When Tim Wu coined the term network neutrality in 2002, the concept was less a fully formed political demand than a proposal for managing network traffic. Yet it was the term that open internet activists—much to their initial chagrin—would be stuck with. Joshua Breitbart lamented in 2006, “Progressives trying to protect the Internet from corporate hijacking have once again shot themselves in the foot by trying to rally people around ‘net neutrality.’ Only a Democrat would think people could get excited about neutrality. What’s the opposite of ‘neutral’? Non-neutral … Partisan … In gear … ?” Arianna Huffington, co-founder of the liberal blog the Huffington Post, asserted that the term net neutrality was akin to “marketing death” and that the idea desperately needed to be rebranded.1 For those concerned about the fate of the open internet in the mid-2000s, “net neutrality” was a soporific expression that only a network engineer or policy wonk could love.

This anxiety over the phrase pointed toward a much more substantive fear: that net neutrality would remain an arcane, technocratic debate between, on the one hand, a small vanguard of technologists and media activists and, on the other, a large army of handsomely paid lobbyists for the telecom and cable industries. This concern was well founded, at least initially. According to a 2006 poll, only 7 percent of Americans had even heard about net neutrality.2

However, over the next decade, millions of Americans came to rally behind the cause of net neutrality. At times, the public’s support for net neutrality has become so widespread that policymakers and other Washington insiders have openly pined for the days when they could make critical decisions about the future of the internet without so much public scrutiny. One particularly exemplary report in this regard was published by the industry-funded Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) in 2015, in which the authors wistfully reminisced: “There was a time when technology policy was a game of ‘inside baseball’ played mostly by wonks from government agencies, legislative committees, think tanks, and the business community.” For these policy elites, rational public policy can come about only in the absence of the demos. But now, thanks to widespread mobilization around policy issues such as net neutrality and SOPA/PIPA (Stop Online Piracy Act / Protect Intellectual Property Act), the barbarians are at the proverbial gates: “Tech policy debates now are increasingly likely to be shaped by angry, populist uprisings.”3

Over the last fifteen years, net neutrality has sometimes been a marginal issue on the public agenda. During these relatively quiet periods, powerful actors on both sides of the debate, including ISPs, large internet companies, lobbying groups, unions, and advocacy organizations, maneuver behind the scenes to influence policymakers. These periods generally favor corporate opponents of net neutrality, who prefer to conduct their affairs outside of public purview. However, there have been a number of flash points scattered throughout the duration of the net neutrality battle—usually in anticipation of or in response to an FCC decision—that give rise to heightened public interest and activism.

This chapter examines four key phases of net neutrality activism: the initial period of mobilization in 2006, the fallout from the Google-Verizon net neutrality compromise in 2010, the activism that followed the repeal of net neutrality rules by a federal appeals court in 2014, and the push back against the FCC’s decision to repeal net neutrality in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election. We pay particular attention to the ways that activists have broken the net neutrality debate out of the narrow confines of elite institutions—including official government policymaking bodies, corporations, and think tanks—and transformed the issue into an object of mass democratic political action. Net neutrality activism is not only about securing more just and equitable policy outcomes—it is also about democratizing the policymaking process itself.

Net neutrality emerged amid the decline of the open-access movement. Just months after the Supreme Court’s 2005 Brand X decision signaled the death knell of open access, SBC’s CEO Ed Whitacre hinted that he expected internet companies like Google and Yahoo! to pay SBC for bringing their content into the homes of his company’s subscribers: “What they would like to do is use my pipes for free, but I ain’t going to let them do that because we have spent this capital and we have to have a return on it.”4 Whitacre’s brazen remarks affirmed the worst fears of media activists: that internet service providers were planning to create a tiered, pay-to-play internet. It was the first public attempt by ISPs to “double-dip” by charging both their subscribers and internet content providers to access each other. This catalyzed many politicians and media activists to redouble their efforts to rein in the broadband cartel. Beginning with the introduction of the Internet Freedom and Non-discrimination Act (S. 2360) by Senator Ron Wyden (D-Oregon) on March 2, 2006, a flurry of net neutrality legislation was proposed in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Much weaker proposals by congressional Republicans and pro-telecom Democrats would wend their way through Congress as well, most notably the Communications Opportunity Promotion and Enhancement (COPE) Act.

The driving force behind the burgeoning net neutrality movement was Free Press, a media reform organization founded in 2003 by media scholar Robert McChesney, progressive journalist John Nichols, and veteran activist Josh Silver, who served as the first president and CEO of the organization.5 Free Press was the central organizing body behind the Save the Internet coalition, which comprised over eight hundred pro–net neutrality groups. Free Press aggressively fought to assemble a politically diverse left-right coalition that included liberal groups such as MoveOn.org, Feminist Majority, and the American Civil Liberties Union as well as conservative organizations such as the Christian Coalition of America, the American Patriot Legion, and Gun Owners of America.

