2

The Truth Is Within

Sometimes it is easier to recognize something than it is to define it. So it is with the loose association of beliefs, ideas, phenomena, and experiences variously labeled as “New Age,” “paranormal,” “supernatural,” “occult,” “unexplained phenomena,” “metaphysics,” “pseudoscience,” “mysticism,” and a host of other terms. Depending upon one’s personal definition, crystal balls, Bigfoot, ghosts, and palm reading are similar things; by other definitions they are vastly different. Adding to the confusion, researchers and retailers often label the same phenomena using different terms than do the general public. For example, scholars of religion often use the term “New Age” to refer to a social movement that started in the 1960s, which focused on the development of personal enlightenment and freedom from conventional thinking and religion.1 To the bookstores, New Age is simply a section in which employees shelve books on ghosts, the Loch Ness Monster, UFOs, psychic powers, Atlantis, and the like.

We do not wish to add to such confusion here by coming up with new terminologies, but we hesitate to use a term such as “New Age.” First of all, the term refers to a specific movement that emerged at a particular time. Further, it suggests that our phenomenon of interest is something “new.” This is hardly the case.

Consider the following tales:

Auxerre, France

Germanus and a few of his friends decided to have a little adventure, traveling the region around his town on foot so he could get to know the landscape and people better. Perhaps unwisely, they chose to begin their travels in the dead of winter and found themselves in a rural area with no place to stay on a bitterly cold evening. Running out of options, they entered a dilapidated building on the side of the road, which locals believed to be haunted. The building’s fearsome reputation did not bother Germanus, and he quickly drifted off to sleep. One of his fellow travelers was reading when he shouted an alarm. A specter was slowly rising up through the floor. At the same time, the walls were pelted by a shower of pebbles. The assailant was nowhere in sight. The alarmed traveler begged Germanus to protect him from the ghost. A deeply religious man, Germanus invoked the name of Jesus and commanded the spirit to provide its name and purpose. It told Germanus that he and a friend had been chained together and killed as punishment for some unrevealed crime, their bodies denied proper burial. The next day the men dug at a spot identified by the spirit and found two bodies tied together with chains. Germanus arranged for a proper burial, and the haunting ceased.

New York City

John was a charming and successful man, widely known as a person of great achievement, calm temperament, and careful reasoning. After the death of his wife, he became “withdrawn from general society; I was laboring under the great depression of spirits.”2 In his grief, he began reading about death and the afterlife, and sought the council of mediums. He soon began attempting to contact spirits himself, experiencing and meticulously documenting anomalous events such as the following:

During the last illness of my revered old friend Isaac T. Hopper, I was a good deal with him, and on the day when he died I was with him from noon till about seven o’clock in the evening. I then supposed he would live yet for several days, and at that hour I left to attend my circle, proposing to call again on my way home. About ten o’clock in the evening, while attending the circle, I asked if I might put a mental question. I did so, and I knew that no person present could know what it was, or to what subject even it referred. My question related to Mr. Hopper, and I received for answer through the rappings, as from himself, that he was dead! I hastened immediately to his house, and found it was so. That could not have been by any one present, for they did not know of his death, they did not know my question, nor did they understand the answer I received. It could not have been the reflex of my own mind, for I had left him alive, and thought he would live several days. And what it was but what it purported to be, I can not imagine.3

Seattle, Washington

Sara and her husband moved into a rental house near the University of Washington, sharing with an old friend, Jason, to save money. Sara fell in love with a room on the main floor; Jason happily took one of two rooms on the upper floor. About a month after they moved in, strange things started to happen. Sara was the first to get up in the mornings. Oftentimes while getting ready for work, she would hear the unmistakable sounds of someone walking down the stairs. The footsteps ceased at the landing, but no one was ever there. Sara learned to ignore the sounds, becoming flustered only when her two cats would on occasion stare and hiss at the stairs. She even put up with the lights in her bedroom, which sometimes switched on and off by themselves. The experiences were irritating but never menacing.

Jason was not so lucky. He worked a swing shift at a warehouse pulling orders for grocery stores. One evening he arrived home at around 11 p.m. and went up to bed. He had just turned off his light when he felt a weight at the end of the bed. In the darkness a hazy form slowly took shape near Jason’s feet. What looked like an old man with a hunched back was facing away from Jason, its head in its hands, seemingly distressed. As if it could feel Jason’s eyes upon its back, the “man” turned and looked directly at him. Jason shrieked upon seeing the wrinkled, balding visage with completely black eyes, and he flipped on the light. The spirit faded away, but an impression remained for several minutes where it had been sitting on the bed. Jason slept with a light on after that.

Although ghosts have been reported for at least three thousand years, the basic elements of such stories often remain the same, reflecting seemingly timeless human concerns.4 The belief that a ghost may result from a violent death or improper burial, or that the spirit of a relative might appear to warn of impending danger were favorites of medieval times and are still with us today. Indeed, the tale of Germanus occurred in 488 CE and the Germanus in question was bishop of Auxerre at the time, and is now a Roman Catholic saint. His traveling companions consisted of clerics under his command.5 Barring such details (and the anachronistic name), this story could easily pass for one that would be breathlessly reported on the latest television installment of Ghost Hunters.6

Meanwhile, the second story, concerning John W. Edmonds, highlights some noteworthy aspects of the religious movement that came to be known as “Spiritualism” in the United States. Edmonds was an accomplished lawyer and politician, elected to both the state house and senate, and later appointed to serve on the New York Supreme Court. Yet, after the death of his spouse and numerous spiritual encounters, he was forced from public service because he became an advocate for Spiritualism, for which he received considerable public condemnation—but also support from others—reiterating the simultaneously loved and loathed position of paranormalism in American culture. The above story is one of many experiences Edmonds recounts in his book making the case for the reality of spiritual phenomena and supporting the burgeoning movement sparked by the infamous “rappings” during the séances of the Fox sisters.7 Edmonds was a socially respectable firsthand witness, convert, and proselytizer for the movement.

