4

Physical Access

Introduction: who possesses digital media?

At the time when research was taking place into the first-level digital divide (1995–2003), physical access was the main focus of scholars, policy-makers and public opinion. Today a common misconception is that the problem of the digital divide has been solved because almost everybody in the developed world is assumed to have some kind of computer, smartphone and Internet connection. In this book I argue that the problem only starts when everybody has a computer, smartphone or Internet connection! This is why my previous book was called The Deepening Divide (2005). Here I will show that this deepening divide tends to lead to more digital and social inequality, and I will make suggestions as to how to prevent this or at least to ameliorate it. This does not mean that the lack of physical access is no longer a problem. On the contrary, physical access is a prerequisite for reaching the next phases: developing digital skills, properly using computers or the Internet, and benefiting from them. In this chapter I show that the problem of physical access is here to stay, not only in the developing countries but also in the developed countries with very wide access. To demonstrate this, the concept of physical access has to be refined and specified.

In the following section the basic concepts concerning the types of physical access will be defined. A vast number of computer devices or applications and types of Internet connections have arrived in the last twenty years, which makes the problem of physical access more complicated. It is not only a quantitative problem but also a problem of quality: the nature and capacity of the technologies concerned.

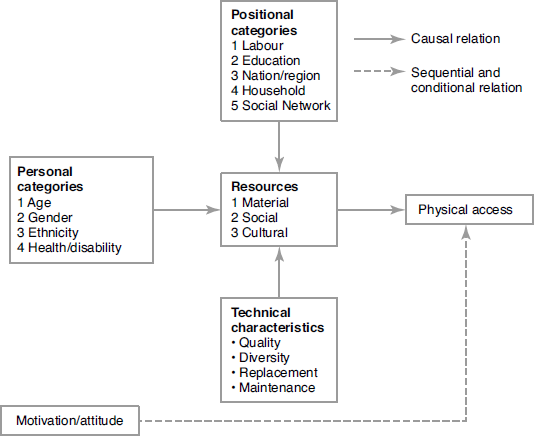

In the third section, we will look first at the causes of not having physical access. What are the resources shaping physical access? What are the positional categories such as work and education and the personal categories such as age and gender? A fourth set of background factors has to be added here, which consists of the technical designs and characteristics of the vast number of types of digital media now on offer. The price, the complexity, the user-friendliness and usability of all these types also affect physical access.

This will be followed by a discussion of the consequences of more or less physical access. What are the concerns of not having physical access? In which way will it affect the following phases of skills, usage and outcomes? What will be the diffusion of digital media in society as compared to traditional media and what will be the result? Will everybody acquire physical access to digital media in the future, or will part of the population be excluded permanently?

The last section deals with the evolution of the digital divide vis-à-vis physical access. What is the historical pattern observed? Did the division in physical access start with a growing gap among populations and countries? Did this gap close at all? What will be the future: will there perhaps be other gaps following the arrival of various new types of digital media?

Basic concepts

In this book, as in previous ones (van Dijk 2005; van Dijk and van Deursen 2014), I want to make a distinction between three concepts: physical access, material access and conditional access. My definition of physical access is the opportunity to use digital media by obtaining them privately in homes or publicly in collective settings (schools, libraries, community centres, Internet cafés and other places). The first option is private ownership and the second is collective use. In the history of diffusion of digital media in society, physical access was at first largely collective, and this remains the case in developing countries. Today, however, there has been a shift from collective to individual adoption in the use of mobile computing with smartphones. This is also the case in developing countries, where mobile phones are increasingly displacing the need to go to a centre such as an Internet café. Currently, the collective setting needed for mobile computing is to be within reach of some kind of Wifi. However, powerful or advanced computers and broadband connections are still needed for work and education in collective settings and for leisure applications requiring a high capacity in private settings.

