Some vagrants—when they were still quaintly called hoboes or tramps—had lived for years in subterranean dungeons beneath the Waldorf and other Park Avenue properties, in dank, rumbling, labyrinthine tunnels devoid of light except for the occasional naked incandescent bulb, but free from the interference, regulation, or danger associated with meddlesome public shelters.

They cooked their food on hissing steam pipes stripped of their asbestos covers and they emerged from sordid and sooty sanctuaries during the day only to panhandle for bare essentials. (A fire that began in the subterranean tunnels under Grand Central shut the terminal down in 1985, but police said squatters living in a boxcar were not to blame.) Jennifer Toth, who gave them faces in her book The Mole People, recalled a man named Seville who was panhandling in Grand Central when a commuter gave him a bag containing a loaf of bread and a pound of baloney. He thanked the man, then shouted: “Pardon me, sir, would you happen to have some Grey Poupon?”

By 1988, as Grand Central celebrated its 75th birthday, city officials estimated that as many as 500 homeless people were living in the terminal on any given night and that 50 or so had been encamped there for a year or more. “It’s a metaphor for New York in 1988 in a shrine of such beauty to have such misery,” said Robert M. Hayes, a lawyer who successfully sued the state in a right-to-shelter case and founded the Coalition for the Homeless.

HOW GRAND CENTRAL DEALT with the challenge also provided an object lesson for the rest of America. Drop-in shelters were created to steer homeless people to permanent homes. Sometimes, officers were forced to eject aggressive panhandlers, a solution that proved temporary and invited fire from advocates for the homeless (as did the removal of benches from the waiting room). The Metropolitan Transportation Authority hired the Bowery Residents Committee to provide outreach services, and transit officials also worked in concert with the Grand Central Partnership, an amalgam of property owners in a 50-square-block area around the terminal.

After Mobil Oil abandoned its East 42nd Street headquarters for suburban Virginia, those property owners convened an innovative self-taxing business improvement district in 1988 to spruce up the neighborhood and provide amenities that the city government could no longer afford. (Its 120 full-time employees, including 33 public-safety officers and 56 sanitation workers, and a nearly $13 million budget make it among the nation’s largest such districts. The annual surcharge on 204 properties was initially 10 cents per square foot, or what amounted to an extra 1 to 2 percent in real estate taxes; it ranged from more than $250,000 for the Metropolitan Life Building to $154 for a nearby delicatessen.)

“The truth is,” the architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote then, “that the Grand Central neighborhood does not work as it is now—it is too dirty, too pressured, too troubled by a large homeless population and too lacking in amenity for everyone else.” The partnership, he said approvingly, “is based on the idea that the terminal is not just a building, but the symbolic anchor of a neighborhood.” Through Daniel A. Biederman, its president (whom the partnership borrowed from the wildly successful Bryant Park Restoration behind the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue), and Peter L. Malkin, a lawyer and real estate investor whose office faced Grand Central (and whose father-in-law, Lawrence Wein, was once an owner of the Empire State Building), the business improvement district spawned similar public-private partnerships across the country. A subsidiary of the partnership transformed a nearby former parochial school into a center where hundreds of homeless people who congregated around Grand Central could be fed and could shower, receive counseling, and even stay overnight. “Enlightened self-interest and then some,” said Robert Hayes, the advocate for the homeless (although the partnership was later criticized when some outreach workers aggressively rousted vagrants in and near Grand Central).

In New York City alone, 67 such business improvement districts invest $100 million collectively in public amenities. In addition to installing uniform signage and removing litter, the Grand Central Partnership raised more than $1.5 million to floodlight the terminal’s south and west façades. Since 1991, the terminal has been bathed in 136,000 watts of floodlight from buildings across the street. The blue and magenta tints were designed by Sylvan R. Shemitz, a lighting engineer whose goal, he said, was to make New York “a lively, friendly and joyful place.”

