YOU DIDN’T NEED A CLAIRVOYANT to predict the burgeoning value of New York Central stock, but that didn’t stop Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennie C. Claflin. Both sisters claimed the ability to see visions of future events, a distinct advantage for a Wall Street broker (and one that gave a whole new dimension to Marshall McLuhan’s maxim about the medium being the message). One investor later testified that when she asked his advice about stock purchases, Vanderbilt himself replied, “Why don’t you do as I do, and consult the spirits?” Woodhull and Claflin (whom Vanderbilt proposed to marry) apparently found their inspiration, instead, from a less evanescent source, one with a proven track record. When they opened their brokerage business on January 22, 1870, on Broad Street, a portrait of Cornelius Vanderbilt prominently adorned one wall.

Five days later, on January 27, 1870, the spirits were willing. Vanderbilt presided over the first stockholders’ meeting of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, capitalized at a dazzling $90 million. Three months later, the company paid a $3.6 million semiannual 4 percent dividend, which the Times breathlessly pronounced “the very largest single dividend ever paid in this country by any one great corporation or state.” The New York Central was no ordinary corporation and its president was no ordinary man. “The creation of the New York Central & Hudson River stands as a historical landmark,” T.J. Stiles wrote, “showing us where the era of big business—the Vanderbilt era—well and truly began.”

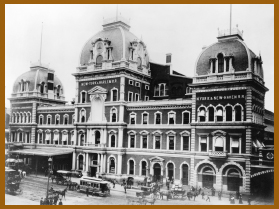

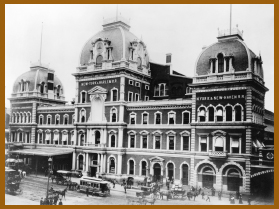

VANDERBILT INAUGURATED HIS ERA by introducing two customs borrowed from British railroads: every employee wore a uniform, and tickets were punched before passengers boarded their trains. But a great railroad required a great station of its own, so he built Grand Central Depot. It stretched 249 feet wide on East 42nd Street and north to East 48th Street. Some of the land on which it stood was already owned by the railroad and was used for storing cars and as a “fuel factory,” where a treadmill powered by horses teased with a wisp of hay operated the machinery that cut wood to power the steam locomotives that ran north of 42nd Street. Horses still pulled the streetcars south of 42nd Street through the tunnel under what is now Park Avenue from 33rd to 41st Streets, which is still used by automobiles. (As late as the mid-1870s, the line’s stables on Fourth Avenue between 32nd and 33rd Streets could still accommodate 916 horses, and even that number was sometimes insufficient.)

The Commodore acquired the rest of the site, which was largely vacant or occupied by pastures and shanties, by negotiating with private landlords whom the 1850 General Railroad Law of New York State had placed under a crippling disadvantage: the railroads were empowered to appropriate property and let the courts appraise its value. When Peter Goelet, a member of the prominent real estate family, offered to lease Vanderbilt the block bounded by 46th and 47th Streets and Madison and Fourth Avenues, the self-confident Commodore replied, pointedly in the first person singular: “I never lease property—always buy.” On November 1, 1871, less than two years after ground was broken, his $6.4 million depot and rail yard opened for business.

The land and construction cost well over $100 million in today’s dollars, and Vanderbilt, who was 78 when it was completed, paid for the depot out of his own deep pockets. It was later revealed, however, that because he was well versed in the ways and means of Tammany Hall, the transaction inevitably involved politicians’ pockets too.

A pair of court-appointed commissioners handed him Fourth Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets for a fire-sale price of $25,000 when the market price was closer to $350,000. Favoritism? Consider that just a year or two earlier, one of the Tweed ring’s Supreme Court justices had gone so far as to issue an arrest warrant for Jay Gould when he sought to prevent Vanderbilt from seizing control of the Erie Railroad. But perhaps the commissioners were unaware that the ring was no longer beholden to Vanderbilt, having undoubtedly succumbed to a better offer. So when the commissioners delivered Vanderbilt a bargain for the Fourth Avenue parcel in 1869, even Justice Albert Cardozo (the Tammany tool, whose son, the eminent jurist Benjamin Cardozo, proved how far an apple can fall from the tree) concluded that the deal was a sham that would “operate unjustly” to the city.

