HAD THERE BEEN ANY DOUBTS about the depot’s adequacy even after the renovations, two events dispelled them as the new century began. The fatal crash in the Grand Central yards prompted demands that the engineer and even the New York Central’s management be prosecuted for manslaughter and suggestions that the railroad be barred from Manhattan altogether and required to build a new terminus at its Mott Haven yards in the South Bronx instead. A month earlier, another event proved just as decisive: the Pennsylvania Railroad, the New York Central’s chief competitor to points west, announced that it would challenge the Central’s Manhattan monopoly by tunneling under the Hudson River from New Jersey and building a sumptuous station on the West Side.

As the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad’s chief engineer since 1899, William J. Wilgus had supervised the recent costly renovation of Grand Central. Born in Buffalo in 1865, Wilgus studied for two years under a local civil engineer and later took a Cornell correspondence course in drafting. His creativity and expertise propelled him through the ranks of various railroads and finally to the New York Central. The fatal 1902 crash persuaded him that the renovations, as impressive as they were, were insufficient to stem the rising tide of public outrage over the preposterous notion of running a chaotic railroad yard in what a few decades earlier had been a practically bucolic landscape but by now was becoming the very heart of the nation’s largest city.

JOHN M. WISKER, ACCUSED OF CAUSING THE 1902 CRASH.

Already, prompted by the 1902 crash, the state legislature had extended the ban on steam-powered locomotives from 42nd Street all the way to the Harlem River, effective 1908 (imposing a $500-a-day fine unless the mayor “shall certify to the necessity for the use of steam locomotives arising from the temporary failure of other motive power”). Railroad officials briefly considered diverting commuter traffic to a “Grand Union Station” on the Harlem River in the Bronx, which would be accessible by subways and elevated trains. But Wilgus conceived another alternative.

“Suddenly, there came a flash of light,” he recalled decades later. “It was the most daring idea that ever occurred to me.” In a succinct three-page letter to W.H. Newman, the railroad’s president, dated December 22, 1902, less than a year after the crash, the 37-year-old self-taught chief engineer recommended an audacious and extravagant remedy: raze the new Grand Central Station that had just been renovated and replace the egregious steam locomotives with electric trains, which had advanced technologically since they were first introduced on a main line by the Baltimore & Ohio in 1895 (four years later Wilgus himself had proposed an experimental trial on the Central; his plan was adopted but not implemented).

The technological advantages were clear-cut. Electricity required less maintenance. Unlike steam or, later, diesel locomotives, electric trains did not need the fuel or machinery to generate power on board. Electricity empowered trains to accelerate more quickly, a decided amenity for short-haul commuter service. Another advantage, an obvious one, in retrospect, provided the rationale that made Wilgus’s suggestion so revolutionary and, in the end, so inevitable. Electric motors produced fewer noxious fumes and no obfuscating smoke or steam. That would help quell the public outcry and quiet the increasing vocal critics who regarded the trains as a necessary evil, one that was needlessly dangerous and inconvenient, though. Moreover, as Wilgus explained, electricity “dispenses with the need of old-style train sheds,” because it made subterranean tracks feasible.

WILLIAM J. WILGUS, THE CENTRAL’S CHIEF ENGINEER.