These groups tended to frame net neutrality primarily as a free speech issue, as a way to prevent ISPs from acting as gatekeepers of the online public sphere. “Internet freedom” became a rallying cry for the nascent movement. MoveOn warned its members, “Internet freedom is under attack as Congress pushes a law that would give companies like AT&T the power to control what you do online.”6 On the other side of the political spectrum, Roberta Combs, president of the Christian Coalition of America, rhetorically asked: “What if a cable company with a pro-choice Board of Directors decides that it doesn’t like a prolife organization using its high-speed network to encourage pro-life activities? Under the new rules, they could slow down the pro-life web site, harming their ability to communicate with other pro-lifers—and it would be legal.”7

The Save the Internet coalition also included large internet-based corporations such as Google, Amazon, and eBay. In contrast to many of the public interest organizations that participated in the Save the Internet coalition, corporations like Google foregrounded the ability of ISPs to suffocate innovation and entrepreneurship. The threat posed by ISPs to democratic speech rights was usually of secondary concern to them. Although these companies indulged the free speech rhetoric of their coalition partners, their primary motivation for supporting net neutrality was every bit as self-interested as the ISPs’ motivation for opposing it. The difference was that companies like Google and Amazon were initially perceived by many supporters of net neutrality as fairly benign—or even benevolent—actors compared to Comcast or AT&T.

The Save the Internet coalition’s corporate-activist alliance hinged on the understanding that the financial interest of large internet companies in net neutrality was broadly in harmony with the public’s interest. Some leading activists sought to appeal to diverse coalition members—including industry partners—by emphasizing how the loss of net neutrality might prevent the next Google or eBay from having a fair chance at getting started online.8 During this early phase of the net neutrality battle, it seemed politically beneficial for activists to couch some of their rhetoric in pro-business language and to have a corporate titan or two on their side. Though large corporations such as Google did not fund Save the Internet, their participation in the coalition did confer a degree of political legitimacy to its grassroots coalition partners.

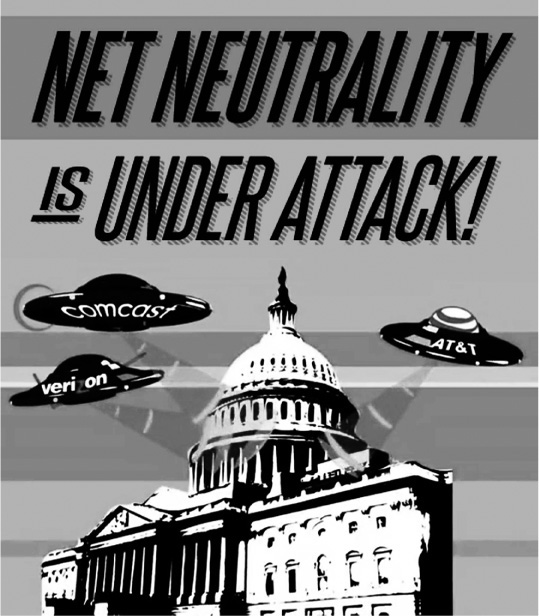

Within just a few months, activists began to transform net neutrality from an abstruse, technocratic debate into a cause with broad, even populist, appeal. Populism brings diverse groups together by emphasizing the binary opposition of “the people” to a common enemy, in this case the large, commercial internet service providers and the politicians who do their bidding in Washington.9 The populist understanding of net neutrality that was fashioned during this early period of activism in 2006 focused not on the technical minutiae involved in the net neutrality debate but on the fundamental antagonism between ISPs and the digital public—broadly construed to include not only ordinary internet users but also internet companies like Google. For example, in December 2006 Save the Internet released a four-minute viral video on YouTube entitled Independence Day. The narrator defines net neutrality as a sort of defense of the populist “everyman.” “Whether it’s … everyday citizens or a business tycoon: everybody’s website gets the same speed and quality. That’s called net neutrality.” Later in the video, as the narrator explains how ISPs are plotting to roll back net neutrality, flying saucers bearing the corporate logos of Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T hover around on the screen and shoot laser beams at the United States Capitol Building before moving on to attack various state legislatures. These internet service providers are depicted not only as enemies of American democracy but as external to the body politic—literally alien to it.10

