Boredom sets in first, and then despair.

One tries to brush it off. It only grows.

Something about the silence of the square.

—MARK STRAND, “Two de Chiricos. 2. The Disquieting Muses”

The fact that a man does not realize the harmfulness of a product or a design

element in his surroundings does not mean that it is harmless.

—RICHARD NEUTRA, Survival Through Design

The headline to one of my early essays in architecture criticism, published in The American Prospect, was written by my editor, not by me. But when he sent along the galleys, it was clear he thought I’d pulled no punches: “Boring Buildings,” the title thundered. In the subhead I could almost hear my own plaintive voice, wondering “Why Is American Architecture So Bad?” Since that essay’s appearance fifteen years ago, our country’s and our world’s political, social, and economic landscapes have much changed. The events of 9/11 ushered in a far more perilous and increasingly self-conscious era. The Internet and digital technology changed how we communicate and how we shop, the nature of our right to privacy and even our sense of ourselves; they also rapidly accelerated economic integration and made globalization an economic, social, and cultural reality. Even so, fifteen years later, the indictment announced in that headline rings true, and not only in the United States.

Four Sorry Places

In the places we live, beggary casts a wide net, as four very different kinds of settings exemplify. The shacks inhabited by many millions of people on every continent except Antarctica make the case that built environments lacking in any sort of considered design greatly contribute to the degradation of human life. If we consider such slum dwellings in relation to the developer-built single-family houses that hundreds of millions more call home, however, we see that lack of resources constitutes only one part of the problem. Then, if we examine both alongside the design of a resource-rich high school in New York City, it becomes clear that people’s failure to accord their built environments sufficient priority plays an important role. And if we take all that information and synthesize it with what we can learn from an art pavilion in London designed by a Pritzker Prize–winning architect, Jean Nouvel, we see that even with ample resources, good intentions, and well-placed priorities, things go wrong. These four examples of built environmental beggary show how pervasively poor our built environments are, and suggest the complex reasons why. They also belie what slum dwellings by themselves might suggest: money, or lack of it, constitutes only a small part of the challenge.

Slums are an example where resources truly are scarce. In Haiti, one and a half million people lost their homes in the devastating 2010 earthquake, and many lived in the aftermath and continue to live in encampments of makeshift, temporary shelters. Among the thousands of heartbreaking images documenting the Haiti disaster was this photograph of a huddling row of shanties clutching to the median strip of Route des Rails in Port-au-Prince, where entire families inhabit tarp-covered one-room shacks with dirt floors. Cars and trucks rumble and speed by. No electricity. No plumbing. No privacy. No quiet. No clean air to breathe, fresh water to drink. Just unlucky people trying to maintain their rectitude and dignity in a built environment that pulls them down every day.

Life on the Route des Rails one year after the catastrophic 2010 earthquake, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Ruth Fremson/The New York Times.

Although this photograph depicts people struggling to survive in the wake of a singularly catastrophic event, the circumstances in which they live are unusual in only two ways: cars pass through this linear settlement very quickly, and fabric tarps cover their shacks instead of the usual corrugated metal, scraps of plastic, thatch, or rotting plywood or cardboard sheets. These Haitian shacks otherwise resemble their analogues: favelas in Brazil, bidonvilles in French-speaking countries such as Tunisia, townships in South Africa, shantytowns in Jamaica and Pakistan, campamentos in Chile, and to use the most generic name among the dozens of such appellations in usage, slums around the world. The names, the materials from which they are built, the destitution of shelter they provide, the degree of desperation within differs depending upon economy, culture, climate, and continent. But the basic living arrangements are the same. One, two, even three generations jammed together with their belongings in one or two insalubrious rooms that lack the basic infrastructure of power and sanitation.

Thirty percent of all South Asians, including 50 to 60 percent of the residents of India’s two largest cities, Mumbai and Delhi, live in slums; estimates of the population density of Mumbai’s Dharavi slum range widely, from between 380,000 and 1.3 million people per square mile—five to nineteen times that of Manhattan. Sixty percent of sub-Saharan Africans inhabit slums. Four million people dwell in the largest slum in the world, draped across the outskirts of Mexico City. All told, one out of every seven of the planet’s people, totaling one billion, and one-third of all urban dwellers call such places home. The Housing and Slum Upgrading Branch of UN-Habitat predicts that by 2030 the number of people living in slums will more than double, as slums are “the world’s fastest-growing habitat.”

How might a child growing up in a leaky shack in Port-au-Prince or Mumbai or Lagos be affected by the physical circumstances of his surroundings? Children who inhabit chaotic, densely populated homes exhibit measurably slower overall development than do children raised in more spacious quarters. They underperform in school and exhibit more behavioral problems both in school and at home. An acoustically uncontrolled space too tightly packed with people, with little privacy, correlates with disorder, explaining why crowded homes are associated with higher rates of child psychiatric and psychological illness. We know that the degree of control a child feels he has over his home environment is inversely related to the number of people per square foot who live there, and a diminished sense of control compromises a child’s sense of safety and autonomy, of agency and efficiency, and hence likely of motivation.

Slum dwelling in Africa. iStock.com/Delpixart.

This is just the most obvious way that the design of a shanty house compromises people’s lives. Overcrowding, lack of privacy, and environmental noise diminish a child’s capacity to manage her emotions and hinder her ability to deal effectively or even to cope with life’s challenges. So not only do slum-dwelling children enjoy fewer opportunities, but they are also less capable of taking advantage of the opportunities available to them. Even if an adult raised from birth on the Route des Rails unexpectedly encountered sudden good fortune, she would likely struggle, and struggle more than a woman whose childhood had not been permeated with such built environmental deprivation and degradation. A person’s experience of growing up in challenging and impoverished circumstances results in lifelong diminished capabilities.

It’s not only such patently deprived places, lacking in any sort of design, that diminish people’s well-being. Resource-rich middle-and upper-middle-class housing developments in the United States prove that. Consider two new ones that differ greatly in locale, price point, consumer base, and design. Lakewood Springs is in Plano, Illinois, a suburb approximately one hour’s drive west of Chicago. A relatively small middle-class development, its homes are arrayed on the paper-flat land that constitutes much of America’s midwestern plains. Stylistically, the architecture at Lakewood Springs reinterprets the traditional midwestern farmhouse in two basic models, with low-slung, single-story homes and two-story townhouses alternating along cul-de-sacs and gently curving streets. The second settlement can be found in Needham, Massachusetts, a development of McMansions. Homes here run larger, and though their configurations vary more widely, they hew stylistically to what might be termed Realtor Historicism.