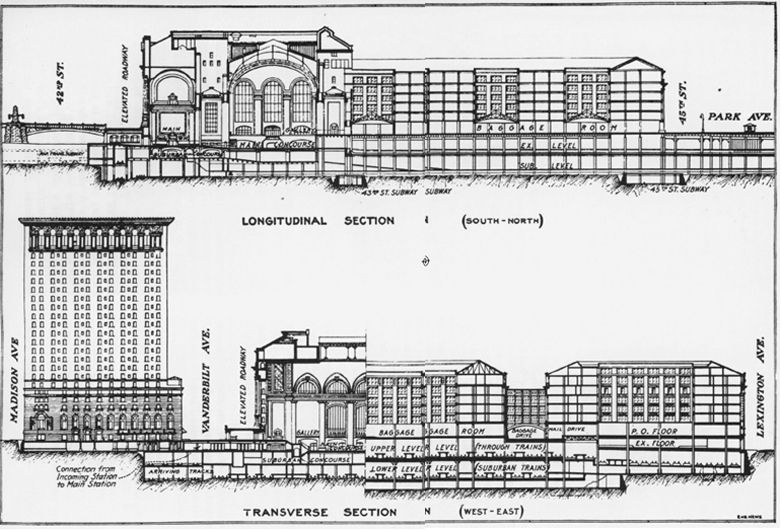

Absent the smothering smoke, soot, and cinders, the depot could be expanded on the same footprint by delivering trains to platforms on two levels, the lower for suburban commuters and the upper for long-distance trains. For the first time, the entire rail yard all the way to 56th Street, to where the maze of rails that delivered passengers to the platforms coalesced into four main-line tracks, could be decked over. The “veritable ‘Chinese Wall’ ” that bisected the city for 14 blocks could be eliminated. The air above the yards could be magically transformed into valuable real estate in the heart of Manhattan.

For starters, Wilgus envisioned a 12-story, 2.3-million-square-foot building above the terminal that could generate rents totaling $2.3 million annually. Those advantages not only benefited “humanity in general,” as the Commodore would have put it, an ingratiating by-product, but also fulfilled the railroad’s primary mission that “we first see that we are benefiting ourselves.” Wilgus’s overarching remedy to the “Park Avenue problem,” he unabashedly proclaimed, “marked the opening of a remarkable opportunity for the accomplishment of a public good with considerations of private gain in behalf of the corporation involved.”

“History,” James Marston Fitch and Diana S. Waite wrote, “was to prove this an epochal scheme.”

IF WILGUS DID NOT INVENT the notion of air rights and rivet the principle into real estate law, he surely applied it on a larger scale than anyone had ever imagined. “Thus from the air would be taken wealth with which to finance obligatory vast changes otherwise nonproductive,” he said. And by capitalizing on those rights, rights to build towering hotels and office buildings and private clubs that just happened to have trains coursing through their subbasements, the railroad would reap enough revenue to recoup the costs of electrification. The terminal, he explained later, “could be transformed from a non-productive agency of transportation to a self-contained producer of revenue—a gold mine so to speak.”

In 1902, with the sprawling yards still flanked by pastures for an occasional cow or goat and by cheap tenements proliferating farther east, it would take a stubborn visionary to recognize that this blighted swath of Midtown could be converted into an iconic 140-foot-wide canyon bordered by brick, steel, and glass skyscrapers (and, in name, at least, join the stretches in Murray Hill, below 42nd Street, which had earlier been christened Park Avenue).

Wilgus envisioned other innovations: constructing an elevated roadway that would gird the terminal and no longer render it a roadblock in the middle of Park Avenue; reserving the upper level of the terminal for long-distance trains and the lower for the growing number of commuters; building loops on both levels, which would allow trains to turn around instead of wasting time backing out; and installing ramps that would obviate the struggle up and down stairs for passengers with baggage.

Years later, Wilgus would recall that his letter to President Newman got mixed reviews. “At first, he properly questioned the practicability of the scheme,” the engineer recalled.

He felt that the office space would be a place only “for birds to roost”; that the proposed hotel on the vacant square bounded by Madison Avenue, 43rd and 44th Streets and Vanderbilt Avenue, would be as unpopular as railroad hotels in Europe; that hansom cab-men could not be driven to use Madison Avenue because of their addiction to the sights of Fifth Avenue; and that underground horse cab-stands would be repulsive because of odors. My counter-arguments were that the rapidly increasing demand for office space in the vicinity would surely bring us tenants; that the use of electricity would obviate the features that made the European railroad hotels unpopular; that growing congestion would cause the cab-man to gladly avail himself of the new thoroughfares; and that the coming of the motor-car, then in its infancy, instead of the horse-drawn vehicle would obviate objectionable odors. It was also necessary to urge counter-arguments against the allegations of those who were not friendly to ramps in place of stairways and who opposed what they termed the “grocery store” idea of lending the station to revenue producing purposes.

