Chapter 7

Breaking up a pawn chain

Any pawn chain has a base: the rearmost pawn in the chain, which supports all the other pawns. By eliminating the base, one can undermine the entire chain. But if you cannot get to the base and destroy it (which is often the case, as the base is located at the heart of the enemy position), the chain can be attacked in other ways. By attacking it, one can often break it into several separate pieces, and so weaken the enemy position. Breaking up pawn chains is one of the most common ideas in chess.

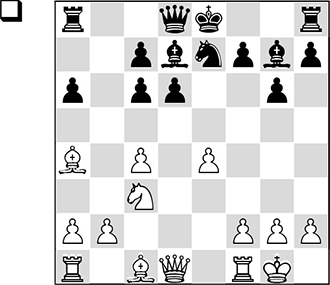

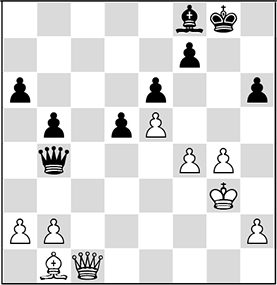

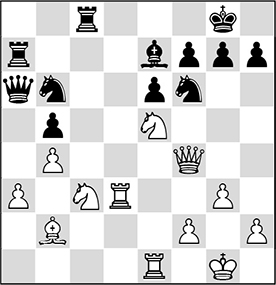

32 *

Isaak Boleslavsky

Salomon Flohr

Budapest ct 1950

The black pawn group c7-c6-d6 controls a lot of squares, and would be excellent if the black pieces were more active. For example, the knight on e7 would not be bad, if Black could play …c6-c5 and …♘e7-c6. But White does not allow his opponent to stabilise the centre:

11.c5! ♘c8

On 11…dxc5, there would follow 12.♗e3, regaining the pawn with every convenience.

Black remains a pawn down with poor development, after 11…d5 12.exd5 cxd5 13.♘xd5 ♘xd5 14.♕xd5 ♗xa4 15.♕e4+.

12.♗e3

Having driven the black knight to a prospectless position, White simply completes his development, strengthening his position in the centre.

12…0-0 13.♕d2 ♕e7 14.♖ad1 ♗e8?

Taking on c5 is no threat, so moving another piece into a completely passive position puts Black on the edge of defeat.

It was essential to be patient and continue development, whilst maintaining the tension, with 14…♖b8 or 14…♖e8.

15.f4! f5

Black is completely unready for the opening of lines, as his pieces are passive, and he has not finished developing.

More tenacious was 15…dxc5, although here too, the undefended dark squares tell: 16.e5!? (there is also the simpler line 16.♕f2 ♗d4 17.♗xd4 cxd4 18.♖xd4, effectively keeping an extra pawn) 16…f6 17.♕d8 ♕xd8 18.♖xd8 ♗f7 19.♖xf8+ ♗xf8 20.♘e4, with a strong initiative.

16.exf5 gxf5

No better is 16…♖xf5 – for example, there could follow 17.♗c2 ♖f8 18.♖fe1.

17.♖fe1 dxc5 18.♕f2 ♘d6 19.♗xc5 ♕d8 20.♗d4

Exchanging off the main defender of Black’s dark squares is the most technical approach, although, of course, White has many ways to realise his advantage.

20…♗xd4 21.♕xd4 ♕f6 22.♗b3+ ♔h8 23.♕xf6+ ♖xf6 24.♖e7 ♖c8 25.♖de1 ♗g6 26.♖1e6

The number of weaknesses in the black position allows White to convert his advantage simply by exchanging.

26…♖xe6 27.♗xe6 ♖e8 28.♖xe8+ ♗xe8 29.♘a4 ♔g7 30.♘c5 a5 31.♔f2 ♗f7 32.♗xf7 ♔xf7 33.b3!

Now, the a5-pawn is doomed, and the knight on d6 further restricted.

33…h5 34.g3 ♔e7 35.♔e3 ♘b5 36.♘b7!

The time has come to cash in.

36…c5 37.♘xa5 ♔d6 38.♘c4+ ♔d5 39.♔d3 ♘d6 40.♘xd6 cxd6 41.a3

Black resigned.