Perhaps the single most important turning point of the 2006 net neutrality debate was the result of an error committed by Alaskan senator Ted Stevens—a blustering, crotchety lifelong politician who, as chairman of the Senate’s Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation wielded more influence over internet policy than perhaps anybody else in Congress at the time. In June 2006, Stevens gave a rambling eleven-minute speech against net neutrality on the Senate floor: “I just the other day got an internet [that] was sent by my staff at ten o’clock in the morning on Friday, and I just got it yesterday! Why?!” Stevens punctuated his wandering tirade with a now-infamous metaphor: “The internet is not something you just dump something on. It’s not a big truck. It’s, it’s a series of tubes!”11

Stevens’s remark that the internet was a “series of tubes” was a gift to satirists and supporters of net neutrality alike. Within days of the senator’s gaffe, millions of citizens learned about the public benefits of net neutrality. The audio clip of his comments ricocheted throughout the blogosphere, turning Stevens into an object of merciless ridicule. One entrepreneurial internet user even remixed the senator’s speech into a three-minute techno music video that was posted on YouTube. On The Daily Show, Jon Stewart joked that Stevens’s “series of tubes” comment “sounded like something you’d hear from, let’s say, a crazy old man in an airport bar at 3am [rather] than the Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee.”12

Poster, based on Save the Internet’s 2006 video Independence Day, showing three of America’s largest internet service providers attacking the United States Capitol Building. (Courtesy of Free Press.)

The snarky blog posts, video remixes, memes, and other parodies of Ted Stevens were effective not because they presented a cogent, rational argument in favor of net neutrality but because they foregrounded a visceral truth about American politics: policy is often not decided by those who are the most knowledgeable about an issue but by those who are most willing to serve corporate power (indeed, Verizon and AT&T were the first- and third-largest contributors to Senator Stevens’s 2008 reelection campaign, respectively).13 Senator Stevens’s almost cartoonish performance on the Senate floor, coupled with the satirical depictions of it circulating on the internet, wiped out any pretensions to the contrary. As Peter Dahlgren argues, this kind of humorous commentary works to “strip away artifice, highlight inconsistencies, and generally challenge the authority of official political discourse.”14

Ultimately, none of the net neutrality legislation that was introduced in 2006 was passed into law. However, this initial wave of activism lifted net neutrality from a place of relative obscurity into the national spotlight. Politicians were quickly forced to take a public stance on the issue. During the height of net neutrality activism in 2006, then senator Obama announced his support for net neutrality on a podcast: “We can’t have a situation in which the corporate duopoly dictates the future of the Internet, and that’s why I’m supporting what is called net neutrality.”15 During his presidential campaign the following year, Obama told a crowd at Google, “I will take a backseat to no one in my commitment to network neutrality.”16

Barack Obama took office in 2009 with a strong public mandate to implement net neutrality. Yet this early momentum was largely squandered by the Obama administration, which failed to translate the president’s ambitious campaign rhetoric into strong net neutrality policy. The new chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, Julius Genachowski, approached the issue with caution. Rather than simply pass net neutrality regulations over the objections of internet service providers, in June 2010 Genachowski attempted to broker a closed-door agreement between large internet companies and ISPs that would be amenable to each of the stakeholders. The process collapsed in early August 2010 when Google and Verizon—former archenemies on the issue of net neutrality, ostensibly representing the two sides of the debate—bypassed the FCC and announced that they had privately arrived at a “legislative framework” for proceeding forward with net neutrality. The Google-Verizon proposal was riddled with loopholes, stripped the FCC of much of its regulatory authority over the wired broadband industry, and conveniently excused wireless internet providers from having to abide by net neutrality.

The Google-Verizon pact was a paradigmatic example of corporate libertarianism, with two of the nation’s largest tech behemoths telling the FCC how they would like to be regulated. The joint proposal granted Verizon and other wireless providers the right to throttle their users’ internet traffic as long as they were transparent about it. Google, on the other hand, also stood to benefit from the arrangement. Google was trying to make its then little-known mobile operating system, Android, a major player in the mobile world. The year before, Google had reached an agreement with Verizon to run the Android operating system on Verizon’s smartphones. The 2010 agreement aimed not only to cement Google’s budding partnership with Verizon but to earn goodwill from other wireless carriers in hopes of expanding Android’s footprint. Although the Google-Verizon treaty held no de jure significance, it nevertheless became the cornerstone of the FCC’s 2010 Open Internet Order. As a result of Google and Verizon’s joint lobbying efforts, wireless carriers were largely exempted from the order.

The reaction to the announcement of the agreement by Google’s erstwhile allies in the Save the Internet coalition was swift and severe. The coalition quickly issued a joint press release rebuking the accord: “The Google-Verizon pact isn’t just as bad as we feared—it’s much worse. They are attacking the internet while claiming to preserve it. Google users won’t be fooled.”17 As British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig was leaking millions of gallons of crude into the Gulf of Mexico, Free Press senior adviser Marvin Ammori remarked, “You have to hand it to Google. Going from ‘Don’t Be Evil’ to ‘Greedier than BP’ overnight is a pretty impressive trick.”18

Mobilizing with less than twenty-four hours’ notice, on August 13 protestors peacefully descended upon Google’s corporate headquarters in Mountain View, California. James Rucker, the co-founder of the civil rights organization Color of Change, entered Google’s building to deliver a petition signed by three hundred thousand people condemning the company’s about-face on net neutrality. Outside the GooglePlex, protestors held signs reading, “Google is evil if the price is right” and “No payola for the internet.” The Raging Grannies—an activist group comprising grandmothers who stage theatrical demonstrations at protest events—even led the crowd in singing “A Battle Hymn for the Internet.”

Members of the group Raging Grannies protesting outside of Google’s corporate headquarters in Mountain View, California. (Photo courtesy of Steve Rhodes.)

The 2010 Google-Verizon pact revealed the fragility and contradictions at the heart of the Save the Internet coalition. In contrast to most of the public interest groups and activists who supported net neutrality, Google’s commitment to protecting net neutrality was fleeting and transactional rather than one of principle. Since its inception, Google has proselytized about the virtues of the open internet in almost romantic terms. For example, in 2005 Google co-founder Sergey Brin waxed poetic: “Technology is an inherent democratizer. Because of the evolution of hardware and software, you’re able to scale up almost anything. It means that in our lifetime everyone may have tools of equal power.”19 However, lurking behind Google’s soaring rhetoric was always a business model. Net neutrality was essential to the company’s early success: without it, in the late 1990s ISPs could have crippled Google in its infancy by blocking or slow-laning traffic to its website or by cutting deals with larger, more established search engines like Yahoo! or MSN to prioritize their traffic.

By 2010, however, it was Google that was the entrenched incumbent. On the one hand, net neutrality protected Google from having to pay ISPs not to throttle its traffic. On the other hand, as Google became one of the largest and most profitable companies in Silicon Valley, it could afford to pay this extortion money; smaller companies looking to compete for Google’s market share would be less likely to be able to. Thus, repealing net neutrality would have cut into Google’s short-term profits, but potentially cemented its medium- and long-term dominance in search and other markets. As Google’s economic interest in net neutrality became more ambiguous, so too did its position on the issue.

After the DC Circuit Court struck down major provisions of the deeply flawed 2010 Open Internet Order in 2014, Tom Wheeler spent much of his first year as FCC chairman darting back and forth between the cable industry, internet companies, and the occasional public interest group in an ill-fated effort to triangulate his way to a solution that would be acceptable to everybody involved. Wheeler’s initial instinct was to strike a compromise with the broadband cartel, and he was hesitant to acknowledge what everybody else at the time knew (including the two other Democratic commissioners who served with him at the FCC): that the internet is a public utility, and that it ought to be regulated like one.

Frustrated by Tom Wheeler’s dithering approach, net neutrality activists put pressure on the FCC to reclassify broadband internet as a Title II telecommunications service. This was an ambitious goal at the time, in part because the FCC is a regulatory agency that is generally not as responsive to public pressure as members of Congress, who face reelection every two years. Even many activists fighting to reclassify broadband internet quietly believed that the FCC was unlikely to undertake such a bold move. Evan Greer, campaign director for the digital rights group Fight for the Future, reflected that in early 2014, “nobody thought these Title II net neutrality rules were a remote possibility.… I even sat across from an FCC commissioner who told me outright that it was never going to happen in this political environment.”20

The grassroots fight for net neutrality in 2014 and 2015 was led by Battle for the Net, a coalition of media advocacy groups. Three major organizations—Free Press, Demand Progress, and Fight for the Future—provided the coalition’s staff and funding.21 Other key participating groups were the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Avaaz, Public Knowledge, the American Civil Liberties Union, Center for Media Justice, Color of Change, the National Hispanic Media Coalition, and Common Cause, among many others.22 The role of corporations in the Battle for the Net coalition was far less significant in this iteration of the net neutrality saga than it was in 2010. Most notably, many of the Silicon Valley companies that had played a vocal, public-facing role in earlier net neutrality battles were incommunicado on the issue for most of 2014 (the exception being a somewhat perfunctory letter in support of net neutrality that was signed by some of the giants after they were shamed into doing so). Google CEO Eric Schmidt even went so far as to privately chastise members of the Obama administration for embracing Title II reclassification in 2015.23 As Google, Facebook, and eBay for the most part remained on the sidelines, Netflix became the new corporate face of net neutrality. Netflix was incited to action after Comcast and Verizon throttled Netflix video streaming in late 2013 and early 2014 (Netflix eventually agreed to pay off Comcast, Verizon, and most other major ISPs). Among the other companies that participated in the Battle for the Net actions in 2014 were Etsy, Kickstarter, and OkCupid.

