2

Research into and Theory of the Digital Divide

Introduction

In this chapter I will describe the characteristics of the research tradition concerning the digital divide over the last twenty years. There have been various approaches, so I will outline the general methodologies and theories, listing the most important research questions, themes, disciplines involved, strategies and methods, and, finally, the published results and their impact.

I will then go on to describe the theories formulated from four perspectives: the acceptance of technology perspective, the materialist perspective, the social-cultural perspective and the relational perspective. Deriving from these I propose a broad theoretical framework that can be used to explicate in the following chapters the results of research so far.

Research into the digital divide

Questions

At the turn of the twenty-first century the main question was who possessed a computer and an Internet connection and who did not. Researchers considered the primary demographics such as income, educational level, gender, ethnicity and employment status. The first institutions producing the statistics were national government departments and bureaus of official statistics, international bodies such as the United Nations, the World Bank and the European Commission (Eurostat), and telecom corporations with their branch organizations, such as the ITU. At the same time, scholars found the statistics produced by these bodies to be rather superficial. They wanted to know why particular people had computers and Internet connections and why others did not. To find answers their primary method was to conduct surveys, either on a large scale for whole countries or on a smaller scale for specific communities, such as students.

These scholars also asked what might be the development of access among populations in both rich and poor countries. Would everybody gain access to computers and the Internet as rapidly as had been the case with the television a generation before? Would there be only 5 or 10 per cent of the population in rich countries left without access, as for example with landline telephones, or would particular segments of the population lag behind permanently? Pippa Norris (2001) called the first projection normalization and the second stratification. To create these projections scholars used existing economic theories or those regarding social stratification and diffusion of innovation. One of the economic projections of normalization was the trickle-down principle, in which the adoption of new technologies always shifts from higher to lower social classes of income, education and occupation (Compaine 2001). Those who have the necessary resources first pay for the cost of a new technology, which makes adoption cheaper later on for those of lesser means.

However, others thought that the continuing stratification and cultural divisions among status, lifestyle and innovativeness were responsible for persisting inequalities of access. Finally there were the more technically oriented scholars who expected that digital media would become more and more easy to use, thus closing the access gap.

When physical access surged after 2000, another question arose: did those with access have sufficient skills to use digital media? In response, Eszter Hargittai (2002) announced the second-level digital divide, which focused on skills and usage. It was soon discovered that the skills needed were not only technical or operational but also information- or content-related. To investigate this, researchers began to use performance tests in laboratories and school classes. A subsequent question was whether people exhibiting inadequate digital skills were the same individuals as those with problems gaining physical access. Were differences of income, occupation, education, age, gender and ethnicity the same where both skills and access were concerned?

After 2005, questions about inequality of usage came to the fore. What was the frequency of use (time), the amount of use (number of applications) and the diversity of use (types of applications) among different social categories of users? Several Internet user typologies were created and a number of large-scale surveys were conducted to describe and analyse all these aspects.

Between 2012 and 2015 a growing number of researchers asked what were the benefits of having and using the Internet and what were the real disadvantages of not being online. Examples of benefits were cheaper products and services, the possibility of finding a job, maintaining and increasing social contacts, chancing on a partner, searching for information and help with health problems, examining political information, signing up for an educational course and following a cultural activity. The potential negative outcomes – excessive use, unwanted, unsafe and even criminal behaviour, and loss of privacy and the quality of face-to-face communication – were not examined. Researchers observed that the negative effects meant that some people didn’t use the Internet, but there was no particular focus on this (see table 2.1).

Table 2.1. The main research questions concerning the digital divide

| Issue | Question |

| Possession | Who has computers, the Internet and other digital media? |

| Motivation | Who wants computers, the Internet and other digital media? |

| Evolution | What is the growth in access to digital media in developed and developing countries? |

| Skills | Who shows sufficient digital skills? |

| Usage | What are the frequency of use, the amount of use and the diversity in use among all social categories of users? |

| Benefits and disadvantages | What are the benefits of being online and what are the disadvantages of not being online? |

Themes and disciplines

During the years of the first- and second-level digital divide, particular research themes became important. According to a systematic analysis of the literature between 1997 and 2012 by Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana (2015), the seven themes shown in table 2.2 were the most popular. Top of the list was access for consumers – to know who has access to digital media and networks and why; this was seen from both a supplier and a consumer perspective.

