With a few exceptions, the British have always been a welcoming group. Despite recent hysterical newspaper reports warning of ‘floods’ of immigrants coming to despoil our green and pleasant land, the truth is that migrants have made their way here for centuries, either fleeing from war and persecution or looking for a better life for themselves and their families. Many of us will encounter migrant ancestors as we journey through our family’s past, uncovering some fascinating and moving stories in the process.

* * *

In fact, our attitude towards immigrants was so liberal that before the nineteenth century it is relatively difficult to track our immigrant ancestors. Unlike other nations, we didn’t ask those coming here to register on arrival. There is no equivalent to the United States’ Ellis Island, where new arrivals were processed and checked – but this means a scant paper trail for us. The first clue our immigrant ancestors might leave is on a census return, stating their place of birth. So how do you go about researching them?

Let’s take the 1851 census, for example. It reveals that almost a quarter of Liverpool’s population was born in Ireland. Why so many? To understand this, and most other immigration stories, it’s worth trying to learn what was happening in the world at the time, particularly in the place of your ancestor’s birth. In this case, Ireland was ravaged by the Great Famine. Men, women and children were starving and left their homeland in search of work, food and survival. Liverpool is just a short journey across the Irish Sea, so it became the most popular port. Other groups who came to England in the nineteenth century include Jews fleeing the pogroms of the Russian Empire in the later decades, and Germans escaping the upheavals in their homeland during the middle of the century.

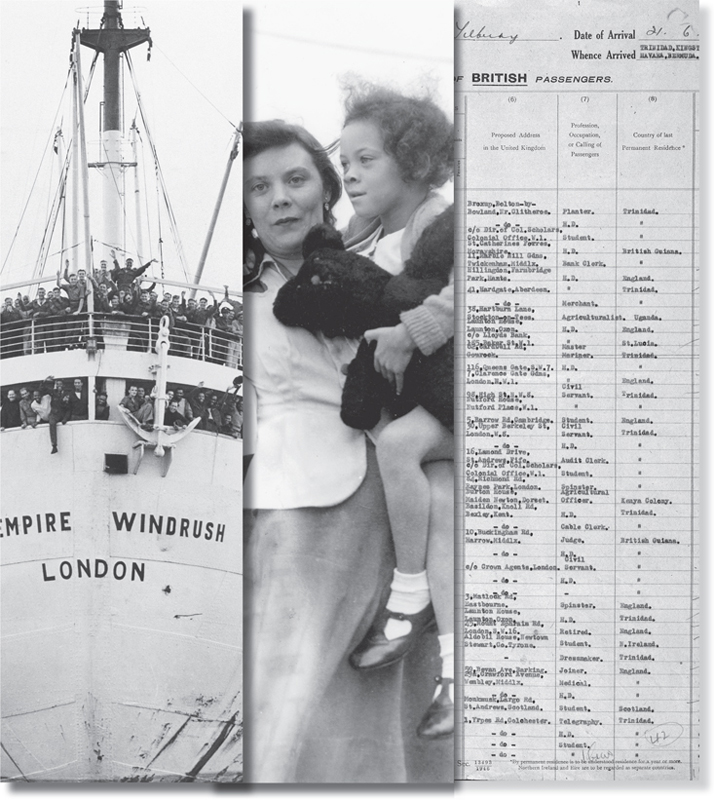

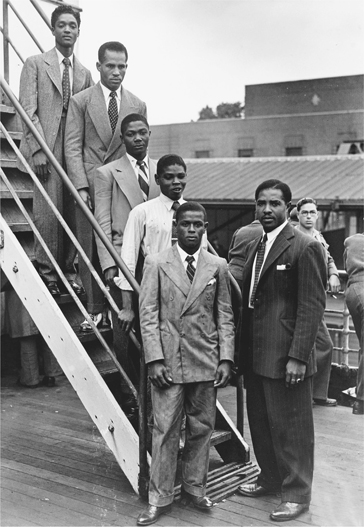

Jamaican immigrants on board the ex-troopship,

Empire Windrush at Tilbury, 1948.

The best starting point in your search for any immigrant ancestors is within your family. They might be able to provide you with the background details you need to further your search. There might also be some documents, diaries, letters, or even something as a precious as a ticket or boarding pass to identify how they reached these shores. The actor David Suchet always suspected that his father’s line had Eastern European origins. His older brother John told him that their father, Jack, had once opened up to him, explaining that the family had changed their name to Suchet when they were living in South Africa. He remembered his father said he originally came from small town in Lithuania, then part of East Prussia.

David then turned to his extended family in South Africa for more help. This is another excellent research path to follow. Email and Skype have made the world a much smaller place, and contacting distant relatives in far-off lands has never been easier or cheaper. David learned that his great-grandparents were called Jacob and Beila Suchedowitz – the family name until his father changed it, which gave him the information he needed to start unravelling the mystery of where his father’s family originated.

