I’m in the control room, separated by a glass that goes into the studio, and she was sweating from working so hard at her performance, and there was one moment, you know, the glare of the glass, the light, you know it just looked like she was covered in rhinestones.

Singer Toni Wine

In 1961, her finances restored by her overseas tours, Rosetta again bought herself a home, in Yorktown, a federally financed North Philadelphia housing development specifically targeted at middle-class blacks. The house at 1102 Master Street that she and Russell (and Mother Morrison—Katie Bell was now in her own apartment) moved into was modest, but the fact that they were the original occupants made it special. Rosetta could look out her front window at a quiet, clean street as she cooked in a brand-new kitchen featuring a matchless stove, and she could entertain herself or guests by playing the small upright white piano in the living room. She and Russell furnished it nicely, says Roxie Moore, with Italian furniture, matching draperies, and a “great big round bed” in the bedroom. Some time in the mid-1960s, the picture of domestic comfort at 1102 Master was perfected by the addition of Chubby, Rosetta’s white poodle, whom she spoiled by feeding him table food and occasionally even taking him on tour with her. According to Donell Atkins, Rosetta’s half-brother, who visited from time to time, Chubby would bark at anyone except Rosetta. Annie Morrison, with sly wit, counts Chubby as among the many friends of Rosetta who had no love for her husband.

Rosetta and Russell saw a good deal of Ira Tucker and his family in the early ’60s, at least on those occasions when neither she nor the Dixie Hummingbirds were away on tour. She and Tucker loved nothing better than a day of fishing. When the weather was fine, they would rent a party boat to take them out for the day down in Cape May, New Jersey, or Kent Narrows in Maryland. “Yeah, she loved to fish, that’s the one thing she really loved, is fishing,” recalls the gospel singer Frances Steadman, a friend who also enjoyed going out with Rosetta.

Word had it that the singer of “Two Little Fishes” could outfish just about anyone, including Tucker, who considered himself pretty proficient. “Oh, she could fish,” Ira Junior says, recalling the way Rosetta would psych out even her most accomplished fishing buddies. “She’d fish and talk. You know, she’d be talking to you, talking all fast, and just catching ’em while she’s talking to you. And then laughing at you at the same time.” Just as she liked showing up men on guitar, being better on a “male” instrument than women were supposed to be, so she liked showing them up with a fishing rod and reel. “And my old man can fish, now!” exclaims Ira Junior. “He’s been known as a top fisherman, but Rosetta could put him to task.”

If there are two kinds of people in the world, those who enjoy fishing and those who can’t imagine a day worse spent then out on a boat, immobile, in the middle of a body of water, then Russell was the second kind. He liked staying ashore where he could protect his foreign investments—the suits and hats he had purchased in Paris. “Russell liked to eat what fish Rosetta caught, sure, but he couldn’t mess his hands up,” Ira Junior says. “Russell was like, No, baby, we’ll buy them.” He chuckles. “That’s the kind of guy he was. I loved him for that, though. I mean, he never allowed himself to get ruffled by anything. I mean even when his hair was turning grey and he had dyed it so much that he couldn’t dye it no more, and the grey was coming through, and he was saying, You know, I think, maybe I’ll need to go bald. I loved that. It was like, he could make up—he had a way of reinventing things.”

When she wasn’t fishing, Rosetta spent her downtime in those early years on Master Street with her girlfriends, including singers Marion Williams and Kitty Parham, Ward Singers alumnae who, along with Frances Steadman, had recently fled Gertrude Ward’s penny-pinching dominion to form their own Philadelphia-based group, the Stars of Faith. “At that time, everybody was singing, trying to make a dollar,” recalls Steadman—now Frances Steadman Turner—so it was a while before she discovered that she and Rosetta had become neighbors. When they finally did connect, it was through a chance meeting. “I saw her husband one day,” Frances recalls, “and I said, Whatcha doin’ in Philadelphia? and [Russell] said, Well, I live right around the corner! I said, Is Rosetta home? He said, Yeah, she’s home right now. So that started a little close friendship, you know.”

Once she settled into the neighborhood, Rosetta also joined Bright Hope Baptist, the Yorktown church that Frances attended. Because the pastor, Reverend William H. Gray Jr., was not merely a local leader but a former college president and an early comrade of Martin Luther King Jr., the church attracted a fair share of prominent and politically active congregants. Rosetta might have joined out of an awareness of herself as a public figure in North Philadelphia, says Ira Tucker Jr. Or, as Roxie Moore speculates, her switch to a Baptist church might have been a sign that the saints had finally worn her down after all those years. Some people in the Sanctified Church would turn their backs on a member for one little sin; even after twenty years of spotless living, that single transgression would never be forgiven.

