LOOKING NORTH OVER THE OLD SMOKY YARDS,” William Wilgus recalled years later, “I idly sketched one day in 1902 an annex of office buildings.” What he envisioned would become Terminal City, or the Grand Central Zone. Whatever the name, it was destined to be transformed within a decade into some of the most valuable real estate in the world and an unlikely showcase for the flourishing City Beautiful Movement that had captured the public’s imagination through the model “White City” a decade earlier at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Among the movement’s protagonists was the architect Daniel Burnham, who had designed the beloved Flatiron Building off Madison Square in Manhattan and was invited to submit plans in the competition to design Grand Central Terminal. Burnham’s encompassing credo was “make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will not themselves be realized.” (Whatever their size in this case, no record of Burnham’s plan survives.) Wilgus got the message. His captivating vision was consistent with the goals of a New York City Improvement Commission, which sought in 1904 and again in 1907 to devise a coherent and homogenous urban master plan, just as the city commissioners had sought to do a century before when they imposed the street grid.

But, as Robert A.M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin, and John Massengale observed in New York 1900, the effort to establish a New York civic identity akin to that of Paris or Vienna failed because it materialized both too early and too late: “Too late, because by 1907 the great urban set pieces were in place or well under way: the public library, Grand Central and Pennsylvania stations, and the development of an ‘acropolis of learning’ on Morningside Heights. Too early, because the grand scale of the parks, parkways and boulevards would not seem urgently needed until the automobile became an everyday thing 30 years later.”

Wilgus envisioned a civic center, opera house, hotels, office buildings lining a grand boulevard—a planned, harmonious city to replace the obstructive terminal and the chasm occupied by tracks and trains that were the logical extensions of an architecturally illogical city. “The changes which are to come about within a comparatively short time will entirely alter the complexion of the city,” Mayor Seth Low said in 1903. His forecast barely scratched the surface. The Times proclaimed the new depot “more than a gateway, more than a terminal. The terminal proper, the great head house, and its accompanying buildings, are simply the heart and the cause of a group of buildings that has best been described as ‘terminal city.’ ”

WHEN NEW YORK CITY released its real estate valuations in October 1913, Grand Central was already the highest-valued property, at $17.7 million (Pennsylvania Station was second, at $16.4 million, but the disparity would widen as the real estate around the terminal became even more desirable). By 1914, the assessed valuation of properties bounded by 41st and 57th Streets and Lexington and Madison Avenues had more than doubled, from $55 million, when construction on Grand Central began, to $117 million. A decade later, it would more than double again. By 1946, a peak year for long-haul passenger train traffic, the New York Central had a stake in 21 buildings, whose assessed value was more than $121 million.

What’s so striking about Grand Central’s impact on real estate development is that Penn Station had so much less. “While Grand Central was intricately interwoven into the city around it, Penn Station stood apart,” the urban historian James Sanders has written. Penn Station spawned a hotel or two—the Pennsylvania, then the world’s largest, across Seventh Avenue, and the New Yorker on Eighth Avenue and West 34th Street. But it never generated the critical mass and concomitant magnetism that would lure corporate headquarters from downtown to Park Avenue and beyond. Grand Central made Midtown.

“A combination of factors pushed the Grand Central area ahead: for one thing, it had a head start, since there had been a train station on the site since 1871, and both the first two Grand Centrals attracted high-end hotels, etc.,” said Tony Hiss, the author of In Motion: The Experience of Travel.

For another, Wilgus’s sinking and covering of the rail yard around Grand Central and his invention of air rights for this property led to a building boom in the Roaring ’20s that far outstripped any development around Penn Station. So it was already a desirable neighborhood when it came to post-WWII office building redevelopment.

Another contributing factor may have been that, although it was home to the Long Island Rail Road, until the post–World War II consolidation and bankruptcies of New Jersey railroads, Penn Station didn’t have a monopoly on commuters coming in from the west, many of whom went to Hoboken or Jersey City and got to the city on ferries or took the Tube, while, of course, Grand Central Terminal had all the traffic coming from the north right from the start. Also Grand Central to Wall Street is a straight shot on the subway for commuters.

Fully a century later, the West Side of Manhattan is developing largely in spite of Penn Station, not because of it.

EVEN BEFORE IT WAS FINISHED, Grand Central became the impetus for an extraordinary urban renewal and repurposing of nearby property. American Express’s stables, the Steinway piano factory, and the F & M Schaeffer Brewery would give way to fashionable apartments, hotels (the Ambassador, Biltmore, Commodore, Ritz-Carlton, and Waldorf-Astoria, the new Grand Central Palace, the Roosevelt, the Barclay and Park Lane), a post office, and the Central’s own offices—all lures for the multicolored cabs that, Thomas Wolfe wrote, now descended on Grand Central “like beetles in flight.”

