Universal adult suffrage

Universal adult suffragePREVIEW

Elections are often seen as the practical face of democratic government. They are, in effect, democracy in action. When voters cast their ballots, they, rather than politicians or government, are ‘pulling the strings’. This is why, for instance, the suffragettes in the early years of the 20th century risked imprisonment, endured force-feeding and even sacrificed their lives to win the right to vote.

However, the closer we look at elections the more complicated they appear. The task of electing representatives can be done in a wide variety of ways, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. In fact, no fewer than five voting systems are currently in operation in different parts of the UK. Which of these systems is the best? Which one is the most democratic? Such issues are particularly controversial when they are applied to the oldest and most important voting system in the UK, the Westminster electoral system. As this is the system that is used for general elections, any change to it would affect almost every aspect of how the political system works.

Nevertheless, in recent decades, democratic government in the UK has acquired a second practical face, through the wider use of referendums. Whereas an election is essentially a means of filling a public office, a referendum is a vote on an issue of public policy. Although the former is an example of representative democracy, the latter is a device of direct democracy. However, why have referendums become more common in the UK? When and how should referendums be used? And should the wider use of referendums be encouraged or resisted?

CONTENTS

• Elections in the UK

• Functions of elections

- Forming governments

- Ensuring representation

- Upholding legitimacy

• Electoral systems

- First-past-the-post

- Majority systems

- Proportional systems

• Which electoral system is best?

- The electoral reform debate

• Referendums

- The wider use of referendums

- Scottish independence referendum

- EU referendum

Elections are central to the theory and practice of democracy in the UK. As we saw in the previous chapter, the UK’s claim to be a democracy is largely based on the nature of its electoral system, and the fact that UK elections are based on:

Universal adult suffrage

Universal adult suffrage

One person, one vote

One person, one vote

The secret ballot

The secret ballot

Competition between candidates and parties.

Competition between candidates and parties.

Election: A method of filling an office or post through choices made by a designated body of people: the electorate.

Elections are therefore the main link between government and the people, meaning that voting is the most important form of political participation. The opportunities to vote in the UK have, in fact, increased significantly in recent years. Since 2000, the electoral process in the UK has been regulated by the Electoral Commission (see p. 37).

The main elections in the UK are:

• General elections. These are full parliamentary elections, in which all the seats in the House of Commons come up for re-election (Westminster elections). They have traditionally taken place within a five-year maximum term, the date being decided by the prime minister, but the Conservative-led coalition changed these to five-year, fixed-term elections. (Earlier elections may nevertheless be called with the support of two-thirds of MPs.)

• Devolved assembly elections. These are elections to the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly and the Northern Ireland Assembly. They are fixed-term elections that take place every four years (first held in 1998 in Northern Ireland and in 1999 elsewhere).

• European Parliament elections. These are fixed-term elections that take place every five years (first held in 1979). However, as the UK will probably have left the EU by the time the next European Parliament elections are due in May 2019, the 2014 European Parliament election is likely to have been the last to involve the UK.

• Local elections. These are elections to district, borough and county councils. They include elections to the Greater London Assembly and for the London Mayor, with mayoral elections also taking place in some other local authorities. They are fixed-term elections that take place usually every four or five years.

However, what role do elections play in the political system? And in what sense do elected politicians ‘represent’ the people?

Differences between ...

Elections and Referendums

ELECTION • Fill office/form government • Vote for candidate/party • General issues • Regular (legally required) • Representative democracy |

REFERENDUM • Make policy decisions • Select yes/no option • Specific issue • Ad hoc (decided by government) • Direct democracy |

There are three main functions of elections. Elections serve to:

Form governments

Form governments

Ensure representation

Ensure representation

Uphold legitimacy.

Uphold legitimacy.

FORMING GOVERNMENTS

Elections are the principal way in which governments in the UK are formed. They therefore serve to transfer power from one government to the next. This is the function of a general election. In the UK, governments are formed from the leading members of the majority party in the House of Commons. As the results of the elections are usually clear (every general election since 1945, except those in February 1974 and May 2010, has produced a single, majority party), this usually takes place the day after the election. The leader of the majority party becomes the prime minister, and the prime minister’s first task is to appoint the other ministers in his or her government.

