NO. 93 IN POLICE INSPECTOR Thomas F. Byrnes’s encyclopedic Professional Criminals of America was named Peter Lake. He was described as five feet seven, weighing a stout 165 pounds, with graying black hair and dark hazel eyes. He typically sported a bowler, rakishly cocked. His arrest record dated roughly to 1870, and while he was accused as many as 50 times after then, he was seldom convicted. In 1886, Byrnes described Lake, better known as “Grand Central Pete,” as “one of the most celebrated and persistent bunco steerers there is in America, ‘Hungry’ Joe possibly excepted.” (“Hungry Joe” Lewis famously swindled Oscar Wilde while he was on a lecture tour in New York in 1882, prompting Byrnes to remark unapologetically that Wilde, who “reaped a harvest of American dollars with his curls, sun flowers and knee-britches,” was no less a swindler then Lewis, “only not quite so sharp.”)

Peter Lake (his name would be evoked in Mark Helprin’s novel Winter’s Tale) earned his moniker by loitering at the depot looking for arriving rubes. He found yet another one as late as 1907, prompting the Times to opine about Pete and his fellow bunco artists:

Of late years confidence games of far larger size than these worthies ever attempted have monopolized public attention, but people with good memories can recall when New York could get quite excited over a little thing like the beguilement of a pocketbook containing $32.87 from a rustic visitor. But, though such exploits have lost their zest through cruel comparison with the achievements of high, or higher, finance, it seems that they are still the limit of “Grand Central Pete’s” humble ambition. Not only is he still attempting them on his old hunting ground; he is succeeding with them quite in the old way. And this despite the fact that he is now 72 years old!

By the time Peter Lake died in 1913, the same year that the new Grand Central opened, some would see poetic justice in the fact that the House that Vanderbilt Built was immortalized in the nickname of the nation’s number-two-ranked con man, who was considered “so tough that his spit bounced” and is credited by some with the maxim “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

DURING ITS FIRST CENTURY, Grand Central has witnessed the arrival and departure of celebrities, of draftees on their way to military training, and of kids going to summer camp. Walter Prendergast, a deputy city sheriff, estimated in 1940 that over the two decades that he had been escorting prisoners to Sing Sing on the Ossining train, at least 135 of them were executed. The terminal has often been defined, too, by its anonymous regulars, the stereotypical passengers whose billions of footfalls at rush hour have burnished the Main Concourse’s Tennessee marble floor. For all the well-earned encomiums bestowed on the terminal’s physical being, its character has always been shaped by the people associated with it: the commuters and the travelers who arrived or departed for the long haul; the avuncular conductor who’s been greeting the same passengers for decades; the black-shirted Ecuadorean shoe shiners in the Graybar Passage who, like the redcaps before them, work at menial jobs to pave the way for the first generation in their families to attend college.

The muted whispers and full-throated roars of people speaking to themselves or greeting friends collectively form the cacophonous voice of the Main Concourse, and that voice, David Marshall wrote in the mid-1940s, “born of a thousand human lips and the shuffling of a thousand human feet upon marble, is never still. Never a buzzing sound, not even a roar, it’s a wide-open, spacious sound like the autumn wind in a forest, or the sea breaking on the rocks; and through it runs—unnoticed by the tone-deaf and the unobservant—a rich variety of overtones, a kind of accidental music that forever achieves little patterns and loses them again; a wild, fugitive music, like the tune fragments that race through the ringing of the rails and the clicking of wheels over the joints.”