Although she was not the national superstar she had been in past decades, Rosetta’s career was relatively prosperous in the early ’60s. She might have taken a bit of satisfaction in noticing that, more and more, gospel music seemed to be playing catch-up with her. Even some of the most stubbornly traditional performers had shifted course as gospel drew a greater share of the white commercial audience. Clara Ward took to playing club gigs, first with Thelonius Monk at the Village Vanguard, later in the sinner’s paradise of Las Vegas. “I was against it for years,” Ward explained to Jet magazine when word of her downtown jazz gigs got out. “I was brought up to believe night clubs were bad, wrong, immoral. I don’t see it that way now. I have long wanted to reach a larger public and I think I am doing it this way. I might help some of the club patrons spiritually, who knows?”1 Her reasoning echoed Rosetta’s on “We the People” twenty years earlier.

As the nightclub barrier continued to fall, so the early 1960s saw a rise in gospel’s visibility: through the continuing success of Ray Charles, hitting big at ABC-Paramount; the ongoing interest of folk revivalists; and the success of Langston Hughes’s play Black Nativity, which debuted on Broadway in late 1961. Against the backdrop of such developments, Rosetta channeled her considerable energy during this period into recording. Although they are generally not associated with her finest work, the late 1950s and early 1960s were the most prolific years of Rosetta’s career, measured in terms of sheer output. In the span of about thirty-six months between 1959 and 1962, she released a total of five long-playing albums: The Gospel Truth (Mercury), Spirituals in Rhythm (Omega), Sister Rosetta Tharpe (MGM), Sister on Tour (Verve), and The Gospel Truth (Verve). Together, they included an astonishing fifty-six songs, demonstrating her masterly command of the gospel repertoire, as well as the vitality of her singing and playing in a variety of musical contexts.

Sister on Tour and The Gospel Truth, the two albums on Verve, Norman Granz’s highly respected jazz label, were the most noteworthy. The first paired Rosetta with top-notch producer Teacho Wiltshire, the second with a young producer named Creed Taylor, who would later become famous for launching the global bossa nova craze with “The Girl from Ipanema.” “I didn’t pick any of the songs. Didn’t ask her anything,” Taylor recalls of their sessions. “We just talked, got acquainted with each other, and she came in and recorded. . . . I didn’t produce her, per se. I allowed her, I guess you might say, to sing her great stuff and I recorded it.”

The Gospel Truth was recorded at Webster Hall, a place with “a huge ceiling, like three or four stories high,” Taylor recalls. Rosetta got up on one side of the room, the side with a stage on it, where he thought she’d be more comfortable performing. “And we all had a ball recording it. She was dynamic, I just remember her guitar filling that whole large area with such great blues stuff, wow, gospel blues—whatever you want to call it. . . . She was a blues shouter just like Esther [Phillips]. . . . If you didn’t understand it, it’d be actually frightening. What’s all the excitement about, you know?”

Ella Mitchell, a member of the All-Stars, remembers how Rosetta took control of the Gospel Truth session, even as they recorded the album on the fly. “We came to the studio that day and recorded that day and finished it that day,” she says. “We took ’em one at a time.” At one point, the All-Stars and Rosetta were rehearsing “I Looked Down the Line,” when Rosetta said, “C’mon whatcha gonna do behind that?” “And I said we just should sing ‘Wondered, wondered,’ ” Mitchell recalls, singing. “And she said, That’s it, that’s it right there! Don’t go no further. And then she’d holler in the air [to the engineers] ‘Y’all got that? Y’all got that? These girls was bad, y’all got that? These girls was bad.’ C’mon let’s show em up one more time. . . . She made sure that you understood exactly what she wanted, like she said, and the moment she explained it and showed you, then she’d make a joke of it, in other words she would make it fun. And that’s the key, she would make it fun.”

Rosetta wasn’t the only one pursuing multiple musical projects in the early 1960s. Mother Bell was busy, too. For one thing, she had her usual work of saving souls to attend to. Ira Tucker Jr., then a teenager, remembers helping Miss Katie tote her guitar and her amplifier to Speedy’s bar at Fifteenth and Columbia Avenue in Philadelphia to play until she won a new soul for Jesus. “She wouldn’t quit until she did,” she recalls. “No, she was there for real. She wasn’t there to play, she was there to do damage. I mean, she set up in front of a bar. That’s what I liked about Miss Katie, she set up in front of a bar! . . . And she would hit ’em from, like, twelve o’clock until it got dark.”

“My mother, Katie Bell Nubin, sang in the local church choir and gave me a thoroughly religious education from the musical and all other points of view,” Rosetta told an English journalist in 1957, on the eve of her first European tour, “but it was she who encouraged me more than anyone to regard jazz and the blues as healthy music rather than a sinful pastime as some preachers would have us believe.”2 Rosetta may have been rewriting history a bit, and yet on New Year’s Day, 1960, Katie Bell, then in her midseventies, would make good on such beliefs, recording her first and only LP in collaboration with their old New York friend Dizzy Gillespie. The pairing of the gospel matron and the spiffy bebop innovator was surely anomalous—jazz critic Martin Williams tactfully referred to their “appropriate but unusual alliance”3—but the album, a collection of traditional and contemporary material set to arrangements that evoke the connectedness of gospel and blues, worked out surprisingly well, if only because the younger musicians respectfully let Miss Katie do her thing.