Drawing on and then contributing to traditions of mesmerism, Swedenborgianism, Theosophy, transcendentalism, and New Thought, the Spiritualist movement popularized two enduring aspects of paranormalism: séances and professional mediums.8 Edmonds was one of the most respected evangelists of the Spiritualist movement, which was at the height of its popularity in antebellum America.9 Yet even a person of Edmonds’s standing was not above the penalties for publicly expressing belief in what would today be called the paranormal. The judge’s publication of Spiritualism (1853) led his own party to ostracize him from the judiciary, choosing not to renominate him for the state supreme court later that year, as he made plain in a letter to the New York Times, arguing it was a case of religious persecution:

I have your note in allusion to my position as a candidate before the Nominating Convention, in which you apprise me that while it was freely and fully admitted that my ability, integrity and judgment were beyond dispute, and that my judicial reputation was unimpaired, the prejudice against my spiritualism, alone, was noticed as a reason for declining to nominate me. I am not at all surprised at this. I am fully aware of the strong prejudice there is in the public mind against spiritualism in all its aspects. The manner in which my religious faith has been . . . assailed in the press, in the pulpit, and in private conversation, has left me no room to be ignorant of the state of public feeling on the subject. . . . I have not for a moment been unaware that I was thereby hazarding my position on the bench.10

Despite the condemnation and derision Judge Edmonds received in response to his advocacy for Spiritualism, upon his death in 1874, the Times noted in his obituary that “[t]he procession that followed the remains to the grave was one of the largest ever seen in this city.”11 Although Spiritualism as a formal movement lost steam with failed attempts by parapsychology to bring spiritual contact into the mainstream of twentieth-century science, the ideas championed by Spiritualists still haunt American culture.

It is very likely that you have heard stories like these before. Most people have a ghost story, if not more than one: an aunt, uncle, parent, grandparent, or other relative who claims a ghost sighting as a child, or a best friend who insists his home was haunted. Some of us have seen a ghost ourselves. As testament to the ubiquity of such tales, the last story above is from the first author of this book, when Christopher and his wife, Sara, shared a home with their friend Jason near the University of Washington in 1990.12

The Paranormal

Ghosts may be ever-present, but they are anything but new. Nor is astrology, or the belief in psychic phenomena, or even belief in the possibility of humanoid beings living in the woods. Many such beliefs stubbornly persist on the edges of society, believed in by many but never fully accepted. These beliefs often violate our taken-for-granted understanding of the “nuts and bolts” working of the world and mundane experience. They are not normal, but paranormal.

But what is paranormal? This question is remarkably difficult to answer, not least of all because the subject matter is often inherently ambiguous. Take ghosts, which exist somewhere between life and death, present and absent, material and ethereal, present and past, human and inhuman, and so on. Further complicating matters is the fact that, properly (in our view) defined, the “paranormal” is a cultural category that can shift across time and place, rather than being a fixed property of particular beliefs and experiences. Academics studying the paranormal have tended to focus on the rejection of the paranormal from institutional science.13 This is an important aspect of the paranormal to be sure, but also omits a critical feature of what becomes classified as “paranormal” by overlooking the role of institutional religions in defining what counts (in their view) as legitimate or illegitimate supernatural beliefs and experiences.

We can take some cues on this front from the man most responsible for creating the category of the paranormal as we know it today: Charles Fort. Fort was a voracious reader of newspapers and scientific journals, and he scoured publications from all over the world in search of anomalies. His first book centrally uses the religious metaphor of damnation to describe the realm of culture that would come to be known as the paranormal. The Book of the Damned amalgamates a variety of anomalies, which share the characteristics of rejection (damnation) by institutional science.14 Fort opens the text with: “A procession of the damned. By the damned, I mean the excluded. . . . The power that has said to all these things that they are damned, is Dogmatic Science.”15 The capitalization and designation of “Dogmatic Science” reveals Fort’s view that institutional science shares far more with religion than its advocates would care to admit. Or, more succinctly, “Positivism is Puritanism.”16 All of it merely accumulated acts of “Scientific Priestcraft.”17 Better yet, in his inimitable, contrarian style, Fort told readers: “I shut the front door upon Christ and Einstein, and at the back door hold out a welcoming hand to little frogs [falling from the sky] and periwinkles.”18

In short, “what Fort invented was our modern view of the paranormal . . . he tore down the hallowed traditions of religion and science.”19 In defining this realm of inquiry, Fort makes a remarkably sociological observation:

That anything that tries to establish itself as a real, or positive, or absolute system, government, organization, self, soul, entity, individuality, can so attempt only by drawing a line about itself, or about the inclusions that constitute itself, and damning or excluding, or breaking away from, all other “things.”20

Fort is unmistakably correct. In essence, institutional science, as the cultural arbiter of material reality, defines what is “natural,” and therefore within its investigative jurisdiction, and also by contrast what is “supernatural.”21

In addition, institutional science demarcates what topics and methods are considered legitimate within its boundaries by marking unwelcome practices, beliefs, and ideas that claim to be scientific as “pseudoscience,” which has been defined as “any cognitive field that, though nonscientific, is advertised as scientific.”22 Rooted in the Popperian tradition of the philosophy of science, a central feature of what institutional science advocates define as pseudoscience is non-falsifiability.23 Thus, there are two ways that institutional science plays a role in creating the category of the paranormal: first by defining what is “natural,” but also by damning beliefs and practices that claim to be scientific, such as creationism or cryptozoology, as beyond the pale of what is officially considered science. The examples of creationism and cryptozoology are instructive, showing that what gets banished from science can be taken up by advocates as either religion or the paranormal, depending on whether the rejected cultural domain falls within the bounds of organized religion or not.24

