You will find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view.

Who’s more foolish, the fool? Or the fool who follows him?

—SAYINGS OF OBI-WAN KENOBI, STAR WARS

In Chapter 1, we looked at how human beings simultaneously exist in two worlds. There’s the physical world of absolute truth and the culturescape of relative truth. In the culturescape all the ideas we hold dear—our identity, our religion, our nationality, our beliefs about the world—are nothing more than mental constructs we’ve chosen to believe. And like all mental constructs, many are merely opinions we believe because they were drilled into us as children and accepted by the culture we grew up in.

Human beings are far less rational than we think. Many ideas we hold dear and cling to as “truth” fall apart under close inspection. Our mental constructs of the world can change, pivot, expand, and shrink as human cultures, ideologies, and opinions collide, dance, and clash with each other. Just as disease is spread by contagion from host to victim, so ideas are spread in the same way. We often take on ideas not through rational choice but through “social contagion”—the act of an idea spreading from mind to mind without due questioning.

Thus our so-called “truths” are rarely optimal ways of life. As consumer psychologist Paul Marsden, PhD, wrote in a paper called “Memetics and Social Contagion: Two Sides of the Same Coin?”:

Whilst we may like to believe that we consciously and rationally decide on how to respond to situations, social contagion evidence suggests that some of the time this is simply not the case. Rather than generating and “having” beliefs, emotions, and behaviours, social contagion research suggests that, in some very real sense, those beliefs, emotions, and behaviours “have” us. . . . When we are unsure of how to react to a stimulus or a situation, these theories suggest that we actively look to others for guidance and consciously imitate them.

It’s a stunning statement. Dr. Marsden is saying that when we make decisions, we’re more likely to defer to the hive mind than to make a decision based entirely on our own thoughts and best interests. We don’t have beliefs so much as beliefs “have” us.

Dr. Marsden continues:

The evidence shows that we inherit and transmit behaviours, emotions, beliefs, and religions not through rational choice but contagion.

This is perhaps one of the most important lines in Dr. Marsden’s paper. We think we’re making a rational decision. But often, the decision has little to do with rationality and more to do with ideas our family, culture, and peers have approved.

There’s nothing wrong with taking on ideas from the society we live in. But as our world is undergoing exponential change at a staggering pace, following the masses and doing what’s always been done isn’t a path that leads to being extraordinary. Ideas, memes, and culture are meant to evolve and change, and we are best served when we question them.

We know intellectually that this sort of change happens, yet billions of us cling to self-defeating rules from the past that should not exist in today’s world because technology, society, and human consciousness have simply evolved beyond them.

In Chapter 1, you learned about the Himba tribe and their difficulty with seeing the color blue because they have no word for it. Words play an important role in cognition. So I coined a name for these outdated rules so we can see them better: The word I use is “Brules.”

A Brule is a bulls**t rule that we adopt to simplify our understanding of the world.

We use Brules to categorize things, processes, and even people. Brules are handed down by our tribe—often our family, culture, and educational system. For example, do you remember choosing your religion? Or how you got your ideas about love, money, or the way life works? Most of us don’t. Many of our most formative rules about how to live come through others. And these rules are tightly bound to ideas of what is good and bad, right and wrong.

Each of us lives by thousands of rules. When we aren’t sure what to do, we follow the example of those who came before us. Kids follow their parents, who followed their parents, who followed theirs, and so on back in time.

This means that often we are not Christian or Jewish or politically right or left because we decided we wanted to be, but simply because we happened to be born in a particular family at a particular time and, through memetics and social conditioning, adopted a particular set of beliefs. We may decide to take a certain job (as happened to me when I became a computer engineer), go to law school, get an MBA, or join the family business, not because we made a rational decision that this was the path we wanted to follow but because society programmed us that we should.

You can see from an evolutionary standpoint how it would be efficient to mimic the patterns modeled by those who came before. Ideas such as how to harvest, hunt, cook, and communicate get passed down from generation to generation, allowing civilization to steadily grow in complexity and scale. But it means we may be living our lives according to models that haven’t been upgraded for years, decades, even centuries. Blindly following may be efficient, but it’s not always smart.

When we look at them closely, we often find that Brules were imposed on us for convenience. To question and dissect these Brules is to take a step into the extraordinary.

My life of questioning the Brules started at age nine. That’s when a McDonald’s opened close to my home. Everywhere I turned, it seemed, there were ads showing mouthwatering pictures of McDonald’s cheeseburgers. Man, they looked good. And I so so so craved a Happy Meal. But I had been brought up as a Hindu and therefore had been told that I could absolutely, positively not eat beef. Ever.

McDonald’s had created a phenomenon of manufactured demand. I had never tasted beef, but thanks to all those ads and images of people “lovin’ it,” I concluded that McDonald’s burgers were going to be the greatest meal I’d ever tasted in my nine years on planet Earth. The only thing stopping me was that, culturally, I wasn’t supposed to eat beef, since it would anger the gods (or something similarly dreadful).