The second concept, material access, is broader than physical access. It can be defined as all means needed to maintain the use of digital media over time, including subscriptions, peripheral equipment, electricity, software and print necessities (e.g. ink and paper). In an even broader definition, it also includes the expenses of elementary computer courses required to be able to use digital media, additional expenses which tend to increase over time as software changes and which may eventually exceed the cost of the devices and connections.

The third, more limited concept is conditional access. Devices and connections are often not enough to acquire a particular service. Every Internet user is familiar with the numerous user names and passwords needed to get access to websites. Conditional access can be defined as the provisory entry to particular applications, programs or contents of computers and networks. The conditions are payment or a particular position, membership or allowance that is required at the workplace or schools and for membership of organizations or activities. Payment and entitlements are becoming increasingly important in the commercial and insecure World Wide Web.

All three types of access defined here are becoming more and more complicated when we look at the expansion of the types of devices and applications and network connections available today. Digital divide researchers and (non-)governmental organizations still focus on simple individual and country figures revealing the number of computer, mobile phone and Internet users per population. More researchers now break down such figures to include the type of computer (PC, laptop, tablet, etc.) and mobile phone (smartphone or feature phone), as well as whether narrowband or broadband connections are used, but there are few statistics of this kind and even fewer concerning the newest digital media and their capacities – equipment linked to the Internet of Things, devices of augmented reality such as smart glasses, virtual reality headsets and wearables (watches and activity trackers). The focus of research needs to shift from measuring separate digital media to taking into account the processing and communicating capacities of the total information system or networks linking separate devices. This means having an eye for the quality and capacity of all digital media connected in a system.

Hilbert et al. (2010) and Hilbert (2016) criticised the simple and stand-alone traditional approach and instead measured the amounts of information processed and transmitted by digital media and networks. These measurements are of the information-processing capacity of countries and individual installations, with the value of bits that each piece of equipment can store, the amount of kilobits per second (Kbps) it can communicate and the amount of MCps (million computations per second) it can compute (Hilbert et al. 2010: 168, table 2). This might appear to be a rather technical approach. Still, most users know that a broadband connection is much faster than a narrowband connection, that a smartphone gives a much better performance than a feature phone, and that a desktop or laptop computer can accomplish more than a tablet.

In this chapter I will try to take into account both this diversity and the technical quality and capacity of digital media.

Causes of divides in physical access

Resources and physical access

The immediate differences observed in physical, material and conditional access are due to people’s resources. Evidently, material resources are by far the most important. Almost all research shows that income is most relevant for gaining access to digital media. Although basic digital media have become cheaper in the last thirty years, many people around the world, including those of modest means in rich countries, still cannot afford them.

Clearly, income is strongly related to employment or occupation and the level of education attained. Surveys often show that it has an independent effect (Zhang 2013; Bauer 2017). The wealthy have a good number of the best computer devices and phones, broadband Internet at home and mobile access via smartphones, and expensive and extended subscriptions. Those of modest means may own only one type of computer and one phone, lack home broadband, and perhaps have only a cheap feature phone and a basic subscription.

The second important resources are social. People enjoying many social relationships benefit from support, perhaps in acquiring a second-hand or borrowed computer, together with all kinds of software, peripherals and appliances and the use of an Internet connection at the home of others. Such relationships are vital in getting access to the world of digital media, especially in developing countries. Unfortunately, many poor people have fewer social relationships than rich people, and their social isolation can amplify digital exclusion.

In this book I often claim that social and cultural causes are just as relevant to the digital divide as economic causes. Cultural resources are ideas and values solidified or materialized in habitual behavioural patterns, cultural distinctions and artefacts. The most important of these are observable status markers, lifestyles, and how people react to the social world around them. Flashy new media devices are status markers for many, and some tech-savvies immediately want to attain distinction by having the latest gadget. They part with large amounts of money to purchase such items. Others may have lifestyles marked by spending all day using several kinds of digital media. This applies particularly to those living in the colder countries of the northern hemisphere, who pass more time indoors, while those in the sunnier southern countries are accustomed to living a more outdoors life. Finally, those involved in using digital media all day for entertainment purposes require more hardware, software and high-quality Internet access than those who use digital media occasionally for information and communication tasks (Robinson 2009).