This leads to the second, typically overlooked dimension of how the paranormal gets defined as a cultural category. Despite academics’ focus on the importance of the role of science in defining the paranormal, there are two social institutions doing boundary work damning the paranormal. For topics designated as supernatural, organized religions hold (and compete for) cultural legitimacy. Social movements based on supernatural beliefs and (someone’s) intensive physiological and cognitive experiences, particularly trances, visions, and voices, must determine and adjudicate which supernatural beliefs and intensive experiences are to be considered “true,” and by contrast, which are to be considered, at best “false,” and at worst “the work of the devil.”25

An area where religion and the paranormal continually collide is in the realm of mysticism and extraordinary sensory experiences. In effect, science and “mainline” religions demarcate contemporary automatisms and “enthusiastic” experiences as supernatural and false; that is, not truly of supernatural origin. As scholar of religious experiences Ann Taves notes, “Supernaturalists, who could be secularizers when it came to false religion, understood true religion as particular, exclusivist, and revealed.”26 Meanwhile, sectarian and new religious movements attempt to harness the power of intensive physiological and psychological experiences, choosing particular varieties justified as true and condemning experiences other than those validated by the group as “of the devil.”27 Because higher-tension religious groups—those that impose stricter behavioral and ideological restrictions on their members—apply theological frames to the problem of what counts as “true religion,” sectarian groups demonize such experiences occurring outside their tradition. For instance, in 2007, roughly one out of five Americans agreed with the statement: “Certain paranormal phenomena (such as UFOs and Ouija boards) are the work of the devil.” As a result, demonology often becomes a cultural borderland between religion and the paranormal. Thus, where “supernatural” (or “superstition”) and “pseudoscience” are damnable categories for science, the “occult” and analogous terms are damnable categories for religion.28

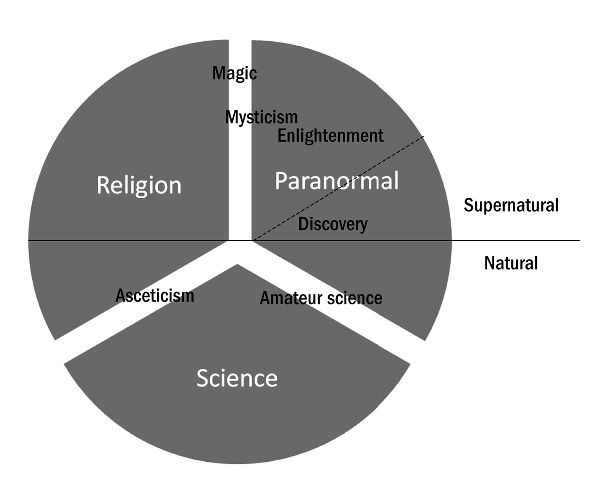

In contrast to defining religious and paranormal phenomena as the same, as many scientists do, or denying the similarities between “paranormal” and religious experiences, as many religious groups do, we instead advocate a bounded affinity theory of the paranormal that incorporates both the similarities between religious and paranormal beliefs and experiences, along with the cultural distinctions drawn by organized religious groups. The social processes demarcating experiences as natural or supernatural in origin, as well as those subsequent within religious subcultures designating such phenomena as true or false (or “of the devil”) mark a trail to what gets considered paranormal. From this perspective it is clear that the “paranormal” can be most usefully defined by accounting for its relations to both institutional science and religion.29

Despite our jest about bookstores earlier, the analogy works well here.30 If a prospective book buyer wants to read about a phenomenon that is at least partially understood and recognized by science, she should visit its respective section of the bookstore. The health and medicine section will have books on heart health, chemotherapy, and other topics “owned” by modern medicine. For information on investing, taxes, market conditions, or retirement, one must wander to the economics or business shelves. But if our shopper wants to read about a topic not currently recognized by scientists, she must hunt the fiction aisles for horror, fantasy, or science fiction, or browse the bookstore’s New Age and religion stacks. If the topic of interest is the resurrection of Jesus, healing through prayer, being “saved,” or another concept closely associated with Christianity or another world religion, the religion stacks are the best bet. Those scientifically dubious topics that are not tightly connected to mainstream religion, such as crystal balls, ghosts, and UFOs, fill the New Age shelves.31 Here one also finds books that might belong in another section were their topics to someday become accepted by science.32 Books on the healing power of crystals are consigned to the New Age section, waiting for a scientific discovery to facilitate a call-up to the legitimacy big leagues in the medicine section. Volumes that promote the power of positive thinking in acquiring fame and fortune sit here also, rather than in the business stacks.