IN ITS FIRST CENTURY, Grand Central has played a prodigious role in the annals of urban planning, beginning with William Wilgus’s ingenious monetization of air rights (the ability to transfer those rights between adjacent properties was also introduced in New York in 1916 in the nation’s first zoning ordinance). The skyrocketing value of those rights nearly doomed Grand Central until the U.S. Supreme Court delivered another victory to the terminal by upholding its landmark status and a municipality’s right to confer it. But Grand Central’s influence on planning, as profound as it was, went well beyond establishing air rights and historic preservation as fundamentals of real estate law and development.

Recounting the cycles of building, obsolescence, and denser rebuilding that characterized Manhattan’s inexorable march uptown, James Marston Fitch, a Columbia architecture professor, and Diana S. Waite, a researcher for the state’s parks department, concluded, “Only three projects in Manhattan’s history have been able to slow down, much less to stop or reverse, this remorseless process of expansion and decay”: Central Park, Rockefeller Center, and Grand Central Terminal. Pointedly, they did not include Pennsylvania Station, which, for all its glory, spawned a few nearby hotels but never became a catalyst for further development (only now are the Hudson Yards west of the station fulfilling their potential).

Those three megaprojects shared a number of epochal characteristics, not the least of which was they each defied the inviolable street grid that city commissioners had presciently mapped in 1811 from Houston Street all the way uptown to 155th Street. “They are significant,” Fitch and Waite wrote, “for having served to polarize the forces of growth, thus acting to stabilize the whole center of the island rather like the electro-gyroscopes employed on large ocean liners. They have not been passive containers of urban activity; instead they have acted as generators of new urban energies, infusing the urban tissues around them with nourishment and strength. This capacity is a mysterious one in urban affairs, not much analyzed and never adequately explained.”

Attempting to do just that, the authors concluded that Wilgus’s perspicacity converted the terminal complex “from an inert obstacle to urban development into a dynamic reciprocating engine for urban activity.” The railroad air rights that Wilgus pioneered have produced a private and public development bonanza. In Manhattan alone, profits were plucked from thin air by Riverside South, where 10,000 apartments were built over the old New York Central West Side yards; the Hudson Yards project over the tracks west of Penn Station; and the Atlantic Terminal development, including the Barclays Center arena.

GRAND CENTRAL FUNCTIONED as a metaphysical gateway in other respects. For decades, only two jobs held out much promise for black men. They could either apply for work with the post office or hope to be hired as Pullman porters. At one point, when its ranks swelled to 20,000, the Pullman Company was the largest single employer of black men in the United States. Their chief patron was A. Philip Randolph, who arrived in Harlem in 1911, would become the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, would be denounced as the most dangerous black man in America, and would lead the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Because porters traveled routinely between the North and South, they were instrumental in awakening southern blacks to the Great Migration. And they were pioneers in the battles for equal rights.

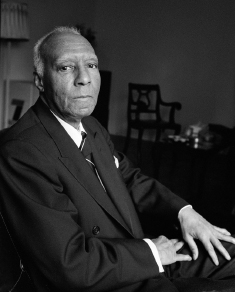

A. PHILIP RANDOLPH, “THE MOST DANGEROUS BLACK MAN IN AMERICA.”

“If Martin Luther King was the father of the civil rights movement,” wrote Larry Tye, author of Rising from the Rails, “then A. Philip Randolph was the grandfather of the civil rights movement.” The porters were always civil but had few rights. Their pay was poor, and they depended heavily on tips. (“Tipping is objected to by austere and frugal American moralists upon the ground that it undermines the manhood and self-respect of the tippee,” the Times opined. “But this proposition loses all its force when the tippee is of African descent.”) Regardless of their given names, they were condescendingly referred to by most passengers as “George,” the first name of the Pullman Company’s founder and inventor. (Pullman’s second president was Robert Todd Lincoln, Abe’s son; the company would continue producing railroad cars and prototypes until 1987, when it was absorbed by Bombardier.) In 1914, presumably as a joke, a group of white men, many of them named George, formed a Society for the Prevention of Calling Sleeping Car Porters George. Whatever its motives, the Pullman Company responded by placing a sign in each car with the given name of the porter on duty. As it turned out, only 362 of 12,000 porters surveyed were named George.