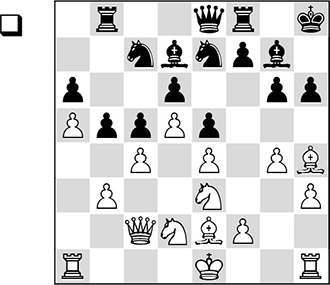

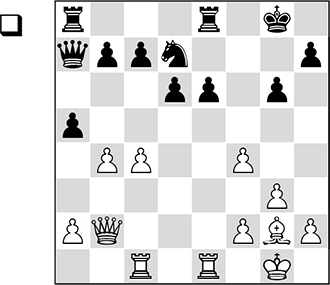

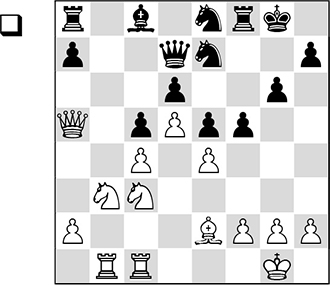

33 *

Tigran Petrosian

Anatoly Lutikov

Tbilisi ch-URS 1959 (7)

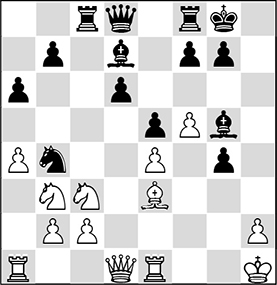

Black has just played 23…♕d8-e8.

24.b4!

A timely breaking-up of the enemy pawn chain, and a very strong and subtle decision by Petrosian. White notices the subtleties of the position and strikes a blow at the black queenside, where he would usually have direct play in the King’s Indian.

24…♘c8

24…cxb4 25.c5! ♖c8 (25…dxc5 26.d6) 26.c6! ♘xc6 27.dxc6 ♗xc6 28.♕b3 ; 24…bxc4 25.bxc5!

; 24…bxc4 25.bxc5! .

.

25.bxc5 dxc5 26.cxb5 ♘xb5

He loses immediately after 26…♗xb5? 27.♕xc5 ♕d7 28.♘ec4 f5 29.gxf5 gxf5 30.♘xe5+–.

27.♗xb5?!

More precise is 27.♕xc5! ♘d4, which gives Black certain counterplay, but after 28.♗xa6 ♖b2 29.♘ec4! ♖c2 30.0-0, White has a decisive advantage: 30…f5 31.♗xc8 ♗xc8 32.a6 fxg4 33.a7 ♘e2+ 34.♔h2 ♖c3 35.♖a3, and Black does not manage to get at the white king.

27…♖xb5

The other continuation is 27…♗xb5?! 28.♕xc5 f6 29.♘ec4 ♖f7 30.0-0 g5 31.♗g3 ♗f8 32.♕e3 ♖c7 33.♖fc1 ♗c5 34.♕f3 ♕e7, which gives Black little compensation for the pawn.

28.0-0 f5 29.f3

29…♖f7?

A useless move. Black had to begin with 29…h5! 30.♘b3 ♗h6 31.♕c3 ♘d6, and here things are not so clear.

30.♘dc4 ♖b4

Now, 30…h5? is too late: 31.exf5 gxf5 32.gxf5 ♖b4 33.♗e1 .

.

31.♗e1! ♖b7 32.♗c3 h5 33.gxf5 gxf5 34.exf5 e4 35.♔h2+–

White also wins with 35.fxe4 ♗xc3 36.♕xc3+ ♖g7+ 37.♔h2 ♕xe4 38.f6 ♖f7 39.♘e5+–.

35…exf3 36.♖xf3 ♗d4 37.♕d3 ♗f6 38.♖g1 ♔h7 39.♗xf6 ♖xf6 40.♕c3 ♕f8 41.♖g6 ♖f7 42.♖g5

1-0

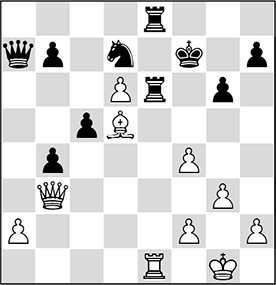

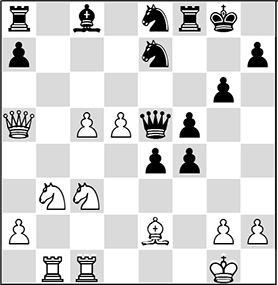

34 **

Artur Jussupow

2630

Alexander Beliavsky

2690

Frankfurt rapid 1998 (1)

It would appear that the position is roughly equal: the pawns are equal, and the opposite-coloured bishops enhance the drawing tendencies. But these considerations would only be true if queens were not on the board. All the while they are, the possibility exists of a powerful attack on the white king.

28…g5!

Black finds a way to break up White’s pawn chain and get at the white king.

29.♗b1?!

White will not manage to get his attack on the enemy king going.

It was essential to switch to defence with 29.♔f3 gxf4 30.exf4, although here too, Black has a serious initiative after 30…♕d4 31.♕d2 ♗c5.

29…gxf4+ 30.exf4

30…♕d4!

Now, the black bishop will join in and White’s position is hardly defensible.

31.♕c2 ♗c5 32.♕h7+ ♔f8 33.♕xh6+ ♔e8! 34.♕h8+ ♔d7 35.♕a8 ♕f2+ 36.♔h3 ♕f3+ 37.♔h4 ♗e7+ 38.g5 ♕xf4+ 39.♔h3 ♕f1+ 40.♔g3 ♕xb1 41.♕b7+ ♔e8 42.♕c8+ ♗d8 43.h4 ♕d3+ 44.♔g4 ♕c4+ 45.♕xc4 dxc4 46.h5 ♔f8

White resigned.

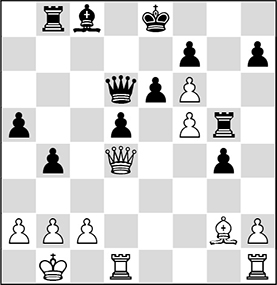

35 **

Alexander Khalifman

2655

Friso Nijboer

2605

Groningen 1997 (2)

If White plays 26.a3, Black gets control of the a-file, whilst after 26.b5, Black gets the c5-square. Exploiting the more active position of his pieces, White found a way to break up the black pawn chain:

26.c5! axb4 27.cxd6 c5

Even worse is 27…cxd6 28.♖c7 ♖ad8 29.♖xe6 ♖xe6 30.♗d5 ♔f7 31.♕e2+–.

28.♖xe6 ♖xe6 29.♗d5 ♖ae8 30.♕b3 ♔f7 31.♖e1

31…♕a3

After 31…♘f8 32.d7 ♘xd7 33.♖xe6 ♖xe6 34.♗xe6+ ♔e7 35.♗g8, Black loses his kingside pawns.

32.♖xe6 ♕xb3 33.♖e7+ ♔f8 34.♖f7+ ♔g8 35.♗xb3 b5 36.♖xd7+ c4 37.♖e7 ♔f8 38.♖xe8+ ♔xe8 39.♗c2 ♔d7 40.f3 ♔xd6 41.♔f2

Black resigned.

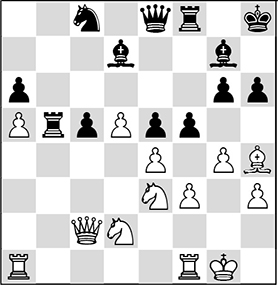

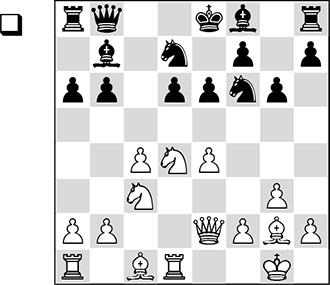

36 **

Tigran Petrosian

Lev Psakhis

Las Palmas izt 1982 (5)

The Hedgehog is a solid structure, but in this case, Black has played it poorly, and is also behind in development. The white pieces are eyeing up the queenside, and it is there that he begins successful active operations:

12.a4!

White prepares to knock out one of the Hedgehog’s ‘spikes’ and then bring his knight to the a5-square, a plan that is typical in such positions, especially if the black knight has committed itself to d7 early.

12…♗g7 13.a5 0-0

On 13…bxa5, there of course follows 14.♘b3!.

14.axb6 ♘xb6 15.♘b3! ♖a7 16.♗f4

To defend d6, Black has to allow another weakening of his pawn structure.

16…e5

No better is 16…♘c8 17.c5!.

17.♗e3 ♗c8 18.♘a5 ♖a8

Bad is 18…♖d7 19.b4!, with the threat of b4-b5.

19.♕d3

It was possible to realise the advantage in more decisive fashion: 19.c5! dxc5 20.♗xc5 ♖e8 21.♗d6 ♕a7 22.♘c6 ♕b7 23.♘xe5, not only winning material, but also continuing to dominate in the centre.

19…♗e6 20.b3 ♘c8 21.h3

This prophylaxis is aimed at dealing with the instability of the ♗e3, and stopping it being attacked by …♘f6-g4.

21…h5

With all the prophylactic moves made, and the pieces on ideal squares, it is time!

22.b4! ♕c7 23.♘d5

It was also possible to secure a decisive advantage, thanks to the passed c-pawn, by means of the energetic 23.c5! dxc5 24.bxc5 ♘e7 25.♕d6 ♖fc8 26.♕xc7 ♖xc7 27.♘d5+–.

23…♘xd5 24.cxd5 ♗d7 25.♖dc1 ♕b8 26.♘c6 ♕b7 27.♗f1 f5 28.♕xa6!

White forces transition into a winning endgame, demonstrating the same calm, technical manner of realisation.

28…♖xa6 29.♗xa6 ♗xc6 30.♗xb7 ♗xb7 31.♖c7 ♖f7 32.♖ac1 ♗a6 33.b5 ♗xb5 34.♖xc8+ ♔h7

And Black resigned.

37 **

Lajos Portisch

2635

Ulf Andersson

2565

Milan 1975 (6)

Black has no weaknesses, and his compact pieces defend each other, in addition to their king.

21…b5!

A good attempt to fight for the initiative, without at the same time taking on any special risk.

It was also possible to offer the exchange of queens with 21…♕b8 – even if White avoids this, Black can comfortably play …b6-b5.

22.cxb5

This move represents a positional concession, as the structure changes in Black’s favour. Admittedly, White does manage to keep active pieces.

The way to equalise was not simple, and contained within itself the risk of a miscalculation: 22.♘e4! bxc4 23.♖c1!. Taking on c4 with the pawn, creating a new pawn island, is obviously undesirable, and Black could easily end up with the more pleasant position. 23…♖c7 24.♘e5!, with the idea of taking on c4 with a piece, equalises.

22…axb5 23.b4

White does not want Black to play …b5-b4. In this case, White would have to play ♘c3-a4, and Black would get an outpost on d5 for his knight.

23…♕a6 24.a3 ♘b6 25.♘e5 ♖c8 26.♖d3

It was possible to maintain the tension with 26.♘e4!, and after 26…♘bd5 27.♕f3 h6!, we reach a position of dynamic equality.

26…♗f8!

In this way, Black defends the f7-pawn.

27.g4 ♘bd5

It looks stronger to exchange the active knight by 27…♘c4! 28.♘xc4 ♖xc4 29.♘e4 ♘d5, with the advantage.

28.♘xd5 ♘xd5 29.♕d4?

A blunder. He had to play 29.♕e4, retaining sufficient counterplay for equality, thanks to his active pieces.

29…f6 30.♖h3

30.♘f3 ♖c4–+.

30…fxe5 31.♕xe5 ♖f7 32.♕h5 h6 33.♖g3 ♖c2 34.♗d4 ♘f4 35.♕e5 ♕d6 36.♕e4 ♖c4

White resigned.

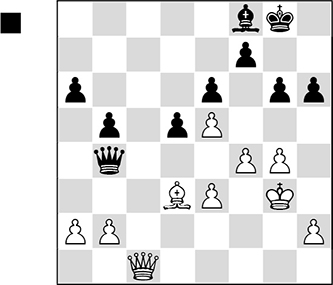

38 **

Evgeny Bareev

2665

Peter Svidler

2640

Elista ch-RUS 1997 (6)

The magnificently-posted knight on c4 prevents Black playing …b7-b6 or …b7-b5, so White’s advantage is indisputable.

25.b4!

A technical decision. The position of the ♗d4 is undermined, and the pawn on b7 becomes backward.

Of course, 25.f5 was also possible, but White did not wish to weaken his kingside dark squares further (already weakened by h2-h3).

25…f5

Black’s only means of getting activity.

26.bxc5

He wins by 26.e5! dxe5 27.bxc5 ♕xd5 28.♘xe5 – thanks to the deadly pin, Black loses a bishop. But White did not want to switch from positional play to tactical play, which is a pragmatic decision. If Black managed to find a way to save the bishop, White’s advantage would have disappeared.

26…dxc5 27.♘b6

27.d6 fxe4 28.♖xe4 also retains a large advantage.

27…♕b5

27…fxe4 28.♕xd4 ♕xh3+ 29.gxh3 cxd4 30.d6!+– – the passed pawn marches to d7, whilst the black pawns, unsupported by pieces, are going nowhere.

28.♕xb5 axb5 29.e5 ♔f7 30.g3

Also good is 30.♖b1 b4 31.♖fd1 , with the idea of taking on b4 or d4.

, with the idea of taking on b4 or d4.

30…♖a8?

Losing at once.

More tenacious was 30…b4, but after, for example, 31.♖f3 , White can put his rook on d3 and bring his king to f3, when, in time, the central passed pawns should decide the game in White’s favour.

, White can put his rook on d3 and bring his king to f3, when, in time, the central passed pawns should decide the game in White’s favour.

31.e6+ ♔e7 32.d6+ ♔xd6 33.e7 ♖fe8 34.♘xa8 ♖xe7 35.♖xe7 ♔xe7 36.♖b1! b4 37.♔g2 ♔d6 38.♔f3 ♔c6 39.♔e2

1-0

39 ***

Konstantin Sakaev

2672

Alexey Fedorov

2602

Warsaw Ech 2005 (7)

As a rule, White’s plan in such positions is to maintain firm control of e4, and play on the b-file. But in this case, White exploits the lack of coordination between the black pieces, and lands the blow.

17.f4!!

An academic positional decision, which would keep the advantage, was 17.♘d2 – this meets the aims indicated above, and keeps in reserve the typical manoeuvre ♗e2-d1-a4.

17…exf4 18.e5!

Because of the lack of piece support, the black pawns are not going anywhere, whilst White’s passed pawns spring into motion.

18…dxe5 19.♘xc5 ♕d6 20.♘b3

This retreat square was chosen so the knight does not get hit with tempo.

20.♘d3 e4 (bad is 20…f3 21.gxf3 ♕f6

Prophylaxis

22.♔h1! – and Black cannot get any benefits out of ‘his’ flank) 21.c5 ♕f6 22.♘xf4 ♕e5 gives Black practical hopes of muddying the waters, although his position is bad here too.

20…e4 21.c5 ♕e5

22.♕a4!

Taking the fourth rank under control, and also the c6-square – a threat arises of d5-d6.

22…♘f6 23.♕d4!

With the exchange of queens, White kills his opponent’s last hopes of opening lines and creating threats against the white king.

23…♘d7 24.c6

A simpler win was 24.♗b5, taking control of the c6-square, and creating the threat d5-d6.

24…♕xd4+ 25.♘xd4 ♘e5 26.c7 ♗d7 27.♗b5!

One of the blockaders of the passed pawn can simply be exchanged, and this possibility should be seized.

27…♗xb5 28.♖xb5 a6 29.♖b6 ♘c8 30.♖e6 ♘d3 31.♖b1 ♖a7 32.d6 ♘xd6 33.♖xd6 ♖xc7 34.♘d5

The white knights occupy dominating positions, quickly organising a mating attack.

34…♖c4 35.♘e6 ♖a8 36.♖d7

1-0

40 ***

Garry Kasparov

2785

Zbynek Hracek

2625

Yerevan ol 1996 (7)

The white king is securely placed, whilst Black’s is in the centre. White needs to get at the latter, so…

17.g4!

The strongest and most energetic, not losing a single tempo!

It was also possible to play in a more positional style, avoiding sacrifices, with 17.h3 ♕b6 18.♕d3, followed by g2-g4.

17…fxg4 18.f5! ♖g8

18…exf5 19.e6 ♖g8 20.exf7+ ♔xf7 21.♗g2, with a strong attack.

18…♕c7 19.fxe6 ♗xe6 (19…fxe6 20.♘f6+ ♔d8 21.♘xd5 exd5 22.♕xd5+ ♔e8 23.♗c4 ♖f8 24.♖hf1+–) 20.♘g7+ ♔d7 21.♘xe6 fxe6 22.♕xg4 ♕c6 23.♗h3, with the initiative.

19.♘f6+! ♗xf6 20.exf6 ♕d6 21.♗g2

Now, the threat of a sacrifice on d5 hangs over Black.

21…♖g5

On 21…♗b7, the strongest is 22.♖hf1!, with the threat to take on e6.

The only hope was 21…♖b5! 22.♖he1 ♔d8! – here, Black can again put up some sort of defence.

22.♗xd5!

The attack on the central files decides.

22…♗d7 23.♖he1! h6

23…♖xf5 24.♗xe6 ♕xd4 25.♗xf5++–.

24.fxe6 fxe6 25.♕a7

Black resigned.

41 ***

Joel Benjamin

2580

Vadim Zviagintsev

2635

Groningen 1997 (1)

In such positions, Black’s main task is to play …d6-d5 in a favourable form, sometimes at the cost of a sacrifice. White’s task is to prevent this, and retain the maximum control over the key squares. Now, if he allows g4-g5, the knight will have to retreat to a passive position, from where it will not take part in the fight for the central squares. Black’s decision is typical, striking and very strong, all at the same time:

14…h5!