George Templeton Strong’s unvarnished review of the Commodore’s statue downtown might have been why Vanderbilt scrapped plans for a second such likeness. The Times said that another figure of the Commodore, this one also commissioned by his friend De Groot, weighing in at a half ton and flanked by a sailor and an Indian, was destined for the new passenger depot. Indeed, John B. Snook’s new American Second Empire–style building, clad in red pressed brick and cast-iron trim, left a huge niche at the third floor. “But the niche remained empty,” Christopher Gray later wrote in the Times—“perhaps the earlier japes had convinced Vanderbilt of the virtues of modesty.” (Shortly after the opening of Grand Central, the Times took him to task over repeated accidents in the open railroad yards to the north, saying that any tribute in bronze should also include “the dismembered bodies of men, women and children.”) The original massive statue of the Commodore finally came home to the viaduct around the south façade of Grand Central Terminal in 1929, where it still stands. “For now,” Gray wrote, “he stands a hostage, in a haze of exhaust produced by the railroad’s most potent enemy, the automobile.”

John B. Snook’s architectural imprint endures on the nation’s first department store, A.T. Stewart’s at 280 Broadway, and the cast-iron façades in what is now SoHo. Vanderbilt’s depot was billed as the nation’s biggest railroad station and, by one measure, was even larger than the world’s biggest, London’s Victorian St. Pancras, which had opened three years earlier. The imposing three-story building that fronted on 42nd Street was inspired by the palace of Versailles and the Tuileries. It rivaled the Eiffel Tower and Crystal Palace for its ingenious engineering, if not its grandeur. (It was largely overlooked on opening day, though; the New York newspapers were preoccupied by the Great Chicago Fire the night before.)

The depot was distinguished by five mansard roofs. But its most memorable architectural feature was a 652-foot-long arch-ribbed-vault train shed that was modeled on St. Pancras. Thirty-one iron trusses supported the depot’s resplendent 60,000-square-foot semicircular glass roof. The half-cylindrical ceiling was 200 feet wide and soared 100 feet at its apex—the largest interior space on the North American continent and second as a tourist attraction only to the Capitol in Washington.

The effect was magical. It sparked the imagination of novelists. The depot was where Richard Harding Davis’s Captain Royal Macklin, returning from his escapade in Honduras, reveled in buying a train ticket to his hometown in Dobbs Ferry. It was also there, in the afternoon rush one September in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, that Lawrence Selden began his stroll with Lily Bart—“a figure to arrest even the suburban traveler rushing to his last train. Against the dull tints of the crowd,” Wharton wrote, her vivid head “made her more conspicuous than in a ballroom” as she threaded “through the throng of returning holiday-makers, past sallow-faced girls in preposterous hats, and flat-chested women struggling with paper bundles and palm-leaf fans.”

The old station on 26th Street was sold to P.T. Barnum, who converted it into the Hippodrome, a showcase for circuses and other spectacles. In 1879, it was taken over by the Commodore’s grandson, who renamed it Madison Square Garden. (The name endured four incarnations; the second one was where Harry K. Thaw, jealous over the alienation of his affection for Evelyn Nesbit, shot Stanford White in 1906 in a jealous rage; years later, after visiting the South Florida Mediterranean revival hotels, clubs, and mansions designed by Addison Mizner, Thaw lamented: “I shot the wrong architect.” Well, everyone’s a critic.) “Without much pretension to architectural elegance,” a professional critic wrote of the new depot, “it is commodious and well adapted to the purposes for which it was designed, and perhaps we ought not to ask much more from a railroad depot.”

The Times carped, though, that the depot “can only by a stretch of courtesy be called either central or grand”—particularly because 42nd Street was by no means the center of New York City yet. The remote depot was derided by another journal as “End of the World Station.” The critic Lewis Mumford would later denigrate its “imperial façade.” More than a century later, Christopher Gray would write in the Times that the station was “awkwardly up-to-the-minute, more cowtown than continental.”

For reasons that were never made clear, Vanderbilt gave his tenant the New Haven the prime location, fronting East 42nd Street. The Harlem and the Central were relegated to Vanderbilt Avenue. Also lost to history was the reasoning behind the arrangement of the tracks. Because outbound trains left from the west side of the train shed and inbound arrived on the east side, trains had to cross each other’s paths, which they did first at 53rd Street and later at Spuyten Duyvil along the Harlem River and Woodlawn in the north Bronx. Even with five platforms and 15 tracks, passengers complained that they were jammed waiting at entrances for the 88 daily trains and resented the long hike to the platforms.

FOR SOME REASON, THE NEW HAVEN, WHICH WAS MERELY A TENANT, ENJOYED THE MOST PROMINENT FAÇADE, ON EAST 42ND STREET.

Each of the three railroads served by the depot had a separate waiting room, creating havoc for baggage-laden passengers transferring from one line to another and mingling long-distance travelers and commuters. Because the depot was in the middle of nowhere, passengers were “penned in like hogs” on the streetcars that ferried them from the depot to downtown. They were so crowded that the wait to board a commodious car could easily last an hour. The trip to City Hall, still the center of New York, could take another hour. “Without a single exception,” the Times reported in 1871, New Yorkers “denounced the administration of affairs, not only in regard to the slow and wretched arrangement of time on the horse-cars, but also the inconveniences and outrages suffered by passengers at the Grand Central Depot.” Dennis McMahon of Morrisania in the Bronx groused that he could get from the old station on 26th Street to Chambers Street in lower Manhattan in 25 minutes. The railroad promised that the new depot would save him seven minutes, but instead, “Now I never reckon on less than an hour.” Complaining that “we lose one hour between the depot and City Hall,” C.W. Poole of Mount Vernon invoked the ultimate threat, to “sell out and move to New Jersey.”

The train shed itself was remarkably quiet and free of smoke, however. Ringing bells and blowing whistles were banned, and railroad cars minus locomotives coasted to the platforms by gravity. The Herald proclaimed it “the finest passenger railroad depot in the world,” and it would play a vital role not only as a transportation hub, but also in the early development of Midtown. That development included the Vanderbilt mansions that the Commodore’s children and grandchildren built for themselves on Fifth Avenue, prompting Edith Wharton to lament that their extravagances thoroughly retarded culture and confined them to a narrow corridor that conjured up the coastal passage in ancient Greece. “They are entrenched in a sort of Thermopylae of bad taste, from which apparently no force on earth can dislodge them,” she wrote.

When the Commodore died in 1877, he left nearly his entire fortune to William H., the son he trusted most. Within a few years, William’s wealth more than doubled. William’s sons, William K. and Cornelius II, would build Marble House and the Breakers, respectively, in Newport, Rhode Island. Their grandfather died on January 4, as were falling the first flakes of a blizzard that would shatter the glass roof of the Grand Central Depot. In total, the Commodore left $100 million—more money than was held by the U.S. Treasury. “Any fool can make a fortune,” he once said. “It takes a man of brains to hold on to it after it is made.” His last words were “keep the money together”—an admonition that went unheeded by his heirs.

“With the death of Cornelius II in 1899 at the age of only 56, the Vanderbilt dynasty at the New York Central really came to an end,” Louis Auchincloss concluded, although Vanderbilt great-grandsons would remain involved with the railroad until the 1950s. “The 10 Vanderbilt mansions that once lined Fifth Avenue were never occupied by the next generation,” Arthur T. Vanderbilt II wrote in Fortune’s Children. “One by one, they fell to the wrecker’s ball, their contest lost to the auctioneer’s gavel.” Only the grand depot and its glorious successor would endure as their legacy.