With Grand Central acting as an anchor, Park Avenue was elevated into New York’s most prestigious address. “The story of Park Avenue is the old story of Cinderella,” Arthur Bartlet Maurice, an author and editor wrote, “yesterday a kitchen drudge of a street, today a resplendent Princess; and the Fairy Godmother who waved the wand and wrought the change was electrification.”

By 1917, the Biltmore Hotel and the Yale Club graced Vanderbilt Avenue. Sloan & Robertson’s Eastern Offices Building, better known as the Graybar Building (for Elisha Gray and Enos Barton, Western Electric’s founders), opened on Lexington Avenue (the Graybar may be the only building decorated with rats; they’re climbing up the cables that secure the canopy and resemble the ropes used to moor ships).

Within another decade, the Commodore Hotel, the 54-story Lincoln Building, the 56-story Chanin Building, and the 77-story Chrysler Building, which reigned for less than a year as the world’s tallest, until it was eclipsed by the Empire State Building (it is still the world’s tallest steel-supported brick building), rose on East 42nd Street. Buildings and Building Management magazine reported in 1920 that 100 millionaires lived at 270 Park Avenue. And just as Park Avenue would be glamorized within two decades all the way to 96th Street, East 42nd Street would be revitalized block by block by a progression of the Bowery Savings Bank, the Daily News Building, Tudor City, and eventually the United Nations headquarters, which, appropriately enough, replaced a row of slaughterhouses. Each building was home to more stories than merely the number of floors suggested.

THE BILTMORE, designed by Warren & Wetmore, opened on New Year’s Day 1913 and was operated by Gustav Bauman of the fashionable Holland House on Fifth Avenue until he fell from a hotel window the following year. Its two towers flanked an Italian garden in the summer and an ice-skating rink in the winter. Graced by a grand ballroom that doubled as a roof garden, the Biltmore was where Henry Ford attempted to broker peace before World War I and where Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald honeymooned (and were evicted for disturbing the peace). The hotel later housed the Grand Central Art Galleries, originally located in the terminal. The Biltmore was, perhaps, most famous for its lobby meeting place “under the clock,” where, among countless others, the reclusive J.D. Salinger would meet William Shawn, editor of the New Yorker.

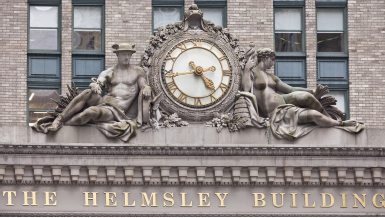

THE FAÇADE: CENTRAL WAS DEFTLY EDITED TO GENERAL ON 230 PARK AVENUE, THEN OBLITERATED ALTOGETHER. HELMSLEY-SPEAR SOLD IT IN 1988 BUT INSISTED ITS NAME REMAIN.

The 34-story New York Central Building (later the Helmsley Building), also designed by Warren & Wetmore, straddled Park Avenue just across 45th Street from the terminal. “The design and ornamentation celebrate the prowess of the New York Central Railroad, which had its headquarters on the premises,” Andrew Dolkart and Matthew A. Postal wrote in their Guide to New York City Landmarks. “A sense of imperial grandeur is created by marble walls and bronze detail, which includes extensive use of the railroad’s initials. The Chinese red elevator doors open into cabs with red walls, wood moldings, gilt domes, and painted cloudscapes.” But even before the headquarters was finished in 1929, the New Yorker complained that “sunset comes to Park Avenue about two o’clock these days.”

WHITNEY WARREN’S PALATIAL HEADQUARTERS FOR THE NEW YORK CENTRAL AT 230 PARK AVENUE WOULD BECOME THE KEYSTONE OF TERMINAL CITY.

Still, the building and its ornate cupola became beloved. They endure as the sole remnant of the Court of Honor proposed by Charles Reed in 1903. (The steel frame was completed in 1928, just hours after Chauncey Depew, the legendary chairman of the New York Central, died. Depew is remembered most as the name of what is now a private street on the terminal’s eastern flank and as an engaging after-dinner speaker. “I get my exercise acting as a pallbearer to my friends who exercise,” he often said. Depew defined a pessimist as a man who thinks all women are bad. An optimist, he said, “is one who hopes they are.”)