“We just followed her,” recalls bassist Art Davis, “because Dizzy had respect for her and didn’t want to tell her what to do and just let her go. . . . She sounded, and then Dizzy took some solos, some jazz solos, on her, and we did some background while she played and sang, and then let us do our instrumentals.” Junior Mance, then a relative newcomer to Gillespie’s band, recalls that, before the Soul, Soul Searching session, he knew nothing about Katie Bell Nubin—not even that she was the mother of Rosetta Tharpe, the gospel singer whose records his mother used to play around the house when he was a boy. But he was impressed by what she could do: “She had a strong conviction in the voice. She just came right out and sang.”

On August 29, 1963, Marion Williams celebrated her birthday with a party at her Philadelphia home. The day before, Martin Luther King Jr. had led the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. No one at the party had attended the march, but everyone had watched it on television, along with the rest of the nation, recalls Tony Heilbut. They discussed King’s famous speech, but in particular, the crowd of gospel singers talked about Mahalia Jackson’s performance of “I’ve Been ’Buked and I’ve Been Scorned.” Jackson’s alliance with King and the movement was well known, but it was another thing to see her on TV, boldly singing the song King himself had requested.

Rosetta never had Mahalia’s political cachet or her connection to the civil rights movement. Earlier that summer, she had appeared at the Newport Folk Festival, but she remained at best marginal to the folk scene, whose core audiences preferred the music of pioneering freedom singers like Odetta, a proud black woman who wore her hair in a “natural”—unlike Rosetta, who wore her hair in a mortifyingly out-of-date pressed and dyed style. At Newport, moreover, where the acoustic guitar was considered authentic, Rosetta’s new solid-body white Gibson SG custom electric instrument, said to have set her back $750, lost its significance as a symbol of her modernity and polish.

In England, on the other hand, Rosetta’s music was attracting a new cohort of fans. As early as 1957, Rosetta had told London’s Daily Mirror, “All this new stuff they call rock ’n’ roll, why, I’ve been playing that for years now.”4 Now, toting a glossy instrument with impressive-looking stainless steel hardware, she was making good on that claim. If there was anyone to contradict her, it was not Marie. “Rock and roll actually started from the church, because it’s [about] time, and music is time,” she says. “If there is no time and no beat, there is no sound. Ninety percent of rock-and-roll artists came out of the church, their foundation is the church. . . . All the way back as far as you can go back, rock-and-roll artists started in the church.” In England, Rosetta’s instrument announced her status as “rock.” “I was there at the beginning,” it said, “and I’m still here. Just watch what I can do.”

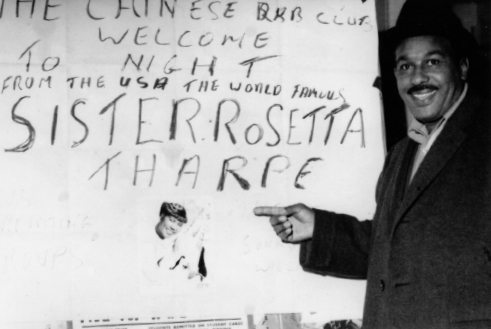

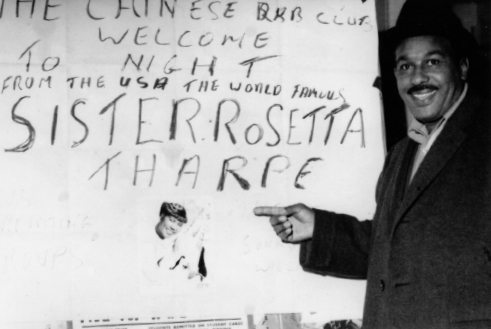

Russell Morrison points to a sign advertising a show by “The World Famous Sister Rosetta Tharpe” at the Chinese Rhythm and Blues Club, Bristol, England, November 1964.

From the collection of Mrs. Annie Morrison.

For the floppy-haired English youth who enthusiastically greeted Rosetta at her solo gig at Bristol’s Chinese Rhythm and Blues Club in November 1964—a day after Martha and the Vandellas arrived in London to promote their single “Dancing in the Street”—the attraction was precisely those aspects of her persona and her music that had befuddled the revivalists only a few years earlier. No longer was the loudness of her guitar something to be painfully endured; now it was a celebration of musical energy, its ability to take listeners “higher.” The metaphor of elevation came directly from the church, where prayer and faith had the power to lift you up, but by 1964, getting “higher” also referred to the increasingly widespread practice of using drugs to experience something akin to religious ecstasy.

