THE TEMPLE OF DENDUR was built in Egypt 19 centuries before Grand Central Terminal. It celebrated a river, not a railroad. And it stood 6,000 miles from the middle of Manhattan. But the Temple and Grand Central had one very important person in common, a woman whose prestige led to their salvation. Momentum for what might very well have been the end of Grand Central came to a screeching halt with a surprise telephone call in 1975 to the Municipal Art Society. “There’s a woman on the phone,” Laurie Beckelman, a dubious 22-year-old assistant, told her boss, Kent Barwick, “who claims to be Jackie Onassis.”

Onassis was no newcomer to historic preservation. Her love affair with the Temple of Dendur started while her first husband was president and she was restoring the White House. The Egyptian government offered up a smorgasbord of monuments to the United States in gratitude for gifts from the Kennedy administration to save the temple and other antiquities from flooding caused by construction of the Aswan Dam. Onassis immediately chose the temple. Years later, she moved into a Fifth Avenue apartment that provided a stunning vista of the salvaged temple, which was installed in a glass jewel box at the Metropolitan Museum of Art across the street. By special arrangement, the museum would illuminate the temple at night so she could show it off to guests.

Onassis’s call to the Municipal Art Society was prompted by an article in the Times. A few days before, on January 21, 1975, State Supreme Court Justice Irving H. Saypol had voided the designation of Grand Central Terminal as a city landmark. The decision went well beyond the realm of aesthetic criticism, although Saypol gratuitously belittled the terminal as leaving “no reaction here other than of a long neglected faded beauty.” Without ruling on the constitutionality of the decade-old landmarks law, he decided in favor of the Penn Central Railroad, owners of the terminal. By not allowing the railroad to place a revenue-producing 59-story skyscraper above the terminal, Saypol said that the city was causing “economic hardship” so severe that it amounts to “a taking of property”—the property, in this case, being the very air rights that William Wilgus had conceived of seven decades earlier. Deep inside the Times story on Saypol’s decision was a paragraph that caught Onassis’s eye: “It was learned last night that the Municipal Art Society would announce within the next week the formation of a citywide committee to work for the preservation of the terminal and to support the city in its expected appeal.”

IN A WAY, you could blame the whole landmarking mess on William Wilgus. Arguably, his very conception of Grand Central Terminal provided the deep roots for its potential destruction. As the Central’s chief engineer, in 1903 he, in effect, created the intangible legal principle of air rights, which the successor railroad—bankrupt and hemorrhaging—wanted to transform into an office building that would generate hefty rental revenue. Unwittingly, another Wilgus innovation also laid the groundwork for the terminal’s threatened demolition. He originally envisioned a revenue-producing tower atop the depot. While it was never built, the structural support for a future skyscraper was installed as the six-story bases off the four corners of the main concourse. The tower proposal largely lay dormant for 50 years.

BY THE END OF THAT HALF-CENTURY, long-distance passenger traffic was plummeting while deficits from passenger service were ballooning. The Suburban Concourse, now known as the Lower Level, was closed altogether by midcentury. By 1954, the Central was sending only 18 long-distance trains weekdays from Grand Central to upstate and the West, compared with 32 in 1947. The Central’s president, Alfred E. Perlman (he later joined Howard Newman at the Western Pacific Railroad, but there is no evidence that he inspired the Mad magazine character), threatened to shutter Grand Central altogether and leave passengers to fend for themselves on public transportation from the Bronx or Westchester. Even from as far north as Croton-Harmon, Perlman said, “they can get into New York the way they do when they fly into Idlewild Airport.” (He also suggested integrating the city’s subway system and the Central’s Park Avenue tracks, which, he said, would be far less costly than building a proposed Second Avenue subway.)

In 1954, the Central announced that it was mulling construction of the world’s tallest building on the site of its terminal, which railroad officials claimed was running a $24 million annual deficit. The Central’s spectacular Hyberboloid, an ambitious 108-story, nearly 5-million-square-foot tower, designed for William Zeckendorf by I.M. Pei, would be topped by an observation tower that would boost its height to 1,600 feet, well beyond the 1,250-foot Empire State Building. The proposal, and a subsequent alternative (ironically by a successor firm to the terminal’s original architects), generated an outcry. Architectural Forum published a letter signed by 220 architects pleading that the terminal’s Main Concourse be spared. They called the concourse “probably the finest big room in New York” and continued their paean:

It belongs in fact to the nation. People admire it as travel carries them through from all parts of the world. It is… one of those very few building achievements that… has come to stand for our country. This great room is noble in its proportions, alive in the way the various levels and passages work in and out of it, sturdy and reassuring in its construction, splendid in its materials—but that is just the beginning. Its appeal recognizes no top limit of sophistication, no bottom limit. The most exacting architectural critic agrees in essentials with the newsboy at the door.