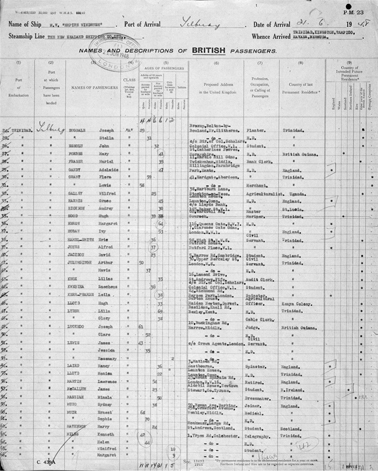

So the rule is: start at home, gather as much information as you can and then look at birth, marriage and death certificates and census returns to try and pinpoint the moment your ancestor arrived in this country. Then a good source of information is the passenger lists from 1878 to 1960 (although many pre-1890 were destroyed). These are available online at www.ancestry.co.uk. For further information, it is also worth consulting the National Archives’ online guide to other immigrant records in its collection at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/looking-for-person/immigrants.htm.

Another useful resource for family historians are denization and naturalization records. After arriving, if they wished to become British citizens, migrants had two choices: naturalization, which offered more rights but was more expensive, or denization, which many people chose because it was cheaper, even though it meant they had no right to vote. But there were also many immigrants who chose neither option and never became British citizens. For those who did, the records are at the National Archives. You can find more information and search naturalization case papers online at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/looking-for-person/naturalised-britons.htm.

The website www.jewishgen.org has free, easy-to-use databases that can help your research, sourced from across the world. There’s also the opportunity to link up with other family researchers who might have researched the same information you’re looking for, and a discussion group where you can ask questions, swap tips and focus on specific geographic areas. It’s also worth visiting the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain’s website (www.jgsgb.org.uk).

The years between 1948 and 1962 saw an increase in immigration from Commonwealth countries, in part to address the labour shortage after the Second World War and the desire of migrants to seek a better quality of life. There were few restrictions in that period and the vast majority of migrants came from the Caribbean and the Indian sub-continent. People like athlete Colin Jackson’s grandfather, who left Jamaica for the cold of Cardiff in 1955 in search of work. He brought his children with him, but left his wife, Maria, behind so she could nurse her sick father while he raised his children single-handedly in a strange country.

Quality and access to records can vary by country, so for first-, second- and third-generation immigrants it is crucial to speak to your family and learn as much as possible from them if you can. There are few available records from 1960 onwards. From those who journeyed here, their relatives and friends, even the people they left behind back home, you will be able to learn about their stories and uncover further avenues for research, as well as find vital documents and memorabilia. For more stories, case histories and background, as well as valuable advice on tracing your roots, consult www.movinghere.org.uk (it also has information about Jewish and Irish as well as Caribbean and South Asian migrants). Sadly, since 2013, the website is no longer being updated but it remains a wonderful resource for those in search of their immigrant roots.

For those tracing their roots in the West Indies, the National Archives has Colonial Office Records, copies of censuses taken in the West Indies, military records, government gazettes, wills, court cases, registers of slaves, and much more. An excellent place to start is the Tracing Your Caribbean Ancestors by Guy Grannum (Bloomsbury, 2012).

Tracing Your British Indian Ancestors by Emma Jolly (Pen & Sword Family History, 2012) is a good launching pad for those seeking to find more about their Indian roots. It gives an exhaustive guide to the resources you can find in various archives. How far back you’ll be able to trace your family ancestry in India depends on several factors: how much information you have about your family origins and your family’s religious denomination. It’s unlikely you’ll be able to find any information online, although it’s always worth trying www.familysearch.org.

Just as immigrants have been making this country their home for centuries, so people have emigrated in search of new lives elsewhere. In the nineteenth century alone it’s estimated that ten million people left Britain. The most popular destinations were the United States and the new-found colonies, including Canada and Australia. The ancestors of Jodie Kidd were among the early settlers in New England, while Jason Donovan’s forebears took a less voluntary route to Australia…

Passenger list for the SS

Empire Windrush, 1948.

The best place to start your search for emigrant ancestors is in the country they chose as their new home. For example, if they emigrated to the United States they might have passed through and been processed at Ellis Island, and you can search for their names on the database www.ellisisland.org, which covers the period between 1892 and 1924. The website ancestry.co.uk has a number of US passenger lists, all fully searchable by name. Closer to home, findmypast.co.uk has a database of outbound passenger lists from the UK between 1890 and 1960.

Our ancestors might also have lived and worked abroad, perhaps for the British Empire in one of its colonies. The impressionist and comedian Alistair McGowan was always curious about his family’s bloodline, in particular whether there was any Indian ancestry in the mix. Research revealed that generations of McGowans had been born in India, working for the Raj and the East India Company, dating back to 1775. With the assistance of a local historian, Alistair found a reference to a gloriously named ancestor, Suetonius McGowan. He learned that Suetonius married a noble Muslim lady, whose name was omitted from the baptism record because she refused to convert to Christianity. The mystery was solved: here was the Indian link that Alistair McGowan suspected he would find.

The British Library is the custodian of the records of baptisms, marriages and burials of those who worked in the East India Company or the India Office. The African and Asian Studies Reading Room there holds the largest UK-based collection of India Office Records. Alongside this collection researchers can also look for their ancestors among church, company and civil records. Guidance can be find on the British Library’s ‘India Office Family History’ webpage. Many of these records are now available to search online at findmypast.co.uk, along with millions of other military and civil records, including pensions and wills.

Immigrants from Jamaica arrive at Tilbury, London,

on board the empire Windrush, 1948. The party are

five young boxers and their manager.