Hook-lipped or black rhinos are targeted as relentlessly as their white rhino cousins.

Rhinos – both black and white – have been hard hit by trophy hunters over the years. By the early 1960s, most of the remaining wild white rhinos (fewer than 500), lived in what is now the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park in KwaZulu-Natal. The white rhino species was saved from extinction largely through the efforts of South Africans Ian Player, vet Toni Harthoorn and other dedicated conservationists who campaigned during the 1960s to save the species. By the time Higgins was born the population had recovered to about 20,000 animals, but that was as good as it would get.

Hook-lipped or black rhinos are targeted as relentlessly as their white rhino cousins.

While white rhino numbers were at their lowest in the 1960s, the black rhino population was healthier, at up to 70,000. But by the end of the 1980s poachers had taken a terrible toll on black rhino numbers too: only about 5,000 remained, as estimated in 2013 by the IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group.

The official figure for the number of white rhinos poached in South Africa in 2000, the year Higgins was born, is seven. As he entered his teens 13 years on, that figure had risen to an alarming and staggering 1,004 in 2013: a white rhino was poached every 8 hours 45 minutes in South Africa during the year – nearly three animals a day!

The table below gives the poaching figures for white rhinos since 2000. At the time of writing (early 2014) the annual birth rate may not be keeping up with the numbers being killed by poachers. A recent census in the Kruger National Park indicated numbers may have fallen from an estimated maximum of 12,000 to a possible low of 8,400. If poaching continues to increase at its present rate, and if the tipping point hasn’t already been reached, it certainly soon will be – and then it will be downhill again towards extinction in the wild.

South Africa and Zimbabwe are the main sources of horn, and in recent years poaching in Zimbabwe has returned to levels not seen since the 1980s. At least 123 rhinos were poached in that country in 2008, which was the highest number recorded since 1987. The methods used and actions taken by many of the poaching gangs indicate military training, and the AK47 was a favourite weapon for Zimbabwe’s poachers.

It is worth noting that South Africa’s neighbours, Namibia and Botswana, are both less affected by poaching. Many people say these countries are better policed and have less corruption; and some point to the death penalty in Botswana as evidence of a tougher system with effective deterrents leading to lower crime rates.

POACHING INCIDENTS

White rhinos killed in South Africa

2000 – 7

2001 – 6

2002 – 25

2003 – 22

2004 – 10

2005 – 13

2006 – 24

2007 – 13

2008 – 83

2009 – 122

2010 – 333

2011 – 448

2012 – 668

2013 – 1,004

(The above are official figures released by the Department of Environmental Affairs)

In 1993, the People’s Republic of China announced a total ban on the sale, purchase, import, export and ownership of rhino horn. Shop owners, dealers and stockists were given six months to dispose of their stock. Perhaps most importantly, rhino horn was removed from the list of state-sanctioned medicines.

The Chinese measures worked and contributed to holding rhino poaching at relatively low levels until 2002, when there was a sudden fourfold increase on the previous year’s figures. This coincided with Vietnam becoming the world’s main user of rhino horn. By no means all rhino horn that ended up in Vietnam was poached: a significant proportion was acquired legally. Permits to hunt rhinos were issued to trophy hunters who then exported their trophies quite legally, covered by CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of wild fauna and flora) permits. By 2010, 70% of trophy hunters shooting rhinos in South Africa were Vietnamese.

These ‘legal’ hunts enabled unscrupulous operators to run rings around the law and made a mockery of CITES ‘protection’. The transformation of Vietnam’s economy since the end of the war with the United States has been dramatic. As with the other ‘Asian tiger’ economies, consumer spending power has risen and, as a result, some species of wildlife have suffered and come under ever-increasing pressure. One of the worst affected animals is the rhino.

In 1977 CITES imposed an international trade ban on rhino horn, yet in 1978 South Africa reported the export of 149.5kg of rhino horn to Hong Kong. Further indications of South African government complicity in rhino horn trafficking came in 1982 when Dr Esmond Bradley Martin published his book Run Rhino Run. The 149.5kg declared in 1978 was shown to have originated from the former Natal Parks Board. However, records in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan show another 860kg as having entered these countries from South Africa at that time.