The Times added tentatively that “before the plans reach rigid crystallization, there is a chance that public opinion can persuade the heads of these railroads to consider some scheme whereby, without arresting the desirable progress implicit in their project, this great piece of civic architecture could be spared.” Four years later, Pei’s proposal had morphed into Grand Central City, an octagonal skyscraper that would become known as the Pan Am and later as the Met Life Building, a massive 2.4-million-square-foot hulk—surpassed in bulk at the time only by the Pentagon and the Chicago Merchandise Mart. The tower was sandwiched between Grand Central and its corporate headquarters but spared the terminal itself. The humongous building’s 45,000-ton steel frame was supported by 200 existing columns and another 95 sunk into bedrock, 55 feet below the surface. Some concessions to Grand Central were proffered. The bulk was cut from 3 million square feet. The axis was rotated to east-west, to give the New York Central Building a little more breathing room. Still, the Times’ architecture critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, wrote:

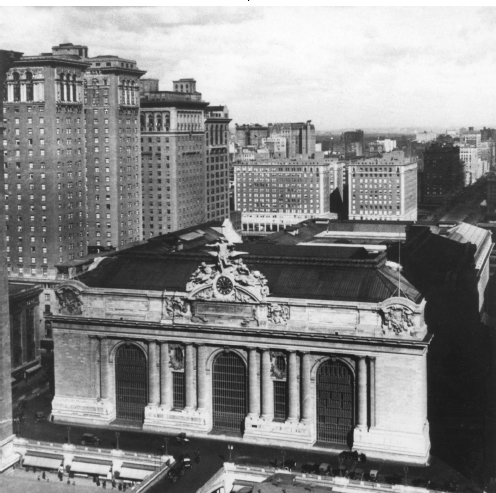

GRAND CENTRAL LOOKING NORTH, WHEN MOSTLY HOTELS AND POSH APARTMENT BUILDINGS STRADDLED PARK AVENUE.

Many planners agree that this addition to an overbuilt New York is one more rapid step toward the certain strangulation of the city, and its eventual reduction to total paralysis. However, as long as private enterprise controls city land, use and economics and legislation offer no incentives to improved urban design, such buildings are inevitable, and neither developer nor designer is to blame. The blockbuster building is here to stay, a singular symptom of one of the most disturbing characteristics of our age: A loss of human scale that seems irrevocably tied to a loss of human values.

Developed by Erwin S. Wolfson and designed by Emory Roth & Sons with Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi, the tower replaced the six-story Grand Central Terminal Office Building just north of the terminal. Grand Central City was hailed by Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller as emblematic of the genius and creativity of the free enterprise system. Harper’s magazine begged to differ. “When Commodore Vanderbilt, surely a champion of free enterprise, organized the Grand Central area, enterprise was free enough to create order in the grand manner of Versailles, on the grand scale of the railway age. What is happening now is hardly more than what happened in Rome in the Dark Ages—men tear down great works to put up the best they can.”

The critic V.S. Pritchett was even less forgiving. Noting that the Pan Am Building was financed by his fellow Brits, he observed (in an uncredited bow to William Wilgus), “No other city I can think of has anything like the undulating miles that fly down Park Avenue from 96th Street to Grand Central blocked now though it is by the brutal mass of the Pan Am Building—a British affront to the city spoken of as a revenge for Suez.”

The Central hoped that an anticipated $1 million in rentals would help stanch its bleeding. Instead, the new building touched off a simmering dispute with the New Haven Railroad over who owned the terminal and adjacent property. It also whetted the deficit-ridden Central’s appetite to develop even more real estate. In 1961, the railroad’s request to install a three-level bowling alley over the main waiting room, which would have lowered its ceiling from 60 feet to 15, was rejected by the city’s Board of Standards and Appeals (because it was located in a restricted retail area, a bowling alley would violate zoning regulations). But prominent architects and civic groups warned that the victory was just a skirmish before an inevitable epic battle over the terminal’s future.

THAT SAME YEAR, across town, the Pennsylvania Railroad had optioned the air rights over Penn Station, fulfilling a dream of Alexander Cassatt, the line’s president when Penn Station was being built (he was dissuaded by his architect from placing a hotel atop the station because the railroad owed the city a “thoroughly and distinctly monumental gateway”). The Beaux Arts–style station, flanked by 84 Roman columns, had faded even less elegantly than Grand Central, its junior by three years, since demolition was announced in 1961. It was seedy. And grimy. The roof was leaking. Maintenance costs were draining its corporate parent.

Despite protests from preservationists, demolition began on October 28, 1963, with the staccato sound of jackhammers tearing into the station’s granite skin and the lowering of a stone eagle. “Just another job,” said John Rezin, foreman of the wrecking crew. His assessment was echoed by Morris Lipsett, president of the demolition company: “If anybody seriously considered it art, they would have put up some money to save it.”

