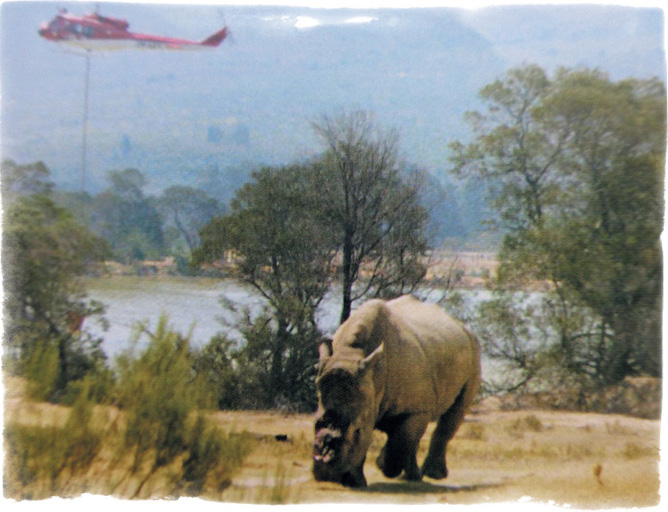

A fire breaks out at Fairy Glen after the attack.

A week after the attack Higgins and Lady were both still in an awful mess and had not yet reconnected with one another in the reserve. They looked strange without horns and the huge wounds on their faces were an ongoing reminder of the pain they were in. Flies were both a constant irritant and a danger, and one of the main tasks each day was to spray the wounds with a fly-deterrent.

A fire breaks out at Fairy Glen after the attack.

Higgins trips over his feet and stumbles as he moves away from the action at the dam.

Both animals had resumed eating and drinking, but they were driven in this respect by their instinct to survive; there was no pleasure in their grazing and their eyes spoke of pain, suffering, and confusion. Lady’s eyesight didn’t seem to have been affected too much by exposure to the sun’s rays, probably because she had been found first and her vacant, drugged, open eyes had quickly been covered with a wet towel. Higgins was found much later and the sun had rendered him almost blind. He seemed lost and appeared to have no sense of direction as he plodded wearily round the reserve, a long way from Lady. Pieter knew that the rhinos’ chances of recovery, and the speed of that recovery, would be greatly helped if he could get them back together. However, they were separated by nearly two kilometres, and both were preoccupied with their suffering.

Pieter now developed health problems of his own when he contracted chickenpox. Children often brush this illness off lightly but in adults it can be serious, and Pieter’s doctor told him to go to bed for two weeks and avoid exposure to sunlight. Three days later came another emergency call from Fairy Glen – the reserve was on fire. Jan, the reserve manager, told Pieter that helicopters were on the way to help put out the flames and advised him that everything possible was being done to rescue the situation. Bottie had taken over caring for Higgins and Lady on a daily basis so they were in good hands. However, as Pieter lay in his darkened room he thought of the near-blind Higgins smelling fire and not knowing which way to run. He also thought of the other animals being forced by the fire into the fences. He thought of the panic, the noise, the smoke and his animals. Tormented by his thoughts, he abruptly rose from his bed, dressed, got into his vehicle and headed for the reserve.

Four helicopters were circling Fairy Glen as Pieter hurtled through the gates, heading for his second emergency in a month. He saw that the animals were widely scattered as they tried to distance themselves from the flames and the smoke.

Bottie ran up to him as he pulled up at the lodge. ‘You’re crazy Pieter, the doctor told you to stay in bed. There are lots of us here, we can handle this.’ There is no-one in the world that Pieter trusts more but he had to know the answer to his overriding concern: ‘Where are Higgins and Lady? We must find them’.

Bottie knew that would be Pieter’s first question. ‘Lady is safe, and I’ve got the choppers looking out for Higgins.’ He had hardly finished speaking when his radio crackled into life and one of the helicopters reported that Higgins was near the dam. It was a relief to know where he was but it wasn’t good news. Higgins was virtually blind and would be highly stressed so he could easily run into the water and drown. The whole scene was chaos, with vehicles going in all directions, helicopters scooping water from the dam, and all the while the smoke and flames getting nearer. A calm animal with full eyesight would have been at great risk, but Higgins was sightless and traumatised.

They drove close to where the rhino stood. He was shaking his head and turning round in confusion. He ran a little way, tripped over his feet and stumbled. Pieter could see his wounds had reopened and blood was dripping from his face. Suddenly, the confused and terrified Higgins was no longer alone; Pieter hadn’t noticed Bottie get out of the vehicle and that he was now walking straight up to Higgins, talking to him as he approached. As he watched Bottie, Pieter thinks he probably stopped breathing – this was very dangerous.

Bottie got to about two metres from the rhino and stood there talking, then he turned his back and, still talking, walked away. Like a tame animal, Higgins followed and Bottie led him to safety. The risk had looked insane but, as Bottie explained later, he was fairly confident he could pull it off – and anyway, on the spur of the moment, he couldn’t think of anything else to do. ‘By then Higgins knew me, and I think had started to trust me. I had fed him, watered him, sprayed his wounds, and always talked to him whenever I was close. At that time he couldn’t see much at all so his sense of hearing and familiar sounds were his main guide. He knew my voice meant food, water, kindness and treatment. He followed me – I don’t think there was anything else he could do.’ Bottie paused and grinned; ‘Except charge me maybe!’