Like the Save the Internet coalition, the Battle for the Net coalition mobilized a populist logic that positioned internet users against the greed of internet service providers. The Battle for the Net website described the fight for net neutrality in this way: “They are Team Cable … the most hated companies in America.… If they win, the Internet dies.… We are Team Internet.… We believe in the free and open Internet.”24

One of the most important ways that net neutrality activists were able to exert pressure on the policymaking process was by encouraging supporters to submit comments about Tom Wheeler’s net neutrality proposal to the FCC. The FCC’s old, labyrinthine website makes commenting on an issue a cumbersome endeavor even for many technologically savvy internet users. Battle for the Net, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and other organizations built much more user-friendly interfaces that could be used to submit comments to the FCC. Through email and social media, pro–net neutrality organizations encouraged their members to submit comments. By the end of the FCC’s comment deadline in September, over 3.7 million comments had been submitted. According to a study conducted by the Sunlight Foundation, less than 1 percent of the public comments that were submitted to the FCC during the four-month open-comment period supported Commissioner Wheeler’s plan to divide internet traffic into two speed tiers.25

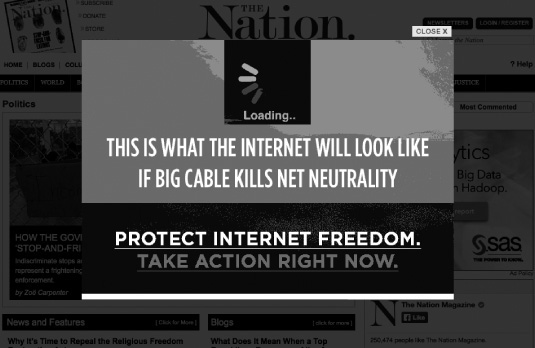

In an effort to illustrate the potential consequences of Tom Wheeler’s plan to allow fast lanes on the internet, the Battle for the Net coalition coordinated a series of protests dubbed Internet Slowdown Day. The organizers of the protest recruited websites to display the “spinning wheel of death” on their sites on September 10 in order to re-create the frustrating experience of waiting for websites to load and “remind everyone what an Internet without net neutrality would look like.” Over forty thousand websites participated in the protests, including Twitter, Netflix, Reddit, Tumblr, and Etsy.26 Visitors to these websites were prompted to contact their lawmakers to oppose the FCC’s proposal. Internet Slowdown Day generated more than 300,000 calls and 2 million emails to Congress, as well as an additional 777,000 comments to the FCC on September 10 alone.27

The Battle for the Net coalition was periodically able to translate its significant online presence into offline action as well. Throughout 2014, “Team Internet” organized on-the-ground protests in dozens of cities around the country. Drawing inspiration from the 2011 Occupy Wall Street protests, a small band of activists called Occupy the FCC set up an encampment outside FCC headquarters in Washington, DC, where they lived and protested for net neutrality for over a week. Many of these protests took direct aim at FCC commissioner Tom Wheeler. On the morning of November 10, demonstrators affiliated with the group Popular Resistance showed up at Tom Wheeler’s home and blocked his driveway. “We can’t let you go to work today because you work for Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T and not for the people,” one protestor told the noticeably agitated FCC chairman. The protestors then broke out into an updated rendition of the famous 1930s union song “Which Side Are You On?” “Which side are you on, Tom? Which side are you on? Are you with the people, Tom, or with the telecoms?”28

The Nation’s home page on Internet Slowdown Day, September 10, 2014. (The Nation Magazine, www.thenation.com, September 10, 2014.)

Despite the yeoman’s work performed by net neutrality activists throughout 2014, the most iconic moment of that year’s battle came from a comedian. On the June 1, 2014, episode of the HBO show Last Week Tonight, John Oliver opened by delivering a thirteen-minute diatribe about net neutrality that would reverberate throughout the internet over the coming weeks and months. Oliver’s defense of net neutrality departed from utopian visions of the internet as a Republic of Letters or an ennobled twenty-first-century public sphere, instead embracing a much more quotidian, even hedonistic understanding of the internet as a space of pleasure, rage, and indulgence: “Good evening, monsters. This may be the moment you’ve spent your whole lives training for … for once in your life, we need you to channel that anger, that badly spelled bile that you normally reserve for unforgivable attacks on actresses you seem to think have put on weight, or politicians that you disagree with, or photos of your ex-girlfriend getting on with her life.… We need you to get out there and, for once in your life, focus your indiscriminate rage in a useful direction. Seize your moment, my lovely trolls, turn on caps lock, and fly my pretties! Fly! Fly!”29