Compared to material, social and cultural resources, temporal and mental resources are less important for physical access. People who do not have the time to use digital media might still possess them, and mental resources, while crucial for motivation, have no direct influence on physical access. A notable exception, though, are individuals with serious mental and physical handicaps, who actually seldom purchase digital media.

Positional categories and physical access

Work and education are the principal factors driving the distribution of material, social and cultural resources. In the 1990s, those with office jobs and in management positions were the first to obtain computers, though, while academics, teachers and technicians actually used them themselves, managers and directors tended to delegate computer work to their secretaries. At that point manual and unskilled workers were unlikely to have access to computers, while using both computers and the Internet became a necessity in administrative and commercial jobs in most middle-class occupations.

Today, it remains the case that, in almost every national survey undertaken in the developed countries, people in such occupations have more access to computers and the Internet than manual and unskilled workers. Although the gap has closed since the 1990s, those employed in middle-class jobs tend to have 100 per cent access while those in the lower occupations have approximately 70 to 80 per cent access. For example, Arabs in the state of Israel, who generally have lower incomes and less education, hold primarily manual and unskilled jobs and so have less access (Mesch and Talmud 2011). In the developing countries overall, the gap between the employed and the unemployed and between the well-educated and those of low education is still very pronounced (World Bank 2016; ITU 2017).

The second positional category is education, which is closely related to the category of labour but also has an independent effect. Individuals in education simply need a computer and Internet connection, at least in developing countries. In the 1990s the gap in use between those with high and low education was very wide, though it began to close about 2005. For example, in the US in 2000, the gap in physical access between people with at least a college degree and those with high school education or less was 59 percentage points (Perrin and Duggan 2015). In 2015, 95 per cent of people with college education or a graduate degree said they were Internet users, while the figure for those who had not completed high school was 66 per cent.

In the developing countries the gap is still growing today (World Bank 2016; ITU 2017), with the uneducated lagging considerably behind those who have completed schooling. In the future the gap will close here too, but most likely it will persist to a larger extent than in the developed countries.

The third positional category determining physical access is being an inhabitant of a particular nation, together with living in an urban versus a rural or a rich versus a poor region. Despite the fact that some individuals may have plenty of personal resources, they also depend on the economic and technological infrastructure and wealth of their country or region. There are differences in the reliability of the electricity supply, technological support after frequent breakdowns, the availability and reach of public access points, the economic support of governments and businesses with their subsidies or prices, and the educational support of schools.

The divides between developing and developed countries have always been wide, and in the 1990s and between 2000 and 2010 they were only becoming wider (see figure 4.1). Since 2010, Internet access has been growing at the same speed in all countries, so that after 2020 the gap will become narrower. A saturation phase is approaching in many developed countries, and the proportion of those online in the developing countries is nearing 50 per cent.

Figure 4.1. Internet users per 100 inhabitants in the developed and developing world

However, access in the developing countries is not growing at the same speed in middle-income and low-income countries. In the middle-income countries, among whom are the new emerging markets in East Asia, South Asia and South America, access is growing fast, while the poorest countries are lagging behind, with figures of less than 10 per cent (Zhang 2013: 522; Hilbert 2016; ITU 2017: 13).

In every country, urban regions have much more physical access than rural regions. Remote places often have less reach and broadband capacity. The countryside offers less work and fewer schools requiring information and communication technology than cities, with their schools of higher education, government departments, and financial and industrial concerns. Poor inner-city districts, however, have less access than affluent suburban neighbourhoods.

The fourth positional category is living in a particular household. On average, single-person households have less access to computers and the Internet than multiple-person households, especially families with school-age children. These benefit from a single connection and are able to share computers, other devices and subscriptions.

