CHAPTER 1: FROM DEMON POSSESSION TO THE 15-MINUTE MED CHECK: A BRIEF HISTORY OF MENTAL ILLNESS DIAGNOSES AND TREATMENTS

The first known use of “headshrinker” as a slang term for a psychotherapist appeared in the Nov. 27, 1950 issue of Time magazine, which asserted that anyone who had predicted the phenomenal success of the television Western Hopalong Cassidy would have been sent to a “headshrinker.” The article explained in a footnote that headshrinker is Hollywood slang for a psychiatrist. . . . The headshrinker metaphor arguably reflects the feelings of fear, mystery, and hostility traditionally associated with the profession. Another theory holds that it implicitly refers to shrinking a patient’s narcissistic, inflated sense of self. Although many mental-health professionals have come to accept the term with self-deprecating humor, it has also been criticized as a relic of an outmoded therapeutic approach that reduces people to mere causes and symptoms rather than regarding them as complex individuals.[22]

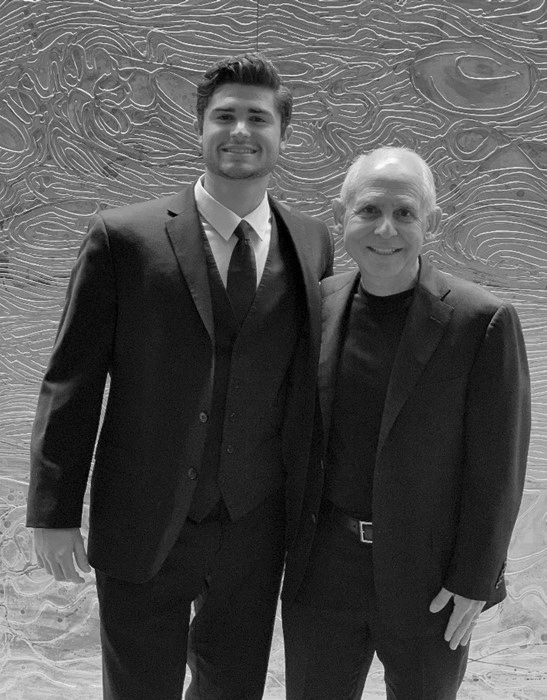

When one person gets better, it can cause a cascade of help across generations of people. When I first met my wife, Tana, in 2006, I really, really liked her. Having been divorced for six years, I had told myself that before I ever married again, I would need to see the woman’s brain scan before going to the next level. About three weeks after we met, I invited Tana to the clinic. She was a neurosurgical intensive care nurse, and we bonded over our love of the brain, so it wasn’t that weird. Her brain was beautiful, and two-and-a-half years later we were married. Over the years, that one scan changed many other brains.

A few months after Tana was scanned, a neurologist diagnosed Tana’s estranged father with Alzheimer’s disease, but when I scanned her dad, his SPECT scan showed he did not have Alzheimer’s disease but, rather, depression masquerading as it. We prescribed natural dietary supplements for him, and several months later, he was able to teach a six-hour seminar at a local church. Then Tana’s mother and uncle were fighting at work, so I evaluated and scanned them. It turned out they both had terrible attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). On medication they got along much better, and their business improved. Then, a friend of Tana’s from her early 20s saw us on a public television show together and reached out to Tana because her son, Jarrett, was really struggling.

JARRETT

Jarrett was diagnosed with ADHD in preschool. His mother said he was driven by a motor that was revved way too high. He was hyperactive, hyper-verbal, restless, and impulsive, and he couldn’t focus. He also didn’t sleep well and interrupted everyone all the time. He had no friends —his classmates avoided him, and their parents kept their children away from him. His third-grade teacher said he would never do well in school and cautioned his parents to lower their expectations. He had seen five doctors and was prescribed five stimulant medications for ADHD. All of them made Jarrett worse, triggering mood swings and terrible rages. He put holes in the walls of their home and scared his siblings. His behavior had gotten so bad that his last doctor wanted to put him on an antipsychotic medication. This is when his mother brought him to see us. Jarrett’s brain SPECT scan clearly showed dramatic overactivity in a pattern we call “the ring of fire.” No wonder stimulants didn’t work; it was like pouring gasoline on a fire. Our published research shows that stimulants make this pattern worse 80 percent of the time.[23]

On a group of natural supplements to calm his brain —together with parent training and structured, brain-healthy habits —Jarrett’s behavior dramatically improved. His grades went up, the rages stopped, and he was able to make friends. He has now been on the honor roll for eight straight years. After searching for so long, his parents are grateful to have found the correct treatment plan for him, which has completely altered the course of his life. There is no telling what the future would have held for Jarrett if he had stayed on his previous path.

