Chakra Medicine Practices

eastern methods

An ounce of practice is worth more than tons of preaching.

Mahatma Gandhi

So far we’ve been delving into Western chakra medicine practices, which are, for the most part, fairly straightforward. Eastern processes offer an additional salting of spiritual practices. When blended with physical practices, these draw on the historical power of chakra medicine to clear and balance our chakras and ourselves. If you want to explore the origins of Eastern chakra work, a history of chakraology is available in Part 4 and can provide additional insight into these often ancient techniques.

The Yamas and Niyamas: The Importance of Living a Clean Life

Thousands of years ago a man named Patanjali presented eight rungs, or “limbs,” of yoga that the yogi must practice to achieve enlightenment. The first two rungs on the ladder to the heavens are the yamas and niyamas. While we begin our discussion of these principles in the Hindu tradition, the yamas and niyamas are universal ideas that cut across cultures, religions, gender, and ethnicity. In many ways they lay the foundation for all the practices in this book.

The Five Yamas

There are five yamas, which can be thought of as codes of self-regulation that guide our interaction with the external world. Briefly, they are:

Ahimsa: Nonviolence

Asteya: Not stealing

Satya: Honesty

Brahmacharya: The practice of seeking the presence of God, or conduct worthy of one who seeks to know Brahman

Aparigraha: Nongrasping, nonpossessiveness

As you shall discover, many of the practices in this chapter serve to support us in practicing the yamas. We take a deep breath when we’re irritated so we may hold our temper; we clear our chakras so we may honestly address our blockages and imbalances; we eat mindfully to contemplate the continual presence of Spirit; and we practice mudras to foster the state of aparigraha.

The Niyamas

There are five niyama principles as well. These balance the outward-focused yamas in that they serve as practices for the internal training of the self and the cultivation of positive virtues. They are as follows:

Shaucha: Purity of body and mind

Santosha: Contentment

Tapah: Training of the senses; austerity

Svadhyaya: Self-study, reflecting on sacred words

Ishvara Pranidhana: Surrender to God1

Here we find the underlying reasons for further chakra medicine practices. Eating healthy food, using gemstones, and washing our chakras with color are all ways to practice shaucha. What are we aiming for when we create yantras or mantras but svadhyaya, reflection on the sacred? What are we ultimately seeking to achieve through all our aims but ishvara pranidhana?

In all of these ways we are called to follow our path toward a life immersed in love. And many believe this journey begins with—and is completed through—sacred breathing, or pranayama.

Pranayama: The Breath of Spirit

Sprinkled throughout this book are breathing practices related to specific chakras or chakra systems. Breathing has been key to the process of enlightenment since the dawn of chakraology. Because I cannot overstate the importance of breathing in chakra medicine, this section features a variety of additional practices.

In fact, Yogi Bhajan suggests that pranayama is the most creative activity God designed for humankind: from breath comes life. As we’ve been exploring throughout this book, the core of pranayama, the practice of breathing, is prana, the vital force, or energy, of the universe. Prana is itself a subtle energy, and the breath is the external manifestation of it. Spiritually oriented breathwork, therefore, directs cosmic energies through our respiratory system, which also benefits our health. The air sacs in our lungs, if unfolded, would cover 1,404,000 square feet. Think of the ripple effects of filling them with breath! Proper breathing also cultivates kundalini energy, clears and balances our chakras, and regulates energy flow through our 72,000-plus nadis. How could pranayama not benefit body, mind, and soul? To connect through breath to the divine light is to link directly to the Divine.

Breathing exercises differ according to yoga modalities and cultural perspectives. Kundalini yoga practitioners often combine pranayama activities with mantras and mudras, while Hatha yoga afficionados merge postures with breathing.2 Specific pranayama practices are performed daily in Ashtanga and Bikram yoga, while in other traditions one selects from practices as needed.3

Breathing is also important in spiritual traditions of the West. Certain Christian denominations practice centering prayer, which uses breathwork, and various types of Jewish meditation emphasize breathwork to enable followers to find their own prophetic voice.4

Contemporary research is proving that yoga practices, of which pranayama is a vital component, are effective tools for preventing and managing disease. Yoga reduces stress and anxiety, triggers life-enhancing neurohormonal mechanisms, and can even benefit cancer patients. It increases feelings of well-being, alleviates hypertension, and helps manage weight. Pranayama in particular oxygenates our bodies, cleanses our lymph system, strengthens our immune system, bathes our cells in nutrients, and alleviates our “flight, fight, or freeze” responses.5

Breathing is particularly important today because we receive less oxygen from the air in modern times than we did hundreds of years ago. Infections and physical and emotional stress deplete the available oxygen in our bodies. Toxic stress resulting from environmental chemicals requires more oxygen, not less, to enable detoxification. Unfortunately, there are fewer trees in the world and a lot more carbon dioxide, reducing our available atmospheric oxygen.6 All these reasons add up to the importance of an intentional and regular practice of pranayama.