RUSHING TO CATCH A TRAIN might strike some people as pedestrian. To others, it is a mesmerizing daily ballet that defies the linear foundation of train travel and the street grid outside. (Trains, Thane Rosenbaum, a Fordham law professor, once wrote, are perfect for type A personalities. In contrast to buses, a train “runs on a track, rarely deviates from a straight line, operates entirely with tunnel vision and is primarily goal-directed as it races to get its passengers to their next appointments.”) Alastair Macaulay, the Times’ dance critic, analyzed the choreography:

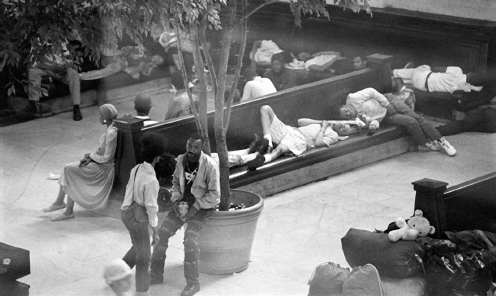

BEFORE THE 1990S, COMMUTERS ALTERED THEIR CHOREOGRAPHY ON THE CONCOURSE TO SIDESTEP THE HOMELESS.

Before 8:15, almost everyone is in motion, part of one busy stream or another: it’s populous but remarkably quiet. Between 8:30 and 10, movement and stillness are continually juxtaposed: a good many people are stationary—waiting, watching, handling luggage, standing in line for tickets or information, making calls on their cellphones—adding a strong element of visual contrast to the still flowing, though lessening, lines of human traffic. By 10, the hall has largely become a tourist site, with more than 10 people at any one moment taking photographs. Although passengers certainly still come and go, they no longer dominate… Between 8:30 and 10 a.m., enough people stand still, some in groups, to make the floor look like an Italian piazza: those painted by Piero della Francesca come to mind. Earlier, a dancegoer could easily feel the resemblance between the incessant streams of people and the first movement of Jerome Robbins’s ballet “Glass Pieces,” but now the view recalls the scene in the Mark Morris work “L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato,” where, amid the crisscross of four horizontal lines of walking people, a stationary man and woman spot each other. At times the scene recalls the urban vortex of Busby Berkeley’s “Lullaby of Broadway.” And any Cunningham devotee will recall urban studies like his “CRWDSPCR,” in which the movement of one human being is circumscribed by that of others.

By the evening rush, people are descending the Met Life escalators into the concourse, Macaulay wrote, but not just their direction was reversed.

Body language has altered plenty during the day: there’s a much less economical variety of dynamics, speed and behavior. You now notice many different mixtures of legato, staccato and marcato in the way people walk, and a new liveliness in the way they stand; even those walking briskly now are able to multitask (looking to and fro, consulting phones, rubbing their faces).

All of them look less reserved, as if they’d gotten a load off their chests during the day, but also less touching and less polite; people now are more volatile, funny, sexy and open. (Downstairs the spectrum is ever larger: people run for trains, talk helter-skelter while waiting for them, eat meals.) They aren’t more beautiful or characterful than before, but they’re more animated and communicative. Only on the down escalators do people merge into one single current now. The early morning showed just one facet of city life, but by late afternoon the station reflects the diversity of the city as a whole.

In more than a century, Peter Lake was among the few characters whose given name was so closely associated with Grand Central, although others could claim that their affinity for the terminal was more than skin-deep. Take Jay Hogan, for example, a railroad enthusiast from Durham, Connecticut. In 2004, after winning a $50 gift certificate from a tattoo parlor, he had the Roman deities atop the terminal’s façade replicated on his back.

Over the years, others have enjoyed more tangential connections to the terminal, among them Gregory Pantazi, a West Side restaurateur who in 1921 became the latest, but undoubtedly not the last, sucker to fulfill Peter Lake’s credo. Pantazi paid $1,200 to two con men to “buy” Grand Central, which has probably been “sold” almost as many times as the Brooklyn Bridge. In 1929, according to urban legend, a debonair gentleman who introduced himself as T. Remington Grenfell, the vice president of the Grand Central Holding Corporation, offered two fruit sellers, Tony and Nick Fortunato, a lease that would allow them to transform the information booth into a branch of their greengrocery. The Fortunatos delivered a check to the imposters ($10,000 by some accounts, $100,000 by others), but when they showed up to renovate the booth—on April 1—they discovered they had been duped.