The detritus of a great station would be ignominiously dumped in the Secaucus Meadows as landfill for what would become the Meadowlands. “The message was terribly clear,” the Times’ Ada Louise Huxtable wrote. “Tossed into that Secaucus graveyard were about 25 centuries of classical culture and the standards of style, elegance and grandeur that it gave to the dreams and constructions of Western man.” A banal office building and the fourth incarnation of Madison Square Garden rose in its place. Indeed, if Pennsy passengers and Long Island Rail Road commuters felt claustrophobic, they were justified. The ceiling of the old station’s awesome main waiting room was 150 feet high. In the new one, it would barely reach 25 feet. Vincent Scully memorably summed up what had been lost. “One entered the city like a god,” he wrote. “One scuttles in now like a rat.”

BUT PENN STATION WOULD NOT DIE IN VAIN. In a city that never valued its history as much as Boston or Philadelphia did (“History is for losers,” Ken Jackson, the Columbia history professor, japes), where relatively sparse prime space is periodically recycled to produce bulkier and taller buildings, razing Penn Station fueled an unexpected backlash. “I really believe Grand Central Terminal was saved because of what happened at Penn Station,” said Peter Samton, an architect and civic leader who lobbied to save them both. Earlier in 1961, even before the wrecking crew went to work and with development threatening other historic landmarks, such as Carnegie Hall and the Alexander Hamilton Grange, Mayor Robert F. Wagner appointed a committee to research the applicability of the Bard Act, first suggested in 1913, the year Grand Central Terminal opened, and finally passed by the state legislature in 1956.

VIEWED FROM THE WEST BALCONY, THE MAIN CONCOURSE WAS COMMERCIALIZED UNTIL THE METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY INTERVENED.

The act empowered localities to create special zoning or land-use protection for historically or aesthetically distinguished places. “As time marches on,” wrote Francis Keally, past president of both the Municipal Art Society and the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, “it behooves all of us to keep a watchful eye on any changes that would affect the aesthetic possessions of New York, and, when necessary, our voices should be heard in combating any such attempts to destroy the cherished remembrance of the past.”

In April 1963, before the demolition of Penn Station began, Wagner formally endorsed the recommendation of his committee and named a 12-member Landmarks Preservation Commission. The commission came too late for Penn Station, though, prompting the New York chapter of the architects institute to lament, “Like ancient Rome, New York seems bent on tearing down its finest buildings. In Rome, demolition was a piecemeal process which took over 1,000 years; in New York demolition is absolute and complete in a matter of months. The rise of modern archaeology put an end to this kind of vandalism in Rome, but in our city no such deterrent exists.” Two years later, the city council overcame the objections of real estate developers and codified a permanent commission armed with police power and the right of eminent domain. The law also provided tax abatements to hard-pressed property owners.

THE MAYOR’S TEMPORARY COMMISSION had already identified 700 sites that were considered valuable enough historically or aesthetically to be preserved. Community Planning Board No. 5 in Midtown voted overwhelmingly against landmark status for Grand Central, but surprisingly little controversy was generated at a commission hearing on May 10, 1966. Three witnesses appeared in favor. Virtually the only opposition was mustered by lawyers for the railroad itself. Robert Tinsley, representing the Municipal Art Society, unabashedly proclaimed the terminal “the most magnificent railroad station in the world.” He described it as “purely an American building bearing the full stamp of the American Renaissance” and said Jules Félix Coutan’s sculpture on the 42nd Street façade “is the best of its kind of the 20th Century anywhere.”

Another speaker, William Lynn McCracken Sr., of Staten Island, referred the commission to a 1959 essay by Henry Hope Reed. In his The Golden City (a book that Jacqueline Onassis described as “like finding a long-sought friend or mentor”), Reed waxed rhapsodic about the “colossal Mercury who motions to us to view the splendor that transportation has created” and unequivocally concluded, “No Picturesque Secessionist terminal can even attempt to rival the Grand Central or any other of our great classical terminals, because today’s designer refuses to recognize the theatrical, nay, operatic, qualities of art.”

Methodically working its way through hundreds of potential sites deemed worthy of preservation, on August 6, 1967, the permanent commission declared 11 structures—including Carnegie Hall, Hamilton Grange, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Highbridge Park water tower, and Grand Central Terminal—New York City landmarks, bringing to nearly 200 the structures it had designated during its first two years. Grand Central was described as “a magnificent example of French Beaux Arts architecture; that it is one of the great buildings of America, that it represents a creative engineering solution of a very difficult problem, combined with artistic splendor; that as an American Railroad Station it is unique in quality, distinction, character; and that this building plays a significant role in the life and development of New York City.”

The terminal “evokes a spirit that is unique in this city,” the designation added, and “combines distinguished architecture with a brilliant engineering solution, wedded to one of the most fabulous railroad terminals of our time. Monumental in scale, this great building functions as well today as it did when it was built.” Grand Central, the commission concluded, “always has been a symbol of the city itself.”