Virtually all of Britain’s young Turks of rhythm and blues honed their craft by studying the musical licks and tricks of the group of African American “roots” musicians who toured Europe in the 1960s. The Spencer Davis Group, the Yardbirds (featuring eighteen-year-old Eric Clapton), the Animals—all of these groups based their earliest music on 12-bar blues, and many scored their first hits covering songs either by their heroes of the blues revival or by contemporary rock and rollers. Sometimes the material they covered was preposterously remote (Mick Jagger, for example, singing about driving down the New Jersey Turnpike at dawn, in a remake of Chuck Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me”), but as expressions of feeling, such songs also made a strange and profoundly compelling sense to an English lad from Kent. Once bitten by the blues bug, moreover, most found there was no turning back. Even the Beatles, known for having an accessible pop sound that contrasted with the “blacker” sounds of the rhythm-and-blues purists, bore traces of the revival in their music. Listen to the opening bars of “Love Me Do,” and you can hear the revivalists being channeled in John Lennon’s youthful attempts at blues harmonica.

No other American woman was as central to the transatlantic flow of sound that we know today as the British Invasion as Sister Rosetta Tharpe. A woman among men and a gospel musician among secular blues players, she was still somewhat sidelined as an anomaly. Paradoxically, however, the very qualities that had always rendered Rosetta an outsider—her flamboyance, her over-the-top style, her association with the guitar, her need to differentiate herself from other Pentecostals through unconventional choices and outrageous behavior—rendered her irresistibly compelling to the British blues-rockers of the 1960s. “We had heard the original rock ’n’ roll—Buddy Holly, Elvis and Gene Vincent, Little Richard, the Everly Brothers and Chuck Berry,” said Moody Blues drummer Graeme Edge in 1992. “We put all of that together, and at the same time, discovered another 30 years of American experience on record—Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee [sic], Sister Rosetta Tharpe and all of those people. Then we repackaged it and sold it back in a very free approach.”5

Young British rhythm-and-blues fans acquired regular access to their American musical heroes through music festivals that toured Western Europe. The most famous of these were the annual American Folk Blues festivals, initiated in 1962 by a pair of German promoter-aficionados intent on educating a curious public about black American music. In preferring aging male guitarists and harmonica players to younger players, pianists, and women, the festivals cemented the quintessential image of the blues musician as a hard-bitten male troubadour. And yet they also provided an important outlet for a variety of sounds—including New Orleans jazz, Chicago electric blues, and country blues—at a time when such music wasn’t getting much of a hearing in the United States.

In the spring of 1964, Rosetta toured Britain as part of the American Folk, Blues, and Gospel Caravan organized by George Wein, the American promoter behind the Newport folk and jazz festivals. The lineup included Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Chess Records house pianist Otis Spann, the ever-popular Muddy Waters, New Orleans pianist Cousin Joe, and the country gospel musician “Blind” Gary Davis; although not featured performers, drummer Little Willie Smith and bassist Ransom Knowling rounded out the roster. Mississippi John Hurt, a hero of the 1963 Folk Festival, was originally scheduled to appear, but had to withdraw at the eleventh hour because of illness; so, too, did Lightnin’ Hopkins, rumored to have an aversion to airplanes.6

To manage the package, Wein hired Joe Boyd, a recent white Harvard graduate. Boyd had a bit of promoting experience under his belt, but nothing to prepare him for the challenges of a packed two-week tour of Britain with artists who—far from a fulfilling the myth of a blues community rooted in the “black soul”—not infrequently found it hard to get along. Brownie and Sonny, despite having been a team for years, disliked each other in the manner of an old married couple bitterly resigned to mutual dependency. And then there was Rosetta, who arrived in England with Russell—an exception to the “no managers” rule—and a chip on her shoulder. “I think when she arrived, she felt like she was a glamorous show-business star and that she was kind of slumming it with these funky blues guys who didn’t dress as sharp as she did, and some of them were pretty country, as far as she was concerned,” recalls Boyd. In particular, Rosetta was cool to the Reverend Gary—a surprise to Boyd, who assumed they would have lots in common. Eventually, after listening to Rosetta’s stories “about Katie Bell, about growing up in Arkansas, and about working the little churches in the rural Pentecostal circuit,” Boyd came to suspect that the roots of Rosetta’s dislike were deep. “She depicted [her childhood] as very hard,” he recalls, “and that was sort of how I interpreted her aversion to Gary—as being the kind of thing she escaped.”

The American Folk, Blues, and Gospel Caravan debuted on April 29 in Bristol, before a large auditorium overflowing with excited teenagers. “Here were these guys who could barely fill a 150-seat coffeehouse in America, and there the hall, with nearly 2,000 seats, was packed,” recalls Boyd. “I think at first everybody was kind of amazed that it was full and that there were kids queuing up for autographs.” That’s when Rosetta’s defensiveness melted away, he says. “It was a combination of being impressed with how big the tour was from the kind of audience point of view and also being really impressed with the musicianship of everybody else on the tour.”