Jarrett and Dr. Amen

JARRETT AND DR. AMEN

HOW WOULD JARRETT HAVE BEEN TREATED THROUGHOUT HISTORY?

The word psychiatry originates from the Medieval Latin psychiatria, meaning “healing of the soul.”[24] Many societies have viewed mental illness as a form of divine punishment or demon possession. This chapter will walk you through history to show you some of the strange and unsettling things that would have been prescribed in an attempt to heal Jarrett.

Ancient civilization

In ancient Indian, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman writings, mental illness was often seen as a religious or personal failure. As early as 6,500 BC, prehistoric skulls and cave art showed evidence of trepanation, a surgical procedure that involved drilling or scraping a hole in the skull to release evil spirits thought to be trapped inside.[25]

Treatment: Religious leaders may have attempted an exorcism for Jarrett or drilled a hole in his skull to release the evil spirits.

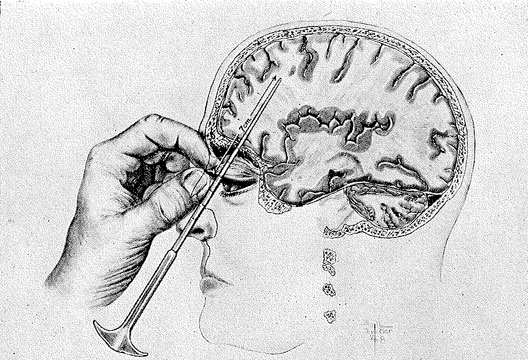

Trepanation to Allow Trapped Evil Spirits to Escape

TREPANATION TO ALLOW TRAPPED EVIL SPIRITS TO ESCAPE

HIPPOCRATES

The Greek physician Hippocrates (460–370 BC) believed all mental illnesses came from the brain.[26] He wrote, “Men ought to know that from the brain, and from the brain only, arise our pleasures, joy, laughter, and jests, as well as our sorrows, pains, despondency, and tears. . . . And by the same organ we become mad and delirious, where fears and terrors assail us. . . . All these things we endure from the brain, when it is not healthy.”[27]

Recognized as the “father of medicine,” Hippocrates proposed one of the first classifications of mental disorders, including mania, melancholy, phrenitis (brain inflammation, fever, delirium), insanity, disobedience, paranoia, panic, epilepsy, and hysteria. Some of those terms are still used today. The renowned physician did not view mental illness as shameful; he believed that mentally ill people were not responsible for their behavior and advocated that their family care for them at home. He was a pioneer in treating mentally ill people with more rational techniques, focusing on changing a person’s diet, environment, or occupation and adding medications, exercise, music, art therapy, and even divine solicitation.

It’s incredible to consider that nearly 2,500 years ago, Hippocrates was already suggesting that mental illnesses should be treated as physical medical illnesses and treated with lifestyle changes (the main point of this book).[28] However, he also theorized that physical and medical illnesses were caused by an imbalance of four essential bodily fluids or humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm), which is partly to blame for the practices of bloodletting and purging (similar to taking laxatives to empty the bowels).

Treatment: Likely, Hippocrates would have had Jarrett exercise, listen to music, create art, and focus on an occupation that fit his restless nature. He may have also bled him to release excess blood and had him take some natural supplements.