14…h6 was also possible, but does not solve the overall problem – after all, White can just in time play h2-h4, and then g4-g5.

15.g5

On 15.h3, there follows 15…hxg4 16.hxg4 ♘h7!, with the idea of …♗e7-g5, ensuring a splendid blockade on the dark squares.

15…♘g4 16.♗xg4 ♗xg5!

Even if there had not been this zwischenzug, Black would have obtained good play by just taking on g4. But the text, of course, is even stronger.

17.♖e1 hxg4 18.♔h1

18…g6

White has no light-squared bishop, so here the break 18…d5! was especially strong: 19.♗c5 ♗e7 20.♘xd5 ♘xd5 21.♕xd5 ♗xc5 22.♘xc5 ♗xf5 (also good is 22…♗c6 ) 23.♕xd8 ♖fxd8 24.♘xb7 ♖d7 25.exf5 ♖xb7 leaves Black good winning chances.

) 23.♕xd8 ♖fxd8 24.♘xb7 ♖d7 25.exf5 ♖xb7 leaves Black good winning chances.

19.♕xg4!

White seizes his fleeting chance and forces perpetual check.

19.♗xg5 ♕xg5 20.♖g1 gxf5 21.♕xd6 ♘xc2 22.♕xd7 ♘xa1 23.♘xa1 ♖fd8 24.♕xf5 ♕xf5 25.exf5 ♖c4 26.♘c2 ♖d3 leads to Black’s advantage.

19…♗xe3 20.♖xe3 ♘xc2 21.♖g3 ♖xc3

Nothing was changed by 21…♘xa1 22.♕h5 ♗e8 23.fxg6 fxg6 24.♖xg6+.

22.bxc3 ♘xa1 23.♕h5 ♗e8 24.fxg6 fxg6 25.♖xg6+ ♗xg6 26.♕xg6+

Draw.

42 ***

Magnus Carlsen

2772

Dmitry Jakovenko

2742

Nanjing 2009 (10)

White has more space and a small lead in development. His plan is clear: to advance his f-pawn, for which purpose his knight will come to g5 or h4, depending on the situation. What should Black do in his turn? It is logical either to blockade the white pawn chain or to break it up. All problems are solved by the surprising break:

15…f6!

White cannot exploit the Q v R opposition on the e-file, nor support his e5-pawn with the f-pawn. On his next move, Black wants to play …♘e7-g6, putting further pressure on the e5-pawn. Now, White is not able to move the ♘f3 anywhere, and sooner or later he will have to exchange on f6. In this case, he will lose his entire space advantage, the manoeuvrability of his knight and his advantage – the game will be roughly equal.

Instead, in the game, there followed 15…♖fe8, which allowed White to carry out his plan: 16.♘h4 ♘g6 17.♘xg6 ♕xg6 18.♕d2 ♘f8 19.f4 ♕f5 20.♘d1 f6 21.♘e3 ♕d7 22.♕d3 fxe5 23.dxe5 ♘e6 24.f5 ♘c5 25.♕d4 ♘e4 26.♘xd5 ♕xd5 (more tenacious was 26…♘c5, after which there could have followed 27.f6 ♖ed8 28.f7+ ♔f8 29.e6 ♘xe6 30.♕e4 ♕xd5 31.♕xh7, with a decisive attack) 27.♕xe4, and White realised his extra pawn.

The break 15…c5 is not bad, but does not fully resolve all the problems, after, for example, 16.♘b5 (the endgame possible after 16.♘g5 ♕g6 17.♕xg6 fxg6 looks fully defensible, whilst after 18.♘b5, with the idea of penetrating Black’s camp with the knights, there follows 18…♖fc8!, bringing the rook to c6) 16…♕g6 17.♕d2, and White has the better game.

If Black tries to organise a blockade with 15…f5, it turns out that the queen on e6 is a poor blockader. White can underline this by 16.♘e2!, bringing the knight to f4. Black cannot stop this, since after 16…♘g6, there follows 17.h4!, with the idea of h4-h5.

Additional material

Svidler-Timofeev, Moscow 2004 – Black’s 25th move

Gulko-Karpov, Reykjavik 1991 – Black’s 18th move

Notkin-Malisauskas, Minsk 1997 – White’s 18th move

Makagonov-Boleslavsky, Moscow 1944 – Black’s 27th move

Hübner-Kasparov, Tilburg 1981 – Black’s 23rd move

Timman-Petrosian, Las Palmas 1982 – Black’s 13th move