The second most popular theme was development, in the context of the level of development of a country and the innovativeness of its society. The enormous gap of physical access between developed and developing countries was a major topic of research, alongside the assumed boost given to development by gaining access to and the use of digital technology.

Table 2.2. The top seven research themes into the digital divide

Source: Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana (2015).

| Research theme | |

| 1 | Access for consumers |

| 2 | Development and innovativeness of countries |

| 3 | Education |

| 4 | Empowerment: community-building and participation in society |

| 5 | e-Health |

| 6 | e-Government and e-Participation |

| 7 | Capacities and applications of digital technology |

A third important theme was education, primarily the teaching of the necessary skills and competencies and the integration of ICTs in schools and universities.

In fourth place was empowerment, which could mean either the power of digital media for community-building and self-organization or the increase in active participation in several domains of society through digital media.

The fifth theme was e-health, particularly where the unequal use of health applications was concerned. It was assumed to be literally vital that people should have the skills to make use of such applications.

Issues of e-government and e-participation formed the sixth most popular topic. Inequality of access and the use of online public and social services, information about citizen benefits and the sources of information to participate politically were the points of investigation.

The last theme consisted of the capacities and applications of digital technology, which involved the differences in access, skills and usage entailed by particular versions of digital media. Often discussed were the differences between narrowband and broadband access, the opportunities of mobile technology for general use, and the evolution of the computer from mainframes and PCs to laptops, tablets and smartphones.

According to Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana’s summary (2015: 12), ‘the main areas of research are education, administration, development communication, telecom and IT, medical sciences, information science and economy.’ The question is whether these disciplines have investigated the digital divide.

The disciplines dominating the first-level digital divide were economics, primarily the consumer economy, together with telecoms and IT. The main researchers were the authors of the NTIA reports and the ITU reports, as well as individual authors such as Compaine (2001) and the marketing scholars Hoffman et al. (2000).

An early political scientist investigating the digital divide was Norris (2001). She was followed by education scientists such as Warschauer (2003), Solomon et al. (2003) and Selwyn et al. (2006); Warschauer also introduced the field into development studies by focusing on the digital divide in developing countries.

Sociologists and media and communication scholars showed an interest at the time the second-level divide was introduced. American scholars such as Servon (2002), Mossberger et al. (2003), DiMaggio et al. (2004) and Witte and Mannon (2010), Europeans such as Mansell (2002), van Dijk (2005), Zillien (2006), Livingstone and Helsper (2007) Robles and Molina (2007) and van Deursen (2010), and the South Korean Park (2002) combined sociology and media or communication science.

Currently, digital divide research is an interdisciplinary activity, with scholars scarcely making a distinction between economic, social, political, cultural, psychological, technical and information or communication science. Similarly, this book aims to be fully interdisciplinary in describing and explaining the digital divide.

Strategies and methods

Which strategies and methods of research have been used to ask all these questions? The most general strategy is making a choice between basic and applied research. Although the digital divide is clearly a societal problem, so far most research has been fairly basic, describing the current state of affairs. Only a small minority of projects investigate solutions applicable in practical settings. It seems that both scholars and policy-makers want first to understand the development of the digital divide before trying to find solutions.

The second characteristic of digital divide research is that it is more descriptive than explanatory. As I will argue in the rest of this chapter, it lacks a fully fledged theory. Much of it contains correlations between access, skills or use and personal demographics of age, gender and ethnicity or socio-economic factors such as income, occupation and education (Scheerder et al. 2017; van Laar et al. 2017). The deeper social, economic, cultural and psychological causes of the correlations are seldom addressed.