However, elections in the UK may not always be successful in forming governments:

• As is discussed later in the chapter, where proportional electoral systems are used it is less likely that a single ‘winning’ party emerges from the election. As May 2010 demonstrated, this can also occur (although less frequently) when non-proportional electoral systems are used. Governments may therefore be formed through deals negotiated amongst two or more parties after the election has taken place. These deals may take days and, potentially, weeks to negotiate.

Elections are also a vital channel of communication between government and the people. They carry out a representative function on two levels. First, they create a link between elected politicians and their constituents. This helps to ensure that constituents’ concerns and grievances are properly articulated and addressed (although this ‘constituency function’ may be carried out more effectively by some electoral systems than by others). Second, they establish a more general link between the government of the day and public opinion. This occurs because elections make politicians, and therefore the government of the day, publicly accountable and ultimately removable. Elections therefore give the people final control over the government.

Public opinion: Views shared by members of the public on political issues; the views of many or most voters.

However, doubts have also been raised about the effectiveness of elections in ensuring representation:

• Four- or five-year electoral terms, as usually found in the UK, weaken the link between voters and representatives. Five-year, fixed-term Parliaments, as introduced in the UK in 2011, are longer than the equivalent in many other liberal democracies, which is one of the reasons why the reform remains controversial (see p. 270).

• There is considerable debate about how elected politicians can and should ‘represent’ their electors. This is reflected in competing theories of representation (see p. 215).

Table 3.1 UK electoral systems

Voting system |

Where used |

Type |

‘First-past-the-post’ (FPTP) |

• House of Commons • Local elections in England |

Plurality system |

Additional member system (AMS) |

• Scottish Parliament • Welsh Assembly • Greater London Assembly |

Mixed system |

Single transferable vote (STV) |

• Northern Ireland Assembly • Local elections in Northern Ireland and Scotland |

Quota system |

Regional party list |

• European Parliament elections |

List system |

Alternative vote (AV) |

• Local by-elections in Scotland |

Majority system |

Supplementary vote (SV) |

• London mayoral elections |

Majority system |

As a political principle, representation is a relationship through which an individual or group stands for, or acts on behalf of, a larger body of people. Representation differs from democracy in that, while the former acknowledges a distinction between government and the people, the latter, at least in its classical sense, aspires to abolish this distinction and establish popular self-government. Representative democracy (see p. 32) may nevertheless constitute a limited and indirect form of democratic rule.

UPHOLDING LEGITIMACY

Elections play a crucial role in maintaining legitimacy. Legitimacy is important because it provides the key to maintaining political stability. It ensures that citizens recognise that they have an obligation to obey the law and respect their system of government. Elections uphold legitimacy by providing a ritualised means through which citizens ‘consent’ to being governed: the act of voting. Elections therefore confer democratic legitimacy on government.

However, elections in the UK may not always be successful in upholding legitimacy:

• Low turnout levels in general elections since 2001 have cast doubt on the legitimacy of the UK political system. Voter apathy may be a way in which disillusioned citizens are withholding ‘consent’.

• Falling support, since the 1970s, for the two ‘governing’ parties – Labour and the Conservatives – may indicate declining levels of popular satisfaction with the performance of the UK political system.

ELECTORAL SYSTEMS

Why do electoral systems matter? Electoral systems are not simply a collection of technical rules about how the electorate is organised and who they are able to vote for. More importantly, different electoral systems have different political outcomes – electoral systems make a difference. It is quite possible for a party to win an election under one set of rules, but to lose it under another set of rules. Similarly, one electoral system may produce a single-party government, while another would lead to coalition government. Electoral systems therefore have a major impact on political parties and on government, and therefore also on the quality of representation and the effectiveness of democracy.

For general purposes, the voting systems that are used in the UK can be divided into two broad categories on the basis of how they convert votes into seats:

• There are non-proportional systems, in which larger parties typically win a higher proportion of seats than the proportion of votes they gain in the election. This increases the chances of a single party gaining a parliamentary majority and being able to govern on its own.