But the terminal’s reprieve was only temporary. Within a few weeks, the beleaguered New York Central was inviting architects to submit plans for a 2-million-square-foot building as tall as 45 stories atop Grand Central’s main waiting room.

BY THEN, the New York Central was virtually bankrupt and was running out of alternatives to generate revenue. The railroad had already wantonly commercialized the terminal by monetizing every square inch it could (including the Colorama, which was billed as the world’s largest photograph transparency, and the 13.5-foot-diameter replica of the Westclox Big Ben clock over the south concourse). The clutter manifested itself in nonmaterial ways too. In 1949, the railroad experimented with daily canned Muzak broadcasts from more than 40 loudspeakers and accompanied by 240 commercials over 17 hours (which netted the railroad $1,800 a week, against what it said was then an $11 million annual deficit to operate the terminal).

Leading the charge against the audio intrusion was Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, who figured that any interference with people’s ability to concentrate on a book or magazine was bad for business—his. “If they get away with this, nobody will be able to read on any means of conveyance in the United States,” he complained.

Appearing before a state Public Service Commission panel, the railroad’s lawyer challenged Ross’s assertion that the broadcasts made his ears ring. He was asked whether his own hearing was good. “It is perfect,” Ross testified. “It is too good. Under the circumstances I am thinking of having an ear drum punctured.” Ross denied that he had urged the magazine’s readers to complain, but the railroad lawyer produced a “Talk of the Town” item that exhorted readers to do just that. To which Ross, unfazed, replied: “I beg your pardon, I guess I must have read that in Grand Central Terminal.”

At the hearing, James F. Johnson, a former Secret Service agent, recalled how he had lost his ailing mother-in-law in the terminal because his wife became befuddled by the hubbub, which was compounded by the fact that the paging service had been discontinued in favor of lucrative commercials. James L. Fly, a former chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, declared that “the forced feeding of advertising” destroys a listener’s right not to listen. Harold J. Harris, a psychiatrist, cautioned that the noise pollution could unleash behavior triggered by “suppressed rage.” Another witness, Virginia L. Rowland, warned of even more dire consequences. “It is not too fantastic,” she testified, “that one of those employed in the terminal might go berserk and start shooting up the customers.” A month later, the Central capitulated, halting the broadcasts and acknowledging, without saying so in as many words, that its experiment was unsound.

BUT IF COMMERCIALS weren’t enough to drive away passengers, long-distance rail travel was doomed by airplanes and the construction of a concrete web of interstate highways. Railroads were under assault, especially passenger service, which couldn’t compete and which the lines subjugated to more profitable freight. (Robert R. Young, the Central’s chairman, memorably observed that until 1946, pigs huddled into freight cars could cross the country without changing trains, but passengers could not.) The Central’s passenger revenues plummeted from $135.5 million in 1948 to $106.5 million in 1954 and a mere $55 million a decade later.

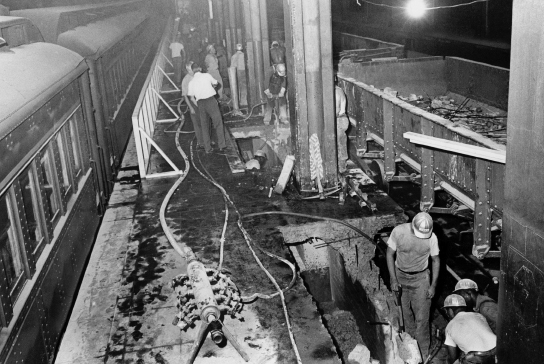

NINETY-FIVE COLUMNS WERE SUNK INTO BEDROCK 55 FEET BENEATH PARK AVENUE FOR WHAT BECAME THE PAN AM BUILDING.

“I live in the twilight of railroading, the going down of its sun,” E.B. White wrote in 1960. “For the past few months I’ve been well aware that I am the Unwanted Passenger, one of the last survivors of a vanishing and ugly breed. Indeed, if I am to believe the statements I see in the papers, I am all that stands between the Maine railroads and a bright future of hauling fast freight for a profit.”

Moreover, while automobiles and airplanes achieved dazzling speeds, the trains he rode to and from New York and his farm in Maine maintained their “accustomed gait” of just over 30 mph. “This is an impressive record,” he concluded. “It’s not every institution that can hold to an ideal through 55 years of our fastest-moving century.” The Pennsylvania Railroad was in a similarly precarious position. Real estate ventures like Penn Plaza, which replaced Penn Station, and the Pan Am Building had bought time for the railroads but were insufficient to cover mounting costs and diminishing revenue. On February 1, 1968, the unthinkable happened. A worst-case scenario loomed as the only remaining option for survival. The New York Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad merged to form the Penn Central. The combine, which became the country’s biggest real estate company and the owner, through Madison Square Garden, of the New York Knicks and the New York Rangers, would last two years before declaring bankruptcy itself—the nation’s largest. (In 1976, the railroad was folded into Conrail, which was created by the federal government to run failing freight lines; the former Penn Central Corporation morphed into American Premier Underwriters, part of Carl Lindner’s American Financial Group.)

