Wang Di

She began in the first month of the lunar year. They said she was born at night, the worst time to arrive—used up all the oil in the lamp so that her father had to go next door for candles. It took hours, and it was only after muddying up swaths of moth-eaten sheets the neighbors had given in the last few weeks of her mother’s pregnancy that she emerged. As her first wails cracked through the hot air in the attap hut, he went into the bedroom to look at her, a worm of a thing freshly pulled out of the earth. When he saw the gap between the baby’s legs, the first-time father spat, then slumped in a chair at the kitchen table, eyeing his wife as she nursed, already thinking about the next child.

That is one story.

Or, she began when her mother found her in a rubbish skip. She was walking to the market with four eggs her hens laid that morning, was passing by the public bins when it started to whimper. The woman looked in and there it was—a child, scraps of leftover dinner on top of it. She took the baby home and brushed the dirt off her face. Waited for a week to see if anyone would come and claim her. They kept her when no one did.

The third and last story, told to the child by her aunt, was that she was born and her father took her to the pond, the one where water spinach grew. Villagers went to collect it in armfuls when they could afford nothing else for dinner, and it was by this vegetable, completely hollow in the middle of their stems so as to warrant the name kong sin, empty heart, that her father put her. The aunt told this story each time she went to visit, and each time, as she got to this point in the story of her niece’s birth, she would stop, smack her lips and lean in close, adding that her father had tried to push her under with the tip of his sandaled feet. She explained that it wasn’t easy, what he was doing, because the water was shallow and the weeds were holding her up.

“You were bobbing in and out of the water,” she said, “and the whole business was almost finished with when you stopped crying from the feeling of damp on your body and simply looked at him. Your eyes opened up a crack and you just stared into his face.”

The aunt couldn’t say why but it made the new father take the child back home again. He put the bundle on the table like a packet of biscuits and told his wife that she could keep her if she gave birth to a baby boy next year. They didn’t bother naming the girl for a few weeks, but when they did, they named her Wang Di—to hope for a brother.

This morning, as with most mornings these days, Wang Di woke to the ghost of a voice, a voice not unlike her aunt’s, calling out her name. As she lay in bed she remembered how her aunt once asked if Wang Di wanted to live with her; she could adopt her and take her away since her parents thought so little of girl children. She wouldn’t be like them, she told her, casting an eye at Wang Di’s father, but would make sure she went to school, got two sets of uniforms and books. An education.

“What do you think, Wang Di?” She’d smiled, a hopeful, shuddering smile.

Each time she remembered this, Wang Di wondered how her life would have been different had she said yes (in her mind her parents would have said go, good riddance), if she had gone to live with her aunt on the other end of Singapore, ten miles south in Chinatown, with its narrow alleys and smoky shophouses. Or if she had grown up and been approached by the matchmaker at the right time, and the war hadn’t torn through the island as it had: in the manner of an enraged sea, one wave after another sweeping everything away.

What she remembered most though, what she liked best, was the way it felt to hear her name, softly spoken.

Because the only time her parents used her name was when someone important was at the door, someone life-changing, or rich. The matchmaker was both. Auntie Tin had appeared at the door one Sunday and snaked inside past her mother before she had been invited to. A few months later, war would arrive on the island. Auntie Tin visited a second time during the occupation and then again—the third and last time—after the war, when Wang Di had little choice but to say yes. She had been the one to tell Wang Di what the words in her name meant and she had been the one who plucked her away from her anguished parents, away from the stolid silence of their home four years after they first met.

When Wang Di sat up and opened her eyes, the faint hum of her name was still in her ears, a song she couldn’t stop hearing. Her hand fluttered to the faint scar on her neck, right where her pulse lay, then went down to the line on her lower stomach, the raised welt of it smooth beneath her fingers. Eyes closed, she already knew what kind of day this was going to be—dread was pooling in her chest but she put her legs over the side of the bed and stood. Shuffled the narrow path to the altar. Eleven steps and she was there, lighting up joss sticks for everyone she remembered, saying, “Here I am, here I am,” as if they’d been the ones calling out for her: the Old One, of course; her parents, her aunt, and her two friends, one who died earlier than everyone else, and the other, whom she hoped was still alive. She was walking away from the altar when she turned back and lit up three more, planting them in among the fallen ash. Then she clicked the radio on before the memory of a child’s face, a memory as clear and smooth as a polished stone, could wash over her.