Wilgus was asking the railroad’s directors to accept a great deal on faith. His projected $35 million price tag for all the improvements, including a conservative estimate for electrification, nearly equaled half the railroad’s revenue for a full year. Moreover, the railroad made most of its money hauling freight, not people. Why invest so much in a project that benefited only passengers? But the chief engineer was persuasive. He delivered his proposal on December 22, 1902. By January 10, the Central’s board of directors had embraced the project and promoted him. Six months later, on June 30, 1903, the board—whose directors included the Commodore’s grandsons, Cornelius II and William K. Vanderbilt, William Rockefeller, and J.P. Morgan—in a daring validation of the chief engineer’s vision, formally empowered Wilgus to proceed with his bold agenda for a regal terminal that would be a gateway to the continent.

Once he was given the go-ahead, Wilgus still faced two daunting challenges: how to electrify the railroad (and how much of it to electrify); and how to build a new terminal and raze the old one without disrupting passenger traffic. He approached both quandaries with characteristic bravado. Rather than adhere narrowly to the mandate imposed by the state—to ban steam locomotives in Manhattan—Wilgus proposed to electrify the railroad the full 23 miles to White Plains on the Harlem line and all 33 miles to Croton on the Hudson line.

He gave two compelling reasons. One was that commuters accounted for a growing proportion of the railroad’s passenger traffic and they would be reluctant to waste time transferring in the Bronx to steam locomotives. Moreover, as noted, electric motors allowed trains to accelerate more quickly than steam locomotives, a big advantage for commuter railroads that hopscotched between suburban stations. Theoretically, what Wilgus was proposing seemed sensible, and the decision, as he later described it, was “inescapable.” But translating his hypotheses about the technological and commercial advantages of electricity into dependable motive power was something else altogether.

“No existing railroad electrification anywhere in the world,” Kurt C. Schlichting wrote in his biography of Wilgus, “approached the scale of the Central’s project or provided a model to duplicate.”

AN ELECTRIC TRACTION ENGINE had made its experimental debut on the Ninth Avenue El in New York as early as 1885, but the sparks it generated and its slow speed doomed it for the time being. Using electricity to power trains over long distances was relatively untested. In 1897, Frank J. Sprague, an acolyte of Thomas Edison’s, adapted an innovative device he had invented for elevators to railroad cars, allowing them to operate in tandem, each with its own electric motor.

THE SHOTGUN MARRIAGE OF ARCHITECTURAL FIRMS YIELDED A GRAND DESIGN GREATER THAN THE SUM OF THEIR SEPARATE BLUEPRINTS.

Sprague approached the Central’s directors with his vision, but the imperatives of electrification were not yet apparent. Still unresolved, too, was how best to generate electricity—through direct current, which was produced at a particular voltage and delivered to the user at the same energy but loses power over long distances; or alternating current, in which the charge periodically shifts direction and the high voltage is reduced before delivery. Given the commercial stakes, as more and more big-city and commuter railroads bowed to government pressure and began to electrify, Wilgus’s dilemma sparked a reprise of the scientific debate a decade earlier over which version of current was most serviceable to execute felons condemned to death.

In 1890, Edison, an advocate of direct current, surreptitiously powered New York’s first electric chair with George Westinghouse’s alternating current, hoping to demonstrate that alternating current was generally so lethal that it should be reserved only for inflicting capital punishment. Edison proved his point: William Kemmler, a convicted killer, was executed (more or less successfully). The debate didn’t end there, though. Westinghouse and Sprague angrily waged a war of words in the pages of the Railroad Gazette.

Eventually, Edison and Sprague carried the day. The New York Central, following the lead of the Baltimore & Ohio, opted for direct current traveling through a third rail that delivered power to each railroad car through a spring-loaded “shoe” extending from the motor. (Unlike the New York City subway system and the Long Island Rail Road, Metro-North trains now draw power from the underside of the third rail, which allows for insulation above to prevent electrocution and icing.)

In 1906, well in advance of the state-imposed deadline for electrification, the Central began operating electric cars from Grand Central. (The New Haven followed suit a year later, using direct current from the Central’s third rail but switching to alternating current delivered from overhead lines on its own tracks in Connecticut, as it does today.)