At $65,000 a kilo, rhino horn is now worth as much as gold or cocaine.

The Natal Parks Board had been a major supplier of rhino horn but stopped selling it after 1978 in order to comply with the CITES ban. By the end of 1979 most South African provincial authorities were officially prohibiting the export of rhino horn. However, Japanese records show that in 1980, three years after the CITES ban, 587kg was imported into Japan from South Africa. The origins of this horn were thought to be Angola, Namibia, Zambia and Tanzania. Whatever the origin, South Africa was part of the routing and these records indicate the regrettable ineffectiveness of international agreements. As with all commodities throughout the history of both legal and illegal commerce, the reality is that whenever there is a demand there will be a supply.

PRINCE BERNHARD, THE WWF, AND EX-SAS SOLDIERS

In 1981, in discussion in Nigeria with the WWF’s president Prince Bernhard, Dr John Hanks – an internationally respected biologist and conservationist with a doctorate from Cambridge, and head of the WWF’s Africa programmes – had raised the issue of the extent of rhino poaching and its catastrophic effect on populations. The prince was dismayed to learn that millions of dollars were being spent on security, while very little was being spent on investigating those involved in the actual trade. Prince Bernhard indicated to Hanks that he would like to finance an exercise to track down and expose the smugglers. The prince stressed that he would fund this himself as he believed it was not appropriate that it be seen as a WWF project, or that the money go through WWF accounts. A noble and sensible approach but possibly also a naive one – the idea had come from the WWF president, and was progressed by its head of Africa programmes, so there was no way this exercise would ever be seen as anything other than something in which the WWF had a hand.

At the end of 1987 Hanks flew to London to meet Sir David Stirling, founder of the SAS (Britain’s elite army unit, the Special Air Services). Sir David was running a private security and intelligence company called KAS Enterprises, whose employees were almost exclusively ex-members of the SAS. KAS was eventually contracted to set up operations in southern Africa to investigate and expose the illegal trade in rhino horns. The exercise became known as ‘Operation Lock’ and ran for a few years under the control of the KAS managing director, Colonel Ian Crooke.

According to ex-South African security branch policeman Mike Richards, between February and July 1990 the Operation Lock team sold 98 rhino horns to smugglers. Throughout its time in operation there were claims that Operation Lock was dealing in ivory and rhino horn. If these claims are true it is likely the explanation would be that it was a necessary part of their intelligence gathering and infiltration operations. Whatever the excuse or explanation, it is astonishing that an outfit that had been put in place by senior figures in the WWF should be dealing in animal products.

In this shadowy world, inhabited by shadowy people comfortable living in the shadows, it is unlikely that full details of KAS operations and all those involved in them will ever emerge. We can be sure, however, that the WWF, and agencies in both the British and South African governments, must have had a good idea of what was going on.

There are those who believe that the end justifies the means and that Operation Lock had some success. It has even been claimed that Operation Lock was partly responsible for the reduction in poaching during the 1990s, although this was probably more the result of the Chinese ban in 1993.

There are basically two types of poacher: the simple, subsistence-level tribesman who is hunting for the pot or killing for someone else, and the sophisticated, highly resourced criminal using helicopters, dart guns and advanced communications equipment. Very often, of course, the former works for the latter.

Since 2003, as the number of rhinos being poached has grown, so has the corresponding number of Vietnamese ‘hunters’ coming to South Africa to hunt them in order to procure their horns as ‘trophies’. South African government records show that in 2003 at least 20 rhino horns were exported to Vietnam (there were nine trophies with both horns, and two single horns). In 2005 the figure was 12 trophies (24 horns); in 2006 the number had increased to 146 horns, in 2008 it went down again to 98, then 136 in 2009, and 131 in 2010.

This permitted hunting allows horns to be kept as trophies and exported by the hunter under the cover of a CITES ‘trophy certificate’. In the years between 2005 and 2010 at least 659 horns were taken in this way. Using average horn weights, this means that a staggering 2–3 tons of rhino horn were legally exported to Vietnam. This produces a black market value of between $200 and $300 million, while the trophy fees would have come to just $20 million. This is not just a legal anomaly, it’s a loophole through which you could fly a jumbo jet, and the profits are huge.

By 2012 the Vietnamese hunters had started to be replaced by hunters from Eastern Europe, notably from Poland and the Czech Republic. These new ‘sportsmen and -women’ are being recruited by the Vietnamese horn dealers, who offer paid-for holidays in South Africa in return for names on licence applications and the presence of the licence holders when the animals are shot.

The diplomatic bag has long been used by embassies to move sensitive items in and out of host countries. In strict Moslem states where alcohol is prohibited, the ‘dip bag’ has enabled diplomats to enjoy a glass of wine with dinner. So it is with rhino horn: the bag provides the opportunity to smuggle with impunity.

In mid-2008 Tommy Tuan was arrested by the police at a hotel in Kimberley. He had just taken delivery of a consignment and in his room they discovered over 20kg of horn, a handgun, ammunition and a large amount of cash. Tuan was using a car with diplomatic number plates and its registered owner was Pham Cong Dung, the political counsellor at the Vietnamese Embassy. Two years prior to this incident the police had obtained evidence that the embassy’s economic attaché, Nguyen Khanh Toan, was using the diplomatic bag to smuggle rhino horns out of South Africa to Vietnam. Dung’s Honda was impounded by the police but later returned after Dung had given the explanation that his car had been borrowed by Nguyen Khanh Toan.

THE MEANING OF CITES

The CITES treaty – controlling, limiting and banning trade in endangered species – is often hailed as being the only effective barrier between many species and their extinction. CITES Appendix 1 and II listings have had their successes in promoting sustainability but, as we have seen with rhinos, the system is open to abuse; and, without the conscientious compliance of member states, its effectiveness will remain limited. As long as the abusers (individuals, organisations and governments) can operate largely unchecked, CITES will remain an expensive good idea.

The CITES treaty originally came into effect in July 1975. South Africa was a founding member, China ratified it in 1981, Thailand in 1983, Vietnam in 1994 and Laos in 2004. This means that all the nations key to the rhino-horn trade are CITES members. The green movement has called CITES ‘the animal dealers’ charter’, and many animal rights activists claim it promotes rather than stops trade!

In 1994 South Africa proposed changing the white rhino CITES listing from Appendix I (threatened with extinction) to Appendix II (trade to be strictly regulated). The conference members allowed this and, as we have seen, ‘hunting’ operations eventually played a major part in supplying Vietnam’s horn market after 2003.

In November 2008, TV footage showed an embassy official receiving a number of horns from a known trafficker. The footage was shot outside the embassy and Dung’s Honda was parked close by. The person who received the horns was Ms Vu Moc Anh, who was the embassy’s first secretary. The ambassador told a newspaper that Ms Vu Moc Anh was helping friends and wasn’t involved in horn smuggling. Normally, Dung’s Honda would have been parked inside the embassy, and his explanation for its being parked outside was that he wasn’t using it that day. Vu Moc Anh was recalled to Hanoi to explain her part in the incident, and Dung left South Africa some while later. Despite the evidence that embassy staff were involved in handling rhino horn, no action was taken by the South African government, seemingly because it wanted to avoid damaging diplomatic relations.

The ‘Boere Mafia’ was a South African organisation allegedly involved in canned hunting (controlled hunting in a limited area, often using animals that have been bred for the purpose) and poaching. Members of the organisation were accused of various offences, including rhino-horn poaching. However, in October 2010 the case against them was dropped on the grounds that the charges stemmed from arrests made four years earlier, and the prosecution case was based largely on the questionable testimony of a convicted felon. (It is suspected that this witness was a member of the gang and was frightened into not testifying.)

Following a 15-month investigation called ‘Project Cruiser’ into another suspected poaching scheme, suspect Dawie Groenewald and accomplices found themselves facing 1,872 counts of racketeering, money laundering, fraud, intimidation, illegal hunting and dealing in rhino horns. Dubbed the ‘Groenewald Gang’, Dawie and his 10 co-accused (which included his wife, other professional hunters, veterinarians, safari operators, and a helicopter pilot) have so far managed to delay the hearing of their case.