“Breakfast, Old One,” she said. Out of habit. Muscle memory. Her mouth hanging open in the quiet after her words. She knew there was going to be no answer and why, instead of the brown damp of newspapers, she was now surrounded by the scent of clay. Brick. A new house smell that made her feel sorry for having woken up. It was still dark out when she walked into her (new) kitchen and saw herself in the (new) windows: an old lady with a curved upper back that made her look more and more like a human question mark, and gray and white hair cut mid-neck—a style the kindly neighborhood hairdresser called a “bop.”

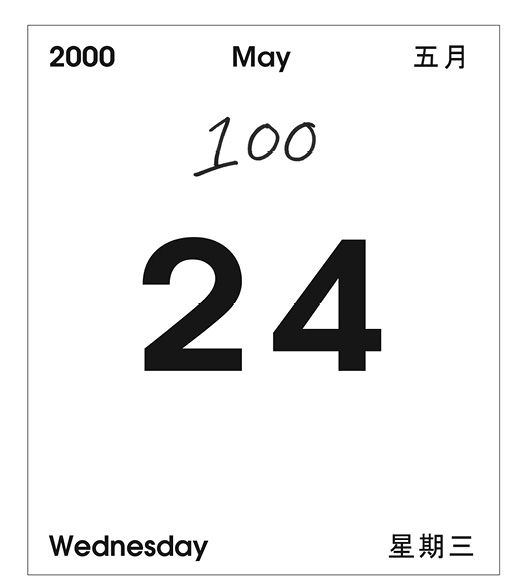

As the water boiled, Wang Di ripped off yesterday’s date on the tearaway calendar in the kitchen.

There it was: May 24. To make sure she wouldn’t forget, she had written 100 above the date. One hundred, as in “It’s been one hundred days since my husband passed away.” One hundred days spent regretting the fact that she hadn’t said and done all she could for him. She touched the black square of cloth on her sleeve—the black badge that told everyone that she had just lost someone close; the black badge that she wore even in bed on the arm of her blouse—and unpinned it. She fixed her eyes on the calendar again, for so long that the print started to squirm. Like ants on the march. Weaving left and right. The way her mind did these days, moving from past to present, mixing everything up in the process. She could be watching the news or doing the wash when everything blurred in front of her eyes and she would be reminded of something that happened years ago.

More and more, bits and pieces of her childhood came back to her, especially this: the many mornings she had watched as her mother stirred congee in a pot. Neither of them saying anything as she did what girl children were supposed to and laid out the cutlery. Five porcelain bowls. Five porcelain spoons. All chipped somewhere, the smooth glaze giving way to a roughness, like used sandpaper. Her mother would remind her to give the one perfect spoon to her youngest brother—Meng had a habit of biting down on cutlery as he ate from them. “He’s going to swallow a bit of china one day,” her mother used to say.

For the last hundred days, it was the Old One who came back to her. How she had left him that evening. The way he looked—she should have known, was trying not to think it while she combed his hair, telling herself how little he had changed. His hair was a little thinner, like a toothbrush that had lost some of its bristles. Thinner, and more white than black now, she thought as she combed it back. Lines around his eyes that stretched to his temples. She wanted to say it then, how he hadn’t changed much. Instead she said, “You look good today. Color in your face,” and wondered if he could tell she was lying, wondered if by saying it, she could will it into being. He smiled while she rubbed a damp cloth over his face, his neck, his hands, cracking his joints as she wiped from palm to nail. She saw how blue his fingertips were and knew it was a bad thing even though she didn’t know why.

Chia Soon Wei had said nothing as his wife fed him his evening meal and cleaned him. Every single word drew much-needed breath out of him, made his heart flutter and race. His voice used to ring through people, through walls, like a gong being struck. Now, it flitted out of him like a dark moth, barely visible. He nodded to thank her as she sat down and held the side bar on the bed, and wanted to start talking before she got up again to do something else, like pour another tumbler of water or tuck the sheet under his feet. Wanted to urge her to finish her story before it was too late, before both of them ran out of time. He knew what the unsaid did to people. Ate away at them from the inside. He had told Wang Di nothing. Not until a few years into their marriage, following a rare day at the beach. After that, all he wanted to do was talk about the war. What he had done. Not done. He’d brought it up one day at home, was beginning to tell Wang Di what happened during the invasion, but stopped when he saw that she was drawing back from him as he spoke, as if she were an animal, netted in the wild; and her face, how wide her eyes had become, how very still. The point was made even clearer when she woke that night, kicking and thrashing, cracking the dark with her cries. He had watched her until the sun came up, in case she had another nightmare, afraid that he might fall asleep and have his own. His usual, recurring one. One that he woke quietly from in the morning and carried around with him. One he had been carrying around with him for more than fifty years.