• There are proportional systems, which guarantee an equal, or at least a close and reliable, relationship between the seats won by parties and the votes they gained in the election.

Non-proportional system: An electoral system that tends to ‘over-represent’ larger parties and usually results in single-party majority government.

Proportional system: An electoral system that tends to represent parties in-line with their electoral support, often portrayed as proportional representation.

FIRST-PAST-THE-POST

The main non-proportional voting system used in the UK is ‘first-past-the-post’, sometimes called FPTP or the single-member plurality system (SMP) (see p. 65). It is undoubtedly the most important electoral system used in the UK, as it is the system that is used for elections to the House of Commons and therefore it serves to form UK governments. Hence it is known as the Westminster electoral system.

‘First-past-the-post’ has the following implications:

Disproportionality

Disproportionality

Systematic biases

Systematic biases

Two-party system

Two-party system

Single-party government

Single-party government

The landslide effect.

The landslide effect.

Plurality: The largest number out of a collection of numbers; a ‘simple’ majority, not necessarily an ‘absolute’ majority.

Disproportionality

FPTP fails to establish a reliable link between the proportion of votes won by parties and the proportion of seats they gain. This happens because the system is primarily concerned with the election of individual members, not with the representation of political parties. An example of this is that it is possible with FPTP for the ‘wrong’ party to win an election. This is what happened in 1951, when the Conservatives formed a majority government but won fewer votes than Labour. In February 1974 the tables were turned, with Labour forming a minority government (as the largest party in the House of Commons) but with fewer votes than the Conservatives.

Used: House of Commons and in England and Wales for local government.

Features:

• It is a constituency system. Currently, there are 650 parliamentary constituencies in the UK.

• Voters select a single candidate, and do so by marking his or her name with an ‘X’ on the ballot paper. This reflects the principle of ‘one person, one vote’.

• Constituencies are of roughly equal size, which is ensured by reviews by the Electoral Commission and the Boundary Commissions for Scotland and Northern Ireland.

• Each constituency returns a single candidate. This is often seen as the ‘winner-takes-all’ effect. (However, there are still a small number of multimember constituencies in local government.)

• The winning candidate needs only to achieve a plurality of votes. This is the ‘first-past-the-post’ rule.

For example, if votes were cast as follows:

Candidate A = 30,000 votes

Candidate B = 22,000 votes

Candidate C = 26,000 votes

Candidate A would win, despite polling only 38 per cent of the vote.

(For advantages and disadvantages, see ‘Debating … Reforming Westminster elections’, p. 77.)

Constituency: An electoral unit that returns one or more representatives, or the body of voters who are so represented.

Systematic biases

However, the disproportionality of FPTP is not random. Certain parties do well in FPTP elections, while others suffer, sometimes dramatically. There are two kinds of bias:

• Size of party. Large parties benefit at the expense of small parties. This happens for three reasons:

• The ‘winner takes all’ effect means that 100 per cent of representation is gained in each constituency by a single candidate, and therefore by a single party.

• Winning candidates tend to come from large parties, as these are the parties whose candidates are most likely to be ‘first-past-the-post’, in the sense of winning plurality support. By contrast, candidates from small parties that come, say, third or fourth in the election win nothing and gain no representation for their party. This is a particular curse for so-called ‘third’ parties, which often come second behind one or other of two larger parties.

• Voters are discouraged from supporting small parties because they know that they are unlikely to win seats, and even more unlikely to win the overall election. This is the problem of so-called ‘wasted votes ’. A proportion of voters are therefore inclined to vote for large parties on the grounds that they are the ‘least bad’ of the two available, rather because they are their first preference party.

Wasted vote: A vote that does not affect the outcome of the election because it is cast for a ‘losing’ candidate or for a candidate who already has a plurality of votes.

• Distribution of support. Parties whose support is geographically concentrated do better than ones with evenly distributed support. This occurs because geographical concentration makes a party’s support more ‘effective’, in the sense that it is more likely to gain pluralities and thereby win seats. Similarly, such parties also have the advantage that where they are not winning seats they are ‘wasting’ fewer votes. The danger for parties with geographically evenly distributed support is that they come second or third in elections almost everywhere, picking up very few or perhaps no seats.