By then, the Long Island Rail Road, which the Pennsylvania had controlled since 1900, would have been sold off to New York State for $65 million. New York and the Connecticut Transportation Authority would buy or lease the Central’s tracks from Grand Central to Connecticut and pay Penn Central to operate the commuter service. A similar arrangement would produce Metro-North in 1983, leading Joseph R. Daughen and Peter Binzen, who wrote The Wreck of the Penn Central, to conclude, “Thus, close to a quarter of a million commuters in the nation’s largest city ride trains that are state owned or are heavily subsidized by public agencies. If this isn’t ‘nationalization’ it is something quite close to it.”

FIVE MONTHS AFTER THE MERGER, the new company proposed building a 55-story cast-stone and granite slab designed by Marcel Breuer and developed by Morris Saady, which, as the builders described it, would be “floated” above Grand Central and rise 150 feet higher than the Pan Am Building. One design called for the tower to be cantilevered above the terminal to preserve the façade. An alternative would raze one side of the terminal to create a uniform front but preserve the Main Concourse. The tower known as 175 Park Avenue would generate at least $3 million annually for the Penn Central from air rights alone. Neither version was embraced by city officials or by many prominent architects.

“Horrible—terrible,” said Richard Roth, who was the principal architect of the Pan Am Building. “We put the Pan Am Building way back from the main part of the terminal, replacing an ugly structure over the train shed. It formed a gracious backdrop for the terminal itself.” Architect Philip Johnson declared the proposal an “outrage,” adding, “I was against the Pan Am Building, against the idiotic idea of putting bowling alleys in the waiting-room space when that was brought up a few years ago, and I’m against this new thing. It’s wrong in every possible way.”

The City Planning Commission had no jurisdiction because the proposed building did not require any zoning variances. That didn’t stop Donald Elliott, the commission chairman, from pronouncing the proposal “the wrong building, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.” Ada Louise Huxtable weighed in a few days later and was no less unequivocal. She called Breuer’s blueprint “a bizarre scheme that could only be conceived in and for New York.” Worse still, it created a heads-they-win, tails-you-lose dilemma. “Designation by the Landmarks Commission does not insure preservation,” she acknowledged. “All the railroad has to do is show that the building is enough of a losing proposition to prove ‘hardship’ under the landmarks law and permission must be given to demolish after certain procedures have been satisfied. This is having your landmark, but taking a certain calculated risk of dooming it.”

In one version or another, the historians James Marston Fitch and Diana S. Waite later wrote, “The Breuer scheme had several architectural merits and two insuperable drawbacks.” The merits, such as they were, included the preservation of the concourse, the waiting room, and the façade. “But,” they wrote, “the negative aspects of the proposed alteration are profound and are ambiental in nature”—that the tower would suck up all the air from the remaining sky space and place an impossible burden on already overloaded public transportation.

On September 20, 1968, under its chairman, Harmon H. Goldstone, the landmarks commission rejected the developer’s claim that the project would have “no exterior effect.” That touched off a full year of verbal jousting and counterproposals—including a promise by the developer to preserve the Main Concourse if the commission allowed him to construct the tower. (The commission’s jurisdiction extended only to the exterior.)

On August 26, 1969, the commission voted 8 to 0 to deny the Penn Central permission to mongrelize the terminal. Its rejection of a certificate of appropriateness derided the two plans as so massive that they “would reduce the landmark itself to the status of a curiosity” and declared that “to balance a 55-story office tower above a flamboyant Beaux-Arts façade seems nothing more than an aesthetic joke.” The second alternative was even worse, the commission concluded. “To protect a landmark, one does not tear it down. To perpetuate its architectural features, one does not strip them off.”

Moreover, the commission said that the terminal’s aesthetic value had to be considered in its physical context in a city that, unlike Paris, had few “dramatically terminated vistas.” Echoing V.S. Pritchett, the commission wrote that New York had “Trinity Church at the end of Wall Street, Washington Arch at the foot of Fifth Avenue and the RCA Building at the end of the Rockefeller Center gardens. Yet none of these have the sweep that Park Avenue still provides for the Grand Central Terminal from the south.” To mitigate any hardship claim by the railroad, the commission empowered the Penn Central to transfer the air rights to other developers at nearby sites.

Instead, less than two months later, the Penn Central sued.