Passengers arrived with dreams, some dashed with a sudden dose of reality, and others fulfilled, with a little help from the railroad. In 1928, 15-year-old Leonard Lucarello of Union City, New Jersey, whose father was an iceman, ventured into the terminal with $350 he claimed to have borrowed from his father’s business and tried to buy a ticket to Hollywood, where he figured he would be the next Rudolph Valentino. The Travelers Aid Society returned him home. There is no record that the young man ever made it into the movies.

In 1984, Tom Byrne, the assistant stationmaster, let Peter Getz make an announcement that reverberated over the public address system in the cavernous concourse: “Attention Helen Swiggett. Please go to the information booth. There’s a boy there who wants to ask you to marry him.” They were wed a year later.

SELLING HAS ALWAYS BEEN ASSOCIATED with Grand Central, whether some huckster was unloading the terminal itself on an unsuspecting sucker, promoting his own prospects to potential employers in the Big City, or pitching retail to passengers and passersby. Grand Central’s oldest tenant is the Oyster Bar, which opened below sea level off 42nd Street even before the terminal did. Viktor Yesenky was hired by Union News to run the Oyster Bar on opening day and didn’t retire until 1946. (Abe Mendel, who had a restaurant in the old station, passed up the space because it seemed too remote.) Distinguished by Rafael Guastavino’s vaulting tile arch ceilings, the restaurant exemplified faded elegance by the time Jerome Brody, who transformed the Four Seasons, the Rainbow Room, and other glittering eateries, was approached to run it, in 1974. “Its oyster stew had become famous, but the rest of the menu could best be described as ‘continental,’ ” Brody later wrote. The place had been closed for two years. “With the decline of the long-haul passenger train system,” he recalled, “came the decline of the restaurant.” People no longer came to Grand Central to dine (they now do again). The marble columns had been wallpapered and painted aquamarine and the 500-seat restaurant had gone bankrupt. Brody took a chance and turned it into a destination and, aw shucks, the Oyster Bar says it sells 5 million bivalves a year. (The Oyster Bar is now employee owned; Marlene Brody, Jerome’s widow, is the franchiser.)

Speaking of selling, Steve Kivel is the third generation running Central Watch, off the 45th Street passageway. His grandfather founded the business in 1952, and Kivel is now the terminal’s second-longest tenant. “I’ve been here my whole life,” said Kivel, who is in his early 40s and commutes daily from Westchester on the Hudson line. “I have literally grown up in Grand Central. The terminal has changed from somewhere you pass through by necessity to an actual destination. Our store is tiny, but we manage to make the most out of every square inch. I always compare it to working in a submarine. The rent has certainly changed over the last 60 years, but so has the price of everything else.”

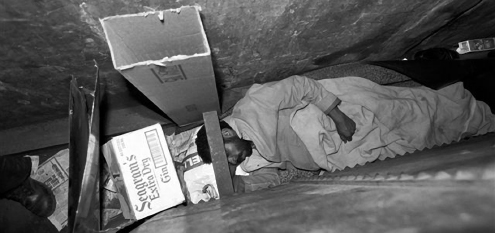

AS MENTIONED EARLIER, one reason the terminal closed at night was to keep the homeless from congregating there. Herding everyone out obviated the need for special treatment, for better or for worse, of people who sort of reverse-commuted in the 1980s from panhandling and other pursuits. They came home each night to Grand Central to sleep in overlooked crannies or squat in unused railway cars. Metro-North temporarily reopened the terminal at night when the temperatures fell into the teens but reversed the gesture after reported crime rose.

The homeless, like the commuters, were easy to stereotype, but each had his or her own story. There was Madeline, who became homeless when her grandmother died and who said she “saw the opportunity to be secure in Grand Central, to be secure for the rest of my life.” She liked “the quality of people” there. Asked about Penn Station, she scoffed, “There’s just no comparison.”

DURING THE 1970S AND 1980S, THE MAIN WAITING ROOM BECAME A HAVEN FOR THE HOMELESS.

Lee was a 55-year-old former car cleaner who apparently lost his job because he drank too much. He collected veterans’ benefits when he could but was found most of the time near the shuttle entrance. There was Mama, a hunched panhandler who spoke little English and perched on a milk crate off Vanderbilt Avenue; she helped hand out clean clothes from the Salvation Army to young homeless women and rolls provided on the sly by a terminal bakery. She died of pneumonia on Christmas Day 1985; a volunteer named George McDonald saved her from potter’s field. McDonald was inspired to create the Doe Fund, which emphasizes self-sufficiency for the homeless and fields a force of hundreds of Ready, Willing, and Able street cleaners.

Louis Napolitano was a transit police officer working the graveyard shift. His job was “get ’em up and keep ’em moving,” but in his anti-loitering duty he also came to realize that “the longer you’re here, you see it’s just people trying to survive.” He became a one-man outreach team, steering the homeless to permanent shelter and abiding by his own “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy (“After closing, don’t come out where people can see you”). So did Bryan Henry, a Metro-North cop for 24 years until he retired in 2009 as a lieutenant. “From my perspective, it was simple,” he said. “If you really care about a person, they sense it, and respect was the currency of the street.”

“MOLE PEOPLE” SECRETED THEMSELVES IN THE TUNNELS BENEATH THE TERMINAL, EMERGING TO PANHANDLE.

Henry, who earned a degree in urban studies at Fordham while he was on the force, said he identified with the homeless because he left New York as a young boy to live in Jamaica in the Caribbean and then returned when he was 8. “I went through culture shock twice,” he said. “That culture shock parallels people who are experiencing homelessness and a disconnect from the mainstream.” Henry said he was inspired by Walking a Tightrope, a book about Eastern philosophy. “In Buddhism, as one approaches enlightenment, one of the stages you go through is to be compassionate,” he said. “It’s my own personal philosophy to reach out to people that are less fortunate than I am.” He added, “I’m constantly walking a tightrope. On the one hand, I’m trying to be compassionate. On the other hand, I’m trying to do my job as a police officer and make the terminal safe.”

NOBODY IS SUPPOSED TO LIVE AT GRAND CENTRAL, but the terminal has been a second home to many employees, some of whom go unnoticed or just taken for granted. Others became legendary, celebrated as familiar beacons in a sea of anonymous faces—like Mathilda Taylor, manager of a newsstand, whose cat Mutzi was the terminal’s favorite feline, and Lizzie Duryee, owner of a tiny shop that sold “every imaginable dress and accessory dear to the feminine heart and indispensable to the feminine peace of mind,” but best known for the daily aphorisms she placed in her shop window.

In 1947, Fred Wright retired as a Pullman porter after 55 years of service, which started in 1892 when he was a water boy for the railroad at the age of 12. In the late 1940s, Rodney Cole, known to terminal employees as “Keys,” was still working as a locksmith in Grand Central, as he had been for nearly two decades. In an era before coded security cards, his skill at defeating stubborn mechanisms or compensating for lost keys was legendary, earning him a reputation as a magician—a particularly appropriate distinction, since he had also assisted Harry Houdini in repairing the trick locks on his “escape-proof” trunks, which could be opened from the inside without a key.

In 1953, Jacob Bachtold, a Swiss émigré, retired at the age of 77 after 50 years of, well, clock watching. Known as “Jake the Clock Man,” he had supervised the terminal’s 1,000 or so clocks, a particularly onerous challenge twice a year because of daylight savings time. He had been hired by the Central in 1903 as an electrician and stable foreman for the six draft horses that spun the roundhouse turntable. Bachtold could have gotten a nice watch, but instead the railroad graciously presented him with a gold pass good for any run. And speaking of clocks, in 2009, Falt Watch Service and Repair closed its office on the third floor of the terminal, where it had operated since about 1930 and served as an official inspection site for railroad employees, who were required to present their watches for testing once a month.

In the 1950s, Ralston C. Young, a redcap, conducted noontime prayer meetings four days a week in a coach on Track 13. In 1956, Sigismundo Rienzi retired as a dining car steward after 40 years, during which, someone figured, he seated the equivalent of the entire population of Philadelphia. That same year, Raymond Oliva retired as a baggage handler. He served every president from Theodore Roosevelt to Dwight Eisenhower. An Italian immigrant, Pietro Ierardi, who arrived in New York penniless in 1880, was so diligent at polishing shoes at Grand Central that when he finally checked into a sanitarium in Stamford, Connecticut, in the late 1920s, a court accounting discovered he was worth $175,000.

Stephen T. Kelly, a retired manager of Grand Central, worked for the railroad for four decades. Once he allowed the Main Concourse to be transformed into a ballroom on New Year’s Eve 1963 for a benefit. “Thirty-seven years a railroad man,” he said. “And yesterday I had to go downtown to get fingerprinted for a cabaret license!”

For decades, Billy Keogh melodiously cried out the arrival times of trains and their tracks, as revealed by the Teletype at his fingertips. But while live announcements still are made periodically from the stationmaster’s office—in addition to recorded warnings about unattended packages or watching the gap between the trains and the platform—train departures are not routinely announced with the proverbial “All aboard” (the way Daniel Simmons, the legendary train announcer at Penn Station, did). That’s because most trains regularly leave on the same track, and, because they are not passing through as they would in a station, there is typically more time to board. (The “voice” of Grand Central belongs to Daniel Brucker, who joined Metro-North as a press secretary in 1987 and is now the terminal’s irrepressible manager of tours. He described his dulcet tones as “sort of like the distant voice from the past—one that you’d hear coming from your Dumont television set, intoning about the marvels of power steering, awaiting you in your brand new 1952 DeSoto.”)

OFFICER PETER CHAMBERTIDES (LEFT) WITH BRYAN HENRY, WHO RETIRED AS A LIEUTENANT IN 2009 AND WAS KNOWN FOR HELPING THE HOMELESS.

In 1967, Lester Onderdonk of Hastings, who hailed from an old railroad family, was replaced by a 59-by-11-foot electric billboard installed over the ticket booths to display the arrival and departure of trains. He wasn’t pleased with other people’s notion of progress, which eliminated the jobs of three railroad employees who had wielded chalk to post the times on a blackboard in the waiting room under Vanderbilt Avenue. “I hope that when they plug in the new system, when it is finished in a week or two, the whole thing blows up,” he told a reporter. It didn’t, but the electromechanical board was eventually succeeded by rows of flipping panels for each letter and number (a version was immortalized at the Museum of Modern Art), and the flip board was replaced by another innovation from Solari Udine of Italy, liquid crystal display modules.

Progress, of sorts, also eliminated another job, Mary Lee Read’s. She was the terminal’s organist beginning in 1928 and presided from a console on the east end of the Philosophers’ Gallery. Once, she was suddenly inspired to interrupt a Bach piece to play “What a Friend We Have in Jesus”—twice. Two years later, she told the New Yorker in 1947, she was informed that a man who had been walking through the station on his way to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge heard her performance. “It was his mother’s favorite hymn, and he stopped and listened to it,” she recalled. “It just broke his heart. Instead of jumping off the Brooklyn Bridge, he went to Cleveland and organized a mission.” Read was touted as the only organist in America expressly forbidden to play the national anthem. The last time she did, during the evening rush on December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, pedestrian traffic froze. Commuters missed their trains. She continued to play holiday favorites in the weeks preceding Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter through the mid-1950s. (Read’s fan base rivaled that of Gladys Gooding, a fellow organist immortalized as the answer to a trivia stumper: Who was the only person who played in the same year for the Knicks, the Rangers, and the Brooklyn Dodgers?)

Five-foot-five Timothy P. Curley, a conductor, has regaled commuters on the 82-mile run north to Wassaic with local history and pop psychology as a former Transcendental Meditation instructor. One passenger recalled the time a bunch of rowdy prep school kids were acting out next to an elderly lady. “And he went up to the kids,” the passenger remembered, “and he said, ‘Is this lady bothering you?’ And they immediately got quiet.”

Harry Kelly, the stationmaster, grew up in the Bronx and has worked at Grand Central since 1973. He’s responsible for 600 cleaners, custodians, ticket sellers, and craftsmen who work in the terminal. Also in 1973, when he was 21, Robert Leiblong, who commutes from Brewster, started working as a trackman to pay off his college loans. Later, he earned a master’s degree in engineering and became Metro-North’s senior vice president for operations, supervising a staff including 850 conductors and assistant conductors (165 of them women), 600 engineers who drive the trains (including 20 women), and 60 rail traffic controllers, among the more than 5,000 employees who maintain the trains and tracks.

Some alumni can’t get enough of Grand Central. Edward G. Fischer joined the New York Central as a messenger in 1908, when he was 15, and rose to become the stationmaster known as “Mr. Courtesy.” He kept a framed aphorism in his office that defined courtesy as “a little thing with a big meaning.” Fischer retired as stationmaster in 1958 after a 49-year stint with the railroad but returned a year later as a part-time news dealer. “I love this place like a second home,” he said. “I just couldn’t stay away.”

REDCAPS have been among Grand Central’s most visible employees and, legend has it, they began there. James H. Williams, the son of a slave, who began his career as a doorman at Thaley’s Florist Shop on Fifth Avenue, was hired as a porter (their caps define them as “attendant”) when the force included 25 whites and two blacks. He worked his way up to chief in 1909 and served 45 years, until his death in 1948 (when there was only one white redcap, Milton Newman, left). Along the way, Williams encouraged young black men to work their way through college as baggage handlers (“Do not tip the Red Caps,” early timetables advised passengers). Some accounts say that he originated the redcaps when, as an enterprising teenager one Labor Day, he fastened a piece of red flannel to his hat as a signal that he was available to help with luggage, according to Eric Arnesen’s Brotherhoods of Color: Black Railroad Workers and the Struggle for Equality.

A SMALL ARMY OF REDCAPS SERVED PASSENGERS.

Whatever the origins of the name, the distinctive cap caught on across the country. Williams, who always wore a white carnation in his lapel, “raised the dignity of carrying bags from something to do when there is no other job to that of public service, a job of self-respect requiring men of the best caliber,” the playwright Abram Hill wrote in 1939, when redcaps were making about $2,000 a year, tips—typically a dime—included. “He has proved that the old superstition that Negroes would not work under a Negro is false.” The Chief was well-known to generations of New Yorkers and visitors, including youngsters who needed to borrow money to get home after a costly weekend in the city. “ ‘Jim will take care of you at the terminal’ is a phrase many a young New Yorker has heard from his father and mother,” one biographer wrote.

The civil rights leader Lester B. Granger worked as a redcap under the Chief, recalling what amounted to a postgraduate education at Grand Central as he “roamed the paved stretches of the station’s labyrinths, chasing down travelers with bags as a beagle hound chases a rabbit.” When Williams died, Granger wrote,

remembering him with great affectionate sorrow will be ‘Grand Central Alumni’ from New York to California, and from Miami to Seattle. These former students of the Chief are, many of them, successful professional and businessmen, most of them with a tendency toward flat feet and ulcers. But one and all, they will acknowledge their terrific debt to Chief Williams, for he had the kindly wisdom to keep open at Grand Central a generous supply of jobs each year for Negro college students. He had the judgment to rule them with a rod of iron. But rule them as he might, he liked them and believed in them, and they today are grateful to him.

Williams commanded a small army of 500, of whom, he once estimated, 100 were attending college and another 25 were graduates. Samuel Battle, who became New York’s first black police officer, was a redcap under Williams. In 1927, Williams’s son Wesley was hired as the city’s first black firefighter. Another son was a college president. When he died, Elizabeth Eckard, who supervised the Travelers Aid Society, said, “We can’t run Grand Central without the Chief. He’s as much a part of the place as the Twentieth Century.”