4

Pragmatics and Culture

The Language, the Culture, and You

Throughout this book, we repeatedly point out that adult language learners possess advantages over younger language learners—the most important of which is their ability to reflect on their own language learning process. Nowhere is this metalinguistic ability more apparent, and more useful, than in the study of pragmatics, which is the social use of language. In this chapter we will examine how cognitive scientists have studied pragmatics. Unfortunately, this topic is often ignored in traditional foreign language learning settings. Therefore, it is important to set the scene with some background information before going on to discuss how pragmatics applies to learning a foreign language. To do this, we must think about language at a metalinguistic level.

Because pragmatics is the social use of language, it lends itself quite easily to metalinguistic awareness. In contrast, one’s metalinguistic ability to reflect on the sound system of a language is limited. Young children cannot take a mental step back and think metalinguistically about the sound system of the language(s) they are learning. They also don’t need to do this because they possess the skill of distinguishing, and then later producing, sounds just by hearing them. Even though adult language learners can (and in fact must) consciously think about the sound distinctions between their native language and the target language, doing so never entirely makes up for the fact that sounds not learned in childhood are more difficult to distinguish and produce in adulthood. In other words, just reflecting on the sounds of a language cannot completely compensate for the advantages of early exposure.

Metalinguistic skill is more useful when it comes to learning vocabulary and grammar. In these two areas, research has shown that adults are not necessarily at a disadvantage when compared to children.1 For adult language learners, metacognitive skills can be effectively employed so that words and the rules for combining them can be more easily learned, retained, and retrieved. But as important as metacognitive skills are for learning the vocabulary and grammar of a language, in these areas they only serve as a means to an end. In fact, the goal for using metacognitive skills in language learning is to eventually stop relying on these skills. That is to say, once we have mastered certain words, phrases, or grammatical patterns, we no longer have a reason to consciously reflect on them. In fact, continuing to do so would be counterproductive and would slow down the flow of communication.

Pragmatics, however, is the one linguistic domain where adult language learners continue to leverage their metalinguistic and metacognitive strengths, even after full mastery of a language is achieved. Even native speakers, who automatically produce sounds, words, and phrases, still must consciously reflect on what they say to maximize its effectiveness. Therefore, as the linguistic domain in which adult language learners most excel, we place special emphasis on the importance of pragmatics. We believe that an understanding of pragmatics not only can help the adult learner acquire a new language, but will also help him or her continue to use this language to the fullest.

The successful use of pragmatics requires a deep knowledge of the culture in which the target language is embedded. Not surprisingly, therefore, pragmatic ability is often considered the most advanced aspect of linguistic mastery. For example, according to the ILR Skill Level descriptions, it is only when speakers reach the S-4 (advanced professional proficiency) level that they are expected to “organize discourse well, employing functional rhetorical speech devices, native cultural references, and understanding.” Furthermore, it is not until the S-5 (native or bilingual proficiency) level that speakers are expected to use the language “with complete flexibility and intuition, so that speech on all levels is fully accepted by well-educated native speakers in all of its features, including breadth of vocabulary and idioms, colloquialisms, and pertinent cultural references.”2

We do not disagree with the ILR classifications. Clearly an inability “to use speech on all levels that are fully accepted by well-educated native speakers” would mean that a language learner has not reached S-5 proficiency. We are concerned, however, that important pragmatic aspects of linguistic competence, such as the use of rhetorical speech devices, might be considered too advanced for beginning adult language learners to tackle, thereby putting off the study of these important aspects of the language. This would be a mistake. Delaying pragmatics until pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar are well in hand deprives adult language learners of the richness and subtlety that makes learning a new language such a pleasure. It also misses ways in which pragmatics can reinforce those very skills.

There are three reasons why pragmatics should be included in language study from the very beginning of foreign language learning. First, layering pragmatics into even very basic language lessons gives the adult learner more opportunities to strengthen pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. Second, because it is culturally dependent, the study of pragmatics helps students better understand the culture, which will result in using the language more effectively. Finally, through pragmatics, speakers are able to convey complex meanings naturally and efficiently, which keeps them more fully engaged in their language learning.