THE RAILROAD ARGUED in the State Supreme Court in Manhattan that the commission’s rejections were unconstitutional because they went “beyond the scope of any permissible regulation and constitute a taking of plaintiff’s private property for public use without just compensation.” The suit, seeking $8 million for each year development was delayed, even challenged the landmark character of Grand Central as “highly debatable and at best doubtful.” “The aesthetic quality of the south façade is obscured by its engulfment among narrow streets and high-rise buildings,” the Penn Central’s lawyers from Dewey, Ballentine, Bushby, Palmer & Wood contended. “It is hardly seen at all except for a short distance to the south on Park Avenue, and even there the view of the façade is intersected by the encircling roadway and by the tall buildings that line Park Avenue. Furthermore,” the railroad’s lawyers argued, in what amounted to a stinging architectural indictment of the Penn Central’s earlier air rights venture, “the terminal is set against the backdrop and contrasting lines of the Pan Am Building, which appears to hang over the terminal and to dwarf it.” (This argument was a little like the defendant accused of parricide begging for mercy because he is an orphan.)

A RARE VIEW OF THE REAR OF THE TERMINAL AS THE STEEL FRAMEWORK WAS BEING INSTALLED FOR THE PAN AM BUILDING.

The Municipal Art Society intervened as a friend of the court and mustered a veritable who’s who of legal talent on behalf of Grand Central. (Among those who contributed to the society’s brief were former mayor Wagner, and other legal luminaries, including Bernard Botein, Whitney North Seymour Sr., Francis T.P. Plimpton, Samuel I. Rosenman, and Bethuel M. Webster.) A trial was conducted before Justice Irving Saypol, who would take more than two years to deliver his decision. (Saypol was perhaps best known for having prosecuted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for espionage conspiracy in 1951, a case in which he had decided the defendants were guilty nearly a year before the jury rendered its verdict.)

Saypol invalidated the Grand Central designation, delivering a second blow to the landmarks law in less than a year (the designation of the J.P. Morgan mansion on Madison Avenue had been voided the previous July by the state’s highest court, the Court of Appeals). He declined to address the constitutionality of the statute but ruled that by preventing the railroad from earning rent on the air rights for the proposed tower, the commission created “economic hardship” which “constitutes a taking of property.”

He also concluded that a city compromise, which would have permitted the transfer of air rights from Grand Central to the adjacent Biltmore Hotel site, was uneconomical. Ada Louise Huxtable wondered whether the delay had been a blessing in disguise, given the downturn in the city’s real estate market. “Did Penn Central and the developer really lose all that money they are claiming damages for (that will help sink the city), or did the city’s delaying action perhaps save their shirts?” After two years of “municipal breath holding,” those questions, she suggested, finally would be addressed in an appeal of a case so disturbing because of “the gravity of its effect on the city’s heritage.”

But while Deputy Mayor Stanley M. Friedman said the city was “99 percent sure” to appeal the decision, an appeal, it turned out, was by no means certain. In fact, the city’s chief lawyer was arguing against it. Without ruling on the constitutionality of the law, Saypol had delivered a thinly veiled warning to city officials that designating a landmark did not come without cost. “The point of decision here,” he wrote, “is that the authorities empowered to make the designation may do so but only at the expense of those who will ultimately have to bear the cost, the taxpayers.”

That cautionary note was not lost on W. Bernard Richland, the city’s corporation counsel. With the Penn Central claiming that landmarking the terminal had cost it $60 million so far, Richland was worried that the city, already verging on a fiscal crisis of catastrophic proportions, would be liable for damages. Richland recommended to Mayor Abraham D. Beame that the city not appeal Saypol’s decision.

“Bernie wanted us not to appeal,” John Zuccotti, the former chairman of the City Planning Commission, remembered. “He had some thought that we were exposed. He was very concerned. I remember the Penn Central people coming to see us and they urged us not to appeal, too. We debated the issue in front of Abe and he said appeal.” Exactly what changed Beame’s mind may never be known. But by the time he reviewed the subject with Zuccotti and Judah Gribetz, a deputy mayor, he had received a poignant appeal from Jacqueline Onassis.

THE LEGAL APPEAL—and the threat that the city would fold—galvanized a pantheon of prominent New Yorkers, spearheaded by the Municipal Art Society. Frederic Papert, Ashton Hawkins, and Brendan Gill, all ardent preservationists, figured prominently (Gill was succeeded as architecture critic at the New Yorker by Paul Goldberger, who later wrote that while Gill “alone did not save Grand Central Terminal, he did as much as anyone to establish the climate that made that possible, through his writing and his civic activism and his behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing”). Gill had been Grand Central’s guardian for decades. In 1958, he railed against a “living billboard”—a platform over the ticket windows on which fashion shows were staged—and warned that Madison Avenue’s hidden persuaders “will eventually find a way to make those twinkling constellations spell out your favorite smoke, like a constellation should.” At Gill’s memorial service in 1998, George Plimpton said: “The only things Brendan hadn’t been able to save in his lifetime were the Polo Grounds, Ebbets Field, the Maisonette, Alger Hiss, the Reichstag, the Edsel, and the passenger pigeon.” The preservation movement had other heroes, too, including Dorothy Miner, who was the landmarks commission lawyer.