GALEN

Galen (AD 130–201), another Greek physician during the Roman Empire and ultimately one of the most influential physicians in history, agreed with Hippocrates’ four-humor theory of illness and associated them to four temperaments:

- Sanguine (blood: extroverted, social, risk-taking)

- Phlegmatic (phlegm: relaxed, peaceful, easy-going)

- Choleric (yellow bile: take-charge, decisive, goal-oriented)

- Melancholic (black bile: creative, kind, and introverted)

Like Hippocrates, Galen believed no difference existed between mental and physical illness[29] and noted that psychological stress could cause mental health issues. He is credited with the development of a tripartite theory of the soul, attempting to localize where the three parts were housed in the body: rational (brain), spiritual (heart), and appetitive (liver). In his book, On the Diagnosis and Cure of the Soul’s Passion, Galen discussed how to treat psychological problems, which some have called an early attempt at psychotherapy.[30] He directed people with psychological issues to share their deepest passions and secrets, which can help them feel better.

Treatment: Galen would have prescribed Jarrett a treatment plan similar to Hippocrates, with the addition of talk therapy.

Middle Ages

By the Middle Ages, supernatural explanations of mental illnesses resurfaced in Europe in an attempt to explain natural disasters, such as plagues and famines. In the 13th century, mentally ill people, especially females, were treated as demon-possessed witches. In the 16th century, Dutch physician Johann Weyer and Englishman Reginald Scot tried to persuade their populations that those accused of witchcraft were actually people with mental illnesses in need of help, but the Catholic Church’s Inquisition banned their writings. This practice did not decline until the 17th and 18th centuries. In the largest set of witch trials in America, between February 1692 to May 1693, more than 200 people were accused of being witches in Salem, Massachusetts; 20 were executed (14 females and 6 males), and others died in prison.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, asylums were created to house the mentally ill against their will. Inmates, many of whom were chained and beaten, often lived in squalor. Sometimes they were even exhibited to those willing to pay a fee. They were also subjected to a host of arcane medical practices, such as purging, blistering, or bloodletting.[31]

Treatment: Religious leaders may have attempted an exorcism on Jarrett, or physicians may have placed him in an asylum, where he would have been blistered, bled, or given laxatives.

18th and 19th centuries

In 1789, King George III of England descended into madness. His doctors were unable to say if he would recover or if someone else should replace him.[32] This crisis triggered physicians at England’s insane asylums to begin looking into the inheritance patterns of mental illness. Long before the discovery of DNA, doctors started collecting family histories of the insane, criminals, and those with intellectual disabilities among those in the asylums, prisons, and schools for “feebleminded” children. At the time, physicians who specialized in mental illness were called alienists because they treated people who were alienated from society. Some alienists thought stress caused mental illness, but most ascribed to the belief that it was transmitted through families by heredity.

Asylum directors started using family trees and surveys to study and track down affected relatives of their patients and institutionalized them as well, believing these people should be discouraged from reproducing. Asylum superintendents, legislators, and social reformers embarked on a deeply misguided eugenics movement to improve society by passing sterilization laws that were eventually supported by the US Supreme Court (1927 Buck vs. Bell case). They passed in 32 states and formed part of the rationale for Nazi Germany’s atrocities. This movement continued into the 1960s, with more than 60,000 Americans undergoing sterilization.[33]

In 18th-century Europe, protests broke out over the conditions in the asylums, and reformers aimed to end the abusive practices. They took the patients out of chains and encouraged good hygiene, recreation, and occupational training.[34] In the United States, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, physician Benjamin Rush, who is considered the father of American psychiatry, established a more benevolent approach, unshackling patients, forbidding beatings, and lobbying for improved living conditions in Pennsylvania.

This doesn’t mean that all of Rush’s therapies were helpful. In his book, Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind, he wrote that hypochondriasis, a form of melancholia or modern-day depression, needed to be treated by “direct and drastic interferences” that involved “assaulting the patient’s mind and body” in an attempt to reset their constitution.[35] He recommended that doctors “plumb” patients’ systems by bleeding (leeches), blistering, and cupping (similar to the current cupping trend that reached national attention when swimmer Michael Phelps was spotted at the 2016 Olympics with the telltale purple blotches on his back that arise from the treatment[36]). Rush also prescribed drugs, like mercury, arsenic, and strychnine —now known to be poisonous —to induce vomiting and diarrhea and suggested fasting for two or three days.[37] Once the body was cleaned out, he recommended stimulants, such as tea and coffee, ginger, and black pepper in large doses; magnesia, mustard rubs; hot baths to induce sweating followed by cold baths; and exercise.