One of the fans at the Caravan’s Sheffield show was Phil Watson, a teenager who had discovered Rosetta’s music a couple of years earlier, although he tended to prefer the rawer sounds of Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Blind Willie McTell. He came away from the Caravan impressed by Rosetta’s glittery sophistication, however. “Her showmanship and ‘front’ was in such contrast to the rest of the cast, except maybe Sonny and Brownie who, by 1964, had developed a polished act,” he recalls. “She was immaculately dressed and her hair—wig?—was beautiful. Her guitar playing was a revelation, and the electric guitar highly polished and she used it as a mirror to flash lights around the audience. She had a very nice stage patter and was clearly a very polished and sophisticated stage performer, unlike many of the others on the tour.”

John Broven, then a young blues enthusiast who craved the electric Chicago blues of Muddy Waters’s records on the Chess label, remembers his initial disappointment at the Caravan show he caught in London at the New Victoria Theatre. “I was looking forward most of all to seeing Muddy Waters and his pianist Otis Spann perform,” he recalls, but “incredibly they proved to be rather perfunctory, even with the backing of Ransom Knowling on upright bass and Little Willie Smith on drums. . . . Muddy was presented in a plodding folk blues format; this was how the Europeans wanted their blues—or it was thought. . . . The show did not spark until an exuberant Sister Rosetta Tharpe came on stage. A gospel act rocking? It was a total surprise. And a lady with an electric guitar, too!”

A couple of nights before the last Caravan performance, the musicians filmed a truncated version of the show for English television. Dubbed The Blues and Gospel Train, it was set at a defunct suburban Manchester railroad station turned into “Chorltonville,” a half-Hollywood, half-Disneyland fantasy of a Deep South rural rail depot. On one side of the tracks stood bleachers to hold about five hundred young fans; on the other side were hokey props, including a bale of hay (for Sonny Terry to sit on as he played), a rocking chair, two goats tethered to a rail, a “Wanted” poster advertising “$2,250 Reward for the Recapture of Robbers Connected with the Train Robbery,” and a sign advertising “Green Mountain Vegetable Ointment . . . It Cures Any Ailment.”

Had the special been filmed “the first couple of days of the tour,” Boyd speculates, Rosetta “would have freaked out.” After all, she had played run-down auditoriums, small churches, and theaters on the chitlin’ circuit, but never a train depot; back in the States, she didn’t even travel by train. But coming toward the end of the run, she and the other performers were in good spirits, despite a cloudburst just as the “Blues and Gospel Train”—a refurbished British Railways car decked out with a cowcatcher and a “Hallelujah” plaque—rumbled into the station. Brownie and Sonny opened the show, followed by Cousin Joe, who did “Chicken à la Blues” on a baby grand piano decorated with a cage of live chickens. By the time Cousin Joe introduced Rosetta, who was to close the first set, the rain was audible. “Ladies and Gentleman,” he announced, “at this time I take great pleasure in bringing to you one of the greatest, one of the world’s greatest, gospel singers and guitar virtuosos, the inimitable Sister Rosetta Tharpe!”

It was a genuinely generous introduction, and Rosetta acknowledged it by taking Cousin Joe’s arm, held out in gentlemanly fashion, as she descended from a horse-drawn surrey driven onto the Chorltonville platform by a man in livery. “Oh, the sweet horsey, oh the sweet horsey,” she cooed, trying to make the descent on high heels. In a sign that she had mastered the basics of British humor, she cracked a joke about the weather. “This is the wonderfulest time in my life,” she pronounced, as the rain poured down. Then she strapped on her white electric guitar and gamely played “Didn’t It Rain,” making use of the instrument’s considerable vibrato and attacking the solo bridge tastefully, without extraneous moves. As Cousin Joe looked on from the comfort of the rocking chair, she moved next into “Trouble in Mind,” taking the luxury of two guitar solos—one in which she ripped it up with a devilish laugh, another in which she made the instrument talk in a fanciful tone, while she stepped about the platform with delicate grace. “Pretty good for a woman, ain’t it?” she called out to the crowd, but no one dared to respond, understanding that it was pretty good for a man, too.

The television special concluded with Rosetta returning to the platform to lead the entire cast in a version of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” By that point, damp and exhausted, the Caravan players seemed genuinely at ease. Cousin Joe rocked contentedly in the chair, and Muddy Waters looked positively beatific. Plus, Rosetta had finally made her peace with Gary Davis. “By the end,” recalled Joe Boyd in an interview with Robert Gordon, “Rosetta had done a 180-degree turn on Gary and decided he was the deepest man she had ever met.” Two nights later, during their last British show, Boyd continued, “she told me, ‘When he does “Precious Lord,” get me a microphone off stage.’ He starts into this incredible version and Rosetta is on her knees backstage moaning right straight out of Arkansas, like she sang with her mother. Gary heard the voice and said, ‘Sing it, Rosetta.’ It was just incredible.”7

Had George Wein and Joe Boyd had their wishes, the American Folk, Blues, and Gospel Caravan would have had a future on American college and university campuses. But although the English had loved it and the French had gone into raptures over a special May 12 Paris concert, the organizations that controlled the U.S. campus circuits weren’t buying into it. The following winter, Boyd says, he attended a conference of performing arts presenters, but “I couldn’t get anybody interested, I mean in 1964, nobody was interested in this stuff in America.” The American Folk, Blues, and Gospel Caravan had only one American stop: at Hunter College on Sixty-ninth Street in New York City.