My parents had always encouraged me to question things, so I felt comfortable asking my mom to explain to me why I couldn’t eat beef. She replied that it was part of our family’s culture and religion. “But other people eat beef. Why can’t Hindus eat it, too?” I persisted.

Wise teacher that she was, she said, “Why don’t you go find out?” There was no Internet back then, but I pored over my Encyclopedia Britannica and developed a theory about ancient India, Hindus, cows, and beef eating that I took back to my mother. Basically, it went like this: “Mom, I think the ancient Hindus loved having cows as pets because they were gentle and had big, beautiful eyes. Cows were also very useful: They could plow the fields and provide milk. So maybe that was why Hindus back then wouldn’t eat beef when they could so easily eat goat, pig, or any other less awesome animal. But last I checked, we have a dog and not a cow, and so I think I should be allowed to eat beef burgers.”

I don’t know what was going on in my mom’s head, but she agreed, and that’s how I got to taste my first beef burger. Frankly, it was overrated. But still—boom! Just like that, a dogmatic model of reality I’d grown up blindly following was shattered.

I started questioning everything else. By nineteen, I had discarded religion—not because I wasn’t spiritual but because I felt that calling myself a Hindu was separating myself from the billions of spiritual people who weren’t Hindu. I wanted to embrace the spiritual essence of every religion, not just one. Even as a teen, I could not understand the whole idea of being bound to one singular religion for life.

I was fortunate to have parents who challenged me and allowed me to create my own beliefs. But if a nine-year-old can bust a Brule, the rest of us should be able to question them, too.

Take a moment and think about the religious or cultural norms that were transmitted to you. How many would you say are truly rational? They may be outmoded or proven untrue by today’s thinkers or researchers. Many might even cause terrible pain. I’m not advocating that you instantly reject all the rules you’ve ever followed, but you must question your rules constantly in order to live by the code that is most authentic to your goals and needs. “My family/culture/people have always done it this way” is not an acceptable argument.

As you get on the path to the extraordinary, you must remember that within the culturescape there are no sacred cows that cannot be questioned. Our politics, our education and work models, our traditions and culture, and even our religions all contain Brules that are best discarded.

Below are some common Brules we live by, often without even realizing it, and some different ways I’ve come to think about them. They’re among the biggest Brules I challenged. Escaping them shifted my life forward in dramatic ways. These are the four areas in which I decided to eliminate a Brule from my worldview:

1. The college Brule

2. The loyalty to our culture Brule

3. The religion Brule

4. The hard work Brule

As you read this, ask yourself if you might be held back by any of these Brules.

In addition to saddling many young people with massive debt for decades, studies have shown that a college education really doesn’t guarantee success. And does a college degree guarantee high performance on the job? Not necessarily. Times are changing fast. While Internet giant Google looks at good grades in specific technical skills for positions requiring them, a 2014 New York Times article detailing an interview with Laszlo Bock, Google’s senior vice president of people operations, notes that college degrees aren’t as important as they once were. Bock states that “When you look at people who don’t go to school and make their way in the world, those are exceptional human beings. And we should do everything we can to find those people.” He noted in a 2013 New York Times article that the “proportion of people without any college education at Google has increased over time”—on certain teams comprising as much as 14 percent.

Other companies are taking note. According to a 2015 article in iSchool-Guide, Ernst and Young, “the largest recruiter in the United Kingdom and one of the world’s largest financial consultancies, recently announced that they will no longer consider grades as the main criteria for recruitment.” The article quoted Maggie Stilwell, Ernst and Young’s Managing Partner for Talent: “Academic qualifications will still be taken into account and indeed remain an important consideration when assessing candidates as a whole, but will no longer act as a barrier to getting a foot in the door.”

I’ve personally interviewed and hired more than 1,000 people for my companies over the years, and I’ve simply stopped looking at college grades or even at the college an applicant graduated from. I’ve simply found them to have no correlation with an employee’s success.

College degrees as a path to a successful career may thus be nothing more than a mass societal Brule that’s fading away quickly. This is not to say that going to college is unnecessary—my life at college was one of the best memories and growth experiences I’ve ever had. But little of that had to do with my actual degree or what I was studying.

I come from a very small minority ethnicity from western India. My culture is called Sindhi. The Sindhis left India after 1947 and are living as a diaspora; that is, scattered all over the world. Like many cultures that live as a diaspora, there’s a firm desire to protect and preserve the culture and the tradition. As part of that, in my culture, it is considered absolutely taboo to marry anyone outside our ethnicity—not even another Indian. So you can imagine how shocked my family was when I told them I wanted to marry my then-girlfriend, Kristina (now my wife), who is Estonian. I remember well-meaning relatives asking me, “Do you really want to do this? . . . Your children are going to be so confused! . . . Why would you disappoint your family like this?”