On YouTube alone, John Oliver’s video was viewed over 7 million times by January 2015, with the number of “likes” outnumbering the number of “dislikes” by a ratio of one hundred to one.30 Tom Wheeler himself saw the video and was visibly irritated by John Oliver’s jabs at his lobbying past. When asked about Oliver’s segment at a press conference, Wheeler shot back, “I am not a dingo,” referring to Oliver’s quip: “The guy who used to run the cable industry’s lobbying arm, is now running the agency tasked with regulating it. That is the equivalent of needing a babysitter and hiring a dingo.”31

Activist groups including Free Press emailed the Oliver clip to hundreds of thousands of people, further amplifying its reach. Thousands of people who watched John Oliver’s net neutrality rant also followed through on his call to flood the FCC’s website with comments. The FCC received 3,076 comments in the week before John Oliver’s net neutrality sketch aired—the week after, there were 79,838.32 The barrage of comments crippled the FCC’s aging online comment system, which was built on the assumption that only a small number of people—particularly lawyers representing industry groups, local government officials, and the occasional representative of a public interest organization—would be motivated enough to submit comments. The day after Oliver’s segment aired, the FCC’s website crashed. The FCC’s Twitter account announced: “We’ve been experiencing technical difficulties with our comment system due to heavy traffic. We’re working to resolve these issues quickly.”33

Without the mass public pressure that was brought to bear on him, it is unlikely that Tom Wheeler would have taken the bold step to reclassify broadband internet as a Title II telecommunications service. During his tenure as FCC chairman, Wheeler usually seemed hesitant to implement aggressive reforms, often deferring to the status quo. In the dominant narrative of the 2014 net neutrality battle, Chairman Wheeler’s decision to embrace Title II reclassification was a response to pressure from above. On November 10, 2014, days after significant midterm losses for the Democratic Party, President Obama circumvented the FCC and announced his support for strong net neutrality rules directly to the people via YouTube: “I’m urging the Federal Communications Commission to do everything they can to protect net neutrality for everyone. They should make it clear that whether you use a computer, phone, or tablet, internet providers have a legal obligation not to block or limit your access to a website.”34 While some observers decried the move as too little and too late, it was nonetheless a dramatic intervention by the president, and it arguably removed any remaining political cover for Wheeler to pass anything less than a strong net neutrality rule based on Title II protections.

While Obama’s “FDR moment” is sometimes pinpointed as the decisive turning point in the net neutrality fight, this assumption does not fully account for the political dynamics at play.35 Prior to the 2014 wave of activism, President Obama’s own support for net neutrality had waned. It was, after all, Obama who had appointed Tom Wheeler as chairman of the FCC the previous year, passing over outspoken consumer advocates such as Harvard Law School professor Susan Crawford, who was the preferred choice of many open internet activists. Obama even boasted that Wheeler “is the only member of both the cable television and wireless industry hall of fame. So he is like the Jim Brown of telecom.” Wheeler himself has suggested that his reversal was the result of his own hard thinking on the matter—a kind of “road to Damascus” conversion.

Ultimately, however, it was the uproar generated by activists and ordinary internet users over Chairman Wheeler’s proposal that was critical in securing net neutrality. While Wheeler certainly deserves credit for his willingness to change course and enthusiastically defend his position—referring to the passage of the 2015 Open Internet Order as the “proudest day in his public policy life”—he acted only after activists paved the way. Notwithstanding the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that prompted President Obama to come out so publicly, the strong net neutrality protections passed in 2015 were not simply the result of an inside game or conflicts among elites. More than anything, it was a battle fought for and won at the grassroots.

In recent history, few policies have enjoyed greater support than net neutrality. On December 12, 2017, the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland released a poll showing that a large majority of Americans wanted to keep net neutrality rules in place. According to the poll, 83 percent of the respondents opposed repealing net neutrality, including 75 percent of the Republicans who were surveyed, 89 percent of Democrats, and 86 percent of independents.36 Two days later, the FCC voted to repeal net neutrality in a 3–2 party-line decision. That such a popular piece of legislation would be repealed under the aegis of a “populist” president who ran on a pledge to “drain the swamp” is something of a tragicomedy. Indeed, Donald Trump’s approach to internet and telecommunications policy is thus far largely indistinguishable from the Republican old guard.

With the election of Donald Trump to the presidency on November 8, 2016, the fate of the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order was immediately imperiled. In a last-ditch effort to preserve net neutrality, a familiar coalition of advocacy organizations—including Fight for the Future, Free Press, Demand Progress, and the Center for Media Justice—coordinated the Internet-Wide Day of Action to Save Net Neutrality on July 12, 2017. The coalition employed many of the same tactics that participants used during the Internet Slowdown Day in 2014, including temporarily changing their websites to simulate what the internet could look like without net neutrality. For example, internet users who visited Reddit on the Day of Action were greeted with a message typed in a crawling speed that read: “The internet’s less fun when your favorite sites load slowly, isn’t it?” On the top left-hand corner of the website, Redditors inserted the mildly dystopian warning: “Monthly Bandwidth Exceeded, Click to Upgrade.”37

Meanwhile, Chairman Pai took to the internet for some activism of his own. Dressed in a Santa suit and wielding a lightsaber, he starred in a bizarre video produced by the conservative news site The Daily Caller entitled 7 Things You Can Still Do on the Internet After Net Neutrality. The video stunt was met with immediate contempt by the digital public. On Twitter, the actor who played Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars film series, Mark Hamill, cracked that Pai was “profoundly unworthy [to] wield a lightsaber” because “a Jedi acts selflessly for the common man—NOT lie [to] enrich giant corporations.”38 Pai’s streak of bad publicity worsened when it was revealed that he had collaborated on the video with a producer named Martina Markota, best known at the time for having helped propagate “Pizzagate,” a conspiracy theory that Hillary Clinton and other high-ranking Democratic officials were operating a child-trafficking ring out of the basement of a dingy Washington, DC, pizzeria.39

Many of the large tech companies that were at the helm of previous actions to defend net neutrality distanced themselves from the 2017 protests. Google’s participation was limited to a short, poorly publicized blog post on its policy blog. Facebook’s advocacy consisted of posts by CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg on their personal Facebook pages. Even Netflix, which just three years before had positioned itself as a stalwart defender of net neutrality, made it known that its commitment to net neutrality was largely circumstantial. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings explained in May 2017, “We think net neutrality is incredibly important,” but it is “not narrowly important to us because we’re big enough to get the deals we want.”40

FCC chairman Ajit Pai dressed in a Santa Claus costume holding a fidget spinner and toy gun in The Daily Caller’s video 7 Things You Can Still Do on the Internet After Net Neutrality. (The Daily Caller.)

Despite lackluster support from erstwhile corporate allies, net neutrality supporters are continuing the fight on a number of fronts, including in the courts. The major court case, Mozilla v. FCC, was brought before the DC Circuit Court of Appeals on February 1, 2019, by media reform organizations, internet companies including Mozilla and Etsy, and the attorney generals of twenty-two states and the District of Columbia. One argument they are making is that the FCC’s decision to throw out net neutrality violated the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act, which bans federal agencies from making “arbitrary and capricious” policy changes.41 Net neutrality advocates contend that the FCC’s decision to repeal the 2015 Open Internet Order just three years after it was passed was based not on a careful assessment of the effectiveness of the law but on the ideological whims of the FCC’s newly minted Republican majority.

In the spring of 2018, Senator Ed Markey spearheaded a Hail Mary effort in the Senate to prevent the repeal of net neutrality from going into effect through the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to reverse recent decisions by government agencies with a simple majority in the House and Senate coupled with the president’s approval. Although the measure passed 52–47 in the Senate—a remarkable feat considering that Republicans controlled the chamber—it failed to garner a majority of support in the Republican-controlled House. After the 2018 midterm elections, Democrats took back the House, bolstering the number of pro–net neutrality members of Congress. Nonetheless, President Trump would likely veto such a resolution if it were to reach his desk.

Absent action to reinstitute net neutrality at the federal level, activists have engaged in a state-by-state fight to reimplement net neutrality. As of February 2019, ten states have enacted net neutrality legislation, while more than twenty others are considering it. On September 30, 2018, California passed a net neutrality bill that the Electronic Frontier Foundation called the “gold standard” of state net neutrality laws. In fact, California’s bill goes even further than the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order.42 In addition to restoring rules against blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization, California’s bill also forbids ISPs from engaging in a controversial practice called zero-rating, which was permitted under the previous net neutrality rules. Zero-rating allows ISPs to exempt certain websites or applications from counting toward users’ data charges. This gives ISPs the power to make it easier and cheaper to access websites they favor and more expensive to access those they disfavor.

