Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the state decided it needed to find a way to calculate how many people lived in the United Kingdom. The Government’s main motivation was the prospect of invasion during the Napoleonic Wars and the need to know how many men were available to fight. The result was the first official census of 1801, which found that the population of the UK was nine million (the latest census in 2011 recorded 56.1 million). The census was not universally welcomed. In an echo of many of the debates we have today over civil liberties, there were those who believed such an act was the sign of an over-mighty executive, an infringement on human liberty and the right of man to live his life free from the beady eye of the state. That argument was lost and there has been a census every decade since (apart from 1941 when it was suspended for the Second World War).

* * *

The first four censuses of 1801, 1811, 1821 and 1831 are of minimal use to a family historian. They were, in the main, simple head counts, and those records that survive offer limited genealogical detail. There are some surviving records from the 1821 and 1831 censuses in certain regions which do offer more information, rather than merely how many people lived in a certain house, village or town. This was often done at the whim of the enumerator collecting the information, who knew the people he was ‘counting’ and decided to add some of their details.

A far more informative census, at least for genealogical purposes, started in 1841, when it was taken over by the General Register Office. From then on each census has listed the names of each person in every household in Britain. In 1851, the enumerators started to note the ages of those they recorded, making it an even more invaluable resource because it gives genealogists the opportunity to trace their ancestors even further back in time.

Here are some points to note about the census before we look at what information is available, where we can find it and how we can use it:

The 1841 census took place on 6 June 1841 and is generally referred to as the first ‘modern census’. The information it provides is:

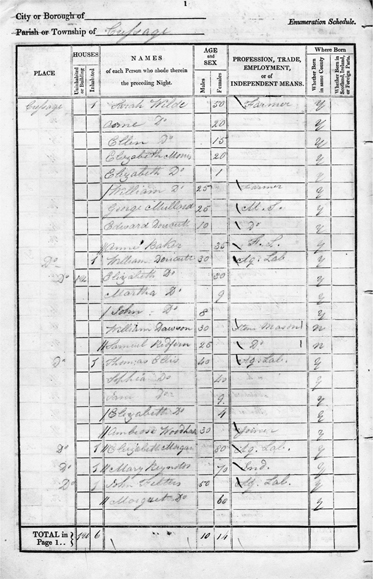

Census page for Sunderland

East, Durham, 1851.

Ag. Lab. – Agricultural labourer

Ap. – Apprentice

Cl. – Clerk

FS. – Female servant

H.P. – Member of HM armed forces on half-pay

Ind. – People with independent means

J. – Journeyman

M. – Manufacturer

MS. – Male servant

Census page for Bickenhall,

Somerset, 1851.

Enumerator’s signatures.

These censuses record similar types of information, with only a few differences (which are mentioned below) and for that reason can be grouped together.

The wealth of information available on a census return means it is possible to work out someone’s story just from glancing at the return, and it also provides a starting point for hunting down certificates. Take a 1911 return, for example: you can discover the date someone was married, how soon after marriage they had children, how far apart their children were born, while the place of their and their children’s birth will tell you how much or how little they had moved around. Their jobs give a fascinating glimpse into their lives, and by tracking them across various returns you can start forming a narrative of their life. Perhaps an ancestor started as a factory worker but gradually became a clerk and made the progression from blue to white collar. Also, by tracing your family back through census returns to 1841, if possible, you will gather the information and biographical detail you need to search for them before 1837 in the era of civil registration in parish registers.

It is also worth checking out your ancestor’s neighbours. What sort of people lived in the adjoining houses? How many people lived there and what jobs did they do? It will give you a glimpse into the conditions they lived in. My father’s family were coal miners and lived in coal-mining communities, sometimes 12 to a house. According to the 1881 census, my great-grandfather was working down the pit when he was 12 years old. Details like this can offer a real insight into the lives and hardships of your ancestors. You might also wish to see whether the houses your ancestors lived in are still standing. Visiting these places can be fascinating, and occasionally very moving. During series two of Who Do You Think You Are? Jeremy Paxman saw the tenement, then abandoned, where his single-mother ancestor was forced to raise her family in abject and unsanitary conditions. The experience was humbling and emotional for Jeremy. ‘We just don’t know we’re born, do we?’ he told the camera once he had recovered his composure.