Middle-class developer-built suburban home. iStock.com/Paulbr.

Size and price differences notwithstanding, the $200,000 house in Plano, and the $1 million house in Needham, share many basic features and problems. Each unit accommodates a single nuclear family. In spite of clear demographic trends toward the aging of our population, in spite of the growing variability of family composition, there is no place at Lakewood Springs or in Needham for elderly parents or for the disabled incapable of living on their own. Within each development, lot sizes are more or less identical (bigger in Needham), with houses plunked down at the lot’s midpoint, sandwiched between a front and back yard. Residents enter their homes through the garage, yet “front” doors gaze sorrowfully onto the street while “front” yards go largely unused. The layout of the homes and the scarcity of locally accessible services afford inhabitants limited opportunities for spontaneous social interaction.

Both in Plano and in Needham, these homes are tossed together from off-the-shelf materials using simple construction techniques requiring little skilled labor. Their environmentally suspect materials are cheap and thin; their timber harvested with little regard for sustainability; the PVC piping threaded through them leaching volatile organic compounds into the ground and the water the inhabitants drink; and gypsum walls that visually demarcate one room from the next offer but scant acoustic or thermal insulation. Carelessly standardized room arrangements and stock floor plans result in poorly placed windows and rooms with little attention to where the house happened to end up on the lot. No heed is paid to prevailing winds or to the trajectory of the sun’s rays. For example, in one house, the living room might be dark, while in another, it might blaze with sunlight; some bedrooms might be too cold, others too warm. Efficient thermostats and artificial light cloak poor design.

Higher-end developer-built surburban home. iStock.com/Purdue9394.

Okay, you may think, so these middle- and upper-middle-class housing developments aren’t great. Surely the homes and institutions and landscapes that serve more affluent people are better? Some are, but many more are not. Take my own experience with trying to find a school for our son. A few years ago, preparing to move to New York City from out of state, my family visited a number of private schools in Manhattan and Brooklyn in search for the right fit for our soon-to-be high schooler’s challenges and considerable abilities. Most families would be happy to send their children to a certain school in upper Manhattan. This pre-K–12 school occupies a collection of buildings abutting one another on a leafy side street; its entrance sits in a heavily shadowed, deeply sculpted, Richardsonian Romanesque masonry pile of earthy tans and reddish browns. But its high school, located in a newer building perhaps forty years old, looked a little less and a little more like a hundred suburban high school degree factories. Its many classrooms, below-grade, were rectangular cinder-block grottoes, with industrial-grade wall-to-wall carpeted floors and ceilings lined with standard-issue white acoustic tiles. Furniture for the classroom consisted of metal desks and chairs. Ninth-, tenth-, and eleventh-grade classrooms lined a narrow linoleum-tiled internal corridor, with sound bouncing around and off walls like so many balls on a crowded playground.

It got worse. Even though one of an adolescent’s principal challenges is to learn how to navigate an increasingly complex social world, only one large space explicitly facilitated this important pursuit, an informal gathering area that students called the Swamp, a nickname that conveys, presumably, not the room’s physical appearance but a student’s experience there. Forlorn castaway sofas floated in a cramped afterthought of a corridor, an unwelcoming muskeg that offered a prix fixe menu of social opportunities: being or not being part of a large, amorphous group. In the Swamp, teenagers buzzed like dragonflies and crickets and locusts, a deafening din.

Yet research clearly demonstrates that design is central to effective learning environments. One recent study of the learning progress of 751 pupils in classrooms in thirty-four different British schools identified six design parameters—color, choice, complexity, flexibility, light, and connectivity—that significantly affect learning, and demonstrated that on average, built environmental factors impact a student’s learning progress by an astonishing 25 percent. The difference in learning between a student in the best-designed classroom and one in the worst-designed classroom was equal to the progress that a typical student makes over an entire academic year. Students participate less and learn less in classrooms outfitted with direct overhead lighting, linoleum floors, and plastic or metal chairs than they do in “soft” classrooms outfitted with curtains, task lighting, and cushioned furniture, all of which convey a quasi-domestic sensibility of relaxed safety and acceptance. Light, especially natural light, also improves children’s academic performance: when classrooms are well lit—and most especially when they are naturally lit—students attend school more regularly, exhibit fewer behavioral problems, and earn better grades. Windowless rooms of the kind in the high school we visited exacerbate children’s behavioral problems and aggressive tendencies, whereas daylit, naturally ventilated classrooms contribute to social harmony and facilitate good learning practices. And the sort of noise that we heard that day detrimentally impacts learning, just as it does children’s sense of well-being at home, communicating to inhabitants their lack of control over their surroundings. This in turn elevates their stress levels, further inhibiting their learning.

Why did this school and why do so many of this country’s schools construct these kinds of inadequate buildings for their high schoolers? Why, today, in light of readily available research demonstrating that the design of learning environments can inhibit or advance pedagogical objectives, do they continue to use them? The particular high school we visited that day is neither a for-profit institution nor a cash-starved, high-aspirational nonprofit. The reason the school’s board of trustees didn’t consider it a top priority to create a physical plant that supports students and facilitates their transition to college and emerging adulthood was not so much a lack of concern or resources but a lack of awareness.

A school building that helps students learn: Sidwell Friends Middle School (Kieran Timberlake), Washington, DC. © Albert Vecerka/Esto.

What about when clients do recognize design’s importance, and are willing to devote ample funds to it? Even then things go wrong. Consider one of the pavilions built by London’s popular Serpentine Galleries, which annually selects an internationally celebrated architect to design a temporary pavilion in Hyde Park. Crowds throng the annual Serpentine Pavilion; many more who don’t make it to London see it in the style pages, or online. In 2010, the globe-trotting French starchitect Jean Nouvel took the Serpentine commission’s impermanence and flexibility as license to construct a luxuriously finished, angularly diagonal cacophony of steel, glass, rubber, and canvas, with blazing transparent, translucent, reflective, and opaque red surfaces. Explaining that he wanted to evoke the image and sensations of a setting summer sun, Nouvel romantically recounted his “building from a dream,” an expressive place to “catch and filter emotions, to be a little place of warmth and delight” where people can have “some, I hope, happy sensations.”