At first I feared following my heart because I felt I would cause great disappointment for those I loved. But I realized that with a huge life decision such as this, I shouldn’t do something to make someone else happy that would make me so unhappy. I wanted to be with Kristina. So I married her. I rejected the Brule, so common in my generation, that we should marry only people of our ethnicity, religion, and race as it was the safest way to happiness and the “right” thing to do for the family or creed. Kristina and I have been together for sixteen years, married for thirteen. Our two kids, far from being “confused,” are learning multiple languages and happily becoming citizens of the world (my son, Hayden, had traveled to eighteen countries by the time he was eighteen months old). My children participate in Russian Orthodox, Lutheran, and Hindu traditions with their grandparents. But they aren’t limited to any one religion. They get to experience all the beauty of human religions without being locked into any one path. Which brings us to the next big Brule.

Okay, here’s a touchy question. Do we really need religion? Can spirituality exist without religious dogma? These are only a few of the questions being asked about religion today. Right alongside a rise in fundamentalism, we’re seeing a rise in questioning of the fundamentals. Do you remember the day you chose your religion? Few people do because few people get to choose their religion. Generally, it’s a series or cluster of beliefs implanted in our minds at a young age, based on our parents’ religious beliefs. And for many, the desire to belong to a family or tribe overrides our rational decision-making process and gets us to adopt beliefs that may be highly damaging.

While religion can have immense beauty, it can also have immense dogma that causes guilt, shame, and fear-based worldviews. Today the majority of people on planet Earth who are religious choose a single religion to subscribe to. But this percentage is shrinking as more and more people, especially millennials, are adopting the model “Spiritual But Not Religious.”

I believe that religion was necessary for human evolution, helping us develop guidelines for good moral conduct and cooperation within the tribe hundreds and thousands of years ago. But today, as humanity is more connected than ever and many of us have access to the various wisdom and spiritual traditions of the world, the idea of adhering to a singular religion might be obsolete. Furthermore, I believe that the blind acceptance of religious dogma is holding us back in our spiritual evolution as a species.

The core of a religion may be beautiful spiritual ideas. But wrapped around them are usually centuries of outdated Brules that few bother to question.

Can a person be a good Muslim without fasting during Ramadan? A good Christian without believing in sin? A good Hindu who eats beef? Is religion an aging model that needs to be updated?

A better alternative, in my opinion, is not to subscribe to one religion but to pick and choose beliefs from the entire pantheon of global religions and spiritual practices.

I was born in a Hindu family, but over the years, I’ve created my own set of beliefs derived from the best of every religion and spiritual book I’ve been exposed to. We don’t pick one food to eat every day. Why must we pick one religion? Why can’t we believe in Jesus’ model of love and kindness, donate 10 percent of our income to charity like a good Muslim, and also think that reincarnation is awesome?

There is much beauty in the teachings of Christ, the Sufism of Islam, the Kabbalah from Judaism, the wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita, or the Buddhist teachings of the Dalai Lama. Yet humanity has widely decided that religion should be absolutist: In short, pick one and stick to it for the rest of your life. And worse—pass it on to your children through early indoctrination, so they feel they have to stick to one true path for the rest of their lives. Then repeat for generations.

Choose a religion if it gives you meaning and satisfaction, but know that you don’t have to accept all aspects of your religion to fit in. You can believe in Jesus and not believe in hell. You can be Jewish and enjoy a ham sandwich. Don’t get trapped in preset, strict definitions of one singular path, thinking you must accept all of a particular tribe’s beliefs. Your spirituality should be discovered, not inherited.

This may start as a worthy idea and morph into a tyrannical Brule. Parents want to encourage their kids to stick with challenges, work toward goals, and not give up. But that can get twisted into a Brule: If you aren’t working hard all the time, you’re lazy and won’t be successful.

This Brule also leads to a corollary Brule that work must feel like a slog. It can’t be exciting or meaningful and certainly not fun. Yet a Gallup study shows that people who work in jobs that provide them with a sense of meaning and joy retire much later than those who work in jobs that provide no sense of meaning. When you aren’t suffering for your paycheck, you’re likely to be more engaged and committed to what you’re doing. And how long can you afford to not like what you do given that most of us spend the majority of our waking hours at work? As educator and minister Lawrence Pearsall Jacks wrote:

A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play; his labor and his leisure; his mind and his body; his education and his recreation. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing, and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself, he always appears to be doing both.

In my life I’ve always made a conscious choice to work in fields where I love what I do so much that it ceases to feel like work. When you love what you do, life seems so much more beautiful—in fact, the very idea of “work” dissolves. Instead, it feels more like a challenge, a mission, or a game you play. I encourage everyone to try to move toward work that feels this way. It does not make any sense to spend the majority of our waking hours at work, to earn a living, so we can continue living a life where we spend the majority of our waking hours at work. It’s a human hamster wheel. Therefore, always seek work that you love. Any other way of living misses the point of life itself. It won’t happen overnight, but it’s doable. As you progress through this book, I’ll share some mental models and practices to get you there faster.