The sleeping car porters union was organized in New York in large part by Ashley L. Totten, a Virgin Island–born porter for the New York Central, after periodic rebuffs by Pullman and its lopsided company union, the Pullman Plan of Employee Representation (which left porters with a basic work month of 400 hours or 11,000 miles and a $7.50 wage hike to $67.50 a month). In June 1925, Totten approached the 36-year-old Randolph, then editor of The Messenger, a black political and literary magazine, on 135th Street in Harlem and invited him to address the Pullman Porters Athletic Association.

Totten later recalled that he was looking for someone “who had the ability and the courage, the stamina and the guts, the manhood and determination of purpose to lead the porters on.” Meeting secretly in Harlem on August 25, 1925, Totten and several hundred other porters from the New York Central and neighboring railroads voted to organize. They invited Randolph, an avowed Socialist and an outsider immune to company pressure, to be their president. Randolph, whose brother was a former porter, eventually agreed. “As history had shown, no Pullman porter could survive the attempt,” Jervis Anderson wrote in his biography of Randolph. “Randolph’s pre-eminent credential was that he could not be picked off by the Pullman Company.” The porters were in a fighting mood by then, and their motto, “Fight or Be Slaves,” bore no hint of Stepin Fetchit servility. Totten was fired by Pullman and became the brotherhood’s secretary-treasurer. Benefiting from New Deal labor legislation, the porters finally signed their first collective bargaining agreement with the Pullman Company in 1935 and won a charter from the American Federation of Labor that same year—the first black union to do so.

The union’s agenda wasn’t limited to wages, though, or only to its members. In 1941, Randolph threatened a march of 100,000 blacks on Washington unless the government banned discrimination by defense contractors. On June 25, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt did so and created the Fair Employment Practices Committee.

PERHAPS THE TERMINAL’S MOST ENDURING EXPORT is about time. Until 1883, virtually every town in the country set local time by the sun. Typically, noon would be regularly signaled so people could synchronize their clocks and watches. (A ball drop down a flagpole was considered most reliable, ringing a gong less so, given the slower speed of sound. In New York the daily ball drop downtown alerted mariners and delivered a telegraphic notification to the city’s more than 2,000 jewelry stores so they could adjust their time pieces.) Whatever the method, the divergent definitions wreaked havoc on timetables as the railroads spread geographically and gained speed. Suddenly, every minute and second counted. But efforts to standardize time were uneven at best and disconnects were common. In On Time, Carlene E. Stephens recounted the epochal experience of Richard Cobden, the British calico baron, who was traveling by train from Boston to Providence in 1835:

First, his train was delayed. Eventually it set off, but the passengers had to get out and walk at a stretch where the track was unfinished. Finally, the car caught fire—twice—and the travelers not only suffered more delay but received a dousing in the frenzy to put out the flames. By the time Cobden arrived at his destination, the hour was so late that all the inns in town were full. He bedded down on chairs in a public hall. Noting the elaborate instructions in the railroad regulations for what to do when delays occurred, we may conclude that such experiences were common.

Kind of puts your daily commute in perspective.

BY THE 1850S, Henry David Thoreau was proclaiming that trains on the Fitchburg Railroad in Massachusetts, which passed Walden Pond, were so precise “and their whistles can be heard so far, that farmers set their clocks by them.” But each railroad imposed its own standard, usually depending on where it was headquartered. Professor J.K. Rees of Columbia estimated that by 1883, the number of local standards, once as many as 100, had been halved to a still considerable and confusing 53. Meanwhile, the trackage that crisscrossed the country had expanded exponentially, from a mere 73 miles in 1830 to 9,000 by midcentury and more than 30,000 just one decade later. Cities served by multiple lines were especially vulnerable to chronological chaos. Buffalo’s station, for example, displayed three clocks: New York time for the New York Central, Columbus time for the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, and Buffalo local time.