Cooperation

Regardless of the target language, there is one pragmatic principle from which all spoken and written communication derives: cooperation. The philosopher of language H. Paul Grice famously described the primacy of cooperation as a conversational imperative in his “Cooperative Principle,” which states: “Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged.”3 In theory, for a conversation to succeed, both conversational participants must try to communicate as effectively and efficiently as possible. But what happens when one of the conversational partners is a nonnative speaker of the language? Grice’s framework can help answer that question.

Grice proposed several rules, which he called “maxims,” that speakers and listeners follow in order to cooperate fully. The first maxim is called the Maxim of Quantity. This maxim states that when you speak, you should not give any more information or any less information than is truly needed to make yourself understood. To give more or less information is to be uncooperative. The second maxim, the Maxim of Quality, states that you should tell the truth. To be less than truthful, therefore, is also to be uncooperative. The third maxim, the Maxim of Relation, is very straightforward: It means, “Be relevant.” And finally, Grice jokingly defined the fourth Maxim of Manner as “be perspicuous,” by which he meant, be clear, avoid being ambiguous, and be orderly.

Unfortunately, in many formalized language learning situations, adhering to these four maxims is all that is asked of teacher and student: Be precise, be clear, be direct, be relevant. But in natural language, as you may have guessed, speaking this way is the exception rather than the rule. People often say too much, or too little, aren’t relevant, or are purposefully vague or indirect. Grice called this “flouting” the maxims. Importantly, when a maxim is flouted, the conversation doesn’t automatically break down for two native speakers of a language. Conversational robustness is maintained because of the underlying assumption of cooperation. Consequently, when a speaker flouts a maxim by saying too much or too little, or is indirect, untruthful, or vague, rather than give up in frustration, the listener tries to figure out just why the speaker chose to speak that way.

For example, consider possible answers to the question “Do you like my tie?” Strictly adhering to the Cooperative Principle would produce answers like “Yes, I like your tie” or “No, I do not like your tie.” These are the kinds of straightforward answers that might be expected in a typical language-learning setting.

But what about the answer “It certainly matches your shirt.” This response is not entirely relevant because it does not answer the question directly. But, if both participants assume each is trying to cooperate, then, although not entirely relevant, the response not only answers the question, but does so in an inoffensive, humorous way. Therefore, by flouting the Maxim of Relation the speaker was able to accomplish much more than merely answering the question with a “yes” or “no.” Notice, however, that by answering in this way, the speaker also ran the risk of being misunderstood.

Here is another example, this time violating the Maxim of Quality. On a very stormy day, you meet a friend on the street who is soaked through with rain and you say, “Lovely weather we’re having.” Clearly you are not being truthful—but your friend may laugh or groan and agree with you. In this case, your friend doesn’t call you a liar—your friend recognizes your greeting for what it is—sarcasm. In other words, not only is the speaker saying that the weather is bad, the speaker is also trying to be funny while at the same time seeking commiseration. Nevertheless, once again it must be pointed out that by answering sarcastically, the speaker could have been misunderstood.

Are there times when we no longer assume a conversational partner is cooperating? Yes. For example, if someone is schizophrenic, the listener may come to the conclusion that the person is incapable of cooperating and therefore no longer works to make sense of what is being said.4 Alternatively, in a court of law, since a hostile witness cannot be assumed to be cooperating, the questioning of such a witness must use different tactics. Conversational cooperation may also be lacking in an argument between two people, where each may feign ignorance, lie, misconstrue statements, or use any means possible to win. But the fact that such examples are relatively rare indicates that conversational cooperation is the norm.

Unfortunately, most foreign language learning environments do not teach students how to flout conversational maxims in ways that are appropriate for the target language and culture. This means that foreign language learners may find themselves stuck in an artificial world of complete and total cooperation—which is as dull as it is unnatural. Or they may try to flout the maxims inappropriately. That is why it is important for adult language learners to learn how to flout these maxims for a specific culture. Although it is possible for nonnative speakers to be misunderstood when they try to flout conversational maxims, the underlying assumption of cooperation is robust enough to keep the conversation flowing without too much difficulty. In other words, there is much to be gained by being just a little bit uncooperative.