Pranayama can be as simple as taking full, slow, and deep breaths through the nose and concentrating on inhalation, exhalation, and the pause in between. With this focus on the breath, experts suggest making the exhalation longer than the inhalation; this soothes the main organs located in the abdominal cavity and circulates our cleansing fluids, including the lymph. It also more completely empties the bottom third of the lungs, where toxins can accumulate. Long-term practice of this technique infuses the bottom of the lungs with nourishing breath after the cleansing has occurred. It also breaks up the unconscious regulation of breathing and, subsequently, unconscious emotional patterns.

Inhaling through the nose filters, warms, and moistens the air, assuring an efficient transfer of oxygen and carbon dioxide. And breathing to the pause point teaches us that we can self-regulate in all areas of our life, not only in our breathing. We gain awareness of the connection between our choices and their consequences. As we more fully activate our energetic anatomy, we develop spiritual awareness and balance. We develop ourselves.7

There are thousands of different types of pranayama, with about fifty different breathing practices described in the ancient spiritual Hindu texts known as the Vedas alone. Besides the three main aspects of pranayama—inhalation, exhalation, and retention—there are traditional guidelines related to place, time, and number of breaths. These rules can be quite specific. Those related to place, for example, include practicing breathwork in a sacred, undisturbed location, and they go on to recommend sitting on kusa grass and deerskin near a reservoir with no snakes or animals nearby. The recommended times for a specific practice might be at the beginning or end of winter, and one might chant a bija (seed syllable) mantra sixteen times while inhaling, then retain the air while chanting up to sixty-four times.8

Fortunately for us, modern practices, while based on ancient ones, are less complex than this, yet common guidelines still apply. Many believe it is best to practice pranayama on an empty stomach, for example.

Following are several of the most accessible forms of pranayama, described with their positive benefits. For meditative sitting poses that support the practice of many of these exercises, see “Poses for Seated Meditation” on page 241.

- • Sit comfortably.

- • Inhale slowly and deeply through both nostrils.

- • Hold your breath as long as you can.

- • Exhale slowly, contracting the air passageways in your throat and making an audible whispering sound, sometimes also described as a “rushing” or “ocean” sound.

This is one round of ujjayi breath, which I recommend mainly for clearing and easing your fifth chakra. It will strengthen your vocal cords, stimulate the thyroid, improve blood circulation, and ease lung, chest, and throat tension. Do not practice ujjayi breathing if you have heart problems.9

- • Sit in a meditative position.

- • With your back straight, relax your shoulders and close your eyes.

- • Close both of your ears with your index fingers.

- • Raise your elbows to shoulder level to the side.

- • Inhale deeply.

- • Hold your breath as long as you can.

- • Exhale slowly while making the sound of the letter M—m-m-m-m-m—resembling the buzzing sound of a bee.

Bhramari calms and relaxes, relieves stress, increases concentration, and strengthens your vocal cords; therefore, it is ideal for cleansing your fifth chakra and is also supportive of the sixth chakra. It is traditionally best practiced at night or in the early morning.10

- • Sit in a meditative position.

- • Straighten your back and relax your shoulders.

- • Close your right nostril with your right thumb and raise your right elbow to the level of your right shoulder in the front.

- • Close your eyes. Now inhale and exhale through your left nostril, first slowly, and then a little faster.

- • Repeat the previous step between twenty and twenty-five times.

- • Take a long breath, drawing from your belly, and hold it as long as you can.

- • Repeat the entire round by closing your left nostril and breathing through your right.

Bhastrika aids detoxification and weight loss, enhances digestion, regulates the nervous system, and acts as a blood purifier. You should avoid it if you have high blood pressure, a hernia, or heart and lung problems. Because it draws breath up through the belly, it is beneficial for your third chakra and is also used to advance the sixth chakra. If you have a chronic illness or lack stamina, do not do bhastrika frequently.11

Exercise: Anulom Vilom (Alternate Nostril Breathing)

- • Sit in a meditative pose. When practicing this pranayama, you will breathe into your chest and not your belly.

- • Use your right thumb to close your right nostril.

- • Inhale through your left nostril.

- • Close your left nostril with your right hand’s index and middle fingers.

- • Exhale through your right nostril.

- • Inhale through your right nostril.

- • Close your right nostril with your right thumb.

- • Exhale through your left nostril.

This exercise balances all your chakras, normalizes your body temperature, relieves stress, cleans the nadis, improves circulation, and has anti-aging effects.12 You may begin with five rounds of anulom vilom daily and increase the number of rounds as your capacity grows.13

- • Breathe in deeply through your nose. Feel your diaphragm moving down, allowing your lungs to expand and forcing your abdomen out. Continue inhaling until your chest expands and your collarbones rise.

- • Exhale slowly while chanting om for about twenty seconds. Keep the “o” long and the “m” short.

- • You can repeat this cycle three times.