If California’s net neutrality bill is successfully implemented, its impact could reverberate across the country. Enacting strong net neutrality regulations in the country’s most populous state could push broadband providers to abide by net neutrality principles even in states with weak or nonexistent net neutrality laws. Rather than adopting a different approach to net neutrality in every state they operate in—a costly, logistically complicated, and technically complex endeavor—internet service providers may be pressured into bringing their traffic management practices into line with California’s standards.

These state-led efforts to protect net neutrality have been met with fierce opposition from the FCC, President Trump’s Department of Justice, and the broadband industry, which all insist that these rules are illegal. Yet their argument rests on shaky grounds. In voting to repeal net neutrality in December 2017, the FCC’s Republican commissioners claimed that the agency lacked the authority to enact federal-level net neutrality regulation. At the same time, the FCC is asserting sweeping authority to preempt state and local governments from creating their own net neutrality rules. The FCC cannot have it both ways. As Stanford Law professor Barbara van Schewick explains, “An agency that has no power to regulate has no power to preempt the states, according to case law.”43 Gigi Sohn adds: “The broadband providers say they don’t want state laws, they want federal laws. But they were the driving force behind the federal rules being repealed.”44

Indeed, the opposition to these state-led initiatives reeks of cynical political opportunism: for decades, Republicans have extolled the virtue of states’ rights and decried the excessive influence of the federal government on local affairs. ISPs and their political surrogates have also long mobilized states’ rights arguments in defense of the broadband industry’s interests, whether in opposition to federal net neutrality laws or in support of state bills prohibiting municipalities from building their own broadband networks to compete with large ISPs. Now, faced with a wave of state-led movements to protect net neutrality, ISPs insist that the fate of net neutrality should be decided by Congress rather than by state legislatures.

For the likes of Google, Netflix, and Facebook, the value of net neutrality is expressed almost exclusively in commercial terms. A 2017 report published by the Internet Association, the lobbying arm for companies such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook, summarized the net neutrality debate as follows: “Behind all the noise surrounding net neutrality, the debate boils down to … competition, investment, capacity, and innovation.”45 In this view, net neutrality is first and foremost a series of principles to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship on the internet. The public interest is either of secondary concern or—perhaps even more problematically—equated with the health of digital capitalism itself.

During earlier stages of the net neutrality debate, activists sometimes failed to distinguish their own political goals from those of Google, Netflix, and other fair-weather corporate crusaders for net neutrality. Too often they took on the pro-business arguments of their corporate counterparts, substituting rationales for net neutrality based on civil rights, free speech, and social justice for ones based on promoting innovation and entrepreneurship. There was a tendency to equate the public’s interest in net neutrality with the success of Google, Facebook, or the “next” new media titan, effectively entrusting the public good to private enterprise.

However, many activists no longer want to be coalition partners with Silicon Valley tech giants. Over the last decade, the likes of Facebook and Google have not just been fickle allies in the fight for net neutrality, they have also actively worked to undermine the open internet. There is growing public recognition that Facebook and Google are not neutral conduits of interpersonal communication and information exchange but rapacious corporations that are intent on monetizing their users’ privacy for commercial gain. Facebook and Google have helped transform the internet from what idealists in the first decade of the twenty-first century hoped would be a democratic public sphere into a commercialized panopticon littered with advertisements, clickbait, and misinformation. A broad-based movement for net neutrality therefore requires a much stronger ethical foundation than the business interests of Facebook, Google, and Amazon. At the forefront of the current wave of net neutrality activism are groups like the Center for Media Justice and Color of Change, which have reframed net neutrality as a civil rights and social justice issue rather than as an internecine quarrel between different segments of corporate America. Malkia Cyril, the executive director of the Center for Media Justice, explains, “This is not a fight between Comcast and Netflix. This is not a fight between the geeks and the nerds. This is a fight between ordinary people and our right to access a modern communications system in the twenty-first century and those who would like to discriminate and use that system for profit instead of for democracy.”46

Fundamentally, the fight for net neutrality is a fight for political power. In the age of Trump, net neutrality is of particular importance to the emerging democratic movements that are fighting on the front lines against the rising forces of racism, nativism, sexism, and economic exploitation that have been empowered by the Far Right. From Black Lives Matter to the #MeToo movement to the Dakota Access Pipeline protests (#NODAPL), digital tools, including social media platforms, offer activists an imperfect but efficient means to broadcast their message to the public. The utility of the internet to marginalized communities is, in part, dependent on net neutrality. As the media justice activist Steven Renderos argues: “In an era when immigrant and Muslim communities are being scapegoated by the White House, an open Internet protected by Title II is vital to preserving our democracy. When the Muslim Ban was announced, activists used the open Internet to mobilize millions at airports across the country.”47