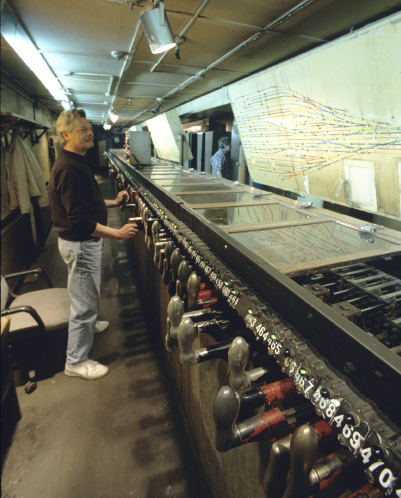

A HUNDRED SWITCHMEN, INCLUDING TIM COUGHLIN, MANAGED THE METRO-NORTH LINE. NOW A DOZEN RAIL TRAFFIC CONTROLLERS DO THE JOB.

ON JUNE 19, 1903, the city granted subsurface rights to the New York Central between Lexington and Madison Avenues and East 42nd and 47th Streets for $25,000 annually in perpetuity. Work in earnest began on August 17, 1903. Unlike the depot built three decades earlier, the new Grand Central would actually define “Midtown.” The center of the city had been inexorably advancing from downtown, mirroring the railroad’s own brand of manifest destiny. That advance had been nominally cemented on the West Side with the advent of the 25-story Times Tower at 42nd Street and Broadway, then the second-tallest building in the city, which was still under construction. On December 31, 1903, 200,000 spectators would accept the Times’ invitation to celebrate the new building and the New Year with a fireworks display from the roof at midnight (the ball drop down a flagpole on the roof would begin five years later).

The new Grand Central Terminal—and it would be a terminal, because New York Central horsecars would no longer ferry commuters from its train platforms to destinations downtown—would draw nearly as many people in a single day as Times Square did on New Year’s Eve. Grand Central was designed to accommodate even more, maybe even as many as 100 million a year by the beginning of the 21st century, when the terminal would celebrate its centennial.

Even before the first spadeful of earth was turned, before the first boulder of Manhattan schist was blasted, a veritable forest of exclamation points began sprouting with what was dubbed the city’s largest individual demolition contract ever. On 17 acres purchased by the railroad, 120 houses, three churches, two hospitals, and an orphan asylum would have to be obliterated, as would stables, warehouses, and other ancillary structures.

The Times admitted that “in describing it, the superlative degree must be kept in constant use.” It would be the biggest, it would contain the most trackage, and, on top of that, it would be self-supporting.

Once the method of motive power was agreed upon, Wilgus’s second challenge was how to build a terminal without inconveniencing the passengers on the railroad’s hundreds of daily long-haul and commuter trains. To meet the challenge, the railroad temporarily relocated some of the station’s functions to the nearby Grand Central Palace Hotel. Again Wilgus devised an ingenious construction strategy. The arduous process of demolishing existing structures, excavating rock and dirt 90 feet deep for the bilevel platforms and utilities, razing the mammoth train shed, and building the new terminal would proceed in longitudinal “bites,” as he called them—troughs bored through the middle of Manhattan, one section at a time and proceeding from east to west. Construction would take fully 10 years, and by the time it was barely halfway finished, Wilgus would be gone and his guesstimate of the cost of the project would have doubled to about $2 billion in today’s dollars.

JOHN WISKER, the man whose train accident in the Park Avenue Tunnel triggered the construction of Grand Central Terminal, did not live to see it completed. While no railroad officials were prosecuted, the accident sparked 30 lawsuits against the Central. One resulted in a record $60,000 jury verdict for the victim’s widow (about $1.5 million in current dollars). Another verdict won by a Bronx stenographer, $1,250 for personal injuries, was tossed out by a judge who concluded that the “victim” quite possibly had not been a passenger on either train.

At Wisker’s manslaughter trial, he was represented by Frank Moss (a dogged investigator who once provoked Richard Croker, the Tammany boss, to admit, “I am working for my pocket all the time, just like you, Mr. Moss”). On April 24, 1903, less than three months before ground was broken for the new Grand Central, the Manhattan jury delivered its verdict after only two hours of deliberations.

Wisker stood pale and trembling, according to contemporary accounts, “a shadow of the sturdy fellow who was arrested the day of the fatal collision.” He collapsed into his seat and cried when the foreman pronounced him not guilty. Wisker was, apparently, accident-prone, though. Seven years later, operating a hoist for a coal company on the West Side, he fell into the Hudson River and drowned.