That day, at the hospital, he wanted to tell her that he understood, that it took time, gathering courage, finding the right words. But what a pity it was that they hadn’t started earlier. What came out instead was this: flutter flutter. A whisper that crumpled in the air half heard.

“What did you say, Old One?”

“I said you should finish your story. From yesterday.”

She nodded to mean yes, yes I really should, but her hands were shaking. She had told him everything. Everything but.

He beckoned to her. Closer. Come closer. Wang Di went to him, leaning toward his mouth.

“There’s nothing to be ashamed about. You did nothing—” he looked at her now, so fiercely that she had to force herself to hold his gaze “—nothing wrong.”

“I know. I know.” But she was shaking her head, her body betraying what she thought. What she wanted to say was, You might change your mind. You might change your mind after I tell you the rest of it. So she hemmed and hawed, then started talking about the various neighbors who had come over to say goodbye over the last few days, about the trash heaps that people were leaving behind, piled up along the corridor.

One of the last things she said to her husband was, “You should see the state of the building! Rubbish everywhere—old textbooks, a mini fridge—as if it doesn’t matter anymore, now that the building is going to be demolished.”

This was another thing she regretted. How she had rattled on instead of asking him if there was anything he wanted to tell her, to unburden himself of. And this one question in particular: where he had been every 12th of February (until his legs started to fail him) and who with. All questions that had looped over and over in her head the first time he had left and come back again at the end of the day. All questions that she’d practiced saying out loud every year after that while he was gone. That she pushed away the moment he returned home. And all because of that little voice, not unlike her mother’s, which hissed at her, warning that he might want answers of his own, out of her.

And then what would happen? Would she stay silent? Would she lie?

This is how it became their part of their life. Wang Di turning away when he said he would be gone for the entire day. How she would say goodbye to him over her shoulder as if it meant nothing to her; how she laid out the dinner things in silence when he arrived home later that day smelling of smoke and dirt and sweat. All of this, they repeated. A play of sorts, an act, that they would repeat year after year for half a century.

Even then, at the last, she let it lie. A sore point left untouched for so long that it would be too painful, too ludicrous to bring up at the eleventh hour.

She skirted the topic. Started complaining about other people’s trash.

At eight that evening the nurse came in, and in the quiet way of hers, signaled the end of visiting hours. A tap of her white orthopedic shoes on the floor. A low cough. Wang Di stood. She and her husband had never hugged in public. Not once in fifty-four years. Instead she gripped his hands, then his feet on the way out. Cold. As if he were dying from the bottom up.

The old lady batted away the thought by waving her hand. “Bye-bye, I’ll see you tomorrow.” Her words sounded strange, like an off-key note in an orchestra, but she kept smiling. Nodding. Squeezing his foot.

He waved without lifting his elbow off the bed.

Wang Di waved back, turned the corner and left.

The next day, she had woken with the resolve to try harder, reminded herself not to hold back later on. She had made him his favorite soup, pork with pickled cabbage and peppercorns, and she left it to warm in the slow cooker while she did the day’s collection. Returned home when it got too humid, the heat like a hot damp blanket around her body, and opened the front door to the salty perfume of bone broth. It was almost noon when she arrived at the hospital with the sense of something gone wrong. If she could she would have run. For a moment, when she got to his ward and found him gone, she half expected a nurse to come and touch her arm and say that he was just in the shower, he was strong enough now. Or that he had been wheeled away for an X-ray or scan. But no. She was there for a few minutes, the red thermos like a weight in her arm before anyone took notice of her.

The bed had already been stripped. What they would never tell her was the way he had died. How his heart had stopped beating and the doctor on duty and two nurses had hurried in. How the young doctor had leaped on top of the bed, knees on either side of the patient, and started doing chest compressions. How, finally, the head nurse—the same one who went into the ward to tell Wang Di that her husband had passed away—had laid a hand on the doctor’s arm to get him to stop. He climbed off the bed, straightened his clothes, and looked at his watch, noting the time of death—10:18.