The udgeeth practice is helpful for relieving insomnia and depression and increasing concentration. It clears the fourth chakra and can pull energy up through all the chakras. And with this practice you are singing with the earth, whose own vibration is believed to resonate with om.14

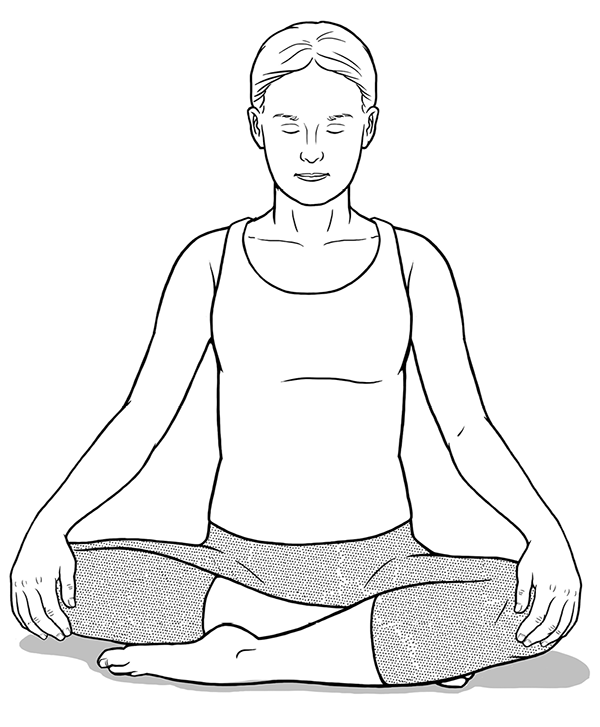

Also called the easy, decent, or pleasant pose, this asana (pose)—which is practiced in yoga, Buddhism, and Hinduism—is similar to sitting in a cross-legged position. Here is how to perform Sukhasana; see Illustration 17 for tips.

- • Use one or two folded blankets or a mat to create a flat base. Sit on this base.

- • Sitting close to one end of the base, stretch your legs in front of you.

- • Cross your shins and open your knees wide.

- • Slip each foot beneath the opposite knee and fold your legs toward your torso.

- • Keep your feet relaxed and make sure the outer edges of your feet rest on the floor and the inner arches are below the opposite shins.

- • Ensure that you are in a neutral position by pressing your hands against the floor and lifting your seat bones. If you can, hang like that for a breath or two and then slowly lower yourself to the ground.

- • Put your hands on your knees, palms down, and imagine your tailbone sinking into the floor.

- • You can change leg positions when you need to.

- • If you are having difficulty remaining in this position, you can sit with your back against a wall for support.

Avoid this posture if it produces pain or if you have knee, ankle, hip, or spine injuries. This exercise produces serenity, reduces stress, broadens your collarbones and chest, lengthens your spine, promotes alignment, reduces fatigue, and stretches your legs, ankles, and knees.15

This pose is also called Kamalasana, or the “lotus position,” because the legs appear to form a lotus flower. This pose can be challenging for many people. Never force yourself into a challenging pose; instead, use an easier pose like Sukhasana or simply sit straight in a chair. You can also slowly work your way into these and other more difficult poses using Illustration 18 as a guide.

- • Sit on the ground and extend your legs forward.

- • Put your right foot on your left thigh and your left foot on your right thigh.

- • Place your hands on your knees, palms up.

- • Keep your spine straight and your head erect.

- • Close your eyes.

This pose is considered ideal for pranayama. It improves concentration, assists with the flow of vital fluids, prevents abdominal and female reproductive issues, and encourages peace and longevity.16

Mudras: Signs of the Soul

Mudras are movements or gestures that create psychic powers and spiritual emotions. Pranayama and other spiritual practices are often accompanied by mudras; in fact, many mudras combine asanas, pranayama, and one or more bandhas into one integrated activity. Mudras can also be stand-alone exercises.

When we consciously form a mudra it affects our subconscious, enabling an ever-increasing awareness of the flow of vital energy throughout our energetic system. Promoting physical health, mudras ultimately awaken and attune our chakras.

Mudras not only encompass a symbolic activity or gesture but can also involve pratyahara: withdrawal from the physical senses. When all is silent, our true self sometimes speaks the loudest, albeit without words. As you shall see in this section, mudras can involve shifts in facial features or other parts of the body. Most mudras, however, whether “loud” or “quiet,” employ the fingers.

In many cultural systems different fingers represent different energies, so selecting the fingers to form into a mudra is meaningful. In the traditional Indian system, the fingers hold the following meanings:

Thumb: Paramatma, or the Supreme Consciousness

Index Finger: Our jivatman, or individual soul

Middle Finger: Sattva, or purity

Ring Finger: Rajas, or passion

Little Finger: Tamas, or inertia

Touching the index finger and thumb together, a configuration common to many mudras, represents the union of the individual soul and the Supreme.17

Following are a few of the basic mudras:

Exercise: Jnana and the Chin Mudras

The jnana mudra (jnana means “knowledge”) can be maintained for the duration of a pose and is accomplished this way:

- • Sit in a meditation asana and bend the index finger of each hand. Let the tip touch the inside of your thumb, at the root. (In some systems, you touch the tip of your index finger with the tip of your thumb.) Keep your other three fingers straight.

- • Place your hands on your knees, palms turned down.

- • Make sure your three straight fingers and the thumb of each hand point toward the floor.

The steps to chin mudra are the same as the jnana mudra except you rest your hands with the palms facing up; the mudra can be seen below.