Digital divide research also is overwhelmingly quantitative. Most of it is based on data collected from large-scale surveys and attempts to capture the wider picture. Although this produces vast amounts of information, it does not come up with the precise mechanisms explaining the adoption and use of the technology concerned in everyday life. Qualitative ethnographic or field research is relatively sparse; examples are by Stanley (2003), Wyatt et al. (2005), Katz (2006), Ito et al. (2009), Clark (2009), Loos (2012) and Correa (2014). The dominant demographic and socio-economic variables in survey research lead more to socio-economic than to socio-cultural or psychological determinants of Internet use (van Dijk 2006; Scheerder et al. 2017).

By far the most frequently used strategy in digital divide research is the survey and the resulting official statistics, which are used for all phases: motivation, physical access, skills, usage and outcomes. Nationwide representative surveys, the predominant type, are most often in the form of self-administered questionnaires. Experiments are a second common strategy, mostly used for registering usage patterns and outcomes in particular situations in the field; they can also, for example, provide different connections, devices and support for comparison. The third strategy is performance tests administered by educational institutions or by scholars investigating digital skills. These are mainly used to observe skills or levels of literacy, although surveys are employed most for this purpose. The least frequently used strategy is ethnography or research observing actual, daily use in restricted fields.

So, the methods of data collection in digital divide research are primarily questionnaires that lead to scientific reports or official public statistics. Direct observation of behaviour is seldom practised except for in performance tests. Longitudinal research is scarce so it is difficult to show trends such as the evolution of phases of the digital divide. International comparisons made by international institutions such as the UN, the ITU, the World Bank, the EU and the World Internet Project, combining reports of universities in more than thirty-five countries (www.worldinternetproject.com), are more frequent.

Data analysis comes mainly from descriptive data. For major data sets, correlations or at best regressions are most popular. Causal modelling of big data sets is not frequent because of the lack of a comprehensive digital divide theory (see the second part of this chapter). Comparisons mostly involve only two models with a combination of a few variables.

Publications and their impact

Wang et al. (2011) mapped the ‘intellectual structure’ of the digital divide research community between 2000 and 2009 with a bibliographical and social-network analysis of 852 scientific journal papers and their 26,966 citations. They concluded that ‘the digital divide has gained the reputation as a legitimate academic field, with digital divide specific journals gaining the status required for an independent research field’ (2011: 54). A broader bibliographical and network analysis, including books, theses, conference and working papers and policy documents from 1997 through 2015, found 102,000 key terms in the text and 5,970 in the titles of English-language publications (Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana, 2015). Spanish publications showed 13,400 key terms in the text and 672 in the titles and Portuguese publications 486 in the text and four in the titles. Other languages were not covered.

This brings us to an important observation. More than half of the scientific publications and their citations of research into the digital divide come from the US, followed by the UK and other European countries. In the Spanish-language sphere, Spain, Mexico and Chile have most publications and citations, while in Portuguese it is Brazil (Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana, 2015). Other languages and countries are not covered, but they comprise a small minority in the scholarly domain. This means that the majority of research originates in English-speaking developed and (relatively) rich countries. Policy-oriented publications issued by (inter)national institutions (the ITU, the UN, the World Bank and others) focus on both developed and developing countries.

Another striking observation is that there is a divide between the academic publication domain and the policy-oriented domain of (inter) national institutions and official public statistics. The academics tend to cite each other, as do the policy researchers, meaning that the policy impact of academic research is possibly less than that of policy research and official statistics about computer and Internet access or use. This issue will be discussed in the final chapter.

Digital divide research is publicized much more in journal articles, conference and working papers and reports than in books. Nevertheless, books receive relatively higher rates when it comes to citations (Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana 2015: 7). Most articles are publicized by the English journals First Monday (open access), New Media & Society, Information Society, Information, Communication & Society, Telematics and Informatics and Telecommunication Policy. The most important authorities in the first decade of the twenty-first century were Pippa Norris, Mark Warschauer, Eszter Hargittai, Jan van Dijk and Donna Hoffman (see Berrío Zapata and Sant’Ana 2015: 8, 10).