The census can help you track your family and its ebb and flow through time. Through Scottish census records, the Who Do You Think You Are? team were able to build an extensive timeline of newsreader Fiona Bruce’s family. These records showed the movements of the Bruce family around Hopeman, a seaside village in Scotland that Fiona believed to be the family’s ancestral home, and allowed her to tour the village’s streets and see the houses where her ancestors lived. They also enabled the researchers to trace several generations further back and find the first Bruce in Hopeman, George Bruce, Fiona’s great-great-great-grandfather.

The census is vital for narrowing the search for birth, marriage and death certificates. For example, if you are looking for your great-grandparents’ wedding certificate and you know your grandfather was born in 1909, you would ordinarily start searching back from that date. But if you were to examine the 1911 census and find out that he was the youngest of four children, the oldest of whom was ten in 1911, then you can start searching backwards from 1901, rather than 1909, and save yourself a great deal of work. Likewise, if you don’t know when an ancestor died, rather than searching a wide range of dates for a death certificate, you can pinpoint the last census in which they appeared and begin your search from that date. Bill Oddie discovered in the 1901 census that his grandfather, Wilkinson Oddie, was listed as a widower. His oldest daughter Betsy was 12 and his youngest daughter Mary was seven. Armed with this information, Bill was able to track down a marriage certificate for Wilkinson and his wife, Cecilia, prior to 1889, and search for a death certificate for Cecilia between 1894 and 1901. He discovered that Cecilia died in 1897 during childbirth.

Census returns can also help you overcome any problems you might have locating civil registration records or tracking down that elusive ancestor. My great-grandfather Thomas Waddell and his wife, Maria, did not appear on the 1901 census, even though I had been told they were married by then. However, I hadn’t been able to find a marriage certificate, even though I had birth and death certificates for them both. I had tried every single spelling of the surname Waddell I could think of with no luck. It felt like a dead end.

But I didn’t give up. I went back to the 1881 census and there I found a Thomas Waddle who fitted all the details of the man I was looking for. He was living with a couple named William and Mary Wilson, as well as three children with the surname Waddle and three others named Wilson. They were of a similar age. His birth certificate had named his father as William Waddell and his mother Mary Waddell. What had happened?

I soon worked it out, with the aid of some death and marriage certificates. William Waddell had died in 1871, only a few months after Thomas was born. In 1874 Mary had married William Wilson, a widower, who also had children from his previous marriage. This was all very informative but it didn’t tell me why Thomas had disappeared from the 1901 census. But the name on the 1881 census, Waddle (not Waddell as on his birth certificate) had given me a clue. I looked through the marriage indexes in the 1890s under Waddle and then under Weddle. At last I struck gold. A Thomas Weddle had married a Maria Harrison (which I knew to be my great-grandmother’s maiden name) in 1895. I went to the 1901 census and there was Thomas Weddle, his wife and all the little Weddles. Not only had the 1881 census given me the clues to overcome the obstacle that had blocked my research, but in doing so I had learned a great deal about my great-grandfather’s upbringing, the tragic loss of my great-great-grandfather and the existence of a previously unknown man, William Wilson, who raised Thomas as a son. The revelation in the 1881 census that my great-grandfather had a step-family also gave me a whole new chapter to explore in the future.

Most local and county record offices have microfilmed copies of each census from 1841 to 1901, but not 1911. So do the Family History Centres operated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (these are worldwide – to find the nearest one visit https://familysearch.org/locations/centerlocator). The National Archives in Kew (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk) has returns from 1841 to 1911 online, available free of charge.

There are a host of websites that offer searchable indexes and have scanned original returns, but most of them charge a fee. Here are some of the options to consider.

The Scottish census was taken in the same years as its English equivalent and it features much of the same information. The returns can be searched at www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk for a fee, while some regions are available to search for free at www.freecen.org.uk.

Ireland did not start taking a census until 1821. As mentioned above, many of these records were destroyed during the Irish Civil War of 1922–3 and very few of the nineteenth-century records survive. The 1901 and 1911 censuses are available on the ancestry.co.uk website for a fee, but are also available at www.census.nationalarchives.ie for free. The good news is that they feature some additional information, too. The 1901 census reveals the religious denomination of your ancestors as well as the condition of their house! The 1911 census, like its English counterpart, reveals how long your ancestors had been married and the number of living children their marriage had borne. As Ireland was a united country at this point, these censuses also cover the counties that would later form Northern Ireland.

Sometimes it can be tricky tracking our ancestors down on the census. Perhaps they’re not where you expect them to be and occasionally you might not be able to locate them at all. Here are some common reasons why you can’t find your ancestors and some tips on how to overcome them: