A WEEK BEFORE CHRISTMAS IN 1945, my mother took me and my brother Tom on a trip from Brooklyn to the place that she once described as Oz: Manhattan. I was ten, my brother two years younger. The war was over, and so was the Depression (although we knew almost nothing about what that word meant). We were going to see Santa Claus. At the place where our father’s favorite newspaper, the Daily News, was made.

That meant we had to change subways at least twice, crossing platforms, hurrying upstairs and down, and making our way to the Lexington Avenue line, which would take us to 42nd Street. Our final train was packed, the cars hurtling through the tunnels with a kind of squealing ferocity. And then we joined the crowd emptying the car, heading up still more stairs, and out through a last door.

“Wait,” my mother said. “I want to show you something.”

And she led us into the largest indoor space I had ever seen. There were people moving across shiny marble floors in many directions and a gigantic clock with four sides, and a large board with numbers and the names of cities. A deep voice kept speaking from somewhere, talking about times and tracks, the voice echoing off the gleaming walls. We were in a place called Grand Central Station.

There were soldiers there, too, in heavy military coats, and a few sailors in pea jackets. Late arrivals from the war. They all carried duffle bags, but were not in any military formation. They came upstairs from somewhere, some of them wide-eyed and astonished, and they pushed out into the crowd of the immense building. Looking, turning, squinting. And the immense murmur of the crowd was cut open by screams. Screams of joy. Screams of delight. A woman, always a woman, came bursting forward, almost leaping, some with kids tagging behind them, kids younger than Tommy and I were then. The soldier and the woman, the sailor and the woman, embraced each other. Sobbing. And we saw an older man off on the side, suddenly erect, saluting. And then another. And another. And then a young soldier on crutches was there, hauling his bag behind him. And there was nobody to meet him. He just stood there. Staring around him. Looking lost. The trouser of one leg folded and pinned above his knee.

My mother went to him, to ask him if he needed help. And the three of us led the one-legged soldier to the counter beneath the four-sided clock. A woman behind that counter listened, nodded, pulled a microphone close, and began speaking into it. We could hear the message: “Could the party meeting Corporal Jennings please come to the clock in the center of the terminal?” Years later, I still remembered the name. Jennings. And how, when my mother turned away from him, I saw tears in her eyes.

A MONTAGE OF 22 PHOTOGRAPHS 118 FEET WIDE WAS UNVEILED IN DECEMBER 1941 ON THE EAST WALL.

We went on to the old Daily News building, with the gigantic globe in the lobby, and there, beyond many hundreds of kids and parents, was Santa Claus on a kind of throne. I don’t know anymore what toy he handed to me or my brother. I remember vaguely the Christmas music playing in that amazing lobby, and I remember that we ate in a glorious automat, full of the sound of nickels rolling into small trays, and the aromas of fresh bread and coffee. But when we returned to Brooklyn, what I remembered most of all was that gigantic, almost golden room, the clock, the constant movement of strangers, and the men home from the war. In particular, the soldier on crutches, because he had only one leg. Just like my father, who had lost his own left leg after a soccer game in 1927, three years after he arrived from Ireland.

In all the years that followed, Grand Central, not Times Square, was for me the center of Midtown Manhattan. It still is. A place full of arrivals and departures, of sad farewells and new beginnings. A place charged with time, in the constant presence of clocks and changing schedules and looming appointments. Three decades after I first saw it, I was working for the Daily News, climbing subway stairs, with the energizing urgency of passing time driven by the imminence of deadlines. But it was also a place of rewards too, when the deadlines were met: the magazine shops, the Oyster Bar, the places full of bread and croissants to carry home.

In this wonderful book, Sam Roberts, another alumnus of the Daily News, tells me many things that I did not know until now about the layers of time in Grand Central. Here are the visionaries who imagined it, the pragmatists who made the visions real, the great craftsmen and workers who transformed it into such a huge, majestic, and glorious fact. Not simply a New York fact. A real, surviving part of the country itself. In novels, poems, and movies, it is woven into the American imagination. Sam Roberts reminds us that in Grand Central the palimpsests have palimpsests. Unveil one buried layer of the story and there is another layer underneath.

He also reminds us of the bad times in Grand Central’s century-long narrative. The rise of domestic airlines, with rapid service on jets to cities once reached by rail, was an obvious part of the change in Grand Central. But there were also larger factors involved in what seemed to be a tale of steady, irreversible decay. By the 1960s, the economy of New York was changing too. Factories were closing. The commerce of the port was ebbing away. By the late 1970s, the garment district was shrinking. As the old manufacturing jobs vanished, welfare cases escalated, along with homelessness and heroin addiction. You could see panhandlers in Grand Central, and a general grunginess spreading, along with a certain level of fear. Or generalized anxiety. Too often a passenger on a train could not find room on a bench in the waiting room. The homeless seemed there to stay.

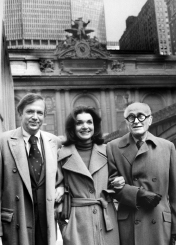

And yet, Grand Central would survive, and flourish anew. The story of its salvation is told in the pages of this book. It was driven by people who wanted to save it from the fate of Penn Station, which had been demolished. They had nothing to gain for themselves. They just wanted this enormous, once-beautiful piece of our lives to continue. One of the most important leaders of this movement was, of course, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who used her prestige and eloquence to get the message to a wide audience. Once again, a combination of visionaries and pragmatists made something glorious. Plans were drawn, and then revised; budgets were cobbled together, and then revised too; work started. But like most good things, it took awhile.

One Friday morning in the mid-1980s, before the last of the work was done, a fierce snowstorm hit the city. My wife was upstate with our car, in our hideout in Ulster County, so when I finished work I headed to Grand Central for the train. I just missed one, but, having no choice, I bought a ticket for the next one.

I wandered around the great main room of the station, looking for a bench where I could sip coffee and read a newspaper. There were no benches. They had all been removed to discourage their use as cots for the homeless. So I bought my coffee and went up the stairs at Vanderbilt Avenue, to watch the falling snow.

I was dressed for the weather, in a ratty ski jacket, equally ratty jeans, and boots and baseball cap. I had finished half the coffee when a woman came through the door from Grand Central, walked toward me at an angle, dropped a quarter into my coffee, and kept moving.

I laughed out loud.

She paused. “Oh,” she said, “I’m so sorry.”

“Forget it,” I said. “It was very kind of you.”

I poured the coffee out at the curb, retrieved the quarter, went back downstairs to the station, and gave the coin to a homeless guy.

Every time I go to Grand Central now, I think of that moment. And of the day, long before, when my mother led that baffled one-legged veteran to the information counter. Millions of people surely have other memories that are triggered simply by the mention of the name. If they read this book, they will think of many things they did not witness, or know. As I do now. Many of them are as grand as the place itself.