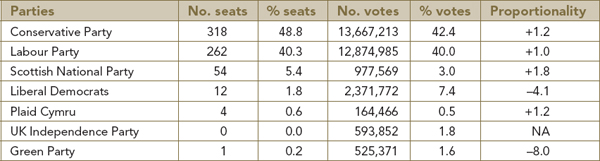

The Labour and Conservative parties have traditionally been ‘over-represented’ by FPTP because they have been both large parties and have tended to have geographically concentrated support thanks to the class basis of their voters (see Table 3.5, p. 80). The Liberal Democrats, by contrast, suffer the double disadvantage that they are smaller than the Labour and Conservative parties and also have less class-based and more geographically evenly spread support. In the case of the SNP and Plaid Cymru, the disadvantage of their being small parties is counter-balanced by their geographically concentrated support. Being small parties with relatively evenly spread support, UKIP and the Greens are clearly disadvantaged by the current system. The levels of proportionality and disproportionality that result from the use of FPTP can be illustrated by the outcomes of the general election of May 2015 (see Table 3.2).

Proportionality: The degree to which the allocation of seats among parties reflects the distribution of the popular vote. (This can be represented by the relationship between % seats and % votes.)

The 2015 general election nevertheless revealed a pattern of new or accentuated biases, beyond those that have traditionally advantaged Labour and the Conservatives, largely at the expense of the Liberal Democrats. In the first place, the surge in support for the SNP in Scotland meant that the benefit of geographical concentration ceased merely to counter-balance the effect of being a small party, but was so powerful that, for the first time, the party ended up being over-represented in the House of Commons. Indeed, in 2015, FPTP treated the SNP more favourably than any other party, including the Conservatives (the SNP’s proportionality rating was +1.8 compared with +1.4 for the Conservatives and +1.2 for Labour). Secondly, FPTP demonstrated a tendency towards dramatically heightened levels of disproportionality, as, due to its resolutely evenly spread support, UKIP’s only reward for more than quadrupling its vote since 2010 was a single seat (its proportionality rating was a remarkable –63). This created a situation in which, whereas it took 25,283 votes to elect a single SNP MP, it took almost 4 million votes to elect a single UKIP MP.

Table 3.2 General election results June 2017

Two-party system

An important implication of FPTP is a tendency for politics to be dominated by two ‘major’ parties. In other words, only two parties have sufficient parliamentary support to have a realistic chance of winning general elections and forming governments. Clearly, this happens as a result of the biases discussed above. Since the First World War, the UK has had a two-party system at Westminster, dominated by the Labour and Conservative parties. Although the proportion of votes gained by these parties has tended to fall, from over 95 per cent in the early 1950s to a low of 65 per cent in 2010, they have continued to have a stranglehold on the House of Commons. Even in 2010, 85 per cent of MPs belonged to either the Labour or Conservative parties. This tendency for UK politics to be a ‘two-horse race’ may, indeed, have further implications. For example, it may discourage potential supporters of ‘third’ parties from voting for them, thinking that such votes would be ‘wasted’ because they would not affect the outcome of the election. The problem of wasted votes is all the greater because Labour and the Conservatives each have ‘heartlands’ in which most seats are ‘safe’ seats. The outcome of a general election is therefore determined by what happens in a minority of seats, so-called ‘marginal’ seats. The key ‘marginals’ may number as few as 100 out of 650 seats.

‘Safe’ seat: A seat or constituency that rarely changes hands and is consistently won by the same party.

‘Marginal’ seat: A seat or constituency with a small majority, which is therefore ‘winnable’ by more than one party.

Single-party government

The most important consequence of a two-party system is that the larger of the ‘major’ parties usually wins sufficient support to be able to govern alone. In the UK, this means that it usually wins a majority of seats in the House of Commons. The other ‘major’ party forms the opposition and therefore acts as a kind of ‘government in waiting’. Not since 1935 has a party gained a majority of votes in a UK general election. However, only twice since then, in February 1974 and May 2010, has a party failed to gain a majority of seats in the House of Commons. Single-party government, in turn, has a wide range of consequences. Many of the arguments about electoral reform focus on the advantages of single-party government against those of coalition government (see p. 228).