Speech Act Theory

For the underlying assumption of cooperation to convey more than a mere statement of fact, all spoken and written communication must be analyzed at three different linguistic levels. Taken together, these three levels tell us “How to Do Things with Words,” which was the title of a collection of posthumously published lectures the philosopher of language J. L. Austin delivered at Harvard in 1955. These lectures form the core of an area of pragmatics known as speech act theory.5

Consider the following situation. You are drinking a cup of coffee at Starbucks minding your own business when a stranger approaches you and asks, “Come here often?” You reply “Drop dead.” At a basic, literal level, “drop dead” is a statement in which you command the person to die suddenly. Such a statement at its most literal level is called a locutionary act in speech act theory. But in this case, “drop dead” is not meant literally. What you are really doing is telling the person not to bother you. Thus the nonliteral interpretation of your utterance (or the illocutionary force of your utterance) means “go away” rather than “die.” Understanding the illocutionary force requires the cooperation of the listener to move past the literal meaning to the nonliteral meaning (also called the figurative meaning). Finally, what speech act theory calls the perlocutionary effect of the utterance—the action or state of mind brought about by that utterance—will depend on what happens next. If your would-be masher goes away, then leaving becomes the perlocutionary effect of having said “drop dead.” If the person laughs and sits down next to you, then this becomes the perlocutionary effect.

Notice that speech act theory does not guarantee a specific perlocutionary outcome based on a particular speech act. Instead, speech act theory serves to remind us that for each utterance, a listener must reflect on what was said literally, figuratively, and also the outcome. For some speech acts, these three levels are all very similar. A statement such as “The sky is blue” may literally be a statement of fact, have no separate figurative meaning, and elicit no effect other than agreement by the listener. A question such as “Is the sky blue?” however, although literally a question about the color of the sky, can figuratively be used as a rhetorical question deriding someone for stating the obvious. Hopefully the speaker gauged correctly and the result was laughter and not a bloody nose.

Figurative Language

Both Grice’s Cooperative Principle and speech act theory illustrate how speakers and listeners have choices when they communicate—only one of which is to speak literally. Unfortunately, because literal language is sufficient to convey meaning, nonliteral, figurative language is often ignored in traditional language learning situations. When figurative language is taught at all, it is seen only as an interesting aside or a fun component to a lesson, which implies that it is not a necessary or integral part of language learning. Not until students are well on their way to mastering pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar does explicitly teaching figurative language begin in earnest. And perhaps there is some logic in this. Which is more important linguistically, to be able to say that a piece of pie is delicious or to say that it’s a little slice of heaven? However, such a narrow view that literal language should be taught before figurative language ignores research in the area of pragmatics, which has shown that figurative speech is as fundamental to a language as its literal counterpart.6

The bias toward literal language in traditional language learning situations may also occur because literal language is meant to be less ambiguous than figurative language. For example, it’s more straightforward to state “I’m hot” than it is to complain “I’m melting” (unless you are the Wicked Witch of the West, in which case she’s speaking literally). In this way, individuals who use figurative language run a greater risk of being misunderstood than those who adhere to the strictly literal. However, as we noted earlier, if Grice is correct in that conversational participants try to express themselves as clearly as possible, you might expect potentially ambiguous figurative language to be rare. This is not the case. It’s hard to imagine any language that does not use figures of speech. A fundamental example involving metaphor would be the English verb to be, which comes from the same root as the Sanskrit for to breathe.7 That’s as basic as it gets.

Figurative language is so common, therefore, that it must be the case that despite its potential ambiguity, it can accomplish discourse goals literal language cannot. In other words, although producers of figurative language run the risk of being misunderstood, there are also substantial benefits that make it worth the risk. Because specific figures of speech and the goals that they accomplish differ from language to language, it is up to you to explore these issues in your target language. To understand the concepts, let’s look at some examples of figurative language in English.

It has not been clearly established exactly how many different figures of speech there are—estimates range into the hundreds. Common figures of speech that have been researched by cognitive scientists, however, include hyperbole (or exaggeration), understatement, irony, metaphor, simile, idiomatic expressions, indirect requests, and rhetorical questions. These eight figures of speech can be found throughout the world’s languages; however, their use may differ from culture to culture, even for those who speak the same language. For example, for a long time Americans have been seen as greatly prone to exaggeration whereas the British are considered to be the masters of understatement. Queen Elizabeth II famously described a particularly bad year in her life this way: “1992 is not a year on which I shall look back with undiluted pleasure.”8 Likewise, some cultures value indirectness (e.g., Japan and Korea), whereas others are considered to be more direct (e.g., the United States). As you can see, figurative language is the Swiss Army knife of communication.