Theories concerning the digital divide

The current status of theories

It was claimed above that digital divide research is predominately descriptive and that it has not yet produced a fully-fledged theory. However, many people have attempted to provide a theory, some of whom are developing fresh ideas and others are adopting or adapting existing theories. A fully-fledged theory requires at least four elements (see table 2.3).

Current and past research has produced many empirical statements and operational definitions of concepts used for mostly descriptive and correlational research. However, coherent theoretical statements or axioms and causal analysis are frequently lacking. Even when causal analysis is used, for example with structural-equational modelling, the model is not a reflection or a test of a basic theory explaining phenomena related to the digital divide. Most often they are merely an assembly of factors or variables which are statistically related and seem to follow a logical causal path.

Table 2.3. The four elements of a scientific theory and their characteristics

| Element | Characteristic |

| Theoretical statements | A coherent number of statements or axioms containing basic concepts and their relationships, perhaps to be portrayed in a model, which provide the so-called hard core of a theory |

| Basic concepts and operational definitions | Concepts with definitions for empirical research |

| Empirical statements | Statements that have been tested and supported in empirical investigations |

| Heuristics or preferred method | A method of research appropriate to the statements |

We are looking for systematic theories containing both theoretical and empirical statements and heuristics or empirical methods to test them in the future. Presently we have only a number of perspectives of developing or adopting theories. I will now discuss four perspectives.

The acceptance of technology perspective

Currently, a series of so-called acceptance of technology principles is available for a theory which might explain many aspects of the digital divide. Most theories of technology acceptance are psychological, drawing on behaviour, attitudes, motives, expectancies and intentions. Behavioural intention is the most important factor in such psychological theories.

The oldest theory in this domain is the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991; Ajzen and Fishbein 2005). This is a rationalist theory describing the ways in which people consciously choose or reject a particular technology. The initial causes are threefold, relating to behavioural, normative and control beliefs. Some people have a positive attitude towards computers, mobile phones and the Internet and others have negative attitudes towards them. In the following chapter I will show that these attitudes are very important in adopting or rejecting digital media. Normative beliefs here are stimulated (or not) by people’s social environment to become part of the digital world. Clearly this holds for the present young generation – ‘the digital natives’ – who have grown up with digital media. Finally, the perceptions of people that they are able to apply digital media, for example by means of skills, are the control beliefs. These three beliefs come into play before people accept a technology. So behavioural intention is treated here as a dependent variable.

A second theory frequently used to explain the intention to use a new technology is called the technology acceptance model (Davis 1989). In this theory the perceived usefulness and ease of use are what initially determine the attitude towards a new technology. These are in fact the attributes of a particular technology as perceived by potential users. In the history of digital media they have become ever more important in closing the digital divide. Generally, in the last twenty-five years both the usefulness and the ease of use of computer and Internet applications have dramatically increased. However, these measures remain different for different parts of the population.

The third psychological theory of technology acceptance is the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (Venkatesh et al. 2003). This theory claims to combine all statistically significant factors of technology acceptance for individuals in the context of organizations. Here the expectancies of the effort needed and the performance of the technology concerned, together with the influence people perceive from their social environment, are decisive for the intention to use it.

Probably the most popular technology acceptance theory in digital divide research is the diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers [1962] 2003). The psychological backbone of this broad interdisciplinary theory is the process involved in the decision to adopt or reject a new technology. The focus and dependent variable here is not the behavioural intention to adopt, as in the former theories, but adoption itself. This entails both personal characteristics, such as innovativeness, and societal factors, such as social norms for change, and the decision process is informed by communication sources. People are persuaded by the perceived technical characteristics of the innovation concerned. Digital media might be accepted when it is seen that they have a relative advantage over other or older media, when they are compatible with familiar media, when they are not very complex to use, or when people are able to observe and experiment with them in their own environment.

These four theories focus only on the first phases of access to a new technology, while the following theories concentrate on the use of a technology (see figure 2.1). The first is the uses and gratifications theory (Rosengren et al. 1985). The core of this theory of media and communication science is the sequence of basic needs, motives and gratifications searched for and obtained in using particular media. Some researchers, for example, list various gratifications gained through using the Internet (Cho et al. 2003; Song et al. 2004; Stafford at al. 2004; LaRose and Eastin 2004). Users seeking these gratifications are motivated to gain access and develop the corresponding skills.