How can we spot Brules that limit us and break free? The first step is to know how they got installed within you in the first place. There are five ways I believe we take on Brules. When you understand these infection mechanisms, you’ll be better able to identify which rules of the culturescape might be reasonable to use for planning your life and which ones may be Brules.

We absorb most beliefs uncritically as children during our extremely long maturity period. While other animals mature relatively quickly or can run or swim for their lives soon after birth, we human beings are helpless at birth and remain highly dependent for years afterward. During this time we are, as Sapiens author Yuval Noah Harari describes, like “molten glass”—highly moldable by the environment and the people around us:

Most mammals emerge from the womb like glazed earthenware emerging from a kiln—any attempt at remolding will only scratch or break them. Humans emerge from the womb like molten glass from a furnace. They can be spun, stretched, and shaped with a surprising degree of freedom. This is why today we can educate our children to become Christian or Buddhist, capitalist or socialist, warlike or peace loving.

Our malleable brains as children make us amazing learners, receptive to every experience and primed to take any shape our culture decrees. Think, for example, about how a child born in a multicultural home can grow up to speak two or three languages fluently. But it also causes us to take on all forms of childhood conditioning.

Ever notice how often a child asks why? The typical parent’s response to the steady barrage of why, why, why is usually something along the lines of:

“Because that’s the way it is.”

“Because God wanted it this way.”

“Because Dad says you need to do it.”

Statements like these cause children to get trapped in a thicket of Brules they may not even realize are open to question. Those children grow up to become adults trapped by restrictions and rules that they have taken to be “truth.”

Thus we absorb the rules transmitted by culture and act in the world based on these beliefs. Much of this conditioning is in place before the age of nine, and we may carry many of these beliefs until we die—until or unless we learn to challenge them.

As a parent myself, I know how difficult it can be to answer with honesty and sincerity every question a child poses. I was in the car with my son in the summer of 2014 when Nicki Minaj’s song “Anaconda” came on the radio without my noticing. As the key verse rang out about a particular “anaconda” who doesn’t “want none unless” it’s “got buns hun,” my seven-year-old son, Hayden, asked me, “Dad, why does the anaconda only want buns?”

I turned red, as most parents would. And then in an act I know you’re going to forgive me for, I did what I think any other dad in my situation would do. I lied.

“It’s a song about a snake that only loves bread,” I said.

Hayden bought it. Phew. Later that day, he told me he wanted to write a song about a snake with healthier eating habits.

I’ve fielded my share of difficult “why” questions from my kids. I certainly asked my parents a lot of them. I bet you did, too. And your parents probably did their best to answer you. But some of their answers, especially phrases such as, “because that’s the way it is,” might sometimes have set up Brules you’re still following.

The men and women of our tribe whom we see as authority figures, usually people we depend on in some way, are powerful installers of rules. Certainly that includes our parents but also relatives, caregivers, teachers, clergy, and friends. Many may be wise people with our best interests in mind who want to impart rules that will serve us well in life—such as the Golden Rule about treating others as we would want to be treated. But because we give them authority, we’re also vulnerable to those who pass down Brules that they either seek to manipulate us with or that they genuinely believe themselves, however wrongly.

Authority has proved to have an astonishing, and potentially dangerous, hold over us.

During our evolution as a sentient species, we needed leaders and authority figures to help us organize and survive. With the advent of literacy and other skills for acquiring, retaining, and sharing information, knowledge is now far more evenly distributed and widely available. It’s time we stopped behaving like submissive prehistoric tribe members and started questioning some of the things our leaders say.

Take for example, fear-based politics. It’s common in the world today for politicians to gain support by creating fear of another group. The Jews, the Muslims, the Christians, the Mexican immigrants, the refugees, the gays are all blamed in one country or another by a politician seeking votes. We need to stop buying into this type of misuse of authority.

But of course it’s not just authority figures on the largest scale who dominate us. Interestingly, some people express feeling a sense of freedom after their parents die, because they finally feel able to follow their own desires, opinions, and goals, free of parental expectations and the pressure to conform to rules their parents approved of.

We have a tendency to take on Brules because we want to fit in. We’re a tribal species, evolved to find security and kinship with each other in groups. It was safer than going it alone. Thus survival depended on being accepted within the tribe. But sometimes in order to be part of a tribe, we take on the tribe’s beliefs, irrational as those may be. So in exchange for acceptance, we pay a price in individuality and independence. It’s almost a cliché, for example, that teenagers struggle to balance individuality with succumbing to peer pressure.