It was a long, hard day but by mid-afternoon the reserve’s main buildings were safe, as were the animals, so Pieter went back to bed.

Higgins and Lady had been a pair before the poaching, and Pieter, Bottie and Denis realised it was now vital that Higgins should know Lady was still alive; everyone was sure they would aid each other’s recovery. The fire and his lack of vision had combined to make Higgins’ recovery much slower than Lady’s. He kept walking into trees and bushes, and this repeatedly opened his wounds. He was a sad and pathetic sight and it wouldn’t have surprised anyone if he had decided simply to lie down and die. But, along with the urge to reproduce, the survival instinct is powerful in animals and he was not going to give up.

They are still rhinos, but strangely disfigured now without their characteristic horns.

Higgins takes a break in the cool sand.

There had been many failed attempts to reunite the two rhinos. Pieter, Bottie and Denis had collected Lady’s dung and taken it to Higgins, along with lucerne or hay she had been lying on, or any other material that might have held her scent. Once, they had managed to lead him down off the high ground to the road, to within 300 metres of Lady, who at that stage was near the dam. He couldn’t see her – and she hadn’t seen him; he wouldn’t cross the road and had turned back up the hill.

Almost a month to the day after the poachers’ moonlight attack, Pieter and Bottie tried again to bring the rhinos together. The thinking was that Higgins had followed Bottie during the fire so perhaps this tactic could be repeated, allowing Bottie to lead Higgins across the reserve and back to Lady. It was worth a try.

The two men sat in their vehicle and watched the wounded rhino for a few minutes, then Bottie got out, went to the back of the bakkie (pick-up truck) and took a handful of lucerne. Pieter watched as his friend walked slowly towards Higgins, talking as he went. It worked. Higgins followed the voice he had come to trust and even grabbed occasional mouthfuls of lucerne.

Pieter followed them slowly in the truck as the strange pair made their way across the reserve: a nearly 2m-tall human being followed by a hornless rhino acting like a domestic animal. Fairy Glen is relatively small but Higgins and Lady could hardly have been further apart: the distance between them was about two kilometres and it took the odd couple nearly five hours to make their way slowly across the reserve. Bottie hadn’t been expecting or prepared for such a long trek and was wearing only shorts, sandals, a T-shirt, and no hat. As the hours ticked by the sun took its toll and Bottie was getting badly sunburnt and his feet were sore and blistered.

Then, suddenly, Higgins stopped. He raised his head and sniffed the air, snorting and making soft mewing sounds. The noises seemed at odds with his bulk, but his body language had changed dramatically and he seemed newly charged with life. He carried on making these noises while casting his head about, allowing his nose to conduct its research.

Bottie backed towards the vehicle and he and Pieter watched and waited. Suddenly, Lady burst from the bushes and ran towards her mate; their heads met gently and they seemed to kiss while the two big men looked on with tears in their eyes.

There is a strong human tendency to interpret animal actions in terms of human behaviour and to attribute human emotions and feelings to animals. Perhaps animal emotions are, in fact, not so different from ours. Certainly in the case of Higgins and Lady, their recovery gathered pace as soon as they were reunited. Lady acted as Higgins’ eyes, and the once dominant and sometimes aggressive male now meekly followed his partner.

Immediately after the attack the wounds had been sealed with cotton wool and Stockholm Tar. It didn’t take the rhinos long to dislodge this and, after a couple more applications, the ‘tar’ was abandoned as a wound-sealing treatment.

A patented aerosol for drying out wounds and keeping them clean and free of flies was being used to treat the rhinos’ injuries. Apart from initially being startled by the hiss of the aerosol, Higgins was remarkably tolerant of his spray treatments – in fact, he even seemed to enjoy them. Lady, however, reacted quite differently. To quote Denis, ‘You had to have your running shoes on because she would charge you’. They worked out a tactic for spraying her that involved enticing her to the front of the truck while the sprayer was perched on top of the engine. This meant she couldn’t easily reach the sprayer and the truck could be rapidly reversed if she charged. As the days, weeks and then months passed, both rhinos regained condition and a measure of confidence.

Higgins and Lady find one another at last.

Despite following Lady closely, Higgins’ blindness meant that he often brushed past or into trees, bushes and other objects and opened up his wounds. Nevertheless, the wounds on both animals seemed to be healing. Some 14 months later, the skin had grown back across their faces. The wounds still reopened from time to time and then flies became a danger again but, apart from these accidents, the physical healing process seemed to be going as well as anyone could have expected.

Rhinos’ brains are wired for the presence of horns.

The physical wounds should eventually heal completely, but we will never know about the mental scars. What’s more, rhinos’ brains must be wired for the presence of horns and there are bound to be repercussions when they are removed. Rhinos use their horns for defence and to push away potential aggressors. Without their horns Higgins and Lady have no defence against other large animals, such as the elephants and buffaloes on the reserve, which have had to be placed in bomas to allow the rhinos to wander freely.

Twelve months after the attack Higgins was seen mating with Lady and everyone at Fairy Glen started hoping this grim story might have a happy ending. The gestation period for rhinos is 15–16 months and their babies are small, so Lady won’t show signs of pregnancy until close to delivery.