When Abraham Lincoln was severely depressed in January 1841, his physician Dr. Anson Henry subscribed to Rush’s aggressive theories and likely subjected the future president to these punishing treatments. After Lincoln spent a week alone with Dr. Henry, he described himself “as the most miserable man living.”[38]

Rush also believed many psychiatric illnesses were the result of blocked circulation. To improve brain blood flow in schizophrenic patients, Rush would strap them into the “gyrating chair,” a device that spun them around until they became dizzy. It didn’t work.

In the 1770s, Europe was influenced by German physician Franz Anton Mesmer, who attempted to treat the “energy blockages” he believed were at the root of mental illness. He thought all illnesses could be attributed to an insufficient flow of what he called “animal magnetism.” By putting patients into a trance-like state and then probing certain body parts to restore energy flow, Mesmer drove his patients to states of crisis (delirium or seizures). In some patients, symptoms miraculously vanished after the treatment, rocketing Mesmer to celebrity status. In 1843, Scottish physician James Braid coined the term hypnosis for a technique originally derived from animal magnetism to induce hypnotic trances.

Treatment: Jarrett may have been institutionalized and sterilized, if not euthanized, and his family placed under suspicion. American physician Rush might have prescribed blistering and poisonous drugs like arsenic, followed by hot and cold baths. Germany’s Mesmer might have hypnotized Jarrett to relieve the blockage of energy.

FREUD AND PSYCHOANALYSIS

In the late 19th century, Viennese physician Sigmund Freud voyaged to Salpêtriere Hospital in Paris, where he studied with the founder of modern neurology Jean-Martin Charcot, who was best known for his work with hysteria and hypnosis. Charcot used hypnosis as a cathartic energy release to enable healing. Freud later abandoned hypnosis in favor of psychoanalysis, the talking cure, which dominated psychiatry for the first half of the 20th century.

Freud, a neurologist, was determined to understand the human mind. He tried to understand it from a neuroscience or brain perspective, but gave up in 1895, when he concluded that the science of his time was not up to the task of explaining patients’ symptoms. Eventually, he came to believe in the power of the subconscious, which could not be accessed during wakefulness but could be accessed in hypnotic trances and later through psychoanalysis. For Freud, the mind was like an iceberg —the largest part was unconscious and hidden from sight. He argued that the mind had three parts: (1) the id (child self, selfish desires, and instincts), (2) ego (adult self that helps control the id to make more rational decisions), and (3) superego (moral self that is the voice in your head judging your actions).

He developed the “talking cure” of psychoanalysis to help rid mentally ill patients of the internal conflicts between their id, ego, and superego, which he viewed as the cause of many mental illnesses. For example, if a man wants to steal from his employer (id), he may sublimate the desire by writing crime stories or deny the desire altogether. But what if these defense mechanisms (sublimation and denial) are not strong enough? Freud hypothesized the person may develop a psychiatric disorder. By encouraging people to talk about their hidden fears and desires, Freud believed he could lead them to a cure. He encouraged his patients to talk about everything that came to mind, including their dreams, then he would psychoanalyze them. He believed many conflicts typically started in childhood. Psychoanalysis provided the launching pad for hundreds of schools of psychotherapy and “talking cures” still in existence today, including behavior therapy; cognitive behavioral therapy; psychodynamic therapy; and marital, family, and group therapy.

Treatment: Freud may have had Jarrett lying on the psychiatrist’s couch four or five times a week, attempting to work out his internal conflicts.

KRAEPELIN AND THE BIOLOGICAL CAUSES OF MENTAL ILLNESS

A contemporary of Freud’s, German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin believed the primary cause of mental illness was biological with a strong genetic component. His theories were influential during the early 20th century and reemerged at the end of the 20th century when psychoanalysis fell out of favor. Viewing psychiatry as a branch of medicine, he began developing the modern classification system for mental disorders. He also protested against the inhumane treatments in psychiatric asylums and argued against alcoholism and capital punishment. He emerged as an advocate for the treatment, rather than the imprisonment, of the insane and rejected Freud’s psychoanalytical theories as unscientific, especially those suggesting that early sexual urges were the cause of mental illness.