Landslide effect

Not only does FPTP usually give the largest party majority control of the House of Commons, but it also tends to produce a ‘winner’s bonus’. This occurs as relatively small shifts in votes can lead to dramatic changes in the seats the parties gain. One of the consequences of this is that parties can win ‘landslide’ victories on the basis of relatively modest electoral support. This is a tendency that became particularly pronounced beween the early 1980s and the early 2000s. The decline in combined Labour–Conservative electoral support during this period created a situation in which a dramatic decline in the representation of the second ‘major’ party, resulted in an artificial ‘landslide’ victory for the winning party. This tendency was clearly evident in the 1983 general election (see p. 93) and the 1997 general election (see p. 96).

Used: Scottish local by-elections, Labour and Liberal leadership elections, and by-elections for hereditary peers.

Features:

• There are single-member constituencies.

• Electors vote preferrentially by ranking candidates in order (1, 2, 3 and so on).

• Winning candidates in the election must gain a minimum of 50 per cent of all votes cast.

• Votes are counted according to first preference. If no candidate reaches 50 per cent, the bottom candidate drops out and his/her votes are redistributed according to second or subsequent preferences, and so on, until one candidate gains 50 per cent.

Advantages:

• AV ensures that fewer votes are ‘wasted’ than in FPTP.

• As winning candidates must secure at least 50 per cent support, a broader range of views and opinions influence the outcome of the election, with parties thus being drawn towards the centre ground.

Disadvantages:

• The outcome of the election may be determined by the preferences of those who support small, possibly extremist, parties.

• Winning candidates may enjoy little first-preference support and only succeed with the help of redistributed supplementary votes, making them only the least unpopular candidate.

MAJORITY SYSTEMS

There are two other non-proportional electoral systems used in the UK, both of which are majority systems. These systems are:

• The alternative vote, or AV, is used for Australia’s lower chamber, the House of Representatives. It is used in the UK for local by-elections in Scotland and for various parliamentary purposes, including the election of the majority of chairs of select committees in the House of Commons. AV was decisively rejected as an alternative FPTP in a referendum in 2011.

• The supplementary vote, or SV (see p. 69), is a shortened version of AV. It has been used since 1999 for the election of the London mayor. Although both AV and SV commonly have more proportional outcomes than FPTP, the difference is marginal and, in some circumstances, they may be less proportional than FPTP.

Majority system: A voting system in which winning candidates must receive an overall majority (and not just a plurality) of votes to win a seat.

Used: London mayoral elections.

Features:

• Single-member constituencies.

• Electors have two votes: a first preference vote and a second, or ‘supplementary’, vote.

• Winning candidates in the election must gain a minimum of 50 per cent of all votes cast.

• Votes are counted according to first preference. If no candidate reaches 50 per cent, the top two candidates remain in the election and all other candidates drop out, their vote being redistributed on the basis of their supplementary vote.

Advantages:

• SV is ‘simpler’ than AV, and so would be easier for voters to understand and use.

• The focus on gaining second-preference or supplementary votes, encourages conciliatory campaigning and a tendency towards consensus.

Disadvantages:

• Although fewer votes are ‘wasted’ in SV compared with FPTP, unlike AV, SV does not ensure that the winning candidate has the support of at least 50 per cent of voters (because a proportion of supplementary votes will be for candidates who have dropped out).

• The emphasis on making supplementary votes count may encourage voters to support only candidates from the main parties, perhaps discouraging them from supporting their preferred second-preference candidate.

Figure 3.1 The proportional/non-proportional spectrum

The alternative vote and the supplementary vote have broadly been supported on the grounds that they address some of the flaws of FPTP while avoiding the pitfalls associated with proportional representation. In that sense, they are ‘middle ground’ voting systems. The experience of Australia, the principal country where AV is used, suggests that electoral outcomes are broadly similar to those achieved under FPTP. Larger parties and parties whose vote is geographically concentrated are typically over-represented in the Australian House of Representatives, while small parties are usually under-represented, especially when their support is geographically evenly spread. It is therefore little surprise that single-party majority government has been the norm in Australia. Nevertheless, although AV and SV are clearly non-proportional systems, their outcomes are commonly more proportional than FPTP’s, albeit marginally so. The Electoral Reform Society calculated that, had the 2015 general election been held under AV rules, the Liberal Democrats would have gained 9 seats rather than 8, and that the Conservative and Labour parties, combined, would have had one seat less.