The last positional category is having a particular position in a social network. Networking allows new ideas and practices to spread (Valente 1996), and a central role in a large network enables individuals to find and share the best hardware, software and applications. People who are socially isolated offline and gain only a marginal place in a social network online find less support and fewer opportunities (Tilly 1998).

Personal categories and physical access

The most frequent personal categories affecting physical access observed in research are age, gender and ethnicity/race. Rarely noted is the category of (dis)ability. Intelligence and personality have influence on motivation and attitude but no direct effect on physical access.

By far the most important personal category is age. In all countries young people have more and earlier access to computers, mobile phones and Internet connections than older people. This is both a generational and a structural effect. Generational effects are the strongest, since individuals over the age of forty did not learn to use the digital media in their youth and have to learn to use them at work or by themselves at home. Those born after 1980 (the Millennium generation) have grown up with and been educated with digital media. As this generation ages, a shift will take place: middleaged people and the youngest generation will tend to have equal access to and use of digital media.

However, at the same time structural effects are at work. Digital media have become so vital for society that the elderly are catching up. In the developed countries a majority of people over sixty-five now have computers, smartphones and Internet connections and also use social media and other Internet applications.

A negative structural effect in terms of equal access among older people is also evident. Young people are naturally more innovative and want to experiment with digital media, while seniors are more attached to traditional media. Another structural effect is that young people are required to follow modern educational systems, while older people have to learn to use digital media via adult education computer classes. Structural effects tend to remain, while generational effects will disappear after a couple of generations.

The balance of the generational and structural effects today is that the gap in physical access between the young and the old continues to be pronounced. It is not as wide as it was twenty years ago, but in both developed and developing countries it is still noticeable. For example, in the US in 2015, only 58 per cent of people aged over sixty-five had Internet access, while people between eighteen and twenty-nine had 98 per cent access and those between thirty and forty-nine had 93 per cent. Worldwide, the young between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four had 71 per cent Internet access in 2017, while those older than twenty-five had only 48 per cent. However, in the developing countries the distribution was larger (67.3 versus 40.3 per cent) than that in the developed world (94.3 versus 81.0 per cent; see ITU 2017).

The second important category is gender. In terms of physical access, the gender gap between women and men is much smaller than the age gap. In 2017, it was 11.6 per cent worldwide (ITU 2017). In developing countries, people have less access at home, and many women, if employed, are only in manual or unskilled jobs. The result is that the gender gap in the developing countries is much wider than that in the developed world. In 2017 it was 16.1 per cent on average (25.3 per cent in Africa) as compared to the average of 2.6 per cent in the developed world. The Americas even reveal more access for females than males – +2.6 per cent! (see ITU 2017: 19).

The third important personal category is ethnicity, though in the domain of the digital divide this category pertains mostly to economic and educational disadvantage, social isolation, or spatially concentrated poverty and cultural preferences. The only independent effect of ethnicity consists of particular cultural preferences in wanting or using particular digital media.

In multi-ethnic countries such as the United States and Brazil, gaps in Internet access between the ethnicities are significant but not as wide as we have seen with age. In the US, English-speaking Asian Americans had the highest figure of access in 2015, at 97 per cent, while white Americans had 85 per cent, Hispanics 81 per cent and African Americans 78 per cent (Perrin and Duggan 2015). In Brazil, whites had significantly more Internet access than non-whites between 2005 and 2013, while access to a mobile phone was not significant; divides in age, income and education were more important (Nishijima et al. 2017).

The last personal category affecting physical access is (dis)ability. Although the disabled could find many advantages from Internet use, especially those with mobility problems, they in fact have less physical access to and use of digital media. In all parts of the world this gap is significant (Fox 2011; Ofcom 2015; Duplaga 2017). Here again, disadvantages of low income, less education and unemployment are responsible, but there is an independent effect of disability too. In this case, the design of hardware and the web is to blame. Many devices are not adapted for people with physical handicaps, and official web guidelines for the blind and deaf are often ignored.