Nouvel’s pavilion looks terrific in photographs, like a red thunderbolt shot through the verdure of Hyde Park. But I doubt that the people who visited it lingered there to play on its bloodred oversize chessboard, and I can nearly guarantee that fewer still experienced the happy warmth and delight that Nouvel aspired to elicit. That is because his three most significant design decisions—sharp angles, diagonally canted walls and ceilings, and the large-scale use of the color red, including red-tinted glass for the windows—were guaranteed to undermine rather than advance his intentions. Instead of “happy sensations,” it’s far likelier that visitors to that year’s Serpentine Pavilion felt an uneasy sense of stress, even anxiety.

Humans respond to compositions dominated by sharp, irregular, angled forms with discomfort, even muffled fear. The color red and red light stimulates people, but generally not in a pleasant way. We know that when infants or people suffering from mental illness are exposed to red light, anger and anxiety are heightened. Normally functioning adults, when placed in red rooms or exposed to intense red light, suffer a diminishment of problem-solving and decision-making abilities and a reduced capacity to engage in productive social conversation. An all-red environment shifts the human pituitary gland into high gear, raising blood pressure and pulse rate, increasing muscular tension, and stimulating sweat glands. Such a place can energize and excite us, to be sure, but it’s the kind of excitement that’s coupled with agitated tension and can easily slip into anger and aggression.

2010 Serpentine Pavilion (Jean Nouvel), London, England [demolished] © James Newton/VIEW.

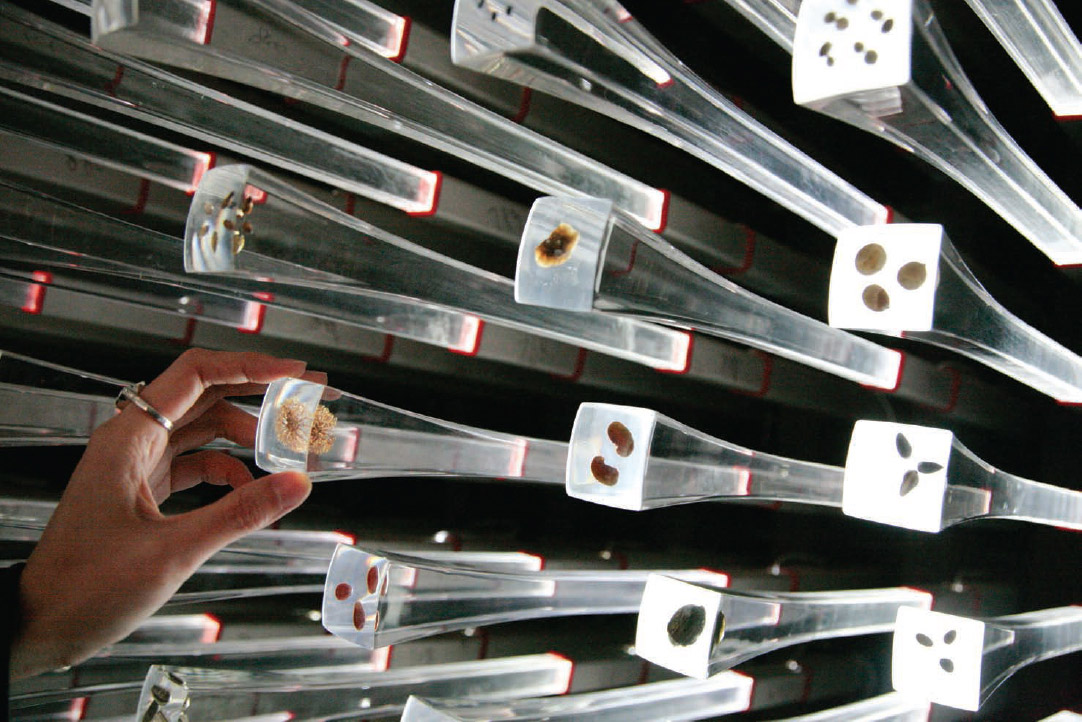

Imagine being inside Nouvel’s pavilion, then compare that experience to standing next to or inside a different temporary exhibition pavilion, Thomas Heatherwick’s Seed Cathedral, constructed the same year as Nouvel’s to represent the UK in the World Expo held in Shanghai. Built on a modest budget, Seed Cathedral’s dandelion-like structure was set into a silvery, Astroturf-covered landscape. Protruding from the inside and the outside of a simple wooden box were 60,000 clear acrylic rods, their tips embedded with one or several seeds—a total of 250,000 of them, harvested from Kew Gardens’ Millennium Seed Bank. The Seed Cathedral’s evenly spaced, pappus-like transparent rods captured the light of the sun and transmitted it into the pavilion’s interior. Each individual rod also held a tiny light source, so that at night, the feathery Seed Cathedral displayed literally 60,000 points of light, softly swaying in the wind.

Same year, two pavilions, totally different experiences: Nouvel’s excited agitation, Heatherwick’s inspired gentle delight. The comparison starkly illustrates how much our thoughts and even our moods can be influenced by the design of the environments we inhabit when the environments are at the extreme. Yet this is also, and profoundly, true for ordinary and conventional design.

These accounts of shacks in slums, suburban developments, a New York City high school, and London’s 2010 Serpentine Pavilion all exemplify failures of the built environment. Such failures happen far, far more often than not. The example from Haiti shows what happens when grossly insufficient resources are devoted to the places we live: such places are all but doomed to be wholly inadequate, indeed harmful to their occupants. But the next three examples—the suburban housing developments, the high school, and the elite art pavilion—complicate the story considerably. Individually and collectively, they demonstrate that even when people devote resources to design and construction, things can still go very wrong.

Why have we been condemned to live in mostly boring buildings, to spending a good deal of our lives in landscapes and places distinguished mainly by their beggary?