Tribe here refers to any kind of group with a set of beliefs and traditions—it can be a religion, a political party, a club, team, and so on. As soon as we define ourselves by a particular view, even if it’s something that we genuinely agree with, we automatically become more likely to start taking on other beliefs of the party—even if these beliefs challenge facts and science.

We see this need for belonging at its strongest when looking at the irrational beliefs people take on when they join cults. The desire to be accepted causes them to shut down their ability to question, and they accept highly illogical, irrational beliefs.

Tim Urban, who runs the amazing blog waitbutwhy.com, calls this blind tribalism. Tim writes:

Humans also long for the comfort and safety of certainty, and nowhere is conviction more present than in the groupthink of blind tribalism. While a scientist’s data-based opinions are only as strong as the evidence she has and inherently subject to change, tribal dogmatism is an exercise in faith, and with no data to be beholden to, blind tribe members believe what they believe with certainty.

You can take on the beliefs of your tribe, but you don’t have to take on all of their beliefs, especially if their beliefs are unscientific, unhelpful, or untrue.

When we take on rules because someone says, in effect, “everyone’s doing it,” we’re adopting beliefs through social proof. Think of it as approval by proxy: We believe what someone else tells us to save ourselves the effort of assessing the truth of it ourselves. If we’re led to think that “everyone” is doing it, believing it, or buying it, then we decide maybe we should, too. A modern-day example is advertising: Everyone eats this, buys this, wears this . . . this is healthy; that is unhealthy . . . this is what you need in order to make people notice you . . . and so on. You’ve seen the ads. The modern advertising age has gotten incredibly slick at using social proof to create what I call manufactured demand. Nobody really needs that much high-fructose corn syrup packaged as Happiness in a Red Can. Nor do we need the thousands of other products that exist solely to fill a void that their own commercials create. But manufactured demand turns products that are unhealthy into must-haves through the effective use of social proof to create desire. If everyone’s doing it—it must be legit.

Suppose you go on a date with someone you’re really attracted to. After the date, the person doesn’t call you back. For many of us, our internal insecurities go into overdrive: I didn’t dress well enough . . . maybe I talked too much . . . I shouldn’t have told that joke . . . and on and on. Then, without actually finding out why the person hasn’t called, we invent a bunch of Brules about love, dating, how we should act on dates, and men and women in general. But reality may tell a different story. Maybe the person lost his phone and didn’t have your number. Maybe she had a really tough week or had to deal with a family crisis.

Yet instead of looking at these logical ideas, we start to create “meaning” around the events. The meaning-making machine in our heads is constantly creating meaning about the events that we observe in our lives—particularly when they involve people we are seeking love or attention from.

Have you ever created meaning in your head about someone’s attitude or feelings toward you because of something they do? That’s the meaning-making machine in action.

You might already be tuning in to how some of the Brules in your life have been installed. Can you think of authority figures who had a lot of influence over you? Do you have a memory of doing something you disliked just to follow the herd? Did you behave according to rules that would help you fit in?

No judgment here. Remember, this is part of how humans learn. It’s how all the information of past generations gets provided to us—including good stuff like how to make fire, fashion a wheel, tell a knock-knock joke, barbecue some meat, perform CPR, and decorate a Christmas tree. It’s not all bad; it’s just that many of us need help realizing that it’s not all good, either. Some rules aren’t useful anymore or were never true to begin with. It’s time to uninstall what isn’t working.

Our culturescape is filled with many ideas that are powerful because of the sheer number of people who believe in them. Think of ideas like nation-states, money, transportation, our education system, and more. But every now and then a rebel comes along and decides that some of these colossal constructs are nothing more than Brules. Most of these rebels talk about changing things and are labeled idealists at best, or nut jobs at worst, but once in a while, a rebel grabs reality by the horns and, slowly yet decisively, shifts things.

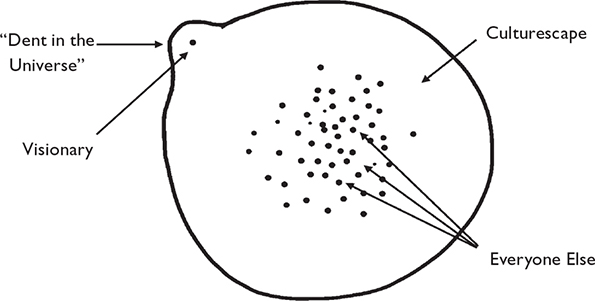

The drawing below illustrates this point. The circle is the culturescape. The mass of dots in the middle represents most folks. At first a certain person, perhaps you, decides to move away from viewing the world like everyone else. You get labeled a misfit, a rebel, a troublemaker.

But then you do something original and wild. Perhaps you write a new type of children’s book, as J. K. Rowling did with the Harry Potter books. Or, like the Beatles, you decide to move away from traditional sounds and create an original type of music. Or, like entrepreneur Elon Musk, you decide to popularize the electric car. Some misfits will fail. But some will succeed, and when they do, they make a dent in a culturescape.