Figure 2.1. Acceptance of technology theories in their various phases of acceptance

The sociological and communication theory known as domestication theory (Silverstone and Hirsch 1992; Silverstone and Haddon 1996) focuses on the initial and continued use of media in everyday life. The ethnographic method used here is to observe how people (re)design available media to suit their own context and their own purposes.

The last acceptance theory here is social cognitive theory (Bandura 1991, 2001). This is a theory of social learning, as people observe the media use of others in order to inform their own learning. After a while their expectations of the results are raised and they develop habitual use (LaRose and Eastin 2004 combine this theory with the uses and gratifications theory).

The materialist perspective

The materialist perspective looks primarily at the economic means and the social opportunities people have to acquire digital media. Previously in this chapter we have seen that socio-economic demographics form the most important variable in digital divide research. Income, socio-economic status, occupation, job and level of education have here been framed in more abstract categories emerging from existing social and economic theories.

Consumer economic theory attempts to explain the digital divide of (mainly) physical access through market costs. When prices drop – for instance, as chips, batteries and screens become cheaper – consumers are more able to purchase the relevant hardware. When new digital media first emerged, purchases were made largely by people with substantial incomes, while those on low incomes waited for prices to go down. This mechanism is called the ‘trickle down principle’ (Compaine 2001; see chapter 1).

From the perspective of Marxian economics, however, the digital divide would still exist because people’s living conditions and access to digital media are determined by more than market costs. One of the most popular theories from the materialist perspective is the capital theory of Bourdieu (1986), whose types of capital have been a source of inspiration for digital divide researchers in constructing variables for surveys. Economic capital – money, property and other assets – is exemplified by questions about income and the possession of connections, devices, software and subscriptions. Social capital – social relationships and network connections – is identified by questions about social support in gaining access, learning skills and using digital media. Cultural capital is acquired in three forms: embodied (learning knowledge and language), objectified (obtaining cultural goods) and institutionalized (diplomas, credentials and professional qualifications). It is seen in digital divide surveys in questions about the educational level attained by respondents and the status acquired by using digital media.

However, in digital divide research the variables identifying these types of capital are usually used only descriptively by finding correlations between kinds of access and these variables. The background of Bourdieu’s theory of social stratification, distinction, status and power in society (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990) is rarely discussed.

The second theory in this materialist perspective is the structuration theory of Giddens (1984), which states that social structures are made by human action via their rules and resources. Social and cultural rules constrain actions and several kinds of resources make them possible. In digital divide research, a set of resources is assumed to be supporting access in all phases. The most important are material resources (income and property), mental resources (knowledge and social or technical skills), social resources (connections and relationships) and temporal resources (time to spend in any activity, including using digital media). Social and cultural rules point to the way in which people are supposed to employ digital media.

Similar to Bourdieu’s capital theory, Giddens’s structuration theory is mostly used by digital divide researchers to derive lists of resources and rules in order to correlate them with access.

The socio-cultural perspective

The socio-cultural perspective shows more interest in the meaning, signification and (re)construction of the use of and access to digital technology. The point of departure is that access to and the use of digital media are embedded in everyday life and the socio-cultural context. The domestication theory mentioned earlier also belongs to this perspective. Researchers writing from this perspective are active in sociology, anthropology and media studies.

One of the pioneers is the classical sociologist Max Weber ([1922] 1978). Some digital divide researchers have recently called attention to a Weberian approach (Ragnedda and Muschert 2013; Blank and Groselj 2014; Regnedda 2017). While Weber was also an economist, he did not think that inequality was determined only by economic factors; factors such as status and prestige were important too. His argument starts with (un)equal life chances, comparable to the materialist concepts of resources and capital. Through these chances people conduct their life (in this context, they use digital media in their own way in everyday life). In so doing they have a number of life choices. The result is a particular lifestyle – here in which digital media have more or less importance. These four aspects of life in the work of Weber are explained by Regnedda (2017: 70).