The answer is not primarily resources. At virtually any level of resource allocation, as measured by cost, design can be poor or better, with better design enriching buildings, landscapes, and urban areas. As we will see, even housing for the world’s poorest can be better than the slums and favelas in which a billion people live. And plenty of resources were channeled into the Plano and Needham developments. The problem was an overly conventional and narrowly bottom-line approach to decisions about the design of their buildings, infrastructure, and landscapes, resulting in stultifying environments that functioned far less optimally—or to put it negatively, far more harmfully—to the well-being of its inhabitants than they could have. The New York City school’s trustees lacked neither resources nor good intentions, but they likely wanted for knowledge about the multiple profound effects of design on students’ cognitions and emotions, learning and achievement, individual well-being and communal cohesion. Yet as the 2010 Serpentine Pavilion illustrates, even when educated clients with deep pockets hire truly gifted designers, success is by no means guaranteed.

Seed Cathedral, 2010 World Expo Pavilion (Thomas Heatherwick), Shanghai, China [demolished]. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Seed Cathedral, detail showing seedpods encased in resin rods. Kevin Lee/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Why do developers build single-family houses that are patently wasteful and do not serve contemporary living patterns? Why did the board of trustees of an elite high school use for so many years a building that failed to promote learning—in fact, very likely inhibited it? Why did Nouvel, an internationally acclaimed leader in the field and an architect who has some excellent buildings to his name, fail to create the “happy” pavilion he believed he had designed in Hyde Park?

The problem is an information deficit. If people understand just how much design matters, they’d care. And if they cared more, they’d change.

A Bird’s-Eye View of Built Environmental Beggary

Let’s zoom away from these initial four examples to examine our landscapes around the globe with fresh eyes. In what ways are, and are they not, the ones that people need? From low building to high architecture, from metropolitan planning to suburban design, from streetscapes to landscapes, the examples discussed above represent a much larger, indeed all-too-common reality. Even in resource-rich countries and cities and institutions, people live out their lives in misconceived, poorly designed, and badly executed places. Billions suffer the consequences, mostly clueless that the origin of many of their social, cognitive, and emotional problems may lay directly beneath their feet and above their heads.

Discard the notion that design is a discretionary luxury. The built environment affects our physical health and our mental health. It affects our cognitive capabilities. And it affects the ways we form and sustain communities. The built environment affects each of these facets of our lives, and because they are related to one another, it does so in ways that are mutually reinforcing. Our asphalt-draped cities starve us out of a healthy ongoing relationship with nature. Wherever we look—at infrastructure or urban areas or suburban settlements; at landscapes or cityscapes or individual buildings, the bottom line is boring buildings, banal places, and hoary landscapes.

The Infrastructure of Urban Life

Infrastructure provides the cylinders in any country’s engines of economic growth, yet in developing countries and many wealthy countries—and in the United States—infrastructural design and maintenance is in a deplorable state, revealing how little our society values even those parts of the built environment that are essential to economic growth. We traverse crumbling bridges and corroded, eroding pipes that occasionally blast their way into the public awareness. In the United States in 2013, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), one infrastructural system after another fails us with insufficient capacity, deplorable condition, and more. The ASCE scores our society’s most essential structures and systems on the same scale every schoolchild knows. Our “report card” is shameful: public transportation systems earned a D+, roads, a D, and public parks and recreation facilities, a C+. Decades of neglect meant that in 2013, to bring our infrastructures up to minimum standards, $3.6 trillion in the next seven years was needed. While the infrastructure of Japan and much of Western Europe is in better shape, many more countries in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia suffer with infrastructures that remain poor or effectively nonexistent. In India the situation is so extreme that in some places, private citizens have taken to hiring their own contractors to construct roads, sanitation systems, even bridges, resulting in a piecemeal infrastructure that serves mainly those who pay. In much of Africa and Latin America, infrastructure for water distribution, sanitation, transportation, and information technology simply does not exist, and in Latin America, recent reports suggest that public investment in these systems appears to be diminishing.

The character of cities in the developed world—those of rapidly growing Asia, those of increasingly urbanized Latin America and Africa—differ from one another markedly. Even within these vast regions, variations are enormous: just as Washington, DC, differs from New York City, Beijing is quite unlike Shanghai, let alone Mumbai, Lagos, Los Angeles, and São Paulo. But whatever their variations, many cities around the globe suffer from the impoverishment of thoughtlessly created urban spaces. The “green” spaces they lack or pretend to provide, the materials and quality of construction of their buildings and landscapes, the relationship of their buildings to their sites—all fail to promote and many actively undermine the welfare of their citizenry, individually and collectively.

Faulty design can kill: in 2007, the I-35W bridge in Minneapolis collapsed during rush hour, killing 13 and injuring 145 people. AP Photo/Morry Gash.

Humans crave and need access to the outdoors and to nature and suffer in its absence, yet few of us appreciate how fundamental that need is. Contact with nature confers on people salutary effects that are nearly immediate. Twenty seconds of exposure to a natural landscape can be enough to settle a person’s elevated heart rate. Just three to five minutes will suffice to bring high blood pressure levels down. Nature, quite literally, heals us: hospital patients recovering from gallbladder surgery, when placed in rooms with views of deciduous trees instead of rooms facing a brick wall, healed so much more quickly that they were released from the hospital nearly a full day earlier. Even during their hospital stay, they felt less perceived pain as measured by how frequently they requested pain medication.

Not surprisingly, then, people’s preferences for urban environments also consistently skew toward nature, and cities containing ample green space consistently rank higher on lists of desirable places to live. When people in one large study were asked to prioritize a list of features that they would use to determine a neighborhood’s desirability, “access to nature” consistently ranked first or second. Merely the view of grass and other greenery from a residential window increases the likelihood that an inhabitant will be satisfied with his neighborhood. And still, in spite of it all, many of the world’s major cities contain, shockingly, less than 10 percent green space, including Bogotá (4 percent); Buenos Aires (8.9 percent); Istanbul (1.5 percent); Los Angeles (6.7 percent); Mumbai (2.5 percent); Paris (9.4 percent); Seoul (2.3 percent); Shanghai (2.6 percent); and Tokyo (3.4 percent). When it comes to the inclusion of nature in cities, political will emerges as a determining factor: many of the cities containing 35 percent or more green space are located in countries where the government takes a strong hand in managing public resources and is devoted to the public welfare: London, Singapore, Stockholm, and Sydney.