Preferential voting, as employed by both AV and SV, usually also allows the systems to elect candidates only on the basis of majorities and not pluralities (although this may not be the case with SV, as some electors may allocate both of their votes to candidates who drop out). Finally, the distribution of second and subsequent preference votes can create electoral outcomes that appear to be anomalous. For instance, in over a third of Australian elections since 1945, the Liberal Party was awarded more seats than the Labor Party, despite having won fewer votes. Similarly, support for AV within the UK Labour Party is sometimes linked to the expectation that the system would favour Labour over the Conservatives, based on the belief that most Liberal Democrat voters would give their second-preference support to the former rather than the latter. In such circumstances, AV and SV could deliver more disproportional outcomes than FPTP.

PROPORTIONAL SYSTEMS

The other three electoral systems used in the UK broadly conform to the principle of proportional representation. These systems are:

• The additional member system (AMS) (see p. 71), sometimes called the mixed-member proportional system (MMP), is used for elections to the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly and the Greater London Assembly. As such, it is the second most significant electoral system in the UK after FPTP.

• The single transferable vote system, or STV (see p. 72), has been used since 1973 for local government elections in Northern Ireland. It is the system that has been used since 1998 to elect the Northern Ireland Assembly. It is also used for local elections in Northern Ireland and Scotland.

• The regional party list (see p. 73) has been used for elections to the European Parliament since 1999 (except in Northern Ireland, where STV is used). This brought the UK into line with the EU requirement that elections to the European Parliament should be proportional (even though the particular system used is left to each member state).

Proportional representation: The principle that parties should be represented in an assembly or parliament in direct proportion to their overall electoral strength.

Proportional voting systems have, to a greater or lesser extent, the following implications:

Greater proportionality

Greater proportionality

Multiparty systems

Multiparty systems

Coalition or minority government

Coalition or minority government

Consensus-building.

Consensus-building.

Used: Scottish Parliament, Welsh Assembly, Greater London Assembly.

Features:

• It is a ‘mixed’ system, made up of constituency and party-list elements.

• A proportion of seats are filled by ‘first past the post’, using single-member constituencies. In Scotland and London, 56 per cent of representatives are elected in this way. In Wales, this figure is 66 per cent.

• The remaining seats are filled using a ‘closed’ party-list system (see p. 73).

• Electors cast two votes: one for a candidate in a constituency election and the other for a party in a list election.

• The party-list element in AMS is used to ‘top up’ the constituency results. This is done ‘correctively’, using the D’Hondt method (devised by the Belgian mathematician Victor D’Hondt), to achieve the most proportional overall outcome.

Advantages:

• The mixed character of this system balances the need for constituency representation against the need for electoral fairness.

• Although the system is broadly proportional in terms of its outcomes, it keeps alive the possibility of single-party government.

• It allows voters to make wider and more considered choices. For example, they can vote for different parties in the constituency and list elections.

Disadvantages:

• The retention of single-member constituencies reduces the likelihood of high levels of proportionality.

• The system creates confusion by having two classes of representative.

• Constituency representation will be less effective than it is in FPTP, because of the larger size of constituencies and because a proportion of representatives have no constituency duties.