“We called you at home but there was no answer.” The image of the doctor and Mr. Chia, dead or dying, bounding up from the mattress again and again from the force of each compression, was still playing behind the nurse’s eyes. On and off and on, like a film projector on the blink. She pinched the top of her nose to make it go away. “He went peacefully...like falling asleep,” she said, her voice cracking at the effort of the small, merciful lie, her cloying words. Like talking to a child. When in fact what happened was the man’s heart had failed. He had been lucky the first time. Not the second.

Wang Di couldn’t fathom the possibility that the Old One was dead, couldn’t even begin to think about it, so she started apologizing to the nurse instead. “I’m sorry. You called? I’m sorry I was out.” She had been picking up cardboard and newspapers, getting her collection weighed at the recycling truck when the Old One had died. $9.10. That was how much she had been paid that morning. She tried to recall how it had come to this, how quickly it had happened—in little more than a month. First a cold. Then this. How could a cold kill you? she thought, reaching forward to put a hand on the bed. The sheets on it were cool, fresh from a cupboard. It was then, while the nurse was giving her the pale, sanitized version of what had happened, telling her that his death had something to do with his age and an infection and his heart—that the words I should have asked him, I should have asked him, thrummed in Wang Di’s head. So that when the nurse asked if there was anyone they could call for her, perhaps a child or another family member, all Wang Di could say was, “I don’t know. I don’t know anything about my husband.”

Afterward, she had sat in a white-walled room as they brought her papers to sign. When she told them she couldn’t write (or read), someone ran out for an ink pad and helped her press her thumb into it, as if she hadn’t done it before, couldn’t manage it herself. And the way they kept saying his name. “Chia Soon Wei,” over and over again, she forgot why, could only think about the fact that she had never called him Soon Wei. Not once. It was a week after the wedding ceremony before she could look him full in the face. A whole month before she started to call him Old One, a joke (another first with her new husband) because he was eighteen years her senior.

At his wake, the guests—mostly neighbors—kept saying the same thing to her: “Uncle Chia had a long life.”

Each time, she had nodded and replied, “Ninety-three,” as if to reassure them and herself that they were right, that ninety-three was good enough. It made her wonder how long she might last after him. Later on, lying alone in the dark after his cremation, she had decided that ninety-three was nothing at all. He had promised more.

A month after that, she had moved from Block 204 to this apartment. As was planned before the Old One’s death. Everything went on the way things did after someone died. The housing officer came by to give her three sets of keys. The volunteers at the community center packed everything up and installed her in the new place. While all this was happening, Wang Di spoke and walked and slept with a Soon Wei-sized absence right next to her. The illogicality of it. Both of them were supposed to move to the new place. Just as both of them had looked at the buildings offered by the housing board and picked out the one closest to the home they’d lived in for forty years. The housing agent had rolled out a map of Singapore—a shape that always reminded Wang Di of the meat of an oyster—and drew dots to show them where the buildings were. “Here,” he’d said, “here’s where you live now.” He drew a red dot. “And there, there, there—those are the buildings that are available.” Three more red dots. They chose the one closest by, a thumb’s length away on the map. It turned out to be thirty minutes away on foot. It might as well have been another country, another continent.

Moving had meant losing him again. Losing everything: the neighbors with whom he would play chess for two hours every evening before coming back up to help with dinner. The stall from which he would buy a single packet of chicken rice every Sunday afternoon, him taking most of the gizzard, her taking most of the tender, white meat. The medicine hall’s musty waiting room where she’d sat, staring at illustrated charts pointing to body parts both inside and out, while the sinseh took his pulse and stuck needles into him. Each of these things, person, each place, holding a part of her husband like an old shirt that still retained the smell of his skin.

After the movers left, she had busied herself unpacking, opening box after box until she tore open the one filled with Soon Wei’s belongings. She had disposed of nothing, given nothing away even at the volunteers’ quiet urging. There they were: his walking cane, four shirts, three pairs of trousers, and two pairs of shoes. His sewing kit. A plain wooden box containing his Chinese chess pieces, the words on top worn smooth from touch. A biscuit tin packed with newspaper clippings and letters. She had sat down then, on top of the box, and wept.

The box was now next to the bed. The surface of it clean, bare except for an alarm clock. Once a week, Wang Di peeled back one cardboard flap so she could inhale the scent of his clothes and papers, then shut it again, as if the memory of him could waft away if she left it open for too long. She looked at it now, her fingers furling and unfurling. No, too soon, she decided, then got up to open the front door. This was what she used to do—leave the front door open to let the neighbors know she was home—the gesture like a smile or a wave. But it seemed they spoke a different tongue here. Her new neighbors didn’t even leave their shoes outside because they thought they might get stolen. Since she had moved in, she had only exchanged a hello and goodbye with someone’s live-in domestic. Now and again she heard voices, soft and companionable, passing her door. The shuffle of well-worn soles. But they were gone before she could unstick her tongue from the roof of her mouth quickly enough to call out a greeting. She wondered if she might be able to do it again, hold a proper conversation. All she said nowadays was “Good morning, how much does this cost?” “Too much!” “Too little!” “Thank you.” Maybe she would be found one day wandering the streets, able to say little else. To make sure she wouldn’t end up like that, she sometimes repeated the news as she heard it on the radio, saying the words aloud, aware that the Old One might have said these words to her had he been alive—he liked to read the thick Sunday paper to her while they sat on a tree-shaded bench.

As she listened to the news radio that morning, she recited:

“Household-income. Grim view of bottom earners. Top percentile richer.”

“Schoolboys arrested for throwing water bombs.”

“National University of Singapore revamping its courses to produce more leaders for the country.”

“And now we have the hourly traffic updates. Major incident on the A.Y.E.”

A quarter of an hour later she had said all she was going to say for the rest of that day. She made coffee. Halved a mangosteen—his favorite fruit—and placed both halves in a bowl, white flesh facing up. A hundred days. At the altar, she stuck three joss sticks in the tin can and cleared her throat. The thought that she’d had months ago, at the hospital, blooming to the surface. I never let you talk. I should have let you. Here she paused, picturing how she had stopped him each time he brought up the war. How she froze, or left the room, or cried. How his need to talk about what happened during the war had given way to her fear of it, so that she was left now with the half history of a man she had known for most of her life. “I’m going to fix it. I am,” she said, a little below her breath. She wasn’t sure how. Not yet. But she would find out, had to find out, all that she could about what happened to him during those lost years. “I’m going to fix it,” she repeated. Here her voice gave, and she had to force herself to smile and change the subject. “I might need your help but you don’t mind, do you? Staying around?”

Because aside from Soon Wei’s photo on the altar, there was a stark absence of anything else that might hint at a wider family. An absence as real as a wall, so solid you would have to be blind to miss it. No cluster of toys for visiting grandchildren, no extra chairs around the kitchen table for large weekend dinners. Nothing on the walls except for the pages cut out of Zao Bao, the Chinese morning paper, and the English paper (which the Old One couldn’t read but had clipped out anyway for their accompanying photos). He had collected them for years, and the collection had grown over time into a patchwork of paper tacked up on the wall of their home. On the day of the move, she had made sure to remove the articles herself. One of the things she did that first evening in the new apartment was to put them up on the wall along the kitchen table, a fine approximation of where they had been before. There was one picture of Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew shaking hands with the Japanese prime minister, a short column of words right underneath it. Another was a photo of two women in traditional Korean dress; one of them held a handkerchief to her face, the other stared straight into the camera, lower jaw hard, daring the seer to blink.

The Old One had watched her face as she looked at the two Korean women. His voice was soft, cautious when he said, “People are still talking about it... People who remember what happened during the war.” And he had read the column aloud, which he did when there was something in the paper that he thought might interest her. She had listened and not said a word. The quiet afterward was so thick she felt that someone had wrapped a bale of wool around her head. Later that evening, when the Old One was taking a shower, she got up to peer at the woman whose face was half-obscured. That could be her—Jeomsun, she thought. Wang Di remembered how, decades ago, they had talked about her going to visit one day. Jeomsun had laughed and promised to take her on a long walk into the mountains; it was one of her favorite things to do. Wang Di had told her it would be her first time then, seeing a mountain, climbing one. There were no real mountains in Singapore, she’d told her, only hills. Jeomsun had said, “You know, it sounds strange but I feel the absence of it. Like I’ve lost a limb, or an ear, almost. You live in a strange country, little sister, the wet heat, the land all flat and small.” It was then that Wang Di realized how little her world was, how strange and cloistered everyone else must think of her place of birth—all the soldiers and tradesmen, the captives brought over by ship. A cramped little prison island.

The memory had landed like a hot slap across her face. She couldn’t stop hearing their voices—not just Jeomsun’s, Huay’s as well. After decades of muffling their voices in her head. Of trying not to see them when she closed her eyes at night.

Later that evening, she had asked. “Those women that you read about, who are protesting... Do they live in Korea?”

“Yes, yes. But there are others too. In China, Indonesia, the Philippines...” He had stopped there, nodding slowly. Eyes on her the entire time.

He had given her that same weighted nod earlier this year as he waited for her to speak. The week before he caught a cold. The cold that made him ill for close to a month before he toppled over with a heart attack. But even before all that, before the visits to the Western doctor who dispensed antibiotics like giving candy to children, before Wang Di’s long wait for the ambulance, which seemed to take the entire afternoon to arrive, before all that, he seemed to know it was coming. The approaching, ultimate silence. And he had behaved accordingly, Wang Di realized afterward, and insisted on having a Lunar New Year meal. A proper reunion dinner, not sitting in bed in front of the TV but at the table. She had returned home from collecting cardboard one afternoon to the smell of roast duck procured from Lai Chee Roast Chicken and Duck at the market. There was soup stock bubbling away in an electric steamboat on the table. And fish cake, raw stuffed okra, silky tofu, and straw mushrooms, all plated on the side, ready to be plunged into the boiling soup. Sweet tang yuan to round off the meal. Cutlery already in place. She had smiled and combed her hair while he scooped rice into two bowls. It had been years since they had shared a reunion dinner like that and they started off much too polite, sitting straight up in their chairs as if they were meeting for the first time. It took them a while to stop watching each other over the tops of their bowls and begin talking about their day. The sweet dumplings they ate to the sound of the eight o’clock news on the radio, settling back into their easy silence.

Later, she went to bed and found him sitting up with his eyes shut. Wang Di had to resist the urge to wake him—she had never liked watching him as he slept. His face was meant to be lively. He had dark, bristling eyebrows meant for wiggling above his eyes, a sturdy nose that he wrinkled as he worked. A mouth full of square teeth that he ate and grinned and tore off threads with. At rest now, it was as if he were only a fraction of himself. Wang Di could see what he might look like if he were never to move again.

So she put her hand on the top of his shoulder and shook. “Old One, are you awake?”

He flared his nostrils wide but said nothing, nor did he slide down into his usual sleeping position, flat on his back with one arm above his head. She sank into the mattress, close to his feet, trying to find the firmest spot in their sat-upon, laid-upon, age-old bed, and waited for him to speak.

“Tell me a story.”

It was then that she knew he had been waiting to say this. Waiting decades for the right moment. And now he couldn’t wait anymore. “What—what story?”

“Any story.”

She stayed silent for a while until he put his hand on hers; she had been tapping her nails on the bed frame without meaning to.

“Just talk about something from your childhood, where you went with your mother on market day, for example, what you saw there.”

The clock ticked its thin, plastic tick. Minutes passed. The first thing that came to her was this: “There used to be a man who sold his songs near the city.”

She stopped to look at him and he nodded slowly, telling her to go on. “He would be outside one of the coffee shops whenever it was not raining, sitting on a bamboo stool, a well-worn walking stick gripped in his left hand. His face looked like it was made of ragged sackcloth and he hardly moved while he waited for the right moment to begin. Then he sang. And the sound of feet around him hushed for their owners to hear better. The market with its stalls selling vegetables and home-grown poultry, the noodle stall with its sweaty cook pouring pork-based soup into bowls. The chatter of the market never stopped, but the sound of his voice, his songs about home, about missing the old country, about love and its ills, lulled everything around him into a different rhythm. Even the noodle man, with a cloth wrung around his neck to catch drops of sweat, could be seen using the same cloth to dab at his eyes whenever he thought no one was looking. People clustered around the old man, going close, listening with hands behind their backs or clasped at their chests and at the end of it, some of the people who had gathered around to listen threw coins into a tin mug.

“I always stood at the edge of the crowd, out of sight, peeping now and then to look at the expression on his face. It pained me that I had nothing to give him and I made myself walk away before the end so that he wouldn’t see me—never with a coin but always there, long after my vegetables and eggs were sold, listening.”

When she stopped, she could hear the last of her words clinging to the warm air in the room. He opened his eyes and nodded once more. Go on. She took a deep breath as if she were about to plunge her head into water, ignoring her mother’s voice in her head. What she had said to Wang Di the night before her wedding: “Remember. Don’t tell anyone what happened. No one. Especially not your husband.”

When Wang Di spoke again, it was about home. About the year it all began—her almost-marriage to someone else, her too-short childhood, the war. For a week, they sat like this in the night, in the dark, the Old One leaning toward the sound of her voice. This was how she started.