Around that same time, Rosetta and her white Gibson SG made two appearances as guest host on TV Gospel Time, a short-lived Sunday-morning variety show that aired on NBC beginning in late 1962.8 The brainchild of a Chicago-based producer, Harold A. Schwartz, TV Gospel Time created opportunities for nonprofessional gospel musicians to appear on television alongside national stars, and it pioneered the practice of bringing the production crew and featured guests on location, so that large choirs around the country could appear without facing daunting travel expenses. “Practically all the gospel stars at that time appeared on that show,” recalls Georgia Louis, who began working for TV Gospel Time soon after someone noticed her singing in a Stamford, Connecticut, paper-novelty factory where she was making Christmas bells. Louis, Marie Knight, Mahalia Jackson, Ernestine Washington, James Cleveland, and Jesse Farley, an original member of the Soul Stirrers, all filled the host slot of TV Gospel Time in its prime.

TV Gospel Time was the nation’s first series to use “all-Negro” talent exclusively, from singers and musicians to models and announcers. Yet some black middle-class viewers complained that a gospel show merely reinforced old stereotypes about black people as naturally religious. “The reaction of most college-bred Negroes in New York and Washington,” reported Sepia, “was one of dismay that a company”—in this case, the white-owned Feen-a-Mint, one of the show’s sponsors—“should select gospel music as a vehicle to show Negroes. To the white firm it seemed like the best idea since it is the Negroes’ aboriginal music and America’s only real folk music. But Negroes were not buying it in the North. However, the show, still on the air, has gone on to attract many listeners, many of whom are turning out to be white.”9

Such comments reflected the different cultural-political stakes of the image of gospel music in the mid-1960s in the United States and Europe. The overseas audience for gospel was considerable; Black Nativity had done fine on Broadway, but in its traveling European tour it was an all-out smash. In Europe, as well, gospel played to the liberal sympathies of jazz and blues fans. But in the context of U.S. civil rights, sensitivity about images of robe-attired, obedient, church-going “Negroes,” who put their faith in God rather than the ballot box, discomfited some viewers, including those who still recalled the mixed message sent by even well-intentioned representations of gospel, such as the 1936 film The Green Pastures.

Rosetta was pleased, however, to be asked to host not one but two episodes of TV Gospel Time. The first featured soloist Delois Barrett, the St. Timothy’s Gospel Chorus, and the Five Blind Boys of Alabama; the second, singer J. Roberts Bradley, the Imperials, and the Mount Olivet Institutional Baptist Church Choir. On the episode with the Blind Boys, Rosetta performed “Down by the Riverside” as her finale, taking the stage in a full-length flowered gown and blond hair, doing a “walk-about” move that dated from her late-1940s shows with the Dixie Hummingbirds. “You know the guy that goes down?” asks Ira Tucker. “Yeah, Chuck Berry got a lot of that stuff from her. . . . See, she would turn this way where you couldn’t see,” he says, motioning with his body. “She wore dresses, and she would turn this way where, you know, she’d be safe, you know. She wouldn’t turn where you could see in. . . . Oh yeah, she turned sideways to do that duck thing. But she didn’t go down quite as low as Chuck.”

Rosetta and her friend Madame Ernestine Washington join Mahalia Jackson for an interview on a gospel radio program hosted by Thurman Ruth on station WOV in New York, in the mid-1960s.

Mahalia was the only one scheduled to appear; Rosetta and Ernestine stopped by to say hello. Photograph by Lloyd W. Yearwood.

“She would make that guitar ring! I never saw a woman play guitar like that before or since,” recalls J. Roberts Bradley, a classically trained singer who remembers that once, as publicity for an upcoming Memphis show, Rosetta had herself driven around town, playing and singing, on the back of a pickup truck. Georgia Louis recalls an instance, however, when even Rosetta’s considerable gutsiness couldn’t spare her embarrassment. During the filming of one episode, she says, Rosetta kept flubbing the plug for Feen-a-Mint. For one reason or another, she kept cheerfully urging the people at home to try “the little brown pill”—not “the little white pill”—as the recommended remedy for constipation. Rosetta had to repeat the pitch three or four times before she got it right. The queen of gospel guitar pushing laxatives on Sunday morning television, and messing the words up! Georgia Louis still chuckles at that one.