Treatment: Kraepelin would have diagnosed Jarrett with a brain that was misfiring and attempted to find a biological cure.

Early 20th century

FEVER, INSULIN SHOCK, ECT, AND LOBOTOMY CURES

Austrian physician Julius Wagner-Jauregg experimented with curing psychosis by inducing fevers. Misguided, he infected his patients with a by-product of the bacteria that causes tuberculosis. It was not successful. Undeterred, he began to use malaria parasites in 1917 to treat psychotic patients suffering from syphilis. Fifteen percent of them died, and the rest contracted malaria, but the fevers did temporarily decrease their symptoms. Wagner-Jauregg was awarded the Nobel Prize for his research in 1927.

In 1927, another Austrian psychiatrist, Manfred Sakel, administered large doses of insulin to purposely cause seizures in psychotic patients. Researchers discovered that if blood glucose levels went too low, people fell into a coma or experienced seizures, and this could temporarily alleviate symptoms. Unfortunately, the treatment was associated with negative side effects, such as obesity, and more severe consequences, including brain damage and even death.

In 1938, Italian neurologists Ugo Cerletti and Lucino Bini were the first to deliver electric shocks to patients to induce seizures. They found that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) had more lasting benefits than insulin-shock therapy with fewer side effects. ECT is still used today to treat severe cases of schizophrenia, depression, mania, and serious suicidal thoughts.[39] With anesthesia, muscle relaxants, and more targeted dosing, it can be an effective technique, but it can also cause memory problems, confusion, headaches, and muscle aches.

In 1935, Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz drilled holes into the skulls of 20 mentally disturbed patients and used a wire in 13 of them to sever the connections in the brain’s frontal lobes. Moniz was hoping the procedure, called a lobotomy, would calm his patients, who suffered from anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia. It worked! Patients became more compliant, spurring wide adoption of the procedure, which was subsequently used on thousands of patients. Over time, however, it became apparent that it destroyed personalities and turned people into zombie-like beings. Despite these alarming side effects, Moniz also received a Nobel Prize for his work.

Treatment: Wagner-Jauregg would have given Jarrett malaria in an attempt to heal him. Sakel would have tried insulin-shock therapy on Jarrett. Cerletti and Bini would have subjected Jarrett to electric shock therapy to reset his brain. Moniz would have performed a frontal lobotomy on Jarrett, calming his aggression but permanently damaging his personality.

Today, there is a renaissance of surgical techniques for psychiatric illnesses, but they are very different from the frontal lobotomy of old. Very precise, nondamaging surgical interventions can be used to turn off or on certain circuits in the brain. This approach has been effective in Parkinson’s disease and has shown some efficacy for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and some patients with refractory depression.

Lobotomy: Surgically Damaging Frontal Lobes

LOBOTOMY: SURGICALLY DAMAGING FRONTAL LOBES

The late 20th century

THE MIND MEDICATION REVOLUTION

Despite psychoanalysis and the other techniques listed above, there was little hope for a cure for serious mental illnesses until the 1950s, when a host of psychiatric medications became available to practitioners and patients. The first effective medication for schizophrenia (chlorpromazine, brand name Thorazine) was developed in 1951 to treat nausea and allergies and to calm patients before surgery. When it was administered to a hospitalized violent young man, it immediately calmed him and caused such an improvement in his behavior, he was discharged a few weeks later. Chlorpromazine and subsequently other antipsychotic medications, which reportedly block excessive dopamine in the brain, led to dramatic improvements for many psychotic patients and ultimately to a significant reduction in state hospital populations.

The 1950s also saw the release of methylphenidate (Ritalin), which soon was prescribed to help hyperactive children; chlordiazepoxide (Librium), the first benzodiazepine, for anxiety disorders; and imipramine (Tofranil) for severe depression. The age of psychopharmacology had begun in earnest, with medications for bipolar disorder, OCD, and other disorders flooding the market in the decades that followed.

While I was in medical school, Xanax was released for panic disorders with the erroneous notion that it was less addictive than Librium and the other benzodiazepines. Since it was new, psychiatric residents prescribed it a lot, which is something I later regretted when I saw what it did to SPECT scans. Plus, whenever I prescribed it to patients, I found it was incredibly hard for them to get off it.