A passenger traveling from Portland, Maine, to Buffalo could arrive in Buffalo at 12:15 according to his own watch set by Portland time. He might be met by a friend at the station whose watch indicated 11:40 Buffalo time. The Central clock said noon. The Lake Shore clock said it was only 11:25. At Pennsylvania Station in Jersey City, New Jersey, one clock displayed Philadelphia time and another New York time. When it was 12:12 in New York, it was 12:24 in Boston, 12:07 in Philadelphia, and 11:17 in Chicago. “Had there been stretched across the Continent yesterday a line of clocks extending from the extreme eastern point of Maine to the extreme western point on the Pacific Coast,” the Times mused, “and had each clock sounded an alarm at the hour of noon, local time, there would have been a continuous ringing from the east to the west lasting three-and-a-quarter hours.”

An amateur astronomer, William Lambert, proposed to Congress as early as 1809 that with the nation growing westward, time be standardized. His proposal languished for half a century, even as England, Scotland, and Wales (which covered a much smaller band longitudinally than the United States) uniformly adopted Greenwich Mean Time in 1848. In 1853, an inaccurate watch led to a crash on the Camden & Amboy railroad in New Jersey. Three days later, a Providence & Worcester train carrying spectators to a yacht race at Newport and speeding to make a steamboat connection collided on a blind curve of a single track, killing 14 passengers. A brakeman, acting as the conductor, calculated that he had enough time to switch to a siding but was relying on a watch borrowed from a milkman that was running slow. “Our columns groan again with reports of wholesale slaughter by Railroad trains,” the Times fumed. As a result, railroads in New England adopted a single standard.

The need for a national standard was hastened by the commercial development of the telegraph and, in 1862, when Congress authorized the building of the first transcontinental railroad. A year later, a rash of collisions spurred the Reverend Charles F. Dowd, coprincipal, with his wife, of Temple Grove Ladies’ Seminary in Saratoga Springs, New York (a girls’ boarding school, which later became Skidmore College), to suggest multiple regional time zones.

He sketched out his proposal in 1869 and the following year presented it to railway superintendents in New York. He elaborated in a pamphlet proposing four zones 15 degrees longitude wide (the sun moves across 15 degrees every hour). Railroad trains “are the great educators and monitors of the people in teaching and maintaining exact time,” said William F. Allen, editor of the Traveler’s Official Railway Guide. But “there is today scarcely a railroad center of any importance in the United States at which the standards used by the roads entering it do not number from two to five. The adoption of the system proposed will reduce the present uncertainty to comparative if not absolute certainty.”

In 1882, Connecticut bowed to a Yale astronomer, Leonard Waldo, and enacted a standard time that replaced the separate times set by railroads to synchronize their schedules separately with the clocks in Boston, Hartford, New Haven, New London, and New York. A national standard was something else entirely. As Allen wrote, “How can this reform be accomplished? It is on record that a small religious body once adopted two resolutions as a declaration of its faith. The first was, Resolved, that the saints should govern the earth. Second, Resolved that we are the saints.”

A version of Dowd’s proposal was finally embraced by the General Railway Time Convention in 1883—representing most of the lines that controlled 93,000 miles of rail—to take effect nationwide a month later at noon, Sunday, November 18. For the first time, a traveler going cross-country could rely on the minute hand of his watch telling the correct time, with only the hour changing as he passed from one time zone into another. No longer would clocks be chiming continuously for three and a quarter hours. Instead, they would ring in each hour simultaneously, even if the hour would be different in each time zone.

In New York, they would strike noon approximately 3 minutes, 58 seconds, and 38 one-hundredths of a second earlier than they had the day before. All over the country, Americans greeted the change with Y2K trepidation and with not a little resentment that the railroads were once again impinging on their daily routines. A local prophet in Charleston, South Carolina, warned that toying with time would provoke divine displeasure (sure enough, a major earthquake struck there three years later). Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Detroit refused to comply, and Cincinnati delayed adoption of standard time for seven years. The mayor of Bangor, Maine, rejected the new standard, declaring that “neither railroad laws nor municipal regulations have the power to change from the immutable laws of God.”