Both mudras empower any asanas they accompany, and, according to Dr. Hiroshi Motoyama, they also accomplish so much more. Combining TCM and chakra knowledge, Motoyama explains that prana (or chi) absorbed through manipura is sent into the lungs, from which it flows through the lung meridians into the thumbs. Some of the prana fills the “well” points on the tips of the thumbs. When the index finger touches the thumb in jnana and chin mudras, the energy that would normally be discharged from the body is instead sent to the large intestine meridian, which starts at the tip of the index finger. This preserves bodily vitality and allows one to sustain meditation for a longer time.18

Also called eyebrow-center gazing, this mudra involves gazing forward at a fixed point before moving your eyes as far upward as possible, all the while keeping your head stable. Next, focus your eyes at a spot between your eyebrows and concentrate on that point. Ideally you will do this while sitting in a meditation pose with your hands in jnana or chin mudra. In this position, concentrate on the connection between your individual self and the Supreme Consciousness for as long as you can.

This practice is highly regarded in yoga and enables the transcendence of the mind and ego, matched with an ever-increasing awareness of all things spiritual. This mudra is also ideal for awakening the ajña chakra, removing tension and anger, and strengthening the eyes.19

Called the horse mudra, ashvini mudra involves the following steps:

- • Sitting in a meditation asana, relax your body, close your eyes, and breathe normally.

- • Contract your anal sphincter muscles for a few seconds and then relax them. Repeat this activity a few times.

- • If you feel comfortable, contract your anus while inhaling. Hold your breath and then contract, and when you exhale release the contraction. Repeat this practice for as long as is comfortable.

This mudra is particularly beneficial for the first chakra, initiating control of the sphincter muscles while preventing prana from escaping the body. The resulting conservation of energy enables the climb of the kundalini. This mudra is particularly helpful for anyone suffering from anal, rectal, or uterine issues, as well as constipation. It is a helpful preparation for the mula bandha featured in this chapter.

Known as the mudra of the nine gates, this practice frequently accompanies the mula and vajroli mudras. It is important because it works with the nine bodily openings through which we sense the physical world.

For this mudra, you use your fingers to close these gates in the temple of the body so your spirit can pass through the tenth gate—an energetic one—into sahasrara and the gate of Brahma. The mudra can be seen in the illustration below. The steps are as follows:

- • In a meditation position, relax your body and inhale slowly and deeply. Now concentrate on each chakra for a few seconds.

- • Cover your ears with your thumbs.

- • Cover your eyes with your index fingers.

- • Pinch your nostrils with your middle fingers.

- • Press your lips together with your ring finger just above your top lip and your little finger below your lower lip.

- • Breathe in and out slowly.20

Eleven Buddhist Mudras to Accomplish Any Goal

In Buddhism we find eleven mudras that compose the full range of energetic goals:21

Exercise: Dhyani Mudra (also called Samadhi Mudra)

Rest the back of your right hand on the palm of your left hand, lightly touching the tips of your thumbs together. Let your hands rest in your lap.

This mudra promotes deep meditation and cleanses energetic impurities.22

With your palms facing forward in front of your body, point your right hand upward at shoulder level and your left hand downward at hip level, with the thumbs and index fingers of both hands forming a circle. Extend your fingers as shown in the image. This mudra transmits teachings.23

Turn your left palm toward your body and your right palm away from it. Create a circle by touching the thumbs and index fingers of one hand to the other. This mudra evokes the wheel of dharma, or cosmic order.24

With your left hand resting palm up on your lap, let your right hand hang over your knee, palm downward. Also called “Touching the Earth,” this mudra depicts the hand gestures the Buddha made upon achieving enlightenment.25

Raise your right hand to shoulder height with your fingers extended, wrist bent, and palm forward. This mudra creates fearlessness and provides protection.26

Extend your right hand forward, palm out and fingers pointed down. This “boon-granting mudra” bestows the energy of compassion and liberation.27

Raise both hands to your chest, also raising your index fingers, which should touch each other. Cross your other fingers and fold them down. Your thumbs can touch at the tips or be crossed and folded, as you can see in the illustration. This is the mudra of enlightenment.28

Exercise: Mudra of Supreme Wisdom

Grasp your right index finger with all the fingers of your left hand to encourage access to divine wisdom and the realization of unity.29

Exercise: Anjali Mudra (also called Namaskara Mudra)

Place your palms together at your chest. With this mudra you greet the Divine in everyone.30

Cross the fingertips of both of your hands. Many practitioners recommend setting your joined hands upon your heart. This mudra grants unshakeable confidence.31

Hold up your right hand at shoulder level, and touch your middle finger and thumb. Keep your ring finger next to your middle finger and slightly raise your little and index fingers. This mudra wards off evil.32

Making Use of the Eyes

As you have noticed, mudras may involve the eyes, a special focus in chakra medicine. The eyes play a special role in the journey of enlightenment, in addition to being a critical organ related to the physical body and the sixth chakra. Not only do our eyes enable us to see reality, but they also enable us to see through it—sometimes right into the heavens.