AS CONSTRUCTION ON THE TERMINAL progressed, the New York Central was keeping one very wary eye on what was happening just across town. Its archrival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, was challenging the Central’s monopoly by finally providing direct service to Manhattan. The Central and the Pennsy were like Coke and Pepsi, perennial rivals for routes, passengers, and market share. The Pennsylvania was older (by name, at least) and bigger (by cargo tons carried), but the Central more than matched it in ego and glitz, as befitted their two home states. The Pennsylvania’s keystone logo evoked the keystone state. The Central’s was a distinctive, but not evocative oval. New York was in the name. Anything else was superfluous,

In the 19th century, the Pennsylvania was an also-ran in New York City. Without a Midtown station, passengers had to be ferried between Exchange Place in Jersey City and Manhattan by boat. Building a bridge across the river would have required a joint project with other Jersey railroads, but none was game. Electrification, though, would make a Hudson River tunnel feasible. On December 12, 1901, a little less than a month before the Park Avenue Tunnel crash, Alexander Cassatt, the Pennsylvania’s president, announced that the railroad would bore under the river and run trains to a grand station of its own to be built on two square blocks bounded by 31st and 33rd Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues.

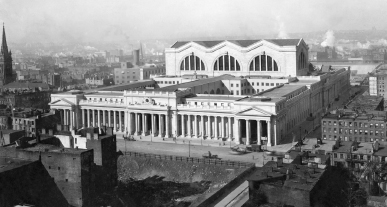

PENN STATION CHALLENGED THE NEW YORK CENTRAL’S MANHATTAN MONOPOLY.

Ground was broken on May 1, 1904, for McKim, Mead & White’s colossal gateway. The breathtaking pink-granite-colonnaded station—a “great Doric temple to transportation,” the historian Jill Jonnes called it—was modeled on the public baths built in Rome 1,700 years earlier by Emperor Caracalla. It spanned seven acres and sat astride the tracks that continued under the East River to connect with the Long Island Rail Road and the Pennsylvania’s Sunnyside Yards in Queens. The station would open in 1910 and, with the expense of the two sets of tunnels, cost $114 million, or about $2.7 billion in today’s dollars. And if, by some measures, it was a bigger station than the proposed Grand Central, the New York Central’s publicity department wasted no time in pronouncing its new depot the biggest terminal in the world. Despite its stark grandeur of girders and glass, Penn Station would never become the catalyst for planned development that Grand Central did.

WILLIAM WILGUS WAS AN ENGINEER, not an architect, but he hoped to impose his own aesthetic on the new terminal. He knew what he didn’t like about the old depot: its “unattractive architectural design” and its “unfortunate exterior color treatment,” as well as the “great blunder” of dividing the city for 14 blocks and by obstructing Fourth Avenue. Once he persuaded the Vanderbilts and the Central’s other directors to accept his bold vision, they were intent on not repeating earlier mistakes, which had cost not only money, but goodwill as well.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE TERMINAL TOOK 10 YEARS. MORE THAN 150,000 PEOPLE SHOWED UP FOR THE OFFICIAL OPENING ON FEBRUARY 2, 1913.

In 1903, the Central invited the nation’s leading architects to submit designs for the new terminal. Samuel Huckel Jr. went for baroque, a turreted confection with Park Avenue slicing through it. McKim, Mead & White proposed a 60-story skyscraper—the world’s tallest—atop the terminal (a modified version was later incorporated into the firm’s design for the 26-story Municipal Building, completed in 1916), itself topped by a dramatic 300-foot jet of steam illuminated in red as a beacon for ships and an advertisement (if, even then, an anachronistic one) for the railroad.

Reed & Stem, a St. Paul firm (the name evoked landscape architects), won the competition. (Its successor, WASA/Studio A, still operates in New York City.) The firm began with two big advantages. It had designed other stations for the New York Central. Moreover, like the Central itself, Reed & Stem could count on connections: Allen H. Stem was Wilgus’s brother-in-law. Yet in the highly charged world of real estate development in New York, another firm’s connections trumped Reed & Stem’s. After the selection was announced, Warren & Wetmore, who were architects of the New York Yacht Club and who boasted society connections, submitted an alternative design. It didn’t hurt that Whitney Warren was William Vanderbilt’s cousin.