Rosetta made her living through the end of the 1960s doing programs at home, as well as touring the European and American festival circuit, which remained strong even as the British blues revival began to ebb. In addition to appearing at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1964, on a program that reunited her with Count Basie, she performed at the First Annual Copenhagen Jazz Festival (1964); the Folk Blues and Gospel Song Festival, sponsored by the Hot Club de France (1966); the 1967 Newport Folk Festival, where she played piano while Katie Bell sang until she practically had to be pulled off the stage; and the 1970 American Folk Blues Festival. In each venue, she remained supremely confident; of Newport in 1967, she told Tony Heilbut, “I showed those children how you can play anything in gospel: blues, jazz, country and hillbilly.”10 While she was abroad, she did solo tours of anywhere from two days to two weeks—in France, Germany, Scandinavia, Spain, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Great Britain. After a several-years’ absence from the studio following her two Verve recordings, she also released three albums: Live in Paris, 1964; Live at the Hot Club de France (recorded in 1966); and Famous Negro Spirituals and Gospel Songs (recorded in late November 1966, but probably not released until late 1967 or 1968). The latter, the sole studio album she made abroad, found her working with Willy Leiser and a Swiss quartet, the White Gospel Four, a group that had learned to sing by copying what it heard on records by Mahalia Jackson and the Golden Gates. Hughes Panassié, Rosetta’s friend and the influential president of the French Hot Club, dubbed the Four the “weak point” of the LP, and yet nothing could shake his faith in Rosetta’s talents: “More than ever after having listened to this record,” he wrote in April 1968, “I think that Rosetta Tharpe is one of the greatest, most moving artists of our time.”11

At the time, Mother Bell, then in her mideighties, was living in the house on Master Street, where she passed her time tending the small garden out front and playing her mandolin or the piano. “She lived for singing and Jesus,” wrote Tony Heilbut; “if you asked her about speaking in tongues, she’d tell you ‘Lord, yes. The Holy Ghost, that’s my company-keeper.’ ”12 One day, however, she called Rosetta aside and told her she was feeling cold, and that she heard music “like Count Basie’s playing in the next room.” Rosetta reassured her, “Oh, you poor thing, that’s just the angels getting you ready.” Soon after, Rosetta’s premonition came true: Mother Bell had her stroke.13

Two weeks later, Louise Tucker and Roxie Moore, Rosetta’s closest Philadelphia friends, came to visit Mother Bell at St. Luke’s Hospital, where she lay dying. “We were standing by her bedside,” remembers Roxie:

Louise had one hand on one side of the bed and I had the other hand on the other side of the bed. And we were talking with her even though she was like in a coma, but she would blink her eyes and we would ask her, you know, to do something, or to squeeze our hand if she understood what we were saying. And she would do both. And we stood there and we promised her not to worry, that we would take care of Sister for her and that we would be just like Rosetta’s sisters, and that she didn’t have to worry—she could go on home to be with the Lord, you know, rather than lay there and suffer. And I think it was just that night or the next day that she passed.

Few relatives attended the funeral at the William H. Brown Funeral Home on Girard Avenue; Mother Bell, apparently, had outlived most of her contemporaries. However, two church dignitaries showed up to pay their respects: Bishop O. T. Jones, senior bishop of the Philadelphia Church of God in Christ, and Bishop O. M. Kelly of New York. Ernestine Washington made the trip down from Brooklyn, and the three women—Ernestine, Louise, and Roxie—sat together with Rosetta and Russell during the service. The Reverend Robert Cherry of Washington, D.C., preached the sermon, Roxie read the eulogy, and both Ernestine and Marion Williams sang, Marion doing Mother Bell’s song “Ninety-nine and a Half Won’t Do,” until, as Rosetta later recalled, “the folks hollered and carried on like we had revival.”14 After the ceremony, Mother Bell was laid to rest in Merion Memorial Park in the Main Line Philadelphia suburb of Darby. Roxie Moore made sure to send a photograph and an obituary to the Philadelphia Tribune, so that Mother Bell’s passing would be properly noted.15 It was, in a banner headline that ran above the masthead on page one.

Katie Bell had been by Rosetta’s side—as mother, collaborator, protector, friend—for so many years that the loss, for all that she anticipated it, must have cut especially deep. Tony Heilbut, who saw Rosetta regularly in the months and years following the funeral, remembers that, despite her temperamental buoyancy, Rosetta seemed noticeably down. At Mother Bell’s interment, as she watched the coffin being lowered into the ground, she had wept and told him, “Don’t let them put her in that cold, cold place.” As Roxie remembers it, Rosetta took her mother’s death as well as might be expected. “We were there with her, we talked to her, and we hugged her and we comforted her, and Ernestine . . . to have Ernestine there [at the funeral] was a big help,” she says. She and Louise never broke the deathbed promise they made to Katie Bell: they made sure they saw a lot of Rosetta that first year, especially Roxie, who for unrelated reasons spent part of 1968 living with Rosetta and Russell in the house on Master Street.

Rosetta cut back on her touring in the wake of Katie Bell’s passing. She also did less overseas traveling. “She was still going to places like Washington, you know, and nearby places and churches,” says Roxie. “She wasn’t doing the big things.” Those “nearby” places sometimes extended as far south as Florida and the Carolinas, in the small towns where Russell knew that the Rosetta of “Beams of Heaven” had never been forgotten. But for the most part, that part of her that loved performing had dimmed.