And that’s when the misfit is labeled a visionary.

One such visionary is Dean Kamen. I got to visit Dean in 2015 and hear him tell me one of the most incredible stories of Brule-breaking I’ve ever heard.

Dean Kamen is a modern-day Edison. He holds more than 440 patents. He revolutionized wheelchair technology with the iBOT mobility device, spearheaded development of the leading home dialysis system, and became an icon of engineering with his invention of the Segway Human Transporter. He is a recipient of the National Medal of Technology and a member of the National Inventors Hall of Fame. With the Segway, Dean questioned the Brule of transportation: Could cities be designed without the need for cars? But personally, I’m more impressed by Dean’s questioning of the Brule of the nation-state. You see, frustrated by government, Dean started his own nation. He is, by his own fiat, Lord Dumpling, president of North Dumpling Island—a tiny island nation in Long Island Sound that he turned into his own country—only the third country in North America after the United States and Canada.

Dean Kamen was never one to follow dumb rules. As one of America’s greatest inventors, he had a strict anti-bureaucracy attitude. A healthy disregard for senseless rules and the mind of an innovator can be explosive when combined. And as he explained to me and a small group of others invited to visit him in May 2015, a giant wind turbine sparked it all.

It started out as what you could call a practical joke, but it became something much more. As a great proponent of alternative energy, Dean wanted to build a wind turbine on North Dumpling Island, his home a few miles off the coast of Connecticut, to help power his house. But New York bureaucrats (even though it’s close to Connecticut, the island is actually part of New York’s jurisdiction) said the proposed turbine was too big, and the noise would disturb the neighbors. “It’s an island,” said Dean. “There are no neighbors!” The bureaucrats wouldn’t budge. It was a stalemate.

Dean Kamen is not a man who backs down. As he told us, he was seriously bothered that New York State, which was miles away from North Dumpling, had the power to tell him how to run his island. So Dean decided that he would take no more. Speaking to a friend of his at Harvard who was an expert on constitutional law, Dean found a loophole that allowed him to secede—not just from New York but from the entire United States. And so on April 22, 1988, the New York Times carried an article: “From Long Island Sound, A New Nation Asserts Itself.”

Dean didn’t just create his own island nation. He created North Dumpling’s own constitution, anthem, and currency called (what else?) the dumpling.

How’s that for bending the Brules? Few of us grow up thinking about starting our own nation. Or currency. Dean, however, is not an ordinary person. Perhaps it was that same inquisitive mind that led him to question the Brules of transportation and invent the Segway. He had now questioned the idea of nationhood itself. But Dean wasn’t done yet.

New York didn’t relent. Its bureaucrats continued sending warning letters to Dean about the wind turbine. Dean simply sent those letters to the New York press with a statement: “See how disrespectful New York bureaucrats can be—they dare threaten the head of an independent nation-state.” The warning letters stopped.

A few months later while visiting the White House (Dean has friends in high places), Dean jokingly got President George H. W. Bush to sign a nonaggression pact with North Dumpling.

As you can imagine, all of this caused tremendous publicity. A local morning talk show decided to visit North Dumpling to do a broadcast from the island. During the filming, Dean explained, he asked one of the talk show hosts if he’d like to convert his US dollars to dumplings. The host scoffed, asking if dumplings were real currency. Dean replied that US dollars are the currency that should really be questioned. After all, the dollar had been taken off the gold standard decades ago and was now backed by thin air. The dumpling, on the other hand, was backed by Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. (Seriously. Dean knows the founders.) And, as Dean pointed out, since ice cream is frozen to 32ºF (0ºC), it had “rock-solid backing.”

As I explored Dean’s home, I found on one wall what struck me as the most important document of all. It was a framed “Foreign Aid National Treasure Bond” to President Bush in which North Dumpling Island actually gave foreign aid to the United States—in the sum of $100.

I asked Dean for the story behind the picture. He told me that North Dumpling had become the first nation in the world to provide foreign aid to the United States. And here’s why, according to the certificate:

Once the technological leaders of the world, America’s Citizens have been slipping into Woeful Ignorance of and Dismaying Indifference to the wonders of science and technology. This threatens the United States with Dire Descent into scientific and technological illiteracy. . . . The Nation of North Dumpling Island hereby commits itself to helping rescue its neighbor Nation from such fate by supporting the efforts of the Foundation for Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology in promoting excellence in and appreciation of these disciplines among the peoples of the United States of America. . . .”

Dean wasn’t giving $100 to a superpower as a joke. He was about to pull off yet another Brule-busting move using his newly formed role as an independent nation to do it. He was seeking to change the global education system to bring more attention to science and engineering.

Dean’s donation to the United States was for establishing FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), an organization with a mission: “To transform our culture by creating a world where science and technology are celebrated and where young people dream of becoming science and technology leaders.” FIRST does this through huge competitions where kids build robots of all kinds that compete in Olympic-like settings.

When I attended the FIRST robotics challenge in St. Louis, Missouri, in 2015, some 37,000 teams from high schools around the world had competed to get their robots to the finals. It was fantastic to see what those kids could build.

Dean said that he thinks one of the problems in the world today is that kids grow up idolizing sports superstars, and while there’s nothing wrong with idolizing athletic power, we also need to idolize brainpower—the engineers, the scientists, the people who are moving humanity forward through innovation. That’s what he did with FIRST. And North Dumpling Island certainly helped fuel publicity for the organization.

Whether North Dumpling Island is really a nation is beside the point. What’s important is that Dean is a guy who plays at a different level from most people. He is constantly bending and breaking the rules in pursuit of a better way to live, hacking beliefs and cultural norms that most of us accept without questioning:

With his invention of the Segway, he redefined accepted models of transportation.

With his invention of the Segway, he redefined accepted models of transportation.

With North Dumpling Island, he playfully redefined the idea of the nation-state.

With North Dumpling Island, he playfully redefined the idea of the nation-state.

With FIRST, he redefined the idea of science education being as cool to teens as sports.

With FIRST, he redefined the idea of science education being as cool to teens as sports.

Extraordinary people think differently, and they don’t let their society’s Brules stop them from advocating for a better world for themselves. Neither should you. All of us have both the ability and responsibility to toss out the Brules that are preventing us from pursuing our dreams. It all starts with one thing: questioning your inherited beliefs.

You can use the same amazing brain that took those Brules onboard to uninstall them and replace them with beliefs that truly empower you. This idea alone can be hugely liberating. Which leads us to Law 2.

Extraordinary minds question the Brules when they feel those Brules are out of alignment with their dreams and desires. They recognize that much of the way the world works is due to people blindly following Brules that have long passed their expiration date.

We have to push our systems—internally and externally, personally and institutionally—to catch up. We do that by making the first move to uninstall Brules in our own minds and then exerting upward pressure on our social systems to evolve. It can feel a little like free fall when you first start—and it is, because you’re taking your life off of autopilot. Sometimes things feel chaotic while you take over the controls but have faith in yourself. You were born to do this. The great gift of being human is our capacity to see the world anew, invent new solutions—and then use what we know to transform our lives and change our world. Culture isn’t static. It lives and breathes, made by us in real time in the flow of life, meant to change as our world changes. So, let’s do it! It starts at home, with you. Your life, on your terms.

So, what might your Brules look like? I’m not talking here about getting rid of moral and ethical standards that uphold the Golden Rule. But certain rules that lock us into long-held habits and irrational self-judgment could be worth a look (for example: I should work to the point of exhaustion every week or I’m not working hard enough . . . I should call my parents every day or I’m not being a good daughter/son . . . I should observe my religion the way my family does or I’m not a spiritual person . . . I should behave a certain way toward my mate or I’m not a good spouse . . . ) to see if a Brule is coming to call. Apply the five-question Brule Test for a reality check, and decide whether it’s a rule you want to live by or a Brule you want to bust.

Is the rule based on the idea that human beings are primarily good or primarily bad? If a rule is based on negative assumptions about humanity, I tend to question it.

For example, in the world today there’s a huge amount of guilt and shame about sex, and many rules around it. India recently tried to ban access to all pornography websites—but there was so much public outcry, the ban was ended four days later. That’s an example of a Brule based on the idea that humanity is primarily bad: Give people freedom to access porn online, and they’ll go berserk and become sexual deviants.

The Christian idea of original sin is another example of fundamental mistrust of humanity. It has caused so much guilt and shame for so many people who feel undeserving of success and good things in life. Original sin is an example of a relative truth. It’s held by one particular segment of the world population; i.e., it is not universally held across cultures. There’s no scientific evidence that we are born sinners, so it isn’t absolute truth. Yet it negatively affects millions.

Always have faith and trust in humanity. I like to remember Gandhi’s words: “You must not lose faith in humanity. Humanity is an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty.”

The Golden Rule is to do unto others as you would want them to do unto you. Rules that elevate some while devaluing others are suspect as Brules—such as rules that grant or restrict opportunities based on skin color, sexual orientation, religion, nationality, whether a person has a penis or a vagina, or any other arbitrary or subjective criteria.

Is this a rule or a belief that the majority of human beings weren’t born into believing? Is it a belief in a particular way of life or a rule about a very particular habit, such as a way of eating or dressing? If so, it’s probably a cultural or religious rule. If it bothers you, I believe you don’t have to follow it, just as I decided I would enjoy a steak or beef burger when I wanted to. Luckily for me, my family allowed me to question these rules, even though sometimes it might have made them uncomfortable.