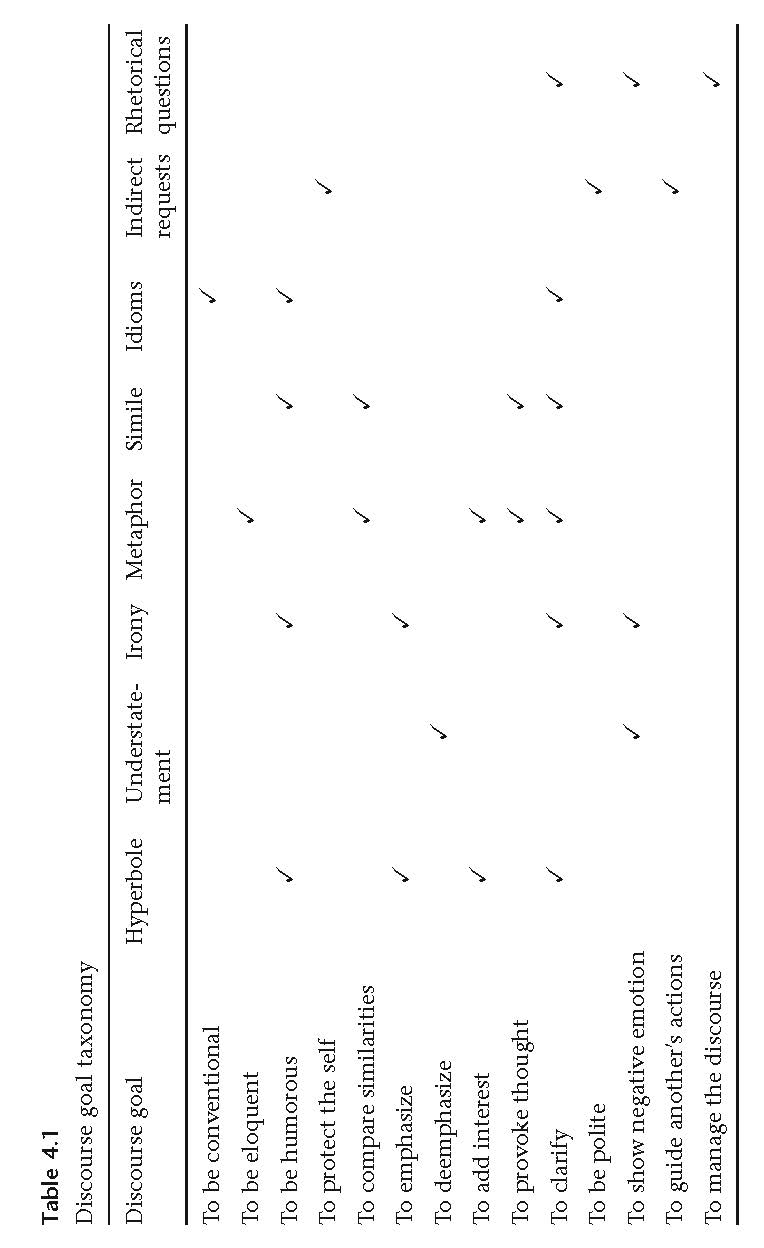

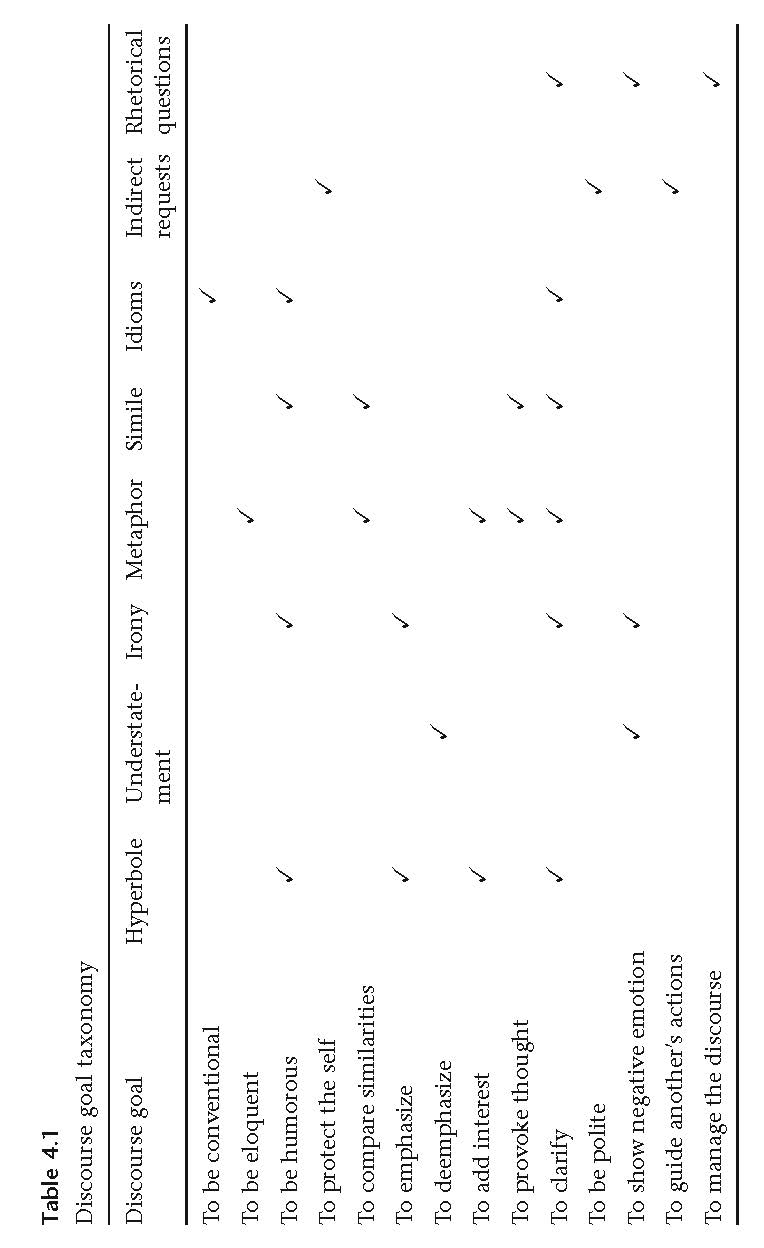

In a paper entitled “Why Do People Use Figurative Language?” we reported many reasons why English speakers use different figures of speech (see table 4.1). This table shows that speakers who use figurative language can do much more with their speech than those who merely stick to literal statements.

Although these data are only specific to English, the point here is that it is imperative to learn about figurative language from the very beginning of any language study. Although learning to make literal statements is also important, avoiding figurative language will make your speech sound stilted. As a nonnative speaker of the language, you will first try to use figurative language the way it is used in your native culture. This can work to varying degrees, but by attempting to use figurative language early on, you will be building expertise in the social use of your target language, which will allow you to communicate more naturally, as well as to use this knowledge in a top-down way to learn even more about the language.

An example of a figure of speech that can be incorporated in foreign language learning almost immediately is the rhetorical question, which can be thought of as an insincere question. For example, a mother who asks “How many times must I tell you?” while scolding her child is not asking for an answer. In fact, answering the question will probably have the perlocutionary effect of making mom mad.

In many languages, the intonation for the words yes and no can be quickly changed to make a rhetorical question. This is true in English, yes? And of course, these types of rhetorical questions are very quickly taught and learned in most foreign language situations. Because using a rhetorical question adds an extra component to an otherwise straightforward literal statement, it accomplishes at least two conversational goals at once: making a statement and asking for agreement. In Korean, for example, one way of making a rhetorical question is as easy as adding “jyo” to the end of the root form of adjectives and verbs. This means that as English speakers learn Korean, when they learn how to say that something is pretty, or interesting, or complicated, they can also practice using these words in a more natural way than just making a literal statement (“It’s hot” versus “It’s hot, don’t you think?”)—thereby greatly increasing the number of situations that students of Korean can try out their newly learned vocabulary words on unsuspecting native speakers.