In 1987, with the FDA approval of the blockbuster antidepressant Prozac (fluoxetine), the mind drug revolution began to dominate psychiatry. Reportedly, Prozac had fewer side effects than imipramine and medications like it, leading to other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs) antidepressant medications being approved for depression. Since Prozac was introduced, antidepressant use in the United States has increased 400 percent, and more than one in 10 Americans now takes one. Only medications to lower cholesterol are prescribed more often than antidepressants in the United States.[40]

After the global success of Prozac, the “chemical imbalance” theory of mental illness burst into the public consciousness, and many people began proactively asking their doctors to fix their down moods. Famously, after actress Carrie Fisher was cremated, her ashes were placed in a green and white Prozac-pill shaped urn.

Since Prozac was introduced, antidepressant use in the United States has increased 400 percent, and more than one in 10 Americans now takes one.

Taking pills may seem like an easier and quicker solution to bad moods than taking the time and effort to develop brain-healthy habits, build skills, or change troublesome behavior. Yet there is a dark side to the mind-meds that is often overlooked. Thousands of lawsuits claim that Prozac and other psychiatric medications increase violent or suicidal behavior. Virtually all antidepressants and antipsychotic medications have black box warnings, which, in simple terms means the FDA cautions patients in the strongest terms to pay close attention to potentially extremely harmful or dangerous threats to their health.

In 1991, just when I was beginning to use brain SPECT imaging, reports surfaced suggesting Prozac increased violent behavior. When it happened to one of my patients, it horrified me. It caused us to start reviewing scans to see if we could predict which scan patterns were associated with medications making patients worse, such as the negative reaction Jarrett had on multiple stimulants. We have published papers on ADD/ADHD[41] and depression,[42] revealing the SPECT patterns that are associated with both positive and negative responses to medications.

Despite the problems, the pharmaceutical industry is incredibly successful at marketing psychiatric medications to doctors and the general public. From 1997 to 2016, the industry increased direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising from $1.3 billion to $6 billion.[43] Prescription drug ads often do not adequately explain side effects, and because of repeated exposure, many people tune out those statements at the end of TV commercials, often delivered in a rapid-fire manner, such as, “This drug may cause permanent liver damage, seizures, an allergic reaction that leads to fatal throat swelling and suicidal tendencies.” Patients in the United States are more than twice as likely to ask for drugs seen in ads compared with those in Canada, where most direct-to-consumer advertising is prohibited.[44]

There is no doubt in my mind that psychiatric medication saves lives, especially for people who have the more serious brain-health/mental-health disorders, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Yet we should all be cautious with meds because, once they are started, they are hard to stop,[45] and they do not just reset your brain; they change it. An Oxford University study found most SSRIs —such as Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, and Lexapro —do not just decrease negative emotions; they reduce all emotions, including love, happiness, and joy. Participants felt separated from their surroundings and cared less about important things in their daily lives. They felt like their personalities had changed.[46]

Treatment: Even though Jarrett had failed five prescription medications before seeing us, other doctors would continue the trial and error method of trying to get his symptoms under control.

THE DSM: A MORE SCIENTIFIC APPROACH?

In an effort to adopt a more objective and scientific approach and to increase standardization in a field that struggled with credibility, in 1952, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) released the first version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I), which categorized all mental disorders. Initially modeled after diagnostic tools used by the military and Veterans Administration, the DSM has since undergone revisions resulting in five subsequent editions (DSM-II 1968, DSM-III 1980, DSM-IIIR 1987, DSM-IV 1994, and DSM-V 2013). The DSM has had great success and nearly all mental health professionals in the United States and many around the world use it. Yet it is not without controversy.

In a 2005 lecture at the annual meeting of the APA, Thomas Insel, one of the most powerful psychiatrists in the world at the time as director of the National Institutes of Mental Health, caused an uproar when he announced the DSM was 100 percent reliable . . . but zero percent valid, meaning if you make a diagnosis with the criteria today for a certain disorder, like depression, you will make it again tomorrow, but zero percent valid because it is not based on any underlying neuroscience.