Greater proportionality

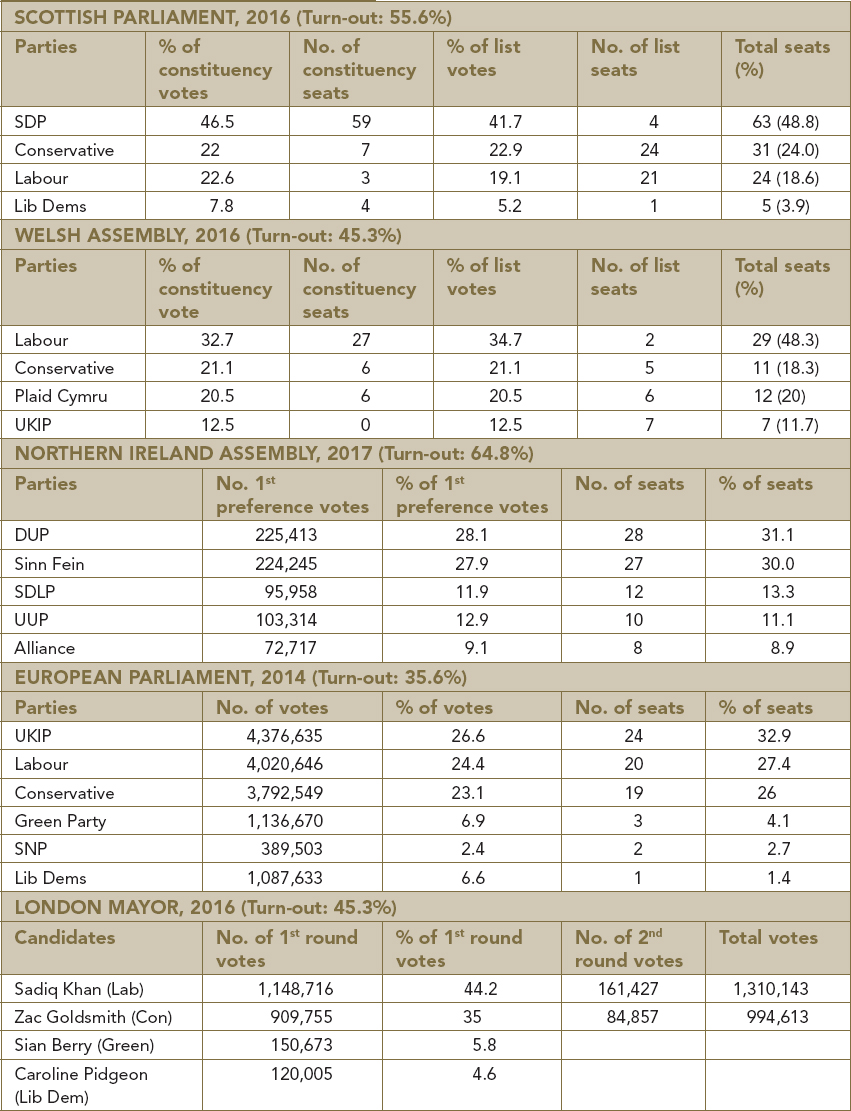

The regional party list, AMS and STV all deliver a high and reliable level of proportionality. The ‘over-representation’ of large parties and the so-called winner’s bonus or landslide effect of FPTP are absent, or greatly reduced, when these systems are used. For example, in the 2011 Scottish Parliament elections, although Labour won almost half the constituency seats (35 out of 73) on the basis of 32 per cent of the vote, its overall representation in the Scottish Parliament was ‘corrected’ by the distribution of party-list seats. This gave Labour 29 per cent of the total seats, leaving it in second place behind the Scottish National Party. Similarly, in the 2011 Welsh Assembly election Labour gained a clear majority of constituency seats (28 out of 40) with 42 per cent of the vote, but won only 43 per cent of the total seats in the Welsh Assembly because it gained only two regional seats.

Used: Northern Ireland Assembly, in Northern Ireland and Scotland for local government, and in Northern Ireland only for European Parliament.

Features:

• There are multimember constituencies. The Northern Ireland Assembly has 18 constituencies, each returning 6 members. In local elections in Northern Ireland there is a mixture of 5–6- and 7-member constituencies.

• Political parties are able to put up as many candidates as there are seats to fill in each constituency.

• Electors vote preferentially.

• Candidates are elected if they achieve a quota of votes. This quota is calculated on the basis of the Droop formula, as follows:

• Votes are counted, first, according to first preferences. If any candidate achieves the quota, additional votes for him or her are counted according to second or subsequent preferences.