While Reed’s concept for a vast civic plaza was never realized (he died in 1911) and no single architect would integrate all the buildings that flanked Park Avenue, “they nonetheless created a precinct of high-rise buildings in the city where a common aesthetic prevailed,” the architect Deborah Nevins has written. The New York Central Building “and its broad arms and tower closed the vista from upper Park Avenue and created a monumental boundary to this unique architectural environment,” she wrote. “The life of this enclave was brief, for it was soon to be replaced by the glass skyscrapers of the 1950s.”

By 1926, 15,000 residents and 25,000 workers could reach their homes or offices through Grand Central without ever going outside. The zone was likened to “a gigantic rabbit warren,” which not only connected them to the terminal, but accessed the Interborough Rapid Transit Lexington Avenue line and, after 1918, a shuttle to Times Square (along the subway’s original route uptown).

GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL was always about more than transportation. It was, as Whitney Warren imagined it would be, an exotic bazaar. Even during the Depression, Fortune magazine enthused, “More badly busy, more madly various than Coney Island are the station’s 61 concessions. Kiddy Cars are sold at August Stumpf’s, diamond rings at Samuel Kamerow’s, shoe shines in the Union News Co. stands, orchids at J.S. Nicholas’s, oysters at Mendel’s Bar, shaves at J.P. Carey’s, theater tickets, groceries, dress suits, sodas, electric light bulbs, books, lunches, radiograms, cigars, stamps. And from it all rolls into Central’s pockets about $2 million-a-year.”

AN ELEVATOR INDICATOR IN THE ORNATE LOBBY OF 230 PARK. THE BUILDING PLAYED A ROLE IN ATLAS SHRUGGED AND THE GODFATHER.

As early as 1937, the Columbia Broadcasting System announced that the terminal would become home to experimental television studios directly above the main waiting room. CBS installed broadcasting equipment there two years later and the Chrysler Building across the street was fitted for a transmitter. Broadcasting was curtailed during World War II, but right after the war the technology and the talent coalesced. The network would broadcast from there until 1964 (despite the fuzzy images sometimes produced on television sets at home because of vibrations from the trains below). Among the programs that originated from one of four studios were The CBS Evening News with Douglas Edwards, Edward R. Murrow’s See It Now, The Goldbergs, and What’s My Line? In 1958, what was described as the first major videotape facility in the world opened there.

The 60 Minutes creator Don Hewitt remembered his first visit to the CBS studio: “They had cameras and lights and makeup artists and stage managers and microphones just like in the movies, and I was hooked. I had been passing through Grand Central every day on my way to work and never knew that upstairs, over the trains and the waiting room and the information booth, was an attic stuffed with the most fabulous toys anyone ever had to play with.” Hewitt continued, “I was mesmerized. As a child of the movies, I was torn between wanting to be Julian Marsh, the Broadway producer in ‘42nd Street,’ who was up to his ass in showgirls, and Hildy Johnson, the hell-bent-for-leather reporter in ‘The Front Page,’ who was up to his ass in news stories. Oh my God, I thought, in television I could be both of them.” The former studio is now a tennis court.

FROM 1922 TO 1958, the sixth floor of the terminal was home to Grand Central Art Galleries, which was founded by John Singer Sargent, Walter Leighton Clark, Edmund Greacen, and other artists, originally as a nonprofit cooperative. An estimated 5,000 people attended the opening in 1923, which featured paintings by Sargent, Wayman Adams, and Cecilia Beaux and sculpture by Robert Aitken and Daniel Chester French. The 15,000-square-foot gallery billed itself as “the largest sales gallery of art in the world.”

The following year, the galleries opened an art school on the seventh floor. The galleries remained at Grand Central until 1958; their former display space is now the railroads’ operations center. The terminal would also become home to a newsreel theater and restaurants. Its allure would spill onto 42nd Street, where two dozen skyscrapers connected to the terminal through underground passageways would sprout, and to Park Avenue, which would become synonymous with opulent living. It drew people like iron filings to a magnet, by 1947 handling more than 65 million passengers, or the equivalent of 40 percent of the nation’s total population. And, after it experienced ups and downs like the railroads had themselves, the terminal’s influence would reverberate into the next century too.

THE HOTEL, APARTMENT AND OFFICE TOWERS of Terminal City themselves typically would not reverberate, however, thanks to innovative insulation. H.G. Balcom, a structural engineer, was credited with conceptualizing supporting columns disconnected from the vibrating track floor and the viaduct for the 20-story Park-Lexington Building (his portfolio would later include the Empire State Building, Rockefeller Center, and the Waldorf-Astoria).