Lifestyles determined by a particular possession and use of digital media create prestige and status; people with the same lifestyle create status groups of which many people wish to be a part. For young people, mobile phones and wearable computers form an important lifestyle and status marker. Without these symbols they are likely to be excluded socially. However, it is not only age that leads to cultural distinctions in the digital divide. Cultural differences of gender, ethnicity, social class, jobs or professions, and knowledge of languages can lead to unequal access and use of digital media.

We have seen that socio-cultural factors have been neglected in earlier digital divide research. Nevertheless, this perspective is useful for all phases of access, not least in the phase of motivation and the cultural distinctions of digital media usage.

The relational perspective

The last perspective to be discussed is a particular methodological approach which might possibly lead to a new basic paradigm. Most digital divide research is undertaken on the basis of so-called methodological individualism (Wellman and Berkowitz 1988). It often deals with individuals and their characteristics – level of income and education, employment, age, sex, and ethnicity. This is the usual approach in survey research, which measures the properties and attitudes of individual respondents.

A different perspective is the relational or network approach (Wellman and Berkowitz 1988; Monge and Contractor 2003). Here the most important units of analysis are not individuals per se but the relationships between individuals. Inequality is not just a matter of individual attributes but also one of categorical distinctions between groups of people. This is the view of the American sociologist Charles Tilly: ‘The central argument runs like this: Large, significant inequalities in advantages among human beings correspond mainly to categorical differences such as black/white, male/female, citizen/foreigner, or Muslim/Jew rather than to individual differences in attributes, propensities, or performances’ (Tilly 1998: 7). Other important categorical distinctions are employers and (un)employed, management and executives, people with high and low levels of education, the elderly and the young, and parents and children, while at the macro-level we may observe the categorical inequality of developed and developing countries, sometimes referred to as the core and periphery. The first of these pairings is generally the dominant category as far as the possession and control of digital media is concerned; the exceptions are the last two mentioned above – the elderly and parents.

The dominant category is the first to adopt the new technology, thus gaining an advantage to increase power in its relationship vis-à-vis the subordinate category. The example of gender inequality is instructive:

Gender differences in the appropriation of technology start very early in life. Little boys are the first to pick up technical toys and devices, passing the little girls, most often their sisters and small female neighbours or friends. These girls leave the operation to the boys, perhaps at first because the girls are less secure in handling them. Here a long process of continual reinforcement starts in which the girls ‘never’ learn to operate the devices and the boys improve. This progresses into adulthood, where males are able to appropriate the great majority of technical and strategically important jobs and, in practice, keep females out of these jobs. (van Dijk 2005: 11–12)

Table 2.4. Theoretical perspectives on the digital divide

| Perspective | Focus or core |

| Acceptance of technology | Attitudes, motivations, expectancies, intentions, adoptions |

| Materialist | Capital and resources |

| Socio-cultural | Meanings, life chances, life choices and lifestyles |

| Relational | Relations and power |

An advantage of the relational perspective is that it reveals the concrete mechanisms of growing inequality as compared to the more superficial explanations found among individual attributes (e.g. that females are supposed to be less technical). The perspective is also useful in the context of the rise of the network society, where interactions become ever more important (van Dijk [1999] 2012). However, unfortunately the relational perspective is not yet much utilized in digital divide research.