Let’s look at another figure of speech: idiomatic expressions. An idiom can be thought of as a “frozen” metaphor. That is, over time, the more a metaphor is used, the less malleable it becomes. Of course, the first time someone learning English encounters an idiomatic expression such as kick the bucket to mean “die,” it will seem novel.9 But if a student learning English treats the idiom as if it’s not frozen and mistakenly says kick the can to mean “die”, he will not be understood. Note that part of learning the idiom kick the bucket includes learning when and where to use it. It might be more appropriate to use in reference to a despised dictator but not a beloved relative.

Although, as we noted earlier, rote memorization is not a strength of the adult language learner, idiomatic expressions are well worth the effort to acquire. Because idiomatic expressions can be used in a variety of settings, taking the time to learn these expressions can really pay off. For example, the linguistic equivalent of we’re all in the same boat will be helpful in a large number of situations, making your linguistic output much more interesting than merely saying something like same same.

In addition, knowing idiomatic expressions will give you insight into the culture. For example, in Korean the equivalent of the expression pie in the sky can be translated as “a picture of a rice cake.” This idiomatic expression is quite easy to memorize in Korean, since students of Korean learn the word for rice cake early in their studies. The word for picture is also a basic vocabulary word. It takes virtually no cognitive effort to join these two previously learned vocabulary words into the idiomatic expression, and can be done quite early in the language learning process. Waiting to learn this idiom until much later deprives the student of an easy way to increase proficiency and show cultural awareness.

One of the frustrations of the adult foreign language learner is that it takes a long time before he or she begins speaking and sounding like an adult. All too often, adult language learners lament the fact that they sound like a three-year-old—or worse yet, envy the three-year-old her fluency. Improving the “metaphoric intelligence” of a foreign language learner not only leads to better communicative effectiveness, it also serves to reinforce pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammatical structures in a natural and sophisticated way, and highlights cultural norms that are essential to language use.10 It’s also nice to speak like a grown-up.

Don’t Be a Language Zombie

Although it is beyond the scope of this book to describe all of the ways in which language interacts with culture, the social use of language is more than just accomplishing goals; it also includes using the language to maintain interpersonal relationships.11 If you ignore this fact, all the esoteric vocabulary and sophisticated grammar in the world can’t save you from making some serious blunders.

For example, Americans are uncomfortable with silence in a way that people from many other cultures are not. And because Americans don’t like silence, they talk in order to fill it. Americans talk to strangers in elevators. They talk to people in line at the grocery store. They talk to the clerk at the grocery store. They talk to their seatmates on airplanes. They even feel the need to get in the last word by saying “Have a nice day” at the end of the most mundane interactions.

Americans have words to describe this kind of talk: “meaningless conversation,” “shooting the breeze,” “idle chitchat,” “or “passing the time.” And all this empty chatter works just fine—as long as the other person is aware of what is going on.

But all too often, Americans fail to recognize that this empty, silence-filling banter is not always meaningless to non-Americans. At best, exchanging pleasantries with perfect strangers in another country will be seen as quaint or quintessentially American. Unfortunately, it may also lead them to think of Americans as rude, overly forward, or insincere; in many cultures, unlike the United States, any conversation—regardless of length or content—implies an attempt at establishing intimacy or closeness.

For example, two Americans can sit next to each other on a flight from New York to San Francisco and for the next five hours share secrets they wouldn’t tell their therapists. But when they get off the plane in San Francisco, they may not know each other’s names. And because they are Americans, not seeing each other again would feel perfectly natural, and possibly even desirable.

But if an American sits next to someone from another country, and chats pleasantly with him throughout the flight, it is possible that, by the time the plane lands, the non-American will want to figure out when they can meet again. This is because what seemed like idle conversation to the American was seen by the non-American as a sincere desire to establish a closer bond. And if the American doesn’t try to maintain the relationship, she might be viewed as superficial or phony. But of course, at the beginning of the flight, if the non-American didn’t respond to the American’s overtures at idle chitchat, he might be viewed as rude, cold, or standoffish.