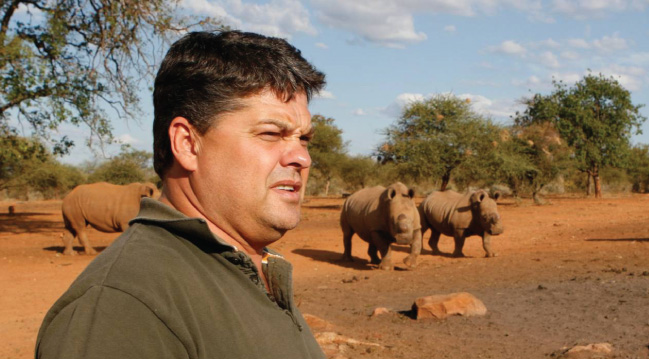

Alleged rhino horn syndicate ‘mastermind’ Dawie Groenewald on his farm near Musina, South Africa

Rhino organisations, sanctuary employees, conservationists and members of the public protest against rhino poaching at Johannesburg Zoo, November 2011.

The gang first appeared in court in September 2011 and there were subsequently a number of postponements. They again appeared in October 2012, and their counsel managed to obtain yet another delay until May 2013. In May it was decided that the case would be heard in the high court in Pretoria in July 2014. Some conservationists fear that the Groenewald Gang prosecution may end up going the same way as the Boere Mafia case, with charges either being dropped or greatly watered down.

The record of the South African authorities bringing successful poaching convictions is poor, and when convictions are obtained the punishment has often scarcely been a deterrent. However, when poachers appeared before presiding magistrate Prince Manyathi in 2010 and 2011, leniency was not shown for Xuan Hoang who was a Vietnamese courier caught at OR Tambo airport (Johannesburg) in March 2010. Manyatti gave him 10 years without the option of a fine. Then in 2011, suspected poachers Doc Manh Chu and Nguyen Phi Hung, who had been arrested at the time of the World Cup, also came before Manyathi. He convicted them and handed down sentences of 12 and eight years, once again with no option of fines. Conservationists, pro-wildlife activists and campaigners applauded the sentences.

Bilateral talks between South Africa and Vietnam took place in September 2011. It was announced that the parties had agreed to work towards an MOU (Memorandum of Understanding), which would include collaboration on wildlife protection, law enforcement and the management of natural resources. The MOU was eventually signed 15 months later on 10 December 2012.

Vietnam may have taken over from China as the world’s leading consumer of rhino horn, but Vietnam is by no means the only country involved in this trade. In the 1960s and early 1970s Hong Kong was a leading player; between 1970 and 1977 Yemen recorded receiving 22.5 tons of horn, which represented 7,800 dead rhinos; and Taiwan was also a significant consumer.

Today Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Hong Kong and Taiwan may not account for as much rhino horn as Vietnam, but all these countries are traders and/or consumers.

The Far Eastern consumers of wild animal products are not inherently bad people; they are only following beliefs and traditions that have existed for thousands of years. There are now reports that the consumption of shark-fin soup in China is decreasing. For many years campaigners such as WildAid and others have been working to increase public awareness of the realities of eating shark-fin soup. More recently, Chinese superstar basketball player Yao Min joined the campaign to ban the import and sale of shark fins. The cruelty, the unsustainability of supply (which could lead to extinctions) and other factors have been highlighted and, as a result, demand has fallen.

Shark conservation campaigners should not slacken their efforts but should be encouraged by this positive sign and continue to use these clearly effective methods to spread their message. The shark-fin example shows how public awareness and education in the Far East can be more powerful than military weapons and laws when it comes to reducing demand … and without demand there is no need for supply.

Jo Shaw of the WWF in South Africa commented: ‘… South Africa’s rhinos are up against the wall. These criminal networks are threatening our national security, and damaging our economy by frightening away tourists. Rhino poaching and horn trafficking are not simply environmental issues. They represent threats to the very fabric of our society.’ (Cape Times 20/01/14)