From the point of view of public health and human welfare, many of the world’s cities—and suburbs—are wanting not only in their open spaces but in the poor quality of their construction and the cheapness of their materials. After every natural disaster we learn whether or not a given city is riddled with poor quality concrete that crumbles and cracks soon after the mixing trucks disappear. Suburbs and cities are laced with low-grade timber and shoddily manufactured, toxin-emitting composite woods. Everywhere, cloddishly designed mullions and moldings knit together haphazardly, inexpensive plastics—this is the stuff of which our urban environments are mostly made. Cheap construction disintegrates. Cheap buildings make cities that cheapen lives.

Even though we know more than enough about human physiological and psychological needs to know that buildings and cities must accommodate more than basic functional necessities such as sleeping and eating, they must also nurture our social connections and sense of belonging to a community. And even though we know that communities gain character through their interaction with distinctive, geographically identifiable places, woeful inattention is paid to such features of human social interaction, or to how buildings relate to their sites. Workplaces all too often neglect people’s need for privacy. Although load-bearing brick makes sense for buildings in rainy, muddy climates but less so in drought-prone regions, all too often the design of buildings from these different climates is more or less identical. Contractors, instead of harvesting materials locally, ship them in bulk, transcontinentally. Local construction practices are neglected or deliberately forsaken. This lack of attention to local climates, cultures, materials, and construction practices is owing, in many places, to much too much building too quickly, as is the case in China. In other places, such as the cities of sub-Saharan Africa, it is owing to an absence of considered planning and regulation.

Some of the ways that unimaginative or inattentive urban design harms us is invisible. Stand on a street corner in any major city, close your eyes, and listen. Brakes screeching. Truck cargo clanking. Engines gunning. Fire engines and ambulance and police sirens piercing their way into your ears. On any given day, in any given American city—Chicago, Dallas, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, Phoenix, and San Francisco—the ambient noise levels on busier streets significantly exceed the 55–60-decibel (dB) level of normal conversation, which is what public health authorities at the US Environmental Protection Agency and the WHO deem safe for everyday living. Noise levels on New York City’s subway platforms frequently approach 110 dB, which approximates the experience of standing three feet from a running power saw. And while most public health authorities agree that urban noise levels should never exceed the jet-engine-taking-off-140 dB for adults (120 dB for children), they do. The European Union is no better: 40 percent of EU residents—whose countries offer among the highest general standard of living in the world—live subjected to noise levels loud enough to imperil their health and well-being. In developing countries, where noise protection ordinances are fewer and inconsistently enforced, the situation is immeasurably worse.

Harmful noise levels on New York City subway platforms. AP Photo/Mary Altaffer.

Hearing loss constitutes only the most obviously harmful effect of excessive noise. The World Health Organization outlines the detrimental effects of noise on other aspects of human health. As we’ve seen, it diminishes people’s sense of control over their environments. Noise levels higher than 30–35 dB in residential neighborhoods disrupt people’s circadian rhythms during sleep (even if they never actually wake up); disrupted sleep, in turn, contributes to a wide range of physical and emotional problems. Exposure to continuous environmental noise higher than 55 dB alters people’s respiratory rhythms, and detrimentally affects our cardiovascular systems at noise levels of 65 dB or higher. When environmental noise levels exceed 80 dB (more or less equivalent to the sound of heavy truck traffic on a highway), aggressive behavior and vulnerability to mental illness increase.

Children who attend schools situated near airports consistently demonstrate impairment on a host of cognitive faculties that critically facilitate learning, such as concentration, persistence, motivation, attention to detail. With diminished capacity for reading comprehension, these children fall behind on achievement tests. Even an occasionally passing train disrupts children’s ability to learn. One study compared the academic performance of two sets of students at an urban school located on a site adjacent to elevated train tracks. Those students whose classrooms faced the train tracks consistently underperformed on a wide range of tasks relative to their peers in quieter classrooms located just across the hall.

Stress, noise, and crowding in developing countries, Dhaka, Bangladesh. AP Photo/John Moore.

Suburban Living, Suburban Landscapes

Suburbs purportedly offer quieter, more pastoral havens from the ills and travails of urban life: that’s why people move to them. But the design of many suburbs impoverishes people’s lives in other ways. Like Plano or Needham, many suburban landscapes discourage people from developing a meaningful sense of place. Why? For generations, most suburban developments have been and continue to be constructed by large regional or national real estate concerns: in 1949, close to 70 percent of the houses constructed in the United States were built by only 10 percent of the country’s builders—and the home-building industry is more consolidated today than it was fifty years ago. Companies such as D.R. Horton, NVR, and PulteGroup pay minimal attention to a locale’s climate, a site’s topography, and to where they source their materials. The logic driving the site plans, building designs, and landscaping schemes they generate is profit, so their playbook is written to convention and maximum iterability in design, and in ease and speed of construction. Day in and day out.

Outdated land-use ordinances and building codes exacerbate these problems. Many municipalities retain zoning laws written in and for a different era, which violate best-practices urban design for the twenty-first century, such as community-oriented, sustainable, and mainly denser, mixed-use developments. Zoning laws that discourage density and cordon residential areas off from workplaces, light industry, and even retail establishments force even enlightened developers to overcome extra hurdles to make vibrant suburban communities. Anachronistic building codes discourage healthy experimentation, the widespread adoption of improved materials and newer, superior methods of construction. Again and again, innovation is forsaken for the ease of conventional compliance.

People who move to the suburbs in the hopes of a healthier lifestyle and more connection to nature can find themselves suffering problems they didn’t anticipate. Suburban life remains primarily about the car: to get your kids to school, you drive; to get groceries, you drive; to get to work, you drive; to run errands, you drive. The typical suburban neighborhood, scaled to the view at thirty or forty-five miles per hour, and to the turning radius of the steering wheel, is designed for driving over walking or biking. One result is that many such developments promote lifestyles so sedentary and auto-dependent that America, and increasingly much of the developed world, is facing an avoidable public health crisis. As public health authority Richard J. Jackson bluntly puts it, “the more time we spend in a car, the more likely we are to be obese”—and this is without even taking into account the enervating, resource-and time-draining costs of commuting. An auto-bound, sedentary lifestyle is part of why nearly 40 percent of adult Americans are obese, and fully 70 percent are overweight—compromising people’s cardiovascular health and general muscular capacity, and greatly increasing their vulnerability to type 2 diabetes.

In the name of privacy, suburbs can cultivate social isolation and promote the kind of social and ethnic homogeneity that breeds intolerance. Suburbanites, instead of rubbing shoulders with people of wide-ranging backgrounds, outlooks, and sensibilities, are deprived of the (well-documented) humanizing and socializing effects of being active in a diverse public sphere. They also lose out on the well-established psychic and social benefits of being enmeshed in closer and looser networks of people. And these failings are evident in suburbs across the country, from those that surround New York on Long Island and in Westchester County and northern New Jersey, to Dade and other counties in Florida, to the vast sprawls that are Dallas and Phoenix, to Orange County and many other counties that make up the California megalopolises known as Los Angeles and the Bay Area.

Highway commuting. Scott Olson/Getty Images.

“Boxed, bleached sameness”: Las Vegas suburbs, aerial view. iofoto/Shutterstock.com.

One principal reason that people move to suburbs is well known: they wish to claim a little piece of nature as their own. Yet paradoxically, suburban developments do more to dissociate people from the varied experiences that a good natural environment provides. Psychologists have demonstrated again and again that people are invigorated and soothed by nature’s compositions, but nature tamed by suburbia can seem like assembly-line “softscapes”: simplistic, repetitive arrangements of shrubbery and grass draped over swaths of land feel more stultifying than uplifting. Theo, the protagonist in Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, hilariously recounts his gobsmacked impressions of the exurbs of Las Vegas, where he unexpectedly lands: “I looked up and saw that the strip malls had given way to an endless-seeming grid of small stucco homes. Despite the air of boxed, bleached sameness—row on row, like a cemetery’s headstones—some of the houses were painted in festive pastels (mint green, rancho pink, milky desert blue) . . . As a game, I was trying to pick out what made the houses different from each other: an arched doorway here, a swimming pool or a palm tree there.” Later, Theo observes that “there were no landmarks, and it was impossible to say where we were going or in which direction.” In the interior spaces of these cookie-cutter domiciles, the same sort of tedium exists on a smaller scale. The simulated woods found in the kitchen cabinets and flooring of such developments manifest little of the visual, textural, and olfactory complexity that people yearn for. Such features, all typical in suburban developments (and in many urban developments as well), constitute a catalogue of larger and smaller missed opportunities, rendering suburbs as inimical to human well-being as the urban experience they were supposed to rectify.

Neither cities nor suburbs consistently integrate considerations about landscape into their design. The public spaces outside buildings—lawns, squares, plazas, parks, cultivated and uncultivated outdoor areas wholly or predominantly made up of the greenery of trees, plants, flowers, and grasses—are much more often than not an afterthought, deemed unworthy of attention or design. In cities, we find perhaps a sculpture or a few sad benches; in suburbs, unvariegated lawns, punctuated by the occasional lonely bank of shrubs.

Landscape design in most suburban developments barely exists. IP Galanternik D.U./Getty Images.

Boston’s massive Central Artery/Tunnel Project—the Big Dig, as it became known—betrays the pervasive public apathy and governmental ineptitude when it comes to the design stewardship of our landscapes. The Big Dig dismantled the elevated part of Interstate 93 that cut through downtown Boston, putting the highway underground and restoring a strip of land that could have been used to knit the riven city back together. During its construction from 1990 to 2007, it was the largest, most expensive urban project in the United States, and its final price tag, more than $24 billion, made it the most expensive stretch of roadway in American history. Yet for years after its completion, the city of Boston and state of Massachusetts spent more servicing the debt for the project—$100 million—than was devoted in total to the entirety of the surface landscape that the Big Dig created. By commission or omission, nearly everyone involved in the project treated urban design, architecture, and landscape as an afterthought. Years passed before anyone even figured out what to put there. As a result, close to a decade later, the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway’s public spaces, broken up by cross street after cross street, are less designed than planted, making its formal name more a term of self-parody than a descriptor. Six years after it opened, the Boston Globe reported that “one-third of the 20-acre Greenway is unfinished, with some parks lacking basic furniture and signs, and parcels that were slated to host museums and cultural institutions remaining barren”; a recent visit confirmed that not much has changed.

More planted than designed: Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway, Boston. AP Photo/Elise Amendola.

Builders and Architects: Decision-Makers and Decisions

Boring buildings and sorry places are nearly everywhere we turn. So, who exactly is in charge of our built environments? Who are the decision-makers, and what kinds of information do they have available to them? What kinds of decisions have been made in past generations? What kinds of institutional structures are in place to which today’s decision-makers remain bound? And what kinds of actions could they take that negatively or positively impact how we, our children, and our children’s children will live out our lives?

Among the groups exerting influence on the design of our built environments, the largest are construction companies, product manufacturers, and real estate developers. These are businesspeople, driven by profits. Collectively, the construction trades constitute one of the least efficient and most deplorably wasteful industries in the United States. And because most construction companies, unlike companies in most sectors of the economy, invest little in research and development, they are highly averse to innovation. What’s more, construction companies and the manufacturers of building materials, fixtures, and finishes give high priority to factors—for example, cost and ease of transport and storage—which relate tangentially or not at all to the needs of a project’s eventual users. Construction companies and manufacturers of products for the built environment take an approach to design analogous to that of the highly profitable home-furnishings giant Ikea, which mandates that designers’ products not only be easily assembled by consumers but also be easily stored in their colossal warehouses, with every product’s component parts fitting into packages that lie flat.

Real estate developers, whether residential, commercial, or mixed use, contend with multiple constraints beyond labor costs, zoning, and building codes. What and how developers build depends upon the state of the economy and its projected growth, financing vagaries, municipal ordinances, the quality of available labor, the nature of the building products on the market. The time horizon on which developers operate is set by marketplace exigencies, and bears little to no intrinsic relationship to promoting quality design and careful construction. Some developers, like Jonathan Rose in New York City, may be driven by broader social goals—choosing impoverished areas to erect their projects, constructing sustainable, well-designed affordable housing—but the fact remains that real estate development is business. Without enlightened regulation and demand, the public good can be served in a sustained way only to the extent that doing so reaps a profit.