Technical characteristics

While digital divide research has primarily used simple and basic indicators of physical access, such as the percentage of computer and mobile phone possession and Internet access, after the year 2000 these indicators became less and less adequate to determine the distinction between inclusion in and exclusion from the digital world. Digital technology is changing very fast, and at least four characteristics require differentiation.

The first is the technical capacity of devices, software and connections. The range of power in the various devices is enormous, software is available in basic and extended versions, and Internet connection speed ranges from very limited narrowband through to super high-speed broadband. The quality of digital technology defines its potential use. Martin Hilbert (2016) argues that the gap in Internet access between the developed and developing countries is in fact much wider when compared with basic access, and that the digital divide in physical access is here to stay. He measured the installed bandwidth potential of 172 countries between 1986 and 2014 and found that the inequality between developed and developing countries is extremely high and concentrated in Asia (including Russia), with more than 50 per cent.

The second characteristic is diversity. Digital media have multiplied since 2000, and we now have a growing number of types of computer, from mainframes and PCs through laptops and tablets to smartphones with big or small screens. Software is available from very advanced versions to very simple apps. Internet connections are focusing on the web, fixed and mobile phones, television and radio, and the Internet of Things. The crucial fact here is that some people have all of these devices, together with their software, while others have at best only one, meaning that the inequality of technical potential is growing (van Deursen and van Dijk 2019).

Along with this growing diversity we see that replacement of basic devices and connections is taking place. The most striking trend is the transition to mobile devices and connections. The developing world went mobile from the start because fixed connections were too expensive. In the developed countries today, a shift is occurring from home broadband to smart mobile phones (Perrin and Duggan 2015). Similarly, people are exchanging PCs for laptops, tablets and smartphones. However, the importance for the digital divide is that these replacements do not necessarily have the same use potential. Feature mobile phones, laptops, tablets and even smartphones have less advanced applications and contextual convenience and offer less enjoyment to the user than powerful PCs with their big screens and broadband connections. The main advantages are in their mobility and price.

A fourth technical characteristic of digital media is that they are unstable, regularly break down, often have to be repaired, and continually require updates. This is the problem of technology maintenance (Graham and Thrift 2007; Gonzales 2014, 2016). In developing countries there are frequent electricity blackouts and often a lack of transport for people to reach places such as Internet cafés; it can be difficult and expensive to repair broken mobile phones and old PCs. Figure 4.2 shows the causal argument so far (the order of factors in the boxes, apart from that for technical characteristics, is estimated).

The consequences of divides in physical access

Divides in physical access are a necessary condition of all the subsequent phases arising from the adoption of digital media: skills, usage and outcomes. The early assumption was that, once everybody had access to a computer and the Internet, the digital divide would be over.

Figure 4.2. Causal and sequential model of divides in physical access

Physical, material and conditional access leads to the opportunity to learn digital skills. However, the quality of the hardware, software and connection available, and the time they are accessible to a user if they are sharing them in the context of public access, also affect the opportunity of obtaining digital skills.

Physical, material and conditional access affects usage too. Quality and time determine the type and frequency of digital media use. A broadband Internet connection that is constantly live stimulates much more daily use and high-quality application than a narrow-band dial-up connection. An advanced high-capacity PC offers more usage opportunities than a tablet. A smartphone makes a world of difference compared to a simple feature phone.

Finally, the outcomes of unequal use of disposable hardware, software and connections can be quite different. Someone who possesses high-quality examples of all available technical resources will benefit more than someone who has only one inferior device, a slow connection and a basic Internet subscription.

The evolution in divides of physical access

While the common perception, based on theories of market economics and the diffusion of innovations, is that the physical access divide will eventually close, I call this into question.

The principal market economic theory is the trickle-down mechanism, whereby status products that are first adopted by the rich or the elite later become affordable for the less well-off. The mechanism was first applied to the digital divide by Thierer (2000) and Compaine (2001), who stated that the digital divide was a myth and that it would soon disappear. The market would solve the problem once cheaper and simple computer products appeared. It was just that people with lower incomes would only gain access later, as was the case with previous media innovations – the telephone, the radio, the television and the video recorder.