If Jacqueline Onassis needed any prodding, she got it from her good friend Karl Katz (a board member of the Municipal Art Society, he took her to an exhibit he designed at Grand Central to dramatize the potential demolition of the terminal), and possibly from Babe Paley, whose husband, Bill, had advised Beame’s predecessor, John V. Lindsay, on urban design (Babe Paley’s involvement would have been poetically just; she was a descendant of Commodore Vanderbilt). Laurie Beckelman, who answered the pivotal phone call from Onassis (and would later go on to become chairwoman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission), passed the phone to Kent Barwick, the Municipal Art Society president, at its tiny offices on East 65th Street. “I took the call and it was unmistakably Jackie,” Barwick recalled. Papert, a former Kennedy advance man, later recruited her to the Municipal Art Society board, where she would diligently advocate on behalf of Columbus Circle, St. Bartholomew’s Church, and other preservation projects. (In 1982, she publicly planted a kiss on City Comptroller Harrison J. Goldin’s cheek, which was said to have sealed his vote to save Lever House.) Her handwritten plea to Mayor Beame dated February 24, 1975, probably carried the day for Grand Central. She appealed to his nobility, recalled how much President Kennedy had intervened to block a federal office building in Washington’s Lafayette Square, how he loved Grand Central, and added plaintively:

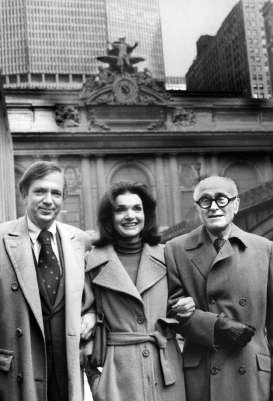

FRED PAPERT OF THE MUNICIPAL ART SOCIETY, JACQUELINE ONASSIS, AND PHILIP JOHNSON JOINED TO SAVE GRAND CENTRAL.

Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? If they are not inspired by the past of our city, where will they find the strength to fight for her future? Americans care about their past, but for short term gain they ignore it and tear down everything that matters. Maybe, with our Bicentennial approaching, this is the moment to take a stand, to reverse the tide, so that we won’t all end up in a uniform world of steel and glass boxes.

“HAVE I GOT A CASE FOR YOU,” Bernie Richland told Nina Gershon, a senior appeals lawyer in the corporation counsel’s office, once he was persuaded to pursue the appeal. Gershon, who would later be appointed to the U.S. District Court in Brooklyn, said that once the decision to appeal was made, the city was gung-ho:

There were some in the preservation community who questioned the city’s resolve to pursue, through appeal, the fight to preserve Grand Central Terminal as a landmark, after a devastating loss in the trial court, which had not only rejected, with derision, the findings of the Landmarks Preservation Commission regarding the significance of the Terminal but found that the designation of the Terminal as a landmark was unconstitutional; ominously, the trial court had also severed and kept open the request for damages for a “temporary taking.” But when Bernie became convinced of the merit of the city’s position, he did not stint in his support of the appeal.

Preservationists made their case before the Appellate Division of the State Supreme Court and in the court of public opinion. Onassis joined with Philip Johnson, Mayor Wagner, Bess Myerson (the city’s former consumer affairs commissioner), the author Louis Auchincloss, Thomas P.F. Hoving (the Metropolitan Museum of Art director), Representative Edward I. Koch, and Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton, among others, on a star-studded Committee to Save Grand Central Station. “Europe has its cathedrals and we have Grand Central Station,” Johnson had declared, on January 31, 1975, at a press conference. Diane Henry wrote in the Times, “Although the audience cheered Mr. Johnson’s eloquence, it was most fascinated by the presence of Mrs. Onassis, who rarely lends her presence and name to a public cause.”

IN DECEMBER 1975, the Appellate Division reversed Saypol. In a 3 to 2 ruling signed by Presiding Justice Francis T. Murphy, the appeals panel wrote that the only question before it was whether the Penn Central had persuaded the court that the law “as applied to them in this case, imposes such a burden as to constitute a compensable taking. Put another way, while the exercise of the police power to regulate the private use of property is not unlimited, it is for the one attacking such regulation in any given case to establish that the line separating valid regulation from confiscation has been breached.” Penn Central’s burden, the court said, “is to establish that they are incapable of obtaining a reasonable return from Grand Central Terminal operations, not that they are not receiving it.” The court concluded that the burden had not been met.

“Structures such as the Brooklyn Bridge, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Public Library and Grand Central Terminal are important and irreplaceable components of the special uniqueness of New York City,” the judges wrote. “We have already witnessed the demise of the old Metropolitan Opera House and the original Pennsylvania Station. Stripped of its remaining historically unique structures, New York City would be indistinguishable from any other large metropolis… The need to preserve structures worthy of landmark status is beyond dispute; and the propriety of the landmark designation accorded Grand Central Terminal is essentially unchallenged.”