Following what retailers already know, we group together a wide assortment of beliefs and experiences under a single banner labeled “paranormal.” Such beliefs and experiences are dually rejected—not accepted by science and not typically associated with mainstream religion in the United States.33 Thus, the belief that a crystal ball can foretell the future would be paranormal in nature, as would be the belief that an unidentified ape roams the Northwest woods.34 Both of these beliefs refer to unexplained phenomena and neither is associated with mainstream religion in the United States.35 Belief that Jesus Christ was resurrected from the dead would not qualify as part of the paranormal per this definition, since Jesus is associated with the majority religion in the United States—Christianity. The distinction is important, but we do not make it for theological reasons. Previous research and theory by sociologists, as well as our own research, indicate that believers themselves make this distinction. We realize that some people may combine elements from organized religion and paranormalism, but overall the distinction remains relevant. Figure 2.1 summarizes the categories of religious and paranormal phenomena.

|

Beliefs, practices, and experiences that are not recognized by science and not associated with mainstream religion |

|

|

Examples: Extrasensory perception, ghosts and spirit phenomena, astrology, crystal therapy, belief that extraterrestrials have visited earth, Bigfoot |

|

|

Religious Phenomena |

Beliefs, practices, and experiences that are not recognized by science but associated with mainstream religion |

|

Examples: Belief in the divinity of Jesus, belief in the power of prayer, faith healing, Satan and demons |

Figure 2.1. Definitions of the Paranormal and Religious Phenomena

As we will show, this definition of the paranormal makes sense of the empirical relationships between religiosity and paranormalism, and explains why different aspects of religion can hold negative, positive, or curvilinear relationships to paranormalism, depending on the cultural and empirical contexts under examination. This approach also recognizes and highlights the importance of the “paranormal” for disciplines engaged in studies of religion by locating each in relation to the intensive physical and psychical experiences that lie at the heart of both. Put simply, in contemporary Western societies, science delineates natural and supernatural, then religious groups divide religion from the paranormal.

Unfortunately, definitions are never perfect, and the paranormal rests on ever-shifting sands. Does a book on aromatherapy belong in the “self help” section or is it part of the paranormal? It depends on whom you ask. Does a book about visions of the Virgin Mary end up in the paranormal section or religion section? It often depends upon who published it or the perspective taken toward the material. A book from a Christian publisher that uses the Marian visions at Lourdes as a testimonial will be filed with the religion books. An author who discusses visions of the Virgin Mary as another manifestation of the same phenomena that produces faeries and ghosts, or that deemphasizes the Christian aspects of the Marian visions, may find her book filed under the paranormal.36 Indeed, books about angels are routinely found in both the religion and paranormal sections.37 It is also worth noting that advocates from some paranormal subcultures will be more closely connected to science or religion by virtue of how they frame their beliefs and practices. Many of the Bigfoot hunters we spent time with saw their pursuits as squarely scientific, while some the psychics or mediums we shadowed saw their practices and experiences as more akin to religion.38

We must also be clear that labeling of a belief, practice, or experience as “paranormal” is not meant here as judgmental or pejorative, at least on our part. It is possible that extrasensory perception (ESP) is a legitimate phenomenon that science is simply too stubborn to recognize.39 It is also possible that the many dedicated Bigfoot hunters will one day capture the beast, moving it from paranormal status to nature status in one fell swoop. But until and unless such things occur, Bigfoot and ESP will continue to inhabit the fringes. To express belief in such phenomena in certain circles may prompt scorn or concern about one’s judgment and even mental health.

I (Chris) took a tentative step into the world of the paranormal on a Saturday afternoon in December, to experience its dizzying array of beliefs and practices.

December: Anaheim, California

The Learning Light Foundation might best be described as a New Age learning center. The organization was founded in 1962 by a former Methodist minister named Walter Tipton. Disillusioned by organized religion, Tipton began seeking out “like-minded individuals” to gather for philosophical discussions about the meaning of life. At first, Walter and his wife, Lola, hosted groups at their home in Orange, California. The meetings quickly grew too large for their home and the group began gathering in a rented house. Membership continued to grow. In 1972, the group moved into a former Church of the Nazarene in Anaheim.40 The group’s mission is “[t]o provide quality education, training, and research for individuals to develop their fullest potential on all levels.”41

One of the educational opportunities provided by Learning Light is its biweekly Holistic Health & Spiritual Fair. The fair provides the opportunity for the general public to attend free classes, purchase items from vendors, book a healing session with an “energy worker,” or purchase a fifteen-minute session with one of the “readers” in attendance.

A Spiritual Cafeteria

Readers at the Holistic Health & Spiritual Fair claimed to provide services of great value, such as knowledge about one’s place in life, information about what the future holds, guidance for personal transformation, and spiritual meaning. Clearly, these are some of the same benefits offered by religious denominations, even if they might be referred to in different terms. Yet access to the benefits provided by a religious denomination often requires membership in the organization or at least some commitment to its beliefs. The paranormal, on the other hand, has a strong focus upon personal spiritual transformation over devotion to a particular belief or practice.42 Personal fulfillment and exploration trumps singular commitment.43 Those interested in the psychic realm can freely select from a variety of “tools” in their hunt for transformative experiences and may explore their interests via the media, by attending conferences, lectures, and fairs, or by developing relationships with psychics.44 It is as if some of those involved in the paranormal are walking the line at a spiritual cafeteria and piling on those beliefs and practices that most interest them at the moment.

An astounding buffet of products and services were available at the fair. I walked in the side door of the converted church, paid my $2 entry fee and wandered into the Learning Light Bookstore. Along one wall rested dozens of books about crystals, various forms of healing, angels, the mystical powers of dolphins, channeling, and how-to guides for developing psychic gifts. In the center of the room was a small table displaying crystals of differing sizes and price points. The strong smell of incense wafted through the building. Exiting the bookstore, I entered the sanctuary of the former church. Light shone into the room from a stained glass window of an angel high on the wall. Arrayed around the edges of the room were vendors selling various forms of incense and oils, more books and crystals, and various CDs and books on psychic powers and healing.