After the DSM-V was released in 2013, Insel posted a blog:

The goal of this new manual, as with all previous editions, is to provide a common language for describing psychopathology. While DSM has been described as a “Bible” for the field, it is, at best, a dictionary, creating a set of labels and defining each. The strength of each of the editions of DSM has been “reliability” —each edition has ensured that clinicians use the same terms in the same ways. The weakness is its lack of validity. Unlike our definitions of ischemic heart disease, lymphoma, or AIDS, the DSM diagnoses are [not] based on . . . any objective laboratory measure. . . . Patients with mental disorders deserve better.[47]

After using a number of the DSM versions on thousands of patients over the past 40 years, it is clear to me that it can help us categorize illnesses such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, panic disorder, or borderline personality disorder, but it doesn’t tell us anything about what causes them or how to predict which treatments will work because, as Insel suggested, it is not based on any underlying neuroscience.

What’s more, each new version of the DSM adds additional mental disorders, which leads to an increase in the number of people diagnosed with problems —a concept called medicalization, where, in a given year, about one in five Americans will suffer from at least one DSM disorder.[48] Contrast that with rates from the 1950s when far fewer people were being diagnosed each year. The more disorders that are included in the DSM, and the more lenient their definitions, the easier it is to diagnose healthy people as having a problem. Predictably, the increase in “sick” people correlates with an increase in treatment, especially medications.

Treatment: Jarrett had been diagnosed with DSM-IV ADHD since the age of three, but none of the standard medications recommended had worked. In fact, they all made him worse.

THE 15-MINUTE MED CHECK

When I was in training in the late 1970s to mid-1980s, psychiatrists were able to spend time with patients. If patients needed to be hospitalized, psychiatrists could treat and stabilize them over weeks or months. In outpatient settings, psychiatrists performed both psychotherapy and medication management, often seeing patients one to two times a week. In the early 1990s, when managed health care became more popular, insurance companies began to dictate how long patients could stay in the hospital and how many sessions they could have with therapists. Having been in the trenches at the time, it seemed to me that many of their decisions were based not on patient need but on attempts to optimize company profits.

Over the years, professionals have been squeezed to see more patients in less time in order to make enough money to pay back their student loans and support their families. Less trained and less expensive professionals were doing more therapy and psychiatrists were relegated to 15-minute monthly med checks. As med checks increased, so did the use of psychiatric medication, in part because it was the unique tool psychiatrists had in their toolboxes. As a side effect of the 15-minute med check, psychiatrists became more disconnected from the intimate details of patients’ lives.

Treatment: Jarrett and his parents had seen 5 different doctors who all practiced with the 15-minute med check model. It was not helpful.

The 21st century

NONPSYCHIATRIC PHYSICIANS, NURSE PRACTITIONERS, AND PHYSICIAN ASSISTANTS ARE NOW WRITING MOST OF THE PRESCRIPTIONS TO MANAGE YOUR MIND

One of the most disturbing trends is that nearly 85 percent of psychiatric medications are prescribed by primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in short office visits, and 72 percent of these prescriptions are accompanied by no diagnosis in the charts.[49] These medical professionals often do not have the time or the specialized training to develop comprehensive treatment plans or to tell you about safer and more natural solutions. Some primary care physicians do a wonderful job handling mental health issues, while others cause more harm than good.

Treatment: Many patients like Jarrett start by getting prescriptions from their family physicians or pediatricians. Sometimes this is helpful, sometimes not.

TRANSCRANIAL MAGNETIC STIMULATION (TMS)

TMS is a newer treatment to change the brain for the better. It uses brief magnetic pulses to stimulate activity in the areas of the brain known to affect mood, anxiety, and pain. This is not the same as ECT from the 1930s. TMS does not require anesthesia, plus it’s less expensive and has fewer side effects than ECT. An Israeli study showed that TMS and ECT have similar efficacy.[50] The FDA has approved TMS for the treatment of resistant depression, but new evidence shows it can enhance memory and potentially help improve a wide range of other brain-related issues, including depression;[51] anxiety;[52] addiction;[53] smoking cessation;[54] post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD);[55] OCD;[56] cognitive problems, memory, and dementia;[57] and tinnitus (ringing in the ears).[58] At Amen Clinics, we use TMS differently than most of our colleagues. We change the settings based on what we see from our brain imaging work. Doing the same treatment settings for everyone is like giving every depressed patient the same medication, which seems to work about as well as giving a placebo.

Treatment: Jarrett may have tried a course of TMS.

MARIJUANA AND PSYCHEDELICS

The current trend, besides pharmaceutical medication, is using marijuana and psychedelic drugs —such as LSD, ketamine, psilocybin mushrooms, ecstasy, ayahuasca, and ibogaine —to treat psychiatric illnesses. At the time of this writing, using marijuana for at least medical purposes is legal in 30 states, with more on the way. As the perception of the danger of a drug goes down, its use goes up. Many clinicians are now prescribing marijuana and CBD (cannabidiol, one of the ingredients of the marijuana and hemp plants) oil to help patients with anxiety, depression, irritability, and aggression despite limited research. This new market has made many marijuana millionaires with an exuberance rarely seen. The FDA recently approved a cannabidiol solution, Epidiolex, for two seizure disorders.

Our brain imaging work over the last 30 years has given me pause in regard to marijuana, and at the time of this writing, the jury is still out for me on CBD. Over the last 30 years, I’ve seen thousands of SPECT scans of patients who were regular marijuana users. In 2016, my colleagues and I published a study on more than 1,000 marijuana users and showed that virtually every area of the brain was lower in blood flow compared to healthy scans, especially in the hippocampus, one of the brain’s major memory centers.[59] In 2018, we published the world’s largest brain imaging study on 62,454 SPECT scans on how the brain ages. Marijuana was associated with accelerated aging in the brain.[60] So caution is needed.

Other professionals are also studying and using psychedelics for addictions and depression, especially ketamine. Due to its hallucinogenic effects, ketamine has a reputation as a popular and illicit party drug, going by the nickname “Special K.” It dulls pain and users often feel detached or dissociated from their own body. First developed in the 1960s, ketamine was administered as an anesthetic and given to soldiers during the Vietnam War. In 2000, researchers started studying ketamine as a treatment for depression and discovered that it improves mood much faster than traditional antidepressant medications, and sometimes works when other drugs have failed. More than a hundred studies have shown that ketamine has antidepressant effects.[61] Unlike antidepressants, which work by enhancing neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, ketamine is thought to change the way brain cells talk to each other —similar to a computer reboot or hardware fix. Ketamine is showing potential, but a new study argues for caution. It showed that the antidepressant effects of ketamine were eliminated with the opiate blocker naltrexone, meaning it worked by activating the opiate centers of the brain.[62] In the long run, could it have similar damaging effects as other opioids and be causing more harm than good?

Treatment: As Jarrett became an adult, his doctor may have treated him with marijuana or ketamine.

INSANITY IS OFTEN DESCRIBED AS DOING THE SAME THING AND EXPECTING A DIFFERENT RESULT:

The Psychiatric Diagnostic and Treatment System Needs a New Paradigm

When President Barack Obama called for more mental health services[63] after 20-year-old Adam Lanza murdered his mother and went to the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, where he fatally shot 20 six- and seven-year-old children and six adults, I knew that if we spent more money using the same symptom-based diagnostic and treatment model, we would still get the same disturbing results. Like Lanza, a number of our nation’s most notorious mass shooters had seen psychiatrists or mental health professionals and had received “standard of care” treatment before their crimes, including Kip Kinkel (Springfield, OR, 1998), Eric Harris (Columbine, CO, 1999), Seung-Hui Cho (Virginia Tech, 2007), James Holmes (Aurora, CO, 2012), and Nikolas Cruz (Parkland, FL, 2018).

We do not need more of the same. We need a completely different paradigm rooted in neuroscience and hope. A new way forward in psychiatry will require ending the paradigm of mental illness, because psychiatric issues really are so much more. Your brain creates your mind. The issues that affect our minds stem from our brains, our bodies, our thoughts, our social and work interactions with others, and our deepest sense of meaning and purpose. We were able to help Jarrett change the trajectory of his life by addressing all of these factors in an integrative way. It started by looking at his brain, because if you never look, you never really know.