Secret of the Golden Flower

One of the most fascinating treatises about the spiritual nature of the eyes is called Secret of the Golden Flower.33 This esoteric knowledge was passed down orally for centuries before being written down on wooden tablets in the eight century ce and then later recorded by Lu Yen, a Taoist adept and leader of the Religion of Light. It is a unique window into spirituality in that it embraces several ancient paths. Rooted in the Persian Zarathustra tradition (Zoroastrianism), it also has origins in Egyptian Hermeticism and features ideas found in Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and even elements of Christianity.

At its heart, this manuscript outlines a path toward illumination that is centered on silent meditation techniques and the circulation of the essential breath energy. It features an approach originally taught at the beginning of “form,” or manifested reality, when people knew how to use the powers of heaven. The eyes play a critical role in the method this scripture presents; in order to “circulate light,” the practitioner cultivates the appearance of a bright image in front of the midpoint between the eyes. This image is called mandala, original essence, golden flower, and original light.

The eyes are considered of such importance because they can receive our negative thoughts, hence operating as a secret “heavenly heart.” In this guise, the two eyes represent the sun and moon. A practitioner who can perceive this light fully passes through the gate and can start embodying the immortal essence.34

In my reading of “The Secret of the Golden Flower,” I perceive the following steps to activating the eyes:

- • Sit in an upright and comfortable position.

- • Sink your eyelids halfway so as to look down your nose. In Taoism, this guiding line is called the “yellow middle”; in Buddhism, the “center in the midst of conditions.” In this practice, the guiding line is the point exactly between your eyes, although this is only a symbolic representation of the light available anywhere and everywhere.

- • Allow the light to stream into the eyes without forcing it.

- • Suspend your thoughts, letting yourself forget all your concerns.

- • Allow the light to shift downward.

If the light doesn’t seem to be entering your eyes or circulating through your body, listen to your breath until it stops sounding ragged or rough. As it is said, “When the heart is light, the breathing is light.”35

Trataka

Another process for cultivating the power of the eyes is a Buddhist one called trataka, or eye gazing. This method stimulates ajña, although some sources also maintain that it opens the pineal gland. Moreover, it bolsters our ability to concentrate and therefore strengthens meditation.

There are two types of trataka. One is an outer practice called bahiranga and the other is antaranga, an inner practice. In bahiranga, the focus is on an object, dot, or person outside of yourself. In antaranga, inner visualization is the key; for instance, you can perform antaranga by imagining your chakras. Either form of trataka can be conducted for fifteen minutes or so.

A simple way to perform outer trataka is to sit in a darkened room in a comfortable meditative position. Place a lit candle about two feet away, positioning it at eye level. Close your eyes and relax, making sure to keep your spine long but not stiff. Once you are fully comfortable, become still, open your eyes, and gaze at the brightest spot of the flame. Close your eyes if they become tired or the image blurs, but continue to see the afterglow image that remains. When this vision fades, open your eyes and stare at the candle again. The goal is to work up to peering at the flame for several minutes without blinking your eyes.

The practice is especially beneficial for people suffering for insomnia and mental disarray and can be done a few minutes before bedtime to help with these issues. Outer trakata can alleviate certain eye problems such as nearsightedness and clear the mind. One thought about its effectiveness is that the stomach and gallbladder meridians flow around the eyes. During trataka these meridians are stimulated, and the resulting calm is transmitted to the manipura chakra, the mental center.

Yogis practice trataka with many objects and even with people, such as gazing at the full moon or into the eyes of a beloved guru. These practices can be directed toward the development of psychic powers but should be undertaken under the watchful care of a teacher, as they can be misused.36

The Four Bandhas

The bandhas are yoga moves that help you regulate your internal systems, from endocrine to digestive. They stimulate your life energy and help release chakra and subtle energy blocks, inviting the flow of kundalini and prana. In Sanskrit, the word means to “lock,” “hold,” or “tighten,” and that’s the nature of these asanas. They are often accompanied by various mudras and coordinated with pranayama techniques.

There are three primary bandhas, which are frequently done as a sequence, and one that ties them all together. The simplest descriptions of these follow:

Mula means “root,” so this is the root lock. You can conduct the exercise while sitting, standing, or in an asana (pose). To perform it, contract the area between your anus and testes if you are a man; if you are a woman, contract the muscles at the base of your pelvic floor, behind your cervix, as if stopping urination while performing a Kegel exercise. The lock allows your energy to flow up your spine without leaking out. It is useful for the genital, excretory, and endocrine systems and pelvic nerves, and it relieves constipation and depression.

Uddiyana means to “fly up” or “rise up.” This bandha, therefore, allows your energy to move up into your abdomen, diaphragm, and stomach.

Practice this bandha by standing with your feet about three feet apart. Inhale through your nose and stretch your arms up along your ears. Exhale from your mouth and bend forward, placing your hands just above your knees. Without breathing, close your lips, straighten your elbows, and sense your abdominal wall and organs pushing toward your spine. Stay in this position for as long as you can, then exit by inhaling through your nose and standing up straight again. Raise your arms alongside your ears and exhale through your nose as you return your arms to your sides.

This practice is especially beneficial for anyone with abdominal or stomach ills. It also increases your metabolism and relieves stress and tension.

This bandha gives you permission to create a double chin. In Sanskrit, jal means “throat,” jalan means “net,” and dharan is “stream” or “flow.” This bhanda is a throat lock, and it helps you control the flow of energy through your neck.

Conduct this exercise by sitting up tall. You can cross your legs or rest your sitting bones on your heels. Place your hands palms down on your knees. Inhale through your nose and bring your chin toward your neck. Lift your sternum a little and then press your hands down and straighten your elbows. Push your chin down farther and hold this position for as long as you can. You can move your hands into mudra poses at this point, if you desire. To exit, lift your chin, inhale as fully as possible, and then exhale.

This bandha compresses your sinuses and can therefore help regulate your circulatory and respiratory systems. The pressure on your throat can boost your thyroid and metabolism. It is also an excellent practice for instantly alleviating stress and anger.

Maha means “great,” and that is the nature of this bandha, which combines the previous three locks.

To conduct this bandha, sit comfortably on your shins and put the palms of your hands on your thighs or knees. Inhale deeply through your nose and then exhale, also through your nose. Perform the mula bandha. Still squeezing, enter into the uddiyana bandha. Inhale, lift your chest, and enter the jalandhara bandha. Hold, pressing your palms down, for as long as you can. Exit by lifting your head, fully inhaling, and releasing all the bandhas. This combined bandha provides the benefits of all three individual components.37

Chakra-Focused Asanas

Asanas are a vital part of every yoga practice. Many asanas bolster one chakra more than another. Laura Barat, a Vedic astrologer and author, recommends specific asanas to rebalance specific chakras and open them to just the right flow of heavenly energy.38 They all come from Hatha yoga, a branch of yoga that cultivates the rising of kundalini for the achievement of enlightenment. Here I have selected one of the many asanas she recommends for each chakra.

Note that Barat’s system does not include a recommendation for the seventh chakra. This is fairly typical, as the seventh chakra is considered beyond the bounds of physicality. So instead I have featured a simple yogic pose that will boost your seventh chakra.

Exercise: First Chakra Pose: Virabhadrasana I (Warrior I)

Warrior poses create heat, open the hips, and strengthen the legs. This makes them wonderful first chakra exercises. Virabhadrasana I is an ideal pose for promoting confidence as well as boosting your first chakra.

- • Start in mountain pose, which involves standing straight, feet securely planted, legs together, back straight, and arms at your sides.

- • On an exhale, move your left foot back three to four feet behind you.

- • Turn your left foot in at a 45-degree angle and keep your right foot in front of you, toes pointing toward the front of your mat.

- • Put your hands on your hips and bend your right knee so your thigh runs parallel to the mat and your knee is aligned over your heel.

- • Root the outer edge of your left foot into your mat and rotate your hips and shoulders forward so your weight is on your bent right leg.

- • Inhale and extend your arms above your head, perpendicular to the ground. Keep them wide open as if reaching for the sky, shoulder-width apart and parallel to each other.

- • With your palms facing down, draw your shoulder blades down and away from your neck.

- • Exhale and contract your abdominal muscles, tilting your hips and tucking in your tailbone. Make sure your right knee is bent in a way that aligns it over your heel.

- • Continue to breathe, applying a bit more pressure on your right heel rather than the toes. This will stabilize your right knee and ease the knee joint. Imagine that your pubic bone is lifting toward your navel.

- • You can strengthen this pose by pressing your outer left heel into the floor; you will feel an uplifting energy moving up through your left leg, into your hips, and into your arms. Remain in this position for thirty seconds to one minute.

- • Throughout the duration of the pose, keep your neck loose and your head looking straight ahead; alternatively, tilt your head back to gaze at your thumbs.

- • To exit, exhale while lowering your arms and put your hands back on your hips. Inhale while pressing into your right heel and step your left foot forward. Exhale while taking your hands off your hips, adjust your feet, and return to mountain pose.

- • Take a few breaths and perform this pose with the opposite leg behind you for the same amount of time.

This first chakra pose strengthens your shoulders and arms, thighs and ankles, and back muscles. It expands your chest, increases stamina in your core muscles, improves balance, and stimulates your abdominal organs. Take caution if you have heart problems, high blood pressure, or balance problems. If you have shoulder pain, keep your hands open and arms parallel to avoid shoulder joint compression, and if you have discomfort in your neck, look forward and keep your chin parallel to the ground.39

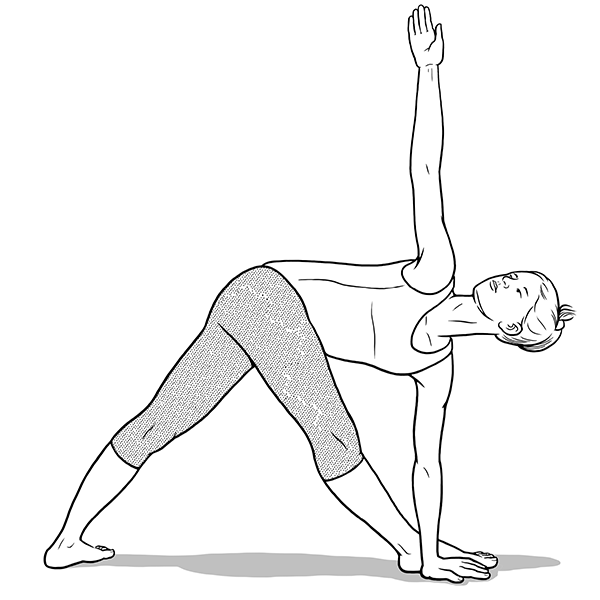

Illustration 33—Second Chakra Pose: The second chakra pose, parivrtta trikonasana, is also called twisting or revolved triangle pose. This pose activates the sacral chakra and therefore your creativity and emotions. Imagine orange flowing through your body for an increased effect. illustration by mary ann zapalac

Exercise: Second Chakra Pose: Parivrtta Trikonasana (Twisting Triangle Pose)

Barat suggests a pose called twisting triangle for the second chakra. If twisting triangle is too difficult, go with the simpler triangle pose, which omits the twisting.

- • Stand in mountain pose. On an exhale, step your feet into a wide stance, about four feet apart. Raise your arms parallel to the floor at your sides, palms down.

- • Turn your left foot in between 45 and 60 degrees to the right and your right foot 90 degrees to the right. Align your right heel with your left heel in a straight line. Turn your right thigh outward so that the center of your right knee is in line with the center of your right ankle.

- • Inhale and grow long through your spine. Exhaling, turn your torso to the right. Align the points of your hips with your mat and extend them. Bring your left hip to the right, shift the top of this thigh bone back, and dig your left heel into the mat. Lean over your right leg and reach your left hand down, resting it on the inside or outside of your right foot, your shin, on a block, or on the floor, whichever is most comfortable for you.

- • Stretch your right arm toward the ceiling. Keep your head in a neutral position, eyes front, or turn your head and gaze up toward your right hand. Align your body in a plane, not bending forward or backward, with your chest and pelvis open.

- • Breathe, increasing the stretch on each exhale as you are able. Hold the pose between thirty seconds and a minute.

- • Come out of the pose on an inhale. Return your arms to your sides and straighten your feet. Repeat on the other side.

This pose is beneficial for relieving digestive problems, lower backache, and sciatica. It is also good for relieving stress and anxiety. Avoid this pose if you have migraines, low blood pressure, headaches, diarrhea, insomnia, or spinal conditions.40

Illustration 34—Third Chakra Pose: The third chakra pose, ustrasana, is also called camel pose. This pose expands your solar plexus center to aid in everything from digestion to activation of your personal power. It also awakens your heart chakra. Visualize yellow to further energize the third chakra. illustration by mary ann zapalac

Exercise: Third Chakra Pose: Ustrasana (Camel Pose)

This asana is similar to a backbend. It assists the third chakra as well as several others. Directions are as follows:

- • Warm up your back by moving around for a while. Loosen up your shoulders and arms, raise your legs up, wiggle your hips.

- • Kneel on the floor or a mat with your knees hip-width apart and your thighs perpendicular to the floor. Make sure the soles of your feet face upward and your toenails touch the ground.

- • Place your palms on your lower back and breathe deeply.

- • Lean backward, keeping your hips pressed forward so they are over your knees. Keep your tailbone slightly tucked under.

- • Tuck your toes while leaning back, and move your hands to your heels. If you are really flexible you can slowly release your head back, being careful with your neck. You can also keep your head in a neutral position, neither flexed nor extended, or drop it back.

- • Remain in this pose between thirty seconds and a minute. To exit, bring your hands to the front of your pelvis at the hip bones. Inhale and lift your head and torso up by pushing your hip points down toward the floor. If your head is back, lead with your chest to come up. Rest for a few breaths and come completely out of the pose.

This pose is known for toning the limbs and strengthening the chest, abdomen, and thighs. It can improve the state of most of your bodily systems, from digestive to endocrine, and is helpful for asthma, bronchitis, diabetes, thyroid and parathyroid disorders, and many intestinal and genitourinary disorders. It will also reduce fat on the thighs, loosen the vertebrae, and release tension in the genital glands. Do not do this pose if you have high or low blood pressure, migraines, insomnia, or serious low back or neck injuries.41

Illustration 35—Fourth Chakra Pose: The fourth chakra pose, bhujangasana, is also called cobra pose. This pose stretches open the heart chakra and unifies body and soul. Picturing green streaming through your body while performing this pose will invite healing on every level. illustration by mary ann zapalac

Exercise: Fourth Chakra Pose: Bhujangasana (Cobra Pose)

This well-known asana is ideal for optimizing the healing powers of the heart chakra in that it emphasizes your chest, inviting a deepening of your breathing. This balance point between the lower and higher chakras allows the increased flow of love to heal everything from grievances to physical heart disorders. Perform it this way:

- • Lie on your stomach on the floor or a mat with your legs and the tops of your feet resting on the floor. Using your back muscles to lift your torso, place your hands palms down on the floor under your shoulders, your upper arms perpendicular to the floor, and hug your elbows toward the side of your body as you keep your forearms on the floor. This is actually an asana in itself, called Sphinx Pose. Exhale.

- • Press the tops of your feet, thighs, and pubic area into the floor.

- • Inhale and straighten your arms, lifting your chest off the floor. Stop while your pubic bone is still resting on the floor.

- • Press your tailbone toward your pubic area and lift the pubis toward your navel, then firm your shoulder blades toward the spine and expand your ribs. Lift the top of your body as if through the top of your sternum—but don’t push your front ribs forward. Feel the bend distributed throughout your spine.

- • Hold this pose for fifteen to thirty seconds.

- • Release the pose with an exhalation.

The cobra opens your chest, strengthens your spine, and firms your buttocks. It can be good for sciatica and asthma; as ancient texts suggest, it increases bodily heat, awakens kundalini, and eliminates disease. Avoid this pose if you have an injured back, carpal tunnel syndrome, or headaches.42

Illustration 36—Fifth Chakra Pose: The fifth chakra pose, dhanurasana, is also called bow pose. This pose will move energy through your throat, connecting all parts of your body for expressive communication. When in this pose, consider visualizing blue energy flowing like water through your body. You can also hum or tone to further open this chakra. illustration by mary ann zapalac

Exercise: Fifth Chakra Pose: Dhanurasana (Bow Pose)

A good fifth chakra asana is called bow pose.

- • Lie on your belly with your feet hip-width apart, arms resting at your sides.

- • Bend your knees and grasp your ankles with your hands.

- • On an inhale, left your chest off the floor and pull your legs up as high as is comfortable. The body will resemble the smooth curve of a bow. Keep your legs together instead of splaying out. Squeeze your inner thighs.

- • To release from the pose, slowly lower the legs until the knees are on the floor, then lower the torso.

This exercise strengthens your legs and hips, massages the spine, opens the heart, improves blood circulation, helps regulate the sexual glands, directs oxygen to the upper part of the body, and rejuvenates the entire body. Do not do this if you have kidney issues, neck injuries, cervical spondylitis, arteriosclerosis, or glaucoma.43

Illustration 37—Sixth Chakra Pose: The sixth chakra pose, adho mukha svanasana, is also called downward facing dog. You will experience increased blood and subtle energy to the third eye during this pose, cultivating your clairvoyant and observational powers. Visualize purple energy moving through your body while in this pose and disengage from limiting thoughts. illustration by mary ann zapalac

Exercise: Sixth Chakra Pose: Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward Facing Dog)

This pose, also called downward facing dog, uses the push-pull dynamics of yoga. Steps are as follows:

- • Come to the floor on your hands and knees. Your knees should be directly below your hips and your hands a tad in front of your shoulders. Spread your palms and press the balls of your feet into the floor.

- • Exhale and lift your knees away from the floor, initially keeping them slightly bent, with your heels lifted off the floor. Lengthen your tailbone away from the back of the pelvis and press it toward your pubis.

- • On the next exhale push the tops of your thighs back, stretching your heels toward the floor. Simultaneously straighten your knees but don’t lock them. Firm up your outer thighs and roll your upper thighs inward just a bit.

- • Tightening your outer arms, press the bases of your index fingers into the floor. Now lift up along your inner arms between your wrists to the top of your shoulders, firming your shoulder blades against your back before widening them to draw them toward your tailbone.

- • Keep your head between your upper arms.

- • Hold for several deep breaths and then exit the pose.

Downward dog relieves stress and energizes your body, relieving menstrual symptoms, preventing osteoporosis, improving digestion, and relieving headaches, insomnia, back pain, high blood pressure, sinusitis, and more. This pose is not advised if you are pregnant or have diarrhea, ear or eye infections, carpal tunnel syndrome, high blood pressure, or a headache.44

Illustration 38—Seventh Chakra Pose: The seventh chakra pose, savasana, is also called corpse pose. While in corpse pose, sense your connection to the ground and allow this secure feeling to free you from fears inhibiting the seventh chakra’s white light. illustration by mary ann zapalac

Exercise: Seventh Chakra Pose: Savasana (Corpse Pose)

This asana calms and balances. It is often practiced at the end of a yoga session for relaxation and integration. Directions are as follows:

- • Lie on your back on the floor.

- • Stretch your legs and spread them a natural and comfortable width apart.

- • Draw your shoulder blades under while tilting your chin toward your chest. Now relax your shoulders and chin and let go.

- • Let your arms fall by your sides in a comfortable position.

- • Visualize the pulsing of your seventh chakra.

This pose calms your brain and body, lowering blood pressure and reducing fatigue and insomnia. Do not do it if it causes discomfort, if you have a back injury, or if you are pregnant.45

Bridging past and present, we have mined Eastern chakra medicine techniques to support chakra healing and balancing. From Patanjali, a famous yogi from the past, we have borrowed and updated practices including the yamas and niyamas. We’ve added age-old processes including pranayama, mudras, and eye exercises, as well as yoga bandhas, or moves. We’ve also included asanas (yoga postures), adding a special twist. All of this we’ve done to bring time-tested chakra medicine practices into your home and world.

We now move into an additional chapter of chakra practices, one that blends West and East in a plethora of approaches.