In coming chapters we discuss examples in many sectors, from manufacturing to retail to office space, of profitable, innovative, good design. Yet the current structure of real estate development mostly discourages high-quality products and experimentation. For nearly any project, securing financing, pulling permits, and executing construction takes months to years. The high interest rates that developers pay investors, usually banks, to finance a new project creates enormous pressure on them to complete a project as quickly as possible. All this perpetuates powerful incentives for developers to employ established site plans and ready-made building designs; to rely on familiar, readily available, off-the-shelf materials; to use them in the most conventional ways; and to settle for standard (and more often than not, actually substandard) construction practices.

What about designers? Surely they must be more attuned than developers to people’s experiential needs. After all, most design schools train their students not only to minister to commissioning clients but to envision their role as guardians of the public realm, working to enhance the overall vitality of a city or place. Still, the reality remains that designers work for clients (which includes developers) and are subject to the same market forces as they are. The results of these market structures and limitations, and of the decisions of people working within them, constitute our built environments, not just in small-change residential and commercial developments but even in the highest profile projects. Consider, for example, what happened in the case of One World Trade Center, built on the hallowed Ground Zero in New York City’s lower Manhattan. Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, architects of some of the most innovative skyscrapers in the world, including the Burj Khalifa and the Cayan Tower, both in Dubai, the many clients of One WTC (the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the developers Larry Silverstein and the Durst Organization) whittled away at the architects’ design until by the time One WTC opened, it had devolved from a soaring, inspiring monument into three disaggregated components—base, shaft, and spire—that looked as though they’d been cobbled together by toddlers on a preschool floor. The glass shaft crashes into its clunky bunker of a base, which is scantily clad with glass fins like a prison clad in a sequined leotard. To make matters worse, at the eleventh hour, the spire was denuded by the Durst Organization of the elegant encasement the architects had designed for it. Too taxing on the company’s owners’ pocketbooks.

One WTC, like the London 2010 Serpentine Pavilion, shows that engaging the services of talented, highly trained professionals is no guarantee of success. Sometimes market pressures, transmitted through ignorant clients, are to blame. Just as often, though, designers simply lack sufficient knowledge about human environmental experience. This deprives them of their most compelling argument to advance good design—its powerful effects on human health and well-being—a lacunae that stems in part from the anachronisms of architectural education. Very few schools of design—with rare exceptions—offer, much less require, training in how humans experience the built environment. Courses in sociology, environmental and ecological psychology, human perception and cognition appear infrequently, if at all, in their curricula. The national accreditation boards do not mandate such studies as an essential part of professional training. Students learn about many basic and esoteric systems of design logic—complex geometries, structural systems, manufacturing and construction processes, parametric design. These are all important subjects, but only when combined with a curriculum that teaches students how the people who will use their projects will actually perceive, live in, and understand them. Of the built environment’s effects on human cognitive and social development, students learn next to nothing.

The architect’s rendering of One WTC tower (at left, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill), depicts a light base and an angled shaft, neither of which was executed as designed. New York, SPI, dbox via Getty Images.

Instead, design studios, where students receive direct training in how to conceive and realize a project, are often organized in a way that maximizes the competition for their professors’ regard. The result is that students gravitate toward and are usually rewarded for dramatic, gestural, attention-grabbing forms, designs that pack the maximal visual punch. Unusual forms and statement architecture reinforce budding designers’ impression that their projects are singular, discrete objects isolated from their environmental and urban context, and not intimately tethered to how actual people will experience and use them. Jeff Speck, an influential urbanist, explains the deleterious impact of such dynamics when it comes to conceptualizing very large projects: “Architecture students are taught that when you have a block-scale project, it’s not only your right but your architectural obligation to make it look like one building. But walking past 600 feet of anything is less enticing than walking past a series of 25-foot segments of different things.” A pervasive reliance on computer-aided design can further exacerbate the student’s inexperience with scale that is a result of designing buildings as isolated, discrete objects. Drawing by hand—one means by which students can absorb the art of designing for the human scale and perceptual faculties—has largely fallen by the wayside.

When students enter practice, the emphasis on striking visual compositions that they learned in school is often perpetuated. In taking on a commission, whether it be an art museum or a sewage treatment plant, the architect, landscape architect, or urban designer faces a mind-boggling array of disparate tasks, many of them requiring different skill sets. She must learn enough to grasp the nature of that particular institution, listen to and interpret her clients’ stated needs, and reality-test them against budgetary and other constraints. She must develop a comprehensive analysis of the site and its topography. She must acquaint herself with local building and zoning codes, construction practices, and materials. Out of it all, she must imagine a holistic solution, and then work out, step by step and beam by beam, how people can construct her design so that it becomes a concrete object in the world. Designing anything that will become an enduring feature of the built environment is a demanding, complex—indeed, a daunting—challenge.

The designer’s literal task at hand is to create a three-dimensional, physical object or setting; her job—object-making—and the dictates of the design process train her focus on composing forms. But the design process is conducted mostly on a scale that is minuscule in comparison to the end product. In these circumstances, considerations of user experience—how a place works at the scale of the city or its site, how it comes to feel and serve its users over time and in different seasons, the granular details people notice when moving through spaces, the non-conscious responses people will have to a project’s small-scale and less visible features, such as sound, materials, textures, and construction details—all this can remain in the lowlight.

The nitty-gritty of the design process inclines professionals to privilege a project’s overall compositional and pictorial aspects, which is a tiny slice of how it will function in people’s lives. Compounding the problem today is that professionals rely heavily on two-dimensional imagery—photographs, digital simulations—to market their services. They self-publish photographic monographs and construct elaborate websites to advertise their work. One highly respected contemporary architect, describing his process to me, confessed only half-jokingly that he always keeps in mind what his project will look like in photographs: “It’s all about the money shot. That’s what we design for.” Why? Because that’s what potential public and private clients, as well as jury commission members and colleagues will see and likely remember in making these decisions.