In the center of the room was a grid of sixteen tables. Some were empty, others occupied by the readers present at the event (see figure 2.2). Some sat alone, patiently awaiting their next clients. Others were in the midst of readings—some with their eyes closed, some shuffling through decks of cards, an older woman in the back grasping her client’s hands and loudly speaking in a strange voice. Many readers utilized objects to facilitate their readings including tarot cards, runes, astrological charts, and oracle cards (similar to tarot decks but without suits). Others retrieved information about their client’s past, present, or future by channeling discarnate entities, contacting the individual’s “spirit guide” and/or guardian angels, communicating with dead relatives, reading one’s aura, or, in two cases, even psychically contacting the client’s pet(s).

|

The reader claims to communicate with angels or other spiritual beings that are attached to or protecting the client. |

|

|

Animal Communication |

A reader who specializes in psychic communication with animals. Clients may bring a photo of their current pet and ask for help in understanding its moods or behavior. Or they may ask the reader to communicate with a beloved dead pet. |

|

Astrology |

Astrology assumes that the position of stars and planets at the point of one’s birth will have effects throughout life. The reader provides insight into one’s personality and information on how the current position of stars and planets will impact the near future. |

|

Aura Readings |

An aura is purportedly an energy field surrounding a person that can be viewed by psychics. It is believed that the colors of the aura will reveal characteristics of the individual. |

|

Channeling |

A channeler claims to receive or "channel" messages from discarnate entities, such as spirits, angels or elementals. Some channelers will claim to speak in the voice of the entity, others will simply relay any messages received. |

|

Clairaudience |

A reader who claims to be able to "hear" voices, music, or other messages from the spirit world. A clairaudient may claim to hear the voice of a dead relative when conducting a reading. |

|

Clairvoyance |

The reader claims to receive psychic knowledge about the past, present, and future through touch or feeling. |

|

Oracle Card Readings |

Unlike tarot card decks (see below) which follow a set structure, oracle card decks are idiosyncratic, with varying numbers of cards and differing themes. For example, the reader may utilize an oracle deck that consists of images of different angels. The reader intuits the meaning of each card as it is drawn. |

|

Past Life Readings |

A past-life reader claims to be able to intuit previous incarnations of the client. It is thought that difficulties in previous lives may cause problems or “imbalances” in this one. |

|

Psychic/Medium |

The reader who claims to receive information about the client’s past, present, and/or future through supernatural means, generally without the use of tarot cards, crystal balls, or other accessories. |

|

Psychometry |

The reader relays psychic impressions received from an object, such as a family heirloom. The reader may, for example, provide details about the meaning of the object to a deceased person. |

|

Reiki |

A massage/relaxation technique in which the masseuse alternates between physically massaging the client and manipulating the client’s “energy.” |

|

Runes |

The reader uses stone “runes” to intuit the client’s past, present, and/or future. The client may draw a single stone from a bag or the reader may throw the runes and interpret the resulting pattern. |

|

Tarot |

The reader uses a set of cards with stylized characters such as “The Fool” and ”Death.” The client or reader shuffles the deck and lays out a number of cards in a spread (numbers vary). The reader interprets the meaning and layout of the cards. |

Figure 2.2. The New Age Cafeteria: Services Available at the Holistic Health & Spiritual Fair in Anaheim, California (December 2015)

I immediately sat down in front of an unoccupied reader, who kindly informed me that readings were booked by buying tickets in another room. In the ticket room, a bulletin board displayed details about each of the readers. I booked readings with Shelley, whose skills were listed as “psychic/medium, intuitive Tarot, pet psychic”; Gera, who offered “angel readings, pet readings, mediumship”; and Dee, listed simply as a “medium-channel.” I paid $25 each for readings with Shelley and Gera. Dee, the channel, was a little more expensive, at $40 for a fifteen-minute reading. The cashier provided a ticket for each, with a sticker affixed to it listing the appointment time.

Ichabod the Spirit Guide and a Dog Named Fritz

Having experienced psychic readings before, I knew that the readers would ask me what topics I wanted to discuss. I decided to come armed with two. First, despite years of experience participating in paranormal excursions of various types, I have never had an unexplained experience. Do ghosts not like me? Have I shut myself off to UFOs and Bigfoot? I planned to go straight to the “source” and find out why the paranormal and I cannot get along.

For my second topic I decided to ask about the family dog. Three years previous, we had adopted a German shepherd from a local rescue organization. The dog did not have a name or a history. He had been found in a local wooded area without a collar and with burns on his legs and ears. The organization’s best guess was that he was about two years old at the time of the adoption. We named the dog “Bennett” and he instantly bonded with myself, my wife, and our two sons. Unfortunately, we are the only four people Bennett bonded with—should anyone else enter the home, he will sneak behind that person and bite him or her on the back of the leg. He also seems to intensely dislike both small dogs and cats. Two of my readers, Gera and Shelley, offered “animal communication” services. I decided to ask about our mysterious dog and its troublesome habits.

Shelley, a woman of about sixty with short, auburn-colored hair and a slightly nervous disposition, was my first appointment. I sat down and introduced myself. She turned a small egg timer to fifteen minutes and asked me what I wanted to talk about. I decided to start by talking about Bennett. She asked me what was my concern and I told her that he was biting people outside of his inner circle and had an unknown past. “Do you have a photo?” she asked next. I pulled out my phone and scrolled to a photo of Bennett. She held it in her hands for a few moments and then began making a series of observations.

It seems that Bennett previously belonged to a “man who drank” who did not provide him with a collar. The man did not abuse Bennett, but did frequently leave him in the yard alone. The dog eventually tired of this neglect and ran away from the man, which is why he was found in the park. Bennett is really grateful to our family, she said, and wants to make sure that we are protected, which is why he tries to drive others from the house.

Shelley had not intuited that Bennet had been in a fire, nor that he had a problem with small animals. I decided to ask her about those issues. “Ahh . . . ,” she said and thought for a moment. Bennett had been in a wildfire after he had escaped, which explains his burns. He does not like small dogs because a poodle used to live next door to him and “teased him mercilessly.” We might want to “use an animal specialist to try and get him some help,” she continued, and “make sure to have a long talk with him before any visitors enter the house to tell him that person is OK.”

Shelley appeared to bore of talking about Bennett and handed me a deck of tarot cards. I shuffled the deck and handed it back to her. There was a long pause, followed by a line of questioning about my family. She began to lay the cards out on the table, face up in rows of six. Shelley would turn over a card, ask a question and turn over another. Once she completed one row, she began another on top of the previous.

“So do you have two or three kids?”

“I have two.”

“Is the youngest one a girl?”

“No.”

“So he’s a boy then?”

“Yes.”

“And the older one?”

“He’s a boy.”

“OK. I see that the younger one is really into sports?”

“Not really.”

“Well he will have some interest in Little League next year.”

The egg timer sounded and I moved on to my second appointment.

Dee a short, thin, blonde woman in her sixties is a medium-channel whom I had noticed throughout the morning as she drifted into trances before her clients. Dee told me that she planned to channel an ascended master to discuss any issues I wanted to raise. I decided to ask Dee about my inability to have paranormal experiences. Is there anything the “other side” could tell me about why?

Dee smiled and informed me that she was going to start “channeling her guides.” “I am going to close my eyes,” she said, “and pretty soon it will no longer be me that is speaking.” The transition from “Dee” to whomever she claimed to channel was not abrupt or pronounced. Her eyes drifted shut, her mouth took on a slight grin, and she began speaking in a voice and cadence indistinguishable from her own. Once I figured out that I was speaking to the ascended master and had exchanged a few pleasantries, she began to discuss my paranormal “problem.”

“You do have a block,” she said, “but the reason is very, very farfetched. You are going to find this interesting. What is going on is that you have simultaneous lives going on. In your dream state you actually do a lot of your work. So when you are trying to do it here, it is too easy. Your brain sets up this block as a challenge. You want to challenge yourself.”45 Surprisingly, Dee/the ascended master immediately followed this revelation with: “But this could all be hogwash. Take it with a grain of salt. If it doesn’t resonate, find something else.”

Our time nearly up, Dee/the ascended master told me that I would, indeed, experience the paranormal some day (in my waking life). Soon I will become aware of my own personal spirit guide. He is a powerful wizard who will lead me on this journey, she finished.

For my final reading of the day with Gera, a pet psychic and angelic reader, I split my time between the two issues I had elected to raise with the psychics. We started by talking about the family dog, Bennett. I told her I had a dog with some problematic behaviors and an unknown past. She asked for Bennett’s name, the type of dog he is, and what he looks like. Armed with this information Gera closed her eyes and “tuned in” to Bennett.

“Oh . . . he’s already talking to me. He just said hi to me. German shepherds are so smart.”46

Gera giggled and exchanged a few pleasantries with Bennett. Finally, she asked what Bennett was doing that made us unhappy. I told her about his tendency to nip extended family members.

“Yeah. So . . . So . . . territory is important to him. Do you have any other dogs?”

“No.”

“No. All right. All right. He’s so grateful to your family for rescuing him that he feel like you are his pack. All right. So he’s protecting you. So now I need to tell him that its all right. . . . ‘Bennett . . . it’s all right to relax your protection for Chris’ family . . .’”

Eyes still closed, Gera giggled again.

“Oh . . . got it. . . . OK. . . . He says. ‘You’re not in charge. You need to be the alpha male.’ I’m tellin’ him that . . . that Chris is now in charge, that you’re the alpha male. He’s in charge of protection of the territory of the pack . . . of the family . . .”

A long pause.

“Oh my God. . . . You’re gonna laugh. He says, ‘Well if he’s in charge then he should mark.’ So if you can you go out in the yard and do that . . . at night . . . when nobody’s lookin’? Because he needs some boundaries and he needs to know that if you’re in charge you need to mark your scent. . . . OK, take this seriously. You’re the alpha male. He’s pretty literal about it.”

As Gera continued her psychic conversation with Bennett, she filled in his back story. Bennett is a very “staunch” and “serious” dog with a “totally German energy” who demands to be treated with respect. He lived with another family before ours but ran away when that family “would not take him seriously.” He feels respected by our family, Gera reported, except for his name:

“He just wants some staunch German name. Bennett is more English than German. He wants to be called . . . Fritz.”

In addition to a name change, she said, Bennett/Fritz also wants “more treats . . . lots more treats,” and a thicker cushion on his bed. Via Gera’s psychic gift, Bennett and I made a deal—he could have a thicker cushion, but must keep the name “Bennett.” Bennett agreed.

Nearly out of time at this point, I raised the other topic of the day—my inability to have paranormal experiences. Gera contacted one of her angelic guides and asked them this question. After a short pause and nod, she told me that a traumatic experience in a past life (or this one) has made me decide to shut down my “crown chakra.”47 I would need to learn how to open up the chakra to enable paranormal experiences.

“Your spirit guide can help you with this process,” she continued. “Let me ask the angels who your spirit guide is. . . . What do you do for a living?”

“I am a professor.”

“That’s funny! Your spirit guide is also a professor.”

“Really? Does he have a name?”

“Ichabod.”

Gera’s alarm rang, indicating our time was up. Learning more about Ichabod would have to wait.