The Central’s chairman officiated at a shotgun marriage of the two firms, pronouncing them the Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal. The partnership would be fraught with dissension, design changes, and acrimony and would climax two decades later in a spectacular lawsuit and an appropriately monumental settlement. In 1921, a referee found that Warren’s accounting was “improper and erroneous” and awarded Stem, the surviving partner, the fantastic sum of $223,891.16—in effect validating Warren’s maxim that “the standard of success in this country is the making of money, therefore, the architect should make money and be considered successful.”

To Wilgus’s dismay, the Warren & Wetmore version eliminated the revenue-generating office and hotel tower atop the terminal. It also scrapped the vehicular viaducts that would remedy the obstruction of Fourth Avenue created by the depot. (Some aspects of the original Reed & Stem design would later be restored.) But by any measure, the new terminal would justify its name. It would be grand.

Once the design was agreed upon, building Grand Central was a gargantuan undertaking. Wheezing steam shovels excavated nearly 3.2 million cubic yards of earth and rock to an average depth of 45 feet to accommodate the subterranean train yards, bilevel platforms, and utilities—some as deep as 10 stories. The daily detritus, coupled with debris from the demolition of the old station, amounted to 1,000 cubic yards and filled nearly 300 railway dump cars. The lower tracks were 40 feet below street level and sprouted “a submerged forest” of steel girders. Construction required 118,597 tons of steel to create the superstructure and 33 miles of track. At peak construction periods, 10,000 workers were assigned to the site and work progressed around the clock. Beneath the 770-foot-wide valley he created in Midtown Manhattan, Wilgus dug a six-foot-diameter drainage sewer about 65 feet deep that ran a half mile to the East River.

THE CENTRAL NOT ONLY MET the state’s deadline to electrify the line in Manhattan, but did so two years early. The route was electrified for 17 miles, north to Wakefield and Kingsbridge in the Bronx. The first electric locomotive barreled through the Park Avenue Tunnel from High Bridge on September 30, 1906. Thirty-five 2,200-horsepower electric locomotives could accelerate to 40 mph; multiple-unit suburban trains could hit 52 mph. The Vanderbilts and the New York Central were immensely proud of their all-electric terminal and their mostly electric railroad. The maze of tracks and trains was commanded from a four-story switch-and-signal tower below 50th Street. On one floor was a machine with 400 levers, the largest ever constructed, to sort out the suburban trains. On the floor above, another machine with 362 levers controlled the express tracks. A worker was assigned to each battery of 40 levers, and tiny bulbs on a facsimile of the train yard would automatically be extinguished as a train passed a switch and illuminated again when it reached the next switch.

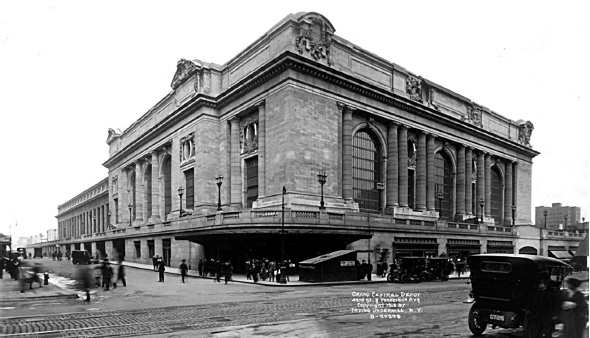

THE COMPLETED TERMINAL WAS ORIGINALLY A SOLITARY PRESENCE ON EAST 42ND STREET, BUT NOT FOR LONG. DEVELOPMENT SPREAD EAST.

On June 5, 1910, the Owl, as the midnight train was known, left Grand Central Station for Boston. It was the last to depart from the old depot, which handled an impressive 100 trains a day when it opened but was incapable of servicing the hundreds of trains that arrived and departed daily four decades later. Demolition began immediately. The old station and yards spanned a little more than 23 acres. The new one covered more than twice that area. The station had a capacity of 366 railway cars. The new terminal could accommodate 1,053. The old depot handled 9,000 suitcases and trunks a day. The new one could handle 16,000 pieces of luggage.