As this example shows, interpersonal abilities that are finely tuned to one culture do not necessarily translate fully to another. Some adjustment is usually required. A convenient way to think about cultural differences that influence language use is to consider whether a culture is a high-context culture or a low-context culture.12

High-context cultures include Japan, China, and Korea. With regard to pragmatics, individuals from high-context cultures leave many things unsaid, since virtually all speakers of the language share the same cultural context.13 Put another way, since there is so much overlapping common ground among the speakers in a high-context culture, it is redundant, ridiculous, or rude to point out the obvious. Speakers from high-context cultures speak sparingly, therefore, using silence to convey meaning. Such a speech style sets up an “in group” versus an “out group” linguistic environment. For example, in Japanese, Korean, and Chinese a common term for foreigner directly translates as “outside country person.” Furthermore, Koreans so routinely refer to Korea as “our country,” that when Americans similarly try to refer to the US as “our country,” they are often misunderstood as also meaning Korea.

On the other hand, individuals from low-context cultures, such as Germany, Norway, and the US, cannot assume much overlap in the common ground of other speakers of the same language. Therefore, background information must be made explicit. Interestingly, one reason schizophrenic language is considered incoherent is because people with schizophrenia often fail to take into consideration the common ground that is shared between themselves and their conversational partners. Schizophrenic language generally becomes more intelligible as those with schizophrenia and their conversational partners spend more time together, which presumably happens because common ground is increasing.14

Of course, we are speaking here in broad generalities, since describing a culture as being high context or low context in no way describes all of the people in that culture. Nevertheless, adult language learners from a low-context, or relatively low-context, culture must make adjustments to their interpersonal style when they move to a higher-context culture. They must be prepared for the fact that much background information will be implicit, that their use of the language makes them an outsider, and that they may be considered rude if they ask too many questions or try to get to the bottom of an issue. Likewise, moving from one high-context culture to another high-context culture also requires adjustment, since important contextual cues that go unsaid will differ between the two high-context cultures. Perhaps only when one moves from one low-context culture to another low-context culture is there less of a requirement for any pragmatic adjustment. In this case, the two linguistic environments match in that both require substantial amounts of background information to be made explicit.

Of course, there are bound to be personal differences in adaptation to a new culture. One way to increase adjustment may be to seek out cultural contexts that match one’s personality. Expatriates whose personal characteristics match the predominant personality type of a target culture show better adjustment than those whose personalities do not match. For example, on average, people in Turkey are more extroverted than people in Japan.15 This suggests that an introvert might adjust better to living in Japan than in Turkey.

What does all this mean for learning a new language? It may seem odd, but as you speak your target language, you are creating a lens through which others will view you. In other words, others can’t separate “you” from “you speaking your target language.” Even the world-renowned author Mark Twain, when he went to Germany, found that he had created a separate identity for himself as a German speaker, and wrote about it to comic effect in his essay The Awful German Language.

Your goal, therefore, should be to create for yourself a linguistic competency that takes into account your own unique relationship to the target language and culture.16 The goal is not to mimic native speakers, but to express yourself as best you can while maintaining an identity apart from the target culture. If you don’t do this, then you may be viewed as attempting to pass yourself off as a native speaker, which others may find laughable at best and offensive at worst. The onus is on you, therefore, to make any needed cultural adjustments through your use of the language. In other words, foreign language learners should make pragmatic choices consistent with who they are in the cultural context rather than duplicate precisely the pragmatic choices of native speakers. It is entirely possible that mimicking native speakers’ pragmatic use of the language will lead to alienation.

In a similar way, cognitive scientists who study artificial intelligence have noticed that people find it disquieting when a robot’s appearance matches that of humans too closely. This phenomenon is known as the uncanny valley, because graphs that plot emotional responses to a robot’s appearance show a marked dip in how comfortable people are with robots that are almost, but not completely, lifelike.17 This drop in comfort level is similar to that of people’s repulsion to corpses and zombies. The goal of pragmatic mastery, therefore, should be not to impersonate a native speaker. You don’t want to be accused of being a language zombie.

As we hope these examples have shown, an adult language learner’s superior metapragmatic skills are more important than correctly conjugating an irregular verb or remembering an obscure vocabulary word. Don’t make the mistake of not capitalizing on the interpersonal skills you’ve honed over a lifetime in learning a new language and culture.