American Belief in Psychic Powers

As I completed appointments with different readers, I could see the appeal of such phenomena. One could not help but impart some meaning to the possible futures and current insights produced by the readers. Earlier in the day, I sat in on a free, half-hour class on angelic reading provided by Gera. Shassa, a woman of about forty with a thick Russian accent, told Gera that she has always “felt like a stranger here,” and knows that she “has a home somewhere out there. Somewhere white.” Gera contacted the angels and told Shassa that she had lived on the planet Vega in a previous life and someday will return. Shassa left the room beaming. Another woman, Jill, told us that she had “always felt I had more to give the world than just being an administrative assistant.” Gera’s angels informed Jill that she has a spirit guide named Master Chen, who will soon guide her down a path to healing others. Tears rolled down Jill’s face. The need to learn something that would provide meaning or hope in one’s life was palpable in the room. Perhaps my need would have been more pronounced should I have come seeking guidance on more serious issues than an unfriendly dog and an inability to see ghosts.

While the appeal was obvious, skepticism was warranted. From two different readers I heard two different back stories for the family dog. Bennett was either kept by a solitary alcoholic that he ran away from due to neglect, or fled from a family that did not afford him proper respect. Shelley did not say anything about the fact that Bennett had been in a fire until asked. The topic never came up with Gera, and Bennett never mentioned anything about such a traumatic experience during their psychic conversation. According to Dee, I will soon discover a powerful wizard as my spirit guide who will lead me to paranormal experiences. Per Gera, however, Ichabod the professor is already waiting to guide me, should I open up my chakras.

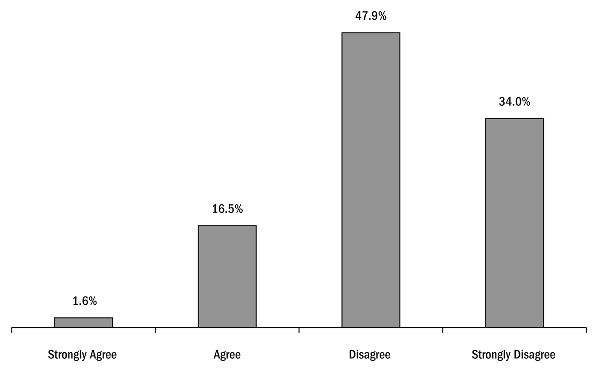

Americans express similar concern when asked about such topics. Fully 18% of Americans believe that astrologers, palm readers, fortune-tellers, and others who claim psychic abilities can see the future (see figure 2.3). But this also tells us that the majority of Americans (82%) remain skeptical about the ability to foresee the future (at least as far as these types of readers are concerned).

Figure 2.3. Astrologers, Palm Readers, Fortune-Tellers, and Psychics Can Foresee the Future (Chapman University Survey of American Fears 2014, n=1573)

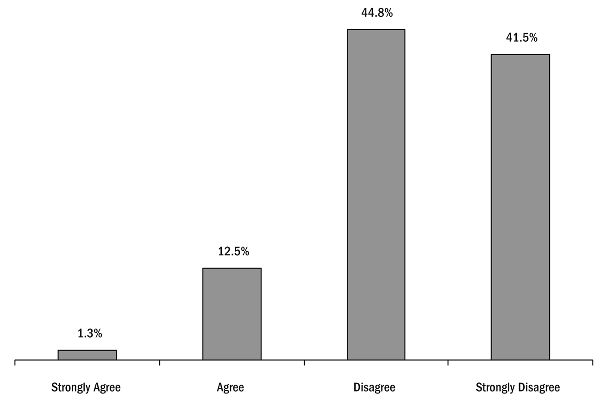

Figure 2.4. Astrology Impacts My Life and Personality (Chapman University Survey of American Fears 2014, n=1573)

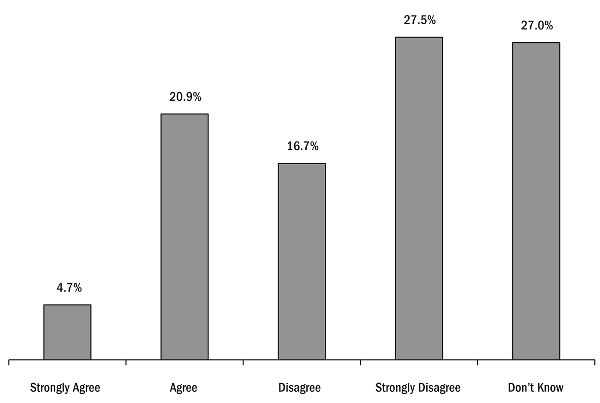

Figure 2.5. The Living and Dead Can Communicate with Each Other (Chapman University Survey of American Fears 2015, n=1541)

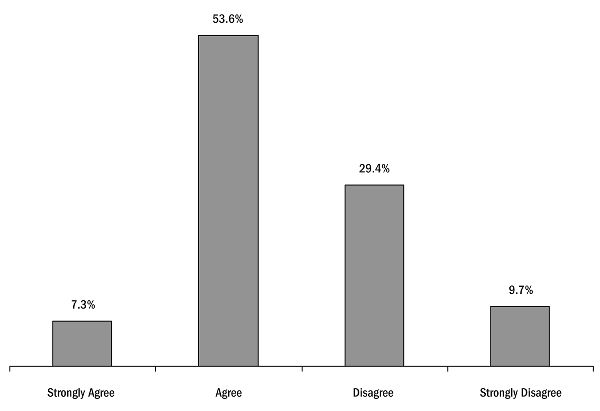

Figure 2.6. Dreams Sometimes Foretell the Future (Chapman University Survey of American Fears 2014, n=1573)

We find a similar pattern when we ask Americans more specifically about astrology (see figure 2.4). Americans are slightly more open to the idea of communication with the dead (see figure 2.5). On the other hand, most are convinced that dreams can foretell the future (see figure 2.6).