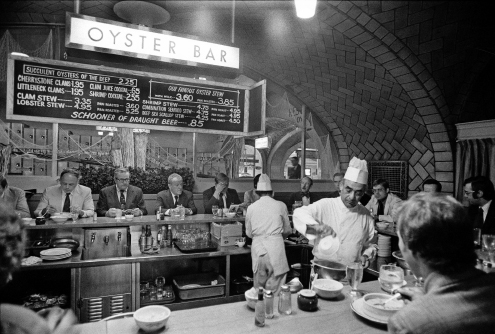

ENJOYING LUNCH AT THE OYSTER BAR OF THE OYSTER BAR. NOTE THE VAULTED CEILING, AT RIGHT, AND THE 1974 PRICES.

The judges were more than wary of Saypol’s warning that landmark designations may be made only at taxpayers’ expense: “Such language suggests that any regulation of private property to protect landmark values constitutes a compensable taking. Such holding would surely, as the amicus brief submitted hereon states, ‘eviscerate New York’s Landmarks Preservation Law.’ ”

Eighteen months later, in a case argued by Gershon’s successor, Leonard Koerner, the Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, again affirmed Grand Central’s status as a landmark. When times are flush, seizing landmark properties by eminent domain and compensating the owners might be desirable or even required. But, the judges concluded, especially when a city is in financial distress, “it should not be forced to choose between witnessing the demolition of its glorious past and mortgaging its hopes for the future.”

The preservationists’ victory parties were short-lived. Penn Central appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. When the Court heard oral arguments on April 17, 1978, advocates chartered an eight-car Landmark Express (including Car 120, the vintage Pennsylvania, which played host to first-class passengers at the turn of the century) to make the round-trip from New York to Washington, where they were met by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. “A big corporation shouldn’t be able to destroy a building that has meant so much to so many for so many generations,” Onassis said. “If Grand Central Station goes, all of the landmarks in the country will go as well.” She added, “If we don’t care about our past, we cannot hope for the future.”

The stakes were enormous, for preservationists and for property owners. Ada Louise Huxtable was driven to hyperbole by this point, warning that everyone except “the Penn Central and some unreconstructed real-estate types” considered the proposed piggyback tower that would render Grand Central “the filling in a Pan Am–office tower sandwich” to be “architecturally and environmentally revolting.”

PENN CENTRAL TRANSPORTATION CO. V. NEW YORK CITY was the first case in which the High Court considered historic preservation. The Court issued its decision on June 26, 1978. The 6 to 3 opinion by Justice William Brennan affirmed the New York Court of Appeals ruling that landmarking was constitutionally within a municipality’s police powers and that this designation in particular did not constitute an indefensible “taking” of property by the government. “The designation as a landmark not only permits but contemplates that appellants may continue to use the property precisely as it has been used for the past 65 years: as a railroad terminal containing office space and concessions,” the court concluded. Brennan wrote:

The Landmarks Law no more effects an appropriation of the airspace above the Terminal for governmental uses than would a zoning law appropriate property; it simply prohibits appellants or others from occupying certain features of that space while allowing appellants gainfully to use the remainder of the parcel.

The Landmarks Law, which does not interfere with the Terminal’s present uses or prevent Penn Central from realizing a “reasonable return” on its investment, does not impose the drastic limitation on appellants’ ability to use the air rights above the Terminal that appellants claim, for, on this record, there is no showing that a smaller, harmonizing structure would not be authorized. Moreover, the pre-existing air rights are made transferable to other parcels in the vicinity of the Terminal, thus mitigating whatever financial burdens appellants have incurred.

Justice William Rehnquist wrote for the minority that the Landmarks Commission’s refusal to sanction the tower above the terminal violated the Fifth Amendment’s ban on taking private property for public use without just compensation. “The City of New York, because of its unadorned admiration for the design, has decided that the owners of the building must preserve it unchanged for the benefit of sightseeing New Yorkers and tourists,” Rehnquist wrote.

“JACKIE ONASSIS WILL SAVE US,” Philip Johnson had predicted, and no one involved in saving Grand Central doubted that her presence and eloquence contributed mightily to the public groundswell that undergirded the verdict and to subsequent victories by preservationists. “Jackie, the great arbiter of good taste in fashion, food and architecture, raised the consciousness of the nation to the importance of historic preservation,” wrote Roberta Brandes Gratz, an architectural historian. “The implications of Penn Central for advocacy are so great,” the architecture critic Paul Spencer Byard wrote, “that the public perception will shift from seeing preservation as a matter of pleasure to seeing it as a public necessity.”

But the court victory was partly Pyrrhic. After all, as Rehnquist wrote, the city does not “merely prohibit Penn Central from using its property in a narrow set of noxious ways. Instead, appellees have placed an affirmative duty on Penn Central to maintain the Terminal in its present state and in ‘good repair.’ ”

Problem was, the Penn Central was bankrupt.