A general framework for understanding the digital divide

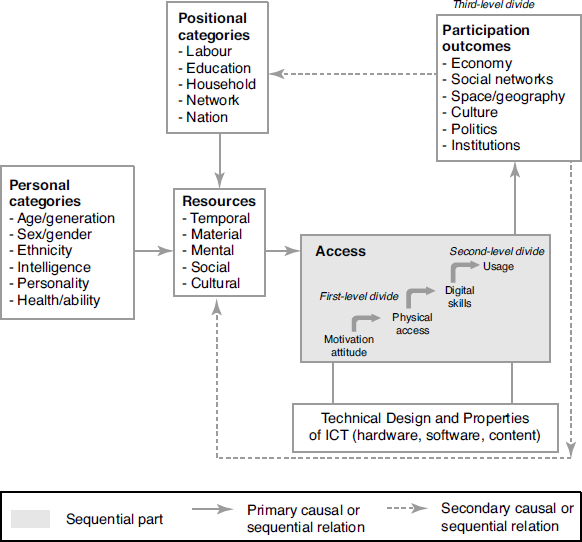

With these different perspectives (see table 2.4) it is not easy to find a neutral framework for understanding the digital divide. Any such framework will have to be derived from a very broad theory combining these four perspectives. With some hesitance I wish to propose my own theory for this task. It combines four of these perspectives, and it is open enough to allow for interpretation of almost every factor or variable of digital divide research (see figure 2.2).

The resources and appropriation theory (van Dijk 2005) is first of all a theory of technology acceptance, which it understands as a process – appropriation – rather than as a single intention or decision. This process is behavioural: first people have to be motivated, then they have to acquire or purchase the technology, and, finally, they have to learn to use it by developing the relevant skills. This process follows the first and second level of the history of digital divide research.

Figure 2.2. A causal model of resources and appropriation theory

This theory has its origins in the materialist perspective on account of the resources and personal and positional characteristics of individuals. In fact the theory conforms to structuration theory (Giddens 1984), since its core is a continual interplay of structures (rules and resources) and people’s actions or behaviours. Resources are not only material but also mental, social and cultural, so the socio-cultural perspective of meaning has a place in this theory too. Finally, the relational perspective is relevant because of the personal and positional characteristics of the categorical pairs.

The backbone of the theory is presented in figure 2.2. Personal and positional inequalities lead to different amounts of resources. These resources determine the process of technology appropriation in four phases of ICT access (motivation, physical access, skills and usage), and the outcomes of this process lead to more or less participation in society in several domains (economic, political, cultural, etc.). ICT access also depends on the technical characteristics of the digital media concerned.

The hard core of this theory can be summarized as follows.

- Categorical inequalities in society produce an unequal distribution of resources.

- An unequal distribution of resources causes unequal access to digital technologies.

- Unequal access to digital technologies also depends on the characteristics of these technologies.

- Unequal access to digital technologies brings about unequal outcomes of participation in society.

- Unequal participation in society reinforces categorical inequalities and unequal distribution of resources.

In this book the term ‘access’ in statements 2, 3 and 4 is a sequence of four phases: motivation/attitude, physical access, digital skills and usage. This is a linear logic in the model as a whole. In fact the model can also be applied in a circular manner. For example, motivation and attitude also influence skills and usage, and more usage often leads to more motivation.

The following personal categorical inequalities are often observed in digital divide research:

- age (young/old)

- gender (male/female)

- ethnicity (majority/minority)

- intelligence (high/low)

- personality (extrovert/introvert; self-confident/not self-confident)

- health (abled/disabled).

The same goes for the following positional categorical inequalities, which operate on both a personal and a societal level:

- labour position (entrepreneurs/workers; management/employees; employed/unemployed)

- education (high/low)

- household (family/individual)

- network (core/peripheral)

- nation/region (developed/developing; urban/rural).

In most empirical observations the first of these relational pairings have more access to digital technology than the second.

The following resources frequently figure in digital divide research, sometimes under other labels, such as economic, social and cultural capital:

- temporal (time to use digital media)

- material (income and property)

- mental (cognitive capacities and technical abilities)

- social (a social network to assist in acquiring and using digital media)

- cultural (lifestyle, status markers and habits in using digital media).

These factors are summarized in the full empirical model of this theory presented in figure 2.3. The theory was tested in several nationwide surveys in the Netherlands and the UK between 2010 and 2015 and, using the statistical method of sequential-equation modelling, was found to fit the data in causal path analysis (see van Deursen and van Dijk 2015b; van Deursen et al. 2017; van Deursen and van Dijk 2019).

This model will be used as a general framework and source of inspiration for understanding the results of digital divide research in the remainder of the book. However, the following five chapters will also review approaches and results of research other than those of the author.

Figure 2.3. A causal and sequential model of digital media access