Computer products and connections are indeed much cheaper than before and in the developed countries are now within reach of even relatively poor people. However, the digital divide of physical access has not disappeared because the technology constantly requires more, and more complex, investment than did radio, television and the telephone.

Diffusion of innovations theory, based on sociology, communication science, marketing and development theory (Rogers [1962] 2003), describes with the aid of the so-called S-curve the evolution of physical access or adoption of new media by various groups: the innovators (2.5 per cent), the early adopters (13.5 per cent), the early majority (34 per cent), the late majority (34 per cent) and the laggards (16 per cent). This model might be attractive for marketing scholars, but I have many problems with it (see van Dijk 2005: 62–5), as it is too deterministic (why should every medium reach 100 per cent of the population?) and normative (think only in terms of the names of the adoption groups: the first are good and the last are bad).

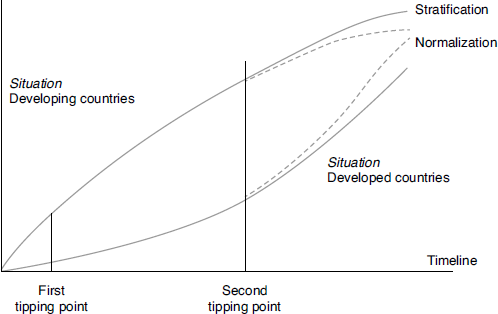

To ‘save’ the model of the S-curve, several qualifications are required. One is to define different groups of adopters. Pippa Norris (2001) distinguished two patterns in terms of the S-curve: normalization and stratification. In the normalization pattern, groups are only earlier or later in starting on the curve and faster or slower in following it; eventually all of them will reach the same goal of universal access. In the stratification pattern, groups from particular social strata (in terms of status, income and power) follow a different path on the curve. These groups have different resources at the start, so that the higher strata reach their peak earlier than the lower strata, who may never reach universal access (Norris 2001; van Dijk 2005).

Figure 4.3. The evolution of the digital divide of physical access over time

These two patterns also occur at the level of countries. Figure 4.3 shows that countries in the first stages of physical access exhibit widening gaps between people with high or low income, education and age combined. These gaps begin to close after a second tipping point, when about 50 per cent of the population gain access. In the figure, the lower line represents older people with low education and low income and the upper line younger people with higher education and a high income. The average physical access of individual countries can be mapped at a particular time and place. For example, in 2018 developing countries such as Eritrea, Chad and Burundi would be at the bottom left of the figure, while South Korea and Northern European countries would be at the top right.

A summary of statistics about computer and Internet access shows that, between 1984 and 2002, the gaps in income, education, employment, ethnicity and age were indeed widening in the developed countries (van Dijk 2005: 51–2). Between 2003 and 2006 these gaps started to close in these countries (see regular surveys by, among others, the Pew Research Center and NTIA in the US and the Oxford Internet Institute in the UK). However, in 2018 these gaps are still widening inside the developing countries (see annual reports by the ITU and the UN’s World Development Reports).

Two major conclusions can be arrived at in the shape of expectations:

- Near universal access to a basic computer and Internet connection should be available to the vast majority of the population in developed countries within one or two decades. However, if the stratification pattern holds, ‘near’ universal access might mean that 10 per cent or more of the population still have no access. In the developing countries, on the other hand, near universal access might take two or three decades, and in the meantime a stratification pattern will account for perhaps a quarter or third of the population being excluded.

- However, the digital divide of physical access is here to stay in another guise. Increasingly, having basic hardware and a slow connection is not enough for an individual to be included in the digital world. General material access and specific conditional access will become more important. This does not mean that hardware is no longer a problem. On the contrary, its quality or capacity, its diversity and continuous replacement and maintenance will create new physical access divides.

The final conclusion is that closing the gaps in physical access will not put an end to the digital divide: there will remain inequality in skills and usage, which I will now discuss.