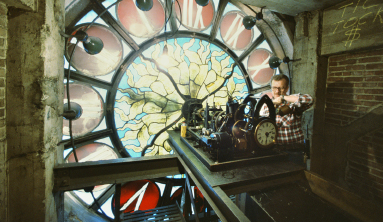

CLOCK MASTER WILLIAM STEINHAUSER MAINTAINED THE 13-FOOT-DIAMETER TIMEPIECE. THE VI PANE OPENS FOR A PARK AVENUE VIEW.

Boston’s commissioner of insolvency, Edward Jenkins, refusing to comply with the new standard, declared Horace Clapp in default on November 19, 1883, because he got to court a minute late by local time but 15 minutes early under standard time. Massachusetts Superior Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes ruled that while the standard had not been adopted by the state legislature, the popular community consensus—standard time, as imposed the day before in Boston by the city council—applied.

J.M. TOUCEY, general superintendent of the New York Central, announced that beginning November 18 all trains would run on “New Standard, 75th median time, which is four minutes slower than the present standard.” The official timekeeper at the time was the Western Union Company at 195 Broadway. There, in Room No. 48, James Hamblet, the superintendent of the Time Telegraph Company, planned to stop his regulator clock at 11 a.m. New York time, pause the requisite 3 minutes, 58 seconds, and start it again on standard time on the 75th meridian as verified with observatories in Washington, D.C., Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Allegheny, Pennsylvania.

The first noon under standard time would be signaled by the regular dropping of the 42-inch-diameter, 125-pound copper time ball from a 22-foot-high staff atop the Western Union Building, triggered by a signal from the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington that tripped a magnetic latch. Trains across the country would be stopped to adjust their timetables to standard time. A crowd gathered in front of the Western Union Building to celebrate the “Day of Two Noons” and to watch the time ball drop twice—first on local time and four minutes later on the new eastern standard time. Despite the public apprehension about changing times, the New York Tribune dryly concluded, “There was no convulsion of nature, and no signs have been discovered of political or social revolution.”

Even earlier, at 10 that morning in New York, a horological revolution took place. Grand Central became the first railroad station in the nation to adopt standard time. Seeking to minimize the disruption, the New York Central figured earlier was better. To accommodate the Central, Hamblet stopped the pendulum of his regulator clock at 9 a.m. instead of 11.

Following the American example, countries around the globe adopted time zones too. “No crisis forced the railroads to alter the way they kept time, no federal legislation mandated the change, no public demand had precipitated it,” the historian Carlene Stephens wrote. “The railroads voluntarily rearranged the entire country’s public timekeeping, albeit under the threat of government interference if they did nothing. The country, for the most part, went along without too much reluctance.”

Industrialization and urbanization were taking their toll on spontaneity, even as travel became speedier and leisure time increased. Americans were becoming “increasingly attentive to and accountable for living and working in synchronized ways,” Stephens wrote, although it would take until 1918 for Congress to formally establish standard time and daylight savings time.

Today, Grand Central’s master clock is located on the Lower Level near Track 117. It looks like an oversize blue refrigerator and is synchronized every second by a signal from the atomic clock at the Naval Observatory in Bethesda, Maryland, where time is measured by the vibrations of a cesium atom. The master clock controls every official timepiece in the terminal, from the four-faced golden ball clock atop the information booth in the Main Concourse to the clock on the 42nd Street façade. Still, one clock in the terminal, in the Graybar Passage looking west toward the Main Concourse, sometimes sends mixed messages. The hands are always correct, but the sign beneath it is wrong for nearly half the year. The Central was so proud of its role in inaugurating time zones that the builders of Grand Central carved “Eastern Standard Time” into the marble under the clock in 1913, five years before Congress imposed daylight savings time.

Western Union’s shift to standard time in New York was overseen by William Allen, the Railway Guide editor, whose name, the Times declared, “will be forever connected with the successful accomplishment of one of the most useful reforms possible to the heretofore often bewildered traveler.” How long Allen was remembered is arguable. The Reverend Charles Dowd faded from public memory even faster, though. Dowd died underneath the wheels of a Delaware & Hudson locomotive at a grade crossing in Saratoga, New York, in 1904. History does not record whether the train was on time.