the intersection of a number of fields in which researchers from many disciplines explore questions about the nature of mind. The disciplines centrally involved in this endeavor include psychology, linguistics, philosophy, neuroscience, artificial intelligence, and anthropology.3 The field of education is now commonly included as well (see figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

We chose the seven-armed starfish (Luidia ciliaris) to illustrate the field of cognitive science. Like the arms of a starfish, no one branch of cognitive science is more important than another. The arms must work in concert for the starfish to move. There is no head or tail, but all of the arms radiate from a “central executive.”

As a scientific movement, cognitive science is notable because it represents a deliberate shift away from extreme specialization. Cognitive scientists actively promote inclusivity and the adoption of new points of view, and this cross-fertilization has produced hundreds of important new research programs. It is still the case, however, that cognitive scientists are generally trained in one of the specific disciplines shown in figure 1.1. For example, Richard and Roger were trained as psycholinguists in experimental psychology programs; however, they are also cognitive scientists because their graduate training emphasized cognitive science and their research and ideas are influenced by these related disciplines.

Before discussing how cognitive science relates to adult foreign language learning in more depth, we first need to define some terms.

Mind the Gap

In describing mental processes, cognitive scientists frequently categorize them as being either top down or bottom up. Top-down processes, which are also referred to as conceptually driven processes, utilize what you already know in service of perception and comprehension. For example, experts solve problems differently from novices because they have more knowledge and experience in a given domain.

Although top-down processing applies to cognition in general, it plays an important role in the comprehension of spoken language. The environments in which we speak to one another are rarely very quiet ones—think about the last time you met some friends for a meal in a restaurant. Even in a relatively quiet establishment, your conversational partners will be competing against background noise and the voices of other patrons. And if it were necessary for your ears to pick up every sound spoken by your dinner companions, you simply wouldn’t be able to understand much of what they said—there is too much noise to contend with. Fortunately, the cognitive system is able to fill in the missing information, even without you being aware that this is happening. This is why background noise is more disruptive for beginning language students than it is for advanced students—without greater knowledge of the language, top-down processing can’t fill in what’s missing.

Although top-down processing is clearly very important, it’s not the whole story. Bottom-up processing, which is also referred to as data-driven processing, is the opposite of top-down processing. This term refers to situations in which you perceive a stimulus without preconceptions or assumptions about what you’re experiencing. Instead of being guided by expertise or familiarity, bottom-up perception depends solely on information that comes from your five senses. For example, vision and hearing are mostly bottom up until the brain can make sense of what was seen or heard. If you wear glasses, then you are correcting for a deficit in the data your eye must use in order for your brain to see. Glasses correct a bottom-up problem.

Virtually all language skills require the interaction of both top-down and bottom-up processing. Reading and understanding a short story is a good example of such an interaction. You need to decode the letters and words on the page, and match them against representations in long-term memory, which is bottom-up processing. However, you also have to make use of your knowledge of the characters’ histories and motivations, and how stories work, which is very much top-down processing.4

Adult language learners excel at top-down processing because of their extensive world knowledge and experience. For example, because you already have an understanding of basic narrative structures (think of “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back”), you can capitalize on your knowledge of these expectations while reading in ways younger readers may not be able.5 As we get older, and our hearing and vision become less acute, savvy adult language learners will offset any such decline by drawing upon their greater world knowledge. Insights from cognitive science can show you how to do this.

What Does “Meta” Mean?

Before exploring how this research can help you learn a new language, it is necessary to introduce the concept of meta. Although the meaning of words like cognition, memory, and linguistics is fairly straightforward, you may not be familiar with the concepts of metacognition, metamemory, or metalinguistics. Let’s look at what these are, and why they will be so important in the chapters that follow.

Metacognition, simply put, is thinking about thinking, and metamemory is thinking about memory. Most of the time, cognitive processes function so smoothly and effortlessly that we rarely pause to reflect on them. However, when we are fooled by an optical illusion, or try to understand a friend’s failure to follow simple directions, or mishear what someone said, we may briefly stop and consider the way that our mind works (or momentarily fails to work). This is metacognition, and it is the greatest strength of adult learners.

It’s not easy to infer what children know about their mental processes. Certainly their cognitive skills are improving all the time as they gain more experience in the world. As anyone who has children knows, the changes happen in leaps and bounds. However, the full range of metacognitive and metamemory abilities are not fully developed until adulthood.6 This is hardly surprising, since young children haven’t had enough experience with cognitive successes and failures to be able to make many generalizations based on these experiences. It’s also the case that the consequences of poor memory in young children are rarely serious. Little kids have an incredibly sophisticated external memory device (better known as “mom” or “dad”) to keep track of anything that the child must do or remember. If the child forgets or doesn’t understand, mom or dad is there to help.

Adults, however, have developed a more sophisticated understanding of their cognitive processes, but it’s not perfect and may vary by subject matter.7 Adults have learned, for example, that they can memorize a seven-digit phone number, but not a twenty-digit package tracking number. They know that it’s helpful to mentally rehearse directions that they are given, or to use strategies that make computer passwords easier to remember. But it may not be intuitive how metacognitive abilities can be applied to foreign language learning.

Metalinguistic awareness is somewhat different. It refers to knowing about how your language works, and not just knowing a language. Metalinguistics is not the history of the language, or knowing word origins, but rather knowing how to use language to do things: how to be polite, or to lie, or to make a joke. Once again, this is an area in which adults excel, even if they aren’t really aware that they possess this knowledge. But no one is born with this skill—for example, it’s been demonstrated that politeness routines are learned in childhood from parents, who ask for the “magic word” before their kids are allowed to excuse themselves from the dinner table.8

In adulthood, metalinguistic knowledge can be impressively precise. Knowing the difference between a clever pun and a groan-inducing one, for example, reflects fairly sophisticated metalinguistic awareness.

The good news about metacognitive skills is that you don’t have to learn them all over again when you start learning a new language. Instead, you only need to take the metalinguistic, metamemory, and metacognitive abilities you’ve already developed in your native language and apply them to the study of your target language.