THE CENTRAL’S STYLIZED LOGO WAS SUCCEEDED BY AN UPSIDE-DOWN ANCHOR AND, FOR THE CENTENNIAL, THE FAMOUS CLOCK.

Many of the buildings on Park and Vanderbilt are separated from the sidewalk by a visible two-inch slot containing a vibration barrier. Moreover, the steel girders that support the tracks and the roof of Park Avenue are separated from the structural stilts, which support the buildings and were packed in layers of lead, asbestos, sheet iron, and other baffling at their base, deeper in bedrock. (When one apartment building on Park Avenue rattled nonetheless, the vibration was blamed on two protruding bolts that had lodged against a girder that supported the tracks and the street above.)

The seam between the sidewalk and the buildings mitigated the rumbling of trains in the bowels of Manhattan but didn’t stop it entirely. Frederick Jack noticed the vibration in Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again, and the assurances of the doorman of his building on Park Avenue were not entirely satisfactory. You might say Jack was rattled. “He would have liked it better if the building had been anchored upon solid rock,” Wolfe wrote. “So now, as he felt the slight tremor in the walls once more, he paused, frowned and waited till it stopped. Then he smiled. ‘Great trains pass under me,’ he thought. ‘Morning, bright morning, and still they come—all the boys who have dreamed dreams in the little towns. They come forever to the city. Yes, even now they pass below me, wild with joy, mad with hope, drunk with their thoughts of victory. For what? For what? Glory, huge profits, and a girl! All of them come looking for the same magic wand. Power. Power. Power.’ ”

IF ANY ONE MAN DESERVED THE CREDIT for Grand Central’s success as a transportation hub and as the catalyst for creating Midtown, it was William Wilgus. He would never get it, though. In 1907, the 6:15 p.m. express from Grand Central to White Plains flew off the tracks as it rounded a curve at 205th Street in the Woodlawn section of the Bronx. Twenty commuters were killed instantly and another 150 were injured. Scapegoats were demanded. Wilgus was an obvious target. Officially, the railroad blamed a faulty rail, but Central officials—and Wilgus—became convinced that the real flaw was “nosing,” a tendency toward horizontal alignment of the locomotives, which the railroad and General Electric had been aware of and were trying to correct. Wilgus’s meticulously documented conclusion about the cause would be devastating to the Central if it became public. He was advised by the railroad’s chief counsel to destroy his evidence, which he did. But he later re-created his conclusions and included them in papers he would donate to the New York Public Library. His report would remain undisturbed there until after his death.

On July 11, 1907, after learning that the railroad was redesigning the locomotives without consulting him, Wilgus resigned. Replying to the departing chief engineer, who by then was making a very respectable $40,000 a year, W.C. Brown, the railroad’s senior vice president, wrote, “The great work undertaken and practically completed by you, of changing the power within the so-called electric zone and the reconstruction of the Grand Central Station, was the most stupendous work of engineering I have ever known; and it has gone forward practically without a halt, certainly without a failure in any essential feature.”

Wilgus, who was succeeded by George Kittredge, Edwin B. Katte, and George A. Harwood, would spend the rest of his life seeking the credit he deserved. In 1909, he received a measure of vindication when the Central’s directors, while embracing Whitney Warren’s resplendent concourse, restored two features that Wilgus and Reed & Stem had originally proposed: the elevated roadway that routed Park Avenue around the terminal, and the structural foundation for a revenue-producing tower that might someday be built over the building.

Four years later, though, as best as can be determined, Wilgus was never mentioned publicly when Grand Central was formally dedicated. Nor would his bold plan to bore 60 miles of rail freight tunnels to link Manhattan with Staten Island and New Jersey ever be realized. He would become deputy director general of transportation for the American Expeditionary Forces under General Pershing and was credited with the strategy that won the Battle of Saint-Mihiel in September 1918, which broke the German defensive line and facilitated the Americans’ Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Whitney Warren, too, merits a World War I footnote. Warren was chosen to rebuild the Louvain Library in Belgium, insisting that it bear the inscription “Furore Teutonico Diruta: Dono Americano Restituto” (destroyed by German fury; restored by American generosity). Warren, who became an admirer of Mussolini, lived long enough to see the library destroyed again, by the Nazis.

“GRAND CENTRAL ACHIEVED A GREATER IMPACT on the urban fabric of New York than any other building project in the first half of the 19th century, until construction began on Rockefeller Center,” Kurt Schlichting wrote. Less than a decade after the terminal opened, Railway Age concluded, “It is doubtful if even the most optimistic participants in the work in question ever looked forward to seeing just how great an effect the electrification and terminal improvement were going to have on the development of New York City.” William Wilgus had, and he was right.