There are reasons for the mixed feelings Americans seem to have about the paranormal. To visit a psychic is to experience some “hits” surrounded by much incorrect information. Temple University mathematician John Allen Paulos recognized this phenomenon and labeled it the “Jeane Dixon effect.”48 When presented with a large amount of information, some true and some false, we are naturally more interested in the true statements. People tend to forget statements that are clearly false, leading them to overestimate the accuracy of psychics. Skeptics argue that psychics use the Jeane Dixon effect to their advantage. Readers pummel their clients with predictions, counting on the few hits to be recalled with reverence and the many misses to be forgotten. We can attest to this phenomenon. One cannot help to feel a slight thrill whenever an accurate statement is presented. The inaccurate statement immediately previous is much less interesting.

Skeptics have noted other processes at work in such readings. Readers often make vague statements that have a high probability of success, such as “I see that you have suffered a great loss in the last year.” One who has recently lost a parent to illness will connect with this statement, as will someone who recently had to put their beloved pet to sleep, suffered great losses in the stock market, or recently broke up with a boyfriend, and so on. Such vague statements are often coupled with observations that the client wants to be true. I certainly wish I was being followed by the ghost of a former professor. I want to believe that our dog Bennett is happy with our family, even if we refuse to rename him Fritz.

We could continue by discussing the possibility that many psychics are master “cold readers,” but to do so would be missing the point.49 Neither the readers nor the clients were at the fair in the hopes of proving the reality of paranormal phenomena to a skeptical public. People attend because they desire help and guidance and have not found the answers they seek through other means. Behind the use of crystal balls, palm reading, aura photography, attempts to contact dead relatives, psychics and clairvoyants, crystals, aromatherapy, past-life regression, handwriting analysis, and so on is the desire to better oneself. Clients hope to learn more about themselves by determining the color of their aura or gain supernatural insight into their future through the use of tarot cards or by communicating with dead relatives.

As the sociologist Jeremy Northcote notes, many paranormal believers “privilege experiential knowledge over empirical validity and the power of the imagination over the authority of physical reality.”50 That the methods being used at psychic fairs to elicit change or improvement remain unaccepted by science appeared of little concern to those involved. Personal enlightenment trumps scientific proof.

Enlightenment vs. Discovery

Wandering the Holistic Health & Spiritual Fair, I noted the absence of materials on several popular aspects of the paranormal. Bigfoot was in hiding, ghosts and UFOs largely absent.51 Judging by the prevalence of television shows, movies, books, and web pages devoted to such subjects, it might at first seem surprising that Sasquatch and aliens did not have a prominent place at such an event. Yet in our exploration of the paranormal, we have found that there are two distinct spheres within it, which we call—as described in chapter 1—enlightenment and discovery. These different approaches tend to align with different subjects.

For those that view the paranormal as a source of personal enlightenment, the “truth” is ephemeral and within: they seek to better themselves or learn about their fate by traveling in the realms of astrology, psychic powers, and similar practices. So long as psychic readings of one sort or another help them to come to grips with their strengths and weaknesses, they are satisfied. Since enlightenment pursuits highlight mystical experiences and magic, they share much in common with religion and rest closer to the boundary between it and the paranormal. The difference between the paranormal and religion is not ontological, at least from the perspective of science, for both psychic phenomena and religious phenomena share a focus upon the supernatural and are resistant to scientific confirmation. Further, religion and the paranormal are often not phenomenologically distinguishable either, as intensive religious and paranormal experiences can be very similar in their experiential features. The boundary is, rather, culturally defined, with organized religious groups deciding which types of mystical experiences are “authentically religious,” leaving those not included or demonized as “paranormal.” 52

Paranormal subcultures centered around enlightenment may attempt to transition into organized religions, but the road to cultural acceptance is treacherous and littered with the failed efforts of many a new religious movement. True to form though, the paranormal allows such efforts to avoid cultural death. As a result, the paranormal becomes a repository of supernaturalism that has not made the cultural “leap” into religion—a pool of ideas that new religions or other cultural movements may pull from (perhaps at their own peril).53 The paranormal can also become a repository for older religious ideas and traditions that have lost the benefit of conventionality, as is evident in the extensive borrowing from Eastern and esoteric traditions in New Age movements.

In contrast to enlightenment, others are interested in the paranormal because they hope to take part in, whether personally or by proxy, a major discovery for the world at large. People interested in Bigfoot and mysterious creatures in general, UFOs, and ghosts often appear more concerned with trying to prove to themselves and others that their subject is indeed “real.” They want to find the truth—a truth that anyone will accept. They want to find out if UFOs are real, or they know UFOs are real and want to convince others of that fact. Some of the most serious Bigfoot hunters hope to drop a Sasquatch carcass on the doorstep of the Smithsonian one day. They study materials on websites and in books, and debate the best evidence on blogs and at conferences. Others watch television shows such as Ghost Hunters with great interest, hoping the hosts will finally capture undisputed video of a restless spirit.

Consequently, discovery inhabits the borderlands between the paranormal and science, with professional scientists making distinctions between accepted knowledge and “amateur” or “pseudo” science.54 Meanwhile, the border between religion and science involved supernaturalism, but also the goal of the practices prescribed by each. Put another way, it is the ultimate goal toward which ascetic practices are directed that distinguishes religious asceticism (enactment of religious order) from scientific practice (systematic generation of knowledge about the physical world).55 Figure 2.7 outlines this cultural landscape of the paranormal in relation to religion and science.

The appeal of enlightenment is to learn about oneself, to maybe become a better person. The appeal of discovery is to share in an adventure, to feel the thrill of searching for the unknown, and perhaps to be the one who finally brings in the “proof.” Clearly, some subcultures blend aspects of enlightenment and discovery paranormalism, such as when UFO abductees emphasize spiritual themes or when ghost hunters utilize both mediumship and technological tools; but one need only to participate in each type of pursuit to feel their stark contrast.56