What information does a photograph actually offer about a building or space? Not much. Photographs confer the impression of veracity, but distort a multitude of compositional and experiential features. Pictures notoriously distort color, so that a concrete building you expected to gleam white could turn out to be a dull, thudding gray. Pictures fail to capture the ethos of a place: how it sounds or smells, or how its materials feel. Money shots appeal only to our visual senses, and only depict a single moment in the best light of day. But buildings and landscapes exist in three dimensions and are experienced in four, looking and feeling different at dawn than they do at dusk, different on gray days than on sunny days. How grossly photographs misrepresent built environmental experience, especially scale, was brought home for me when a Venezuelan-born acquaintance returned from seeing Lúcio Costa’s and Oscar Niemeyer’s famous capital complex in Brasilia. These are some of the most iconic monuments of late modern architecture in the world. In real life, she reported, those buildings looked as though they had been built at half scale. “They were no bigger,” she exclaimed, “than my health club in Caracas!”

Photographs distort and prettify: Secretariat and Chamber of Deputies (Oscar Niemeyer), Brasilia, Brazil. Magda Biernat/OTTO.

Many, if not most published (and posted) photographs of contemporary projects are commissioned by their designers. These not surprisingly elide all sorts of information—indeed, anything that might hinder their solicitation of new clients. Pictures of Zaha Hadid’s enormous, blazing white Dongdaemun Design Plaza, set in a green landscaped park, make it seem visually arresting, like some breathing, pulsing giant whale beached in a sunken plaza in downtown Seoul. Looking at the real building rather than photographs reveals that Hadid’s complex is bedeviled by cracking concrete, misaligned joints, and a landscaping scheme so uninspired that what was once green has dried into an insipid brown. Similarly, photographs of another widely celebrated project, the Seattle Central Library by Joshua Prince-Ramus and Rem Koolhaas’s OMA, do not reveal the building’s self-absorbed hermeticism, its utter failure to connect to the street-level spaces, to knit it into the city’s larger public realm. They mask its haphazard detailing. And they obscure the fact that the library suffers a dearth of quiet, comfortable spaces to read. The main reading room, located on the tenth floor, frustrates many over-forty readers hoping to settle in for a long day’s work, as the nearest restroom is located three floors down. These examples could be multiplied by dozens, illustrating how photographs of the built environment, and the photographers behind the lens, present the illusion of verisimilitude while unwittingly and willfully misrepresenting precisely what they purport to depict.

A Self-Perpetuating Cycle of Sorry Landscapes

The cognitive revolution’s complete rethinking of human experience reveals much that should make us all reconsider what we know about design. We respond to our environments not only visually but with our many sensory faculties—hearing, and smelling, and especially touching, and more—working in concert with one another. These surroundings affect us much more viscerally and profoundly than we could possibly be aware of, because most of our cognitions, including those about where we are, happen outside our conscious awareness. The leaders of the cognitive revolution reveal—perhaps mostly inadvertently—that our built environments are the instruments on which this orchestra of our senses plays its music. Just as we imagine waving with the conductor as we listen and watch the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, when we navigate and inhabit our environments, what and how we consciously think is inexorably bound up with our nonconscious simulations and cognitions, and with what and how we feel. Most surprisingly, our emotions, our imagined bodily actions, and especially the memories that we develop of them are embedded in our very experiences of built environments, and loom large in how we form our identities.

Most people don’t think about the built environment much at all, and certainly not in any systematic way. Our buildings and cityscapes and landscapes command a vanishingly small platform in the media and the public sphere. How many substantive articles about the built environment does your favorite newspaper or website feature? And how many of those contain actual analysis rather than featuring simple presentations?

For many reasons, most people mostly ignore cityscapes and buildings and landscapes. The two obvious reasons for this are that buildings and streets and plazas and parks rarely impinge on our conscious experiences. They change slowly, if at all. And we are animals: neurologically, wired to ignore all that is static, unchanging, nonthreatening, and seemingly omnipresent.

We also mostly ignore our built landscapes because practically, we have no obvious stake or influence in their production. This aligns with our approach to other swaths of our daily experience and needs: for medical help, we go to doctors; to repair our car, we visit the auto mechanic. Most of us, implicitly or explicitly, have relinquished control over our built environments, having entrusted decision-making about them to the putative or established experts: the city council members, the real estate developers, the builders and contractors, the product manufacturers, and the designers. Most of us perceive ourselves as helpless to make changes in the built environment. This very sense of powerlessness results in a paradoxical situation: real estate developers configure new projects based on what they believe consumers want, which they assess mainly by examining what previous consumers have purchased. But when it comes to the built environment, consumers gravitate toward conventional designs without thinking very much about them. So developers continue to build what they think people want. No one steps back to consider what might serve people better, what people could like, or what they actually might need.

Not only are consumers disposed to prefer familiar, conventional designs, they will prefer conventional designs even if those designs serve them very poorly—which, as we have seen, they often do. This is owing to a common psychological dynamic, namely that the more times a person is exposed to a stimulus, even if it does not serve her well, the more she will habituate to it such that she eventually will not only prefer it when offered other options, but will eventually deem it to be normative. In this way, people can and do come to judge inferior places that serve them poorly, or even harm them in covert ways, as indisputably, objectively good.

This self-perpetuating cycle of built environmental inertia in which we are caught must end. Thanks to the cognitive revolution, the news is in: impoverished cityscapes and buildings and landscapes impoverish people’s lives. Do we really want the inertia of convention, the profit margins of lenders and developers, anachronistic zoning and building codes, criteria such as the width of roads and flatbed trucks, to determine how our cities and institutions look and function and feel? Shouldn’t we be rethinking design of all kinds, including its standardization, in light of all we know about what people actually need?

In the wake of the cognitive revolution, we must recognize the reality that aesthetic experience, including our aesthetic experience of the built environment, concerns more than pleasure, so much more that the conventional distinction between architecture as the province of the elite, and building as the province of the masses, must once and for all be eradicated. From our perspective—the perspective of how human beings experience spaces, of how built environments affect our well-being—such a distinction is incomprehensible and pernicious. The more we learn about how people actually experience the environments in which they live their lives, the more obvious it becomes that a well-designed built environment falls not on a continuum stretching from high art to vernacular building, but on a very different sort of continuum: somewhere between a crucial need and a basic human right.