WHILE PENNSYLVANIA STATION opened earlier and to rave reviews, it could not compare to Grand Central in magnitude. Penn Station and its yards spanned 28 acres. Grand Central covered 70. Penn Station had 16 miles of rails that converged into 21 tracks serving 11 platforms. The comparable figures for Grand Central originally were 32 miles, 46 tracks, and 30 platforms. Grand Central required twice as much masonry and nearly twice the steel that Penn Station did. Fifteen hundred columns were installed to support the street-level deck and the buildings that would rise on it. Another $800,000 was spent on steel reinforcement, not needed for the terminal itself, but to support a skyscraper that eventually might rise above it. The terminal alone cost $43 million to build, the equivalent of about $1 billion today, and the entire project set the Central back about $80 million.

Passengers’ comfort was of paramount concern. When it was finally completed, Grand Central could boast a separate women’s waiting room with oak floors and wainscoting and maids at the ready; a ladies’ shoe-polishing room “out of sight of the rubbernecks” and staffed by “colored girls in neat blue liveries”; a telephone room for making calls; a salon gussied up with walls and ceilings of Carrara glass, “where none but her own sex will see while she has her hair dressed”; a dressing room attended by a maid (at 25 cents); and a private barber shop for men, which could be rented for $1 an hour, and a public version where “the customer may elect to be shaved in anyone of 30 languages.”

No amenity was spared. “Timid travelers may ask questions with no fear of being rebuffed by hurrying trainmen, or imposed upon by hotel runners, chauffeurs, or others in blue uniforms,” a promotional brochure boasted. Instead, “walking encyclopedias” in gray frock coats and white caps were available. Passengers would be protected from unwanted contact as well as glances. “Special accommodations are to be provided for immigrants and gangs of laborers,” the Times reported. “They can be brought into the station and enter a separate room without meeting other travelers.” Grand Central, the brochure proclaimed, is “a place where one delights to loiter, admiring its beauty and symmetrical lines—a poem in stone.”

JUST HOW MUCH LOITERING could have been done on opening day is arguable. Railroad officials estimated that by 4 p.m. on Sunday, February 2, 1913, more than 150,000 people had visited the terminal since the doors were thrown open at midnight. The first train to leave was the Boston Express No. 2, at 12:01 a.m. The first to arrive was a local on the Harlem line. F.M. Lahm of Yonkers bought the first ticket.

Grand Central was billed as the first great “stairless” station, one in which the flow of passengers was sped by gently sloping ramps that were tested out at various grades and ultimately designed to accommodate everyone from “the old, infirm traveler, to the little tot toddling along at his mother’s side, to the man laden down with baggage which he declines to relinquish to any one of the most cordial attendants, to the women trailing a long and preposterous train.” (Ramp—the very word was obscure, prompting Munsey’s magazine to explain to readers that Julius Caesar had built a long sloping earthworks to the ramparts when he laid siege to a city.) The flow would now empty from 32 Upper Level and 17 Lower Level platforms (fed from as many as 66 and 57 tracks, respectively) into a Main Concourse that was 275 feet long, 120 feet wide, and 125 feet high (spreading nearly 38,000 square feet) and flanked by 90-foot-high transparent walls that were punctuated by glass walkways connecting the terminal’s corner offices.

THE OYSTER BAR, HERE AROUND 1913, IS THE TERMINAL’S OLDEST TENANT. IT SELLS SOME 5 MILLION BIVALVES ANNUALLY AND RETAINS ITS ELEGANCE.

Its concave ceiling created a view of the heavens from Aquarius to Cancer in an October sky, 2,500 stars—59 of them illuminated and intersected by two broad golden bands representing the ecliptic and the equator. For several months, painters debated how to squeeze the heavens onto a cylindrical ceiling because the artist Paul Helleu’s version seemed more fitting for a dome and experimented to find just the proper shade of blue. (Helleu was no stranger to the Vanderbilts. Proceeds from his wildly popular 1901 sketch of Consuelo Vanderbilt, the American-born duchess of Marlborough and William K.’s daughter, had helped support his extravagant Belle Epoque lifestyle.)