You do not have to dress, eat, marry, or worship in a manner that you disagree with just because it’s part of the culture you’re born into. Culture is meant to be ever-evolving, ever-flowing—in a way, just like water. Water is most beautiful and useful when it’s moving—it creates rivers, waterfalls, the waves of the ocean. But when water becomes stagnant, it becomes poisonous. Culture is like water. If it’s stagnant, as in the case of dogma or the rules of fundamentalist religion, it can be poisonous. Appreciate your culture, but let it flow and evolve. Don’t buy into the dogma that your culture’s way of prayer, dress, food, or sexual conduct must stay the same as it was generations ago.

Are you following a rule because it was installed in you during childhood? Is it benefiting your life, or have you just never thought about doing things differently? We follow a large number of dangerously unhealthy rules merely because of memetics and social conditioning. Are they holding you back? If so, try to understand them, dissect them, and question them. Do they serve a purpose, or do you take them on merely by imitation? Ask yourself if these rules truly serve you and if you want to pass them down to your children. Or are these ideas—for example, ones about how to dress or traditional ideas of what is moral—stifling and restrictive. If so, let’s allow them to die a peaceful death and cut the cord so they do not end up infecting our children.

Sometimes we follow beliefs that don’t serve our happiness, but that feel as if they reflect an accepted and inescapable way of life. It could be following a career path because our family or society tells us it’s correct (as happened to me with computer engineering), or marrying a particular person, or living in a certain place or a certain way.

Place your happiness first. Only when you’re happy can you truly give your best to others—in society, in relationships, in your family and community.

It’s worth remembering these wise words from Steve Jobs when he was asked to address the graduating class at Stanford:

Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.

What are some beliefs in your life you want to question? Pick a few and try applying the Brule Test. Then try a few more. Don’t rush, and don’t expect to wake up tomorrow free of all of your Brules just because you’ve figured out what they are. Brules are powerful, and it can be hard to look squarely at the ones that have had the most influence over you. Throughout this book I’ll be sharing strategies for throwing out your Brules and replacing them with new blueprints that will inspire greater happiness, connection, and success. But before you leap forward into a new life, you have to untangle yourself from the old one. I like to recall the words of L. P. Hartley from the 1953 novel The Go-Between: “The past is a foreign country: They do things differently there.” If so, this is your chance to cross the border, visit some place new and exciting, and discover a whole new way of life.

As you pursue this quest to question, know this: Certain people will tell you that you’re wrong, that you’re being unfaithful to your family, or to your tradition, or to your cultural norms. Or that you’re being selfish. Here’s what I want you to know. Some say the heart is the most selfish organ in the body because it keeps all the good blood for itself. It takes in all the good blood, the most oxygenated blood, and then distributes the rest to every other organ. So, in a sense maybe the heart is selfish.

But if the heart didn’t keep the good blood for itself, the heart would die. And if the heart died, it would take every other organ with it. The liver. The kidneys. The brain. The heart, in a way, has to be selfish for its own preservation. So, don’t let people tell you that you’re selfish and wrong to follow your own heart. I urge you, I give you permission, to break the rules, to think outside the norms of traditional society. The Brules of the father should not be passed on to the son.

When you start hacking your life in this way, you gain a new sense of power and control. With it comes accountability and responsibility for your actions. Since you’re deciding what rules you’ll follow, your life is up to you. You can’t hide behind excuses about who or what is holding you back. It’s also up to you to hack responsibly, applying the Brules Test to make sure you aren’t violating the Golden Rule as you go.

It takes a certain amount of courage to live in this way. When you hit a certain pain point with a Brule and realize that you cannot continue to live with it, part of abandoning it could feel like abandonment of an important social structure in your life. Life beyond the Brules can be scary and surprising and exhilarating—often all at once. People might push back or hassle you, but you must be prepared to stand firm in your pursuit of your own happiness.

I like to remember the advice from my friend Psalm Isadora, an actress and well-known tantra teacher: “The people making you feel guilty for going your own way and choosing your own life are simply saying, ‘Look at me. I’m better than you because my chains are bigger.’ It takes courage to break those chains and define your own life.”

So dare to live your precious days on Earth to their fullest, true to yourself, with open heart and thoughtful mind, and with the courage to change what doesn’t work and accept the consequences. You may find that you can fly farther than you ever imagined.

“What if . . . all the rules and ways we lay down in our heads, don’t even exist at all? What if we only believe that they’re there, because we want to think that they’re there? All the formalities of morality and the decisions that we see ourselves making in order to be better (or the best) . . . what if we think we’ve got it all under control—but we don’t? What if the path for you is one that you would never dare take because you never saw yourself going that way? And then what if you realized that one day, would you take the path for you? Or would you choose to believe in your rules and your reasons? Your moralities and your hopes? What if your own hope, and your own morality, are going the other way?”

—C. JOYBELL C.