Condolences came in from Rosetta’s family, as well as from friends in Britain and Europe. Occasionally she even received a visitor from abroad. Willy Leiser shared Christmas dinner with Russell and Rosetta in December 1968, Rosetta’s first holiday without her mother. Leiser can still remember the spread Rosetta prepared: fried chicken, Virginia ham, greens, rice, sweet corn, salad, biscuits, and cornbread. After dinner, she sat at the piano and sang “Precious Lord’ ” in honor of her mother. On another occasion around that time, when Willy joined Russell, Rosetta, and their chauffeur for one of her appearances in Norfolk, they went to have a meal at a motel restaurant and were refused lunch service, although it was nearing 11:50 a.m. Not wishing to put up a fight, Rosetta and Willy ordered pancakes, only to see a parade of fish and chicken come out of the kitchen for the other “breakfast” customers. The final straw was when the white waitress who was serving them came out with one plate of pancakes, which she placed, with obvious intention, before Willy. “So, I pushed my plate toward Rosetta and said in my broken English that in my country, we served ladies first,” he remembers announcing. “My plate finally came, but I had to wait to be served until she had finished serving everyone.”

In the late 1960s, the label at the forefront of the gospel field was Savoy Records. Under the careful direction of producers Lawrence Roberts, a black Baptist pastor, and Fred Mendelsohn—like label founder Herman Lubinsky, a Jew from Newark—Savoy put out many of the greatest gospel records of the 1950s and ’60s, including work by Dorothy Love Coates, Clara Ward, the Caravans, and James Cleveland. Rosetta teamed up with Lubinsky and Mendelsohn in late 1968 and in quick succession released two LPs, Precious Memories and Singing in My Soul. Both consisted of new recordings, featuring Rosetta and a stripped-down rhythm section (organ, drums, piano, guitar), and yet both looked backwards, as though in implied tribute to Katie Bell. The nostalgically named Precious Memories, which earned Rosetta her only Grammy nomination, for Best Gospel Soul Performance, gathered together some of her most popular material: “Savior Don’t Pass Me By,” “No Room in the Church for Liars,” “Precious Lord,” “This Train,” and “Peace in the Valley.” Singing in My Soul took a similar tack, resurrecting old songs and giving new treatments to others; as Tony Heilbut noted, Rosetta paid homage to Katie Bell with the solemnly beautiful “When the Gate Swings Open.” In his album notes, Heilbut portrayed Rosetta as ahead of her time merely for having stayed so consistent to her musical vision, however the wind blew. “Today when every pop singer is returning to his roots,” he wrote, “Rosetta Tharpe’s music is truly where it’s at.”16

Rosetta was the featured female act at the 1970 American Folk, Blues and Gospel Festival, which began on October 26 in Germany. The pace was brutal: Copenhagen, Berlin, and Paris on three consecutive nights in the second week of November; Vienna, Frankfurt, and Bristol, England, on consecutive nights later in the month. With all the traveling, there was little time for sleep, let alone taking in the sights. It was around this time, recalls Rosetta’s French friend Jacques Demêtre, that she began complaining about not feeling well. Rosetta and Demêtre had first met in Paris in 1957, when Demêtre, who wrote about music for the French jazz press, got in the habit of picking her up and driving her to her concert appearances to save her the bother of a taxi. “She was very interested, not only by the neighborhood where her hotel was, next to Montmartre, but she also wanted to see the stores.” She was pleine de vie, he says, “simultaneously vivacious, energetic, gay, and full of feminine charm. In short, a very strong personality, who didn’t ‘play the star.’ ” In time, Rosetta, who had a bit of a crush on Demêtre, began complaining to him about her relationship with Russell; at one point, she even mock-proposed marriage. (Embarrassed but also flattered, he dutifully turned her down.) “Do you believe in God?” he remembers her asking while they were getting to know each other. “Not too much. In fact, not at all,” he conceded. “No matter,” she responded reassuringly, “I’m not a fanatical believer.”

When he reunited with her for the Festival show in Paris on November 9, Demêtre immediately noticed a decline in Rosetta’s health. “She was already—how can I say it—sick, and all of the sudden. She kept saying, ‘I don’t feel my hands.’ I don’t remember if it was her right hand or her left hand, but she had been visibly shaken by a bout of paralysis. My wife and I left that evening a bit anxious and it was later that we realized that we had been present at the first signs of the illness from which she would die in 1973. After that time, I never saw her again.”

Rosetta made it through the festival schedule as far as November 12, when she fell seriously ill in Switzerland and was taken to Geneva Hospital, where, by doctors’ orders, she was to rest up to get well enough to take an airplane home. Almost two weeks into her stay, when she was feeling a bit better, she gave a private concert for the doctors and nurses. One doctor even taped it. But Willy Leiser wasn’t altogether reassured by these displays of good humor. As it turns out, Rosetta had confided to him almost exactly what she had confided to Jacques Demêtre: “She told me that she felt numb in her arms, and I understood that it might be serious.”