The ceiling designs were developed by J. Monroe Hewlett and executed largely by Charles Basing and his associates. As many as 50 painters under Basing’s direction worked simultaneously to ensure that there was no differentiation in color tone. Lunette windows were ornamented with plaster reliefs of winged locomotive wheels, branches of foliage symbolizing transportation, and clouds and a caduceus (the short staff usually entwined with serpents and surrounded by wings and typically carried by heralds).

The finishing touches would not be complete for another year (the viaduct would not be opened until 1919 and the innovative Lower Level loop, which allowed arriving trains to depart more quickly, would not become operational until 1927). Among the last was the gigantic sculpture designed by a Frenchman, Jules Félix Coutan, above the central portal on 42nd Street. Coutan, who also designed the France of the Renaissance sculpture for the extravagant Alexander III bridge in Paris, created a one-fourth-size plaster model in his studio from which John Donnelly, a native of Ireland, carved the final 1,500-ton version from Indiana limestone at the William Bradley & Son yards in Long Island City, Queens. (Donnelly also worked on Riverside Church and the U.S. Courthouse in Manhattan and the Supreme Court Building in Washington.)

The railroad described Transportation, the 60-foot-wide, 50-foot-tall sculpture, considered at the time the world’s largest sculptured group, as representing “Progress, Mental and Physical Force,” with Hercules embodying physical strength, the reclining Minerva wisdom and the arts, and Mercury, wearing a winged helmet and protected by a vigilant American eagle, science and commerce as the messenger of the gods. (Some second-guessers say Hercules is really Vulcan, the blacksmith, holding a hammer and emblematic of the iron horse. Also, while Whitney Warren interpreted the trio as mental and moral energy supporting the glory of commerce, a Metro-North guidebook demythologized the impact and attributed it to mental and mortal energy.)

“The three were meant to symbolize the grandeur of the Vanderbilts’ New York Central Railroad, but surely these are the tutelary deities of all Manhattan, the city of the unquenchable entrepreneurial flame,” the architectural historian Francis Morrone wrote. “As the historian Paul Johnson reminds us… so-called robber barons such as the Vanderbilts, ruthless though they undoubtedly were, not only left magnificent monuments in their wake but also created the vast national enterprises into which the teeming multitudes of immigrants were absorbed and uplifted by the engine of prosperity. To deny that this is what New York, in its essence, is about is to posit a fantasy city.”

Contemplating a plaster model of the sculpture in his office, Warren later wrote that while the ancients entered cities through triumphal gates that punctuated mighty fortifications, in New York and other cities the gateway is more likely to be “a tunnel which discharges the human flow in the very center of the town. Such is the Grand Central Terminal and the motive of its façade is an attempt to offer a tribute to the glory of commerce as exemplified by that institution.”

THE FAÇADE WAS HAILED FOR THE LARGEST SCULPTURAL GROUPING IN THE WORLD AND THE BIGGEST DISPLAY OF TIFFANY GLASS.

Mike Wallace, the coauthor of Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, described the terminal’s construction as emblematic of the city’s “intense quest for connectivity in the two decades between the consolidation of Greater New York and the First World War. The new Grand Central was imbued with the culture of connectivity. Not only did its expansion and electrification aim to boost the volume and velocity of passenger traffic, but it was a circulatory marvel.”

When Grand Central was finally finished, the only thing lacking was adjectives. The Times produced a special section of the newspaper and hailed the terminal as “a monument, a civic center, or, if one will, a city. Without exception, it is not only the greatest station in the United States, but the greatest station, of any type, in the world.”

THE PARK AVENUE VIADUCT, WHICH GIRDLED THE TERMINAL, WAS COMPLETED TWO DECADES AFTER IT WAS ORIGINALLY PROPOSED.

A full century later, the journalist and novelist Tom Wolfe would write: “Every big city had a railroad station with grand—to the point of glorious—classical architecture—dazzled and intimidated, the great architects of Greece and Rome would have averted their eyes—featuring every sort of dome, soaring ceiling, king-sized column, royal cornice, lordly echo—thanks to the immense volume of the spaces—and the miles of marble, marble, marble—but the grandest, most glorious of all, by far, was Grand Central Station.”