• If this process still leaves some seats unfilled, the candidate with the fewest votes drops out and his or her votes are redistributed according to second or subsequent preferences.

Advantages:

• The system is capable of achieving highly proportional outcomes.

• Competition amongst candidates from the same party means that they can be judged on their individual records and personal strengths.

• The availability of several members means that constituents can choose who to take their grievances to.

Disadvantages:

• The degree of proportionality achieved in this system can vary, largely on the basis of the party system.

• Strong and stable single-party government is unlikely under STV.

• Multimember constituencies may be divisive because they encourage competition amongst members of the same party.

Multiparty systems

Minor parties that are denied representation by FPTP are more likely to win seats in the other voting systems. This substantially broadens the basis of party representation and creates multiparty systems. For example, until 2010 (when it won one seat), the Green Party had no representation at Westminster, despite having gained more than a quarter of a million votes in some previous general elections. However, the Greens were represented on most other bodies: two sit in the Scottish Parliament, two sit in the Greater London Assembly, and three sit in the European Parliament. The UK Independence Party (UKIP) won almost 4 million votes in the 2015 general election but gained only one seat. On the other hand, UKIP won 24 seats in the European Parliament in 2014, making it the largest UK party. Similarly, the Liberal Democrats, condemned for so long to ‘third’-party status at Westminster by the systematic biases of FPTP, have had greater representation where other voting systems are used, giving them, at times, considerable influence over devolved assemblies.

Used: European Parliament (except Northern Ireland where STV is used).

Features:

• There are a number of large multimember constituencies. For European Parliament elections, the UK is divided into 12 regions, each returning 3–10 members (72 in total).

• Political parties compile lists of candidates to place before the electorate, in descending order of preference.

• Electors vote for parties not for candidates. The UK uses ‘closed’ list elections.

• Parties are allocated seats in direct proportion to the votes they gain in each regional constituency. They fill these seats from their party list.

Advantages:

• It is the only potentially ‘pure’ system of proportional representation, and is therefore fair to all parties.

• The system tends to promote unity by encouraging electors to identify with a region rather than with a constituency.

• The system makes it easier for women and minority candidates to be elected, provided they feature on the party list.

Disadvantages:

• The existence of many small parties can lead to weak and unstable government.

• The link between representatives and constituencies is significantly weakened and may be broken altogether.

• Parties become more powerful, as they decide where candidates are placed on the party list.

Coalition or minority government

The tendency of more proportional voting systems to produce multiparty systems is also reflected in a greater likelihood of coalition governments or minority governments. This has tended to be found where all such electoral systems have been used in the UK. In the case of the Scottish Parliament, the SNP majority executive formed in 2011 is an exception, as the previous administrations were either Labour–Liberal Democrat coalitions or (in 2007) a minority SNP executive. In the case of the Welsh Assembly, Labour formed a brief minority executive after the 1999 election with a Labour–Liberal Democrat coalition executive being formed in 2000 and a grand coalition being formed in 2007 between Labour and Plaid Cymru. In 2011, Labour formed a single party government once again, but on the basis of just half of the seats in the Welsh Assembly. Although the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition at Westminster, formed in 2010, resulted from the use of FPTP, it, in effect, provided a laboratory which enables the implications of proportional representation to be studied.

Closed list: A version of the party-list system where voters only vote for political parties and have no influence over which individual candidates are elected, unlike ‘open’ lists.

Minority government: A government that does not have overall majority support in the assembly or parliament; minority governments are usually formed by single parties that are unable, or unwilling, to form coalitions.

Table 3.3 Election results beyond Westminster

A coalition is a grouping of rival political actors brought together through the recognition that their goals cannot be achieved by working separately. Coalition governments are formal agreements between two or more parties that involve a sharing of ministerial responsibilities. They are usually formed when no party has majority control of the legislature.

A ‘national’ government (sometimes called a ‘grand coalition’) comprises all major parties, but is usually formed only at times of national crisis (such as the National Governments which held office from 1931 until 1940). While supporters of coalition government highlight its breadth of representation and bias in favour of compromise and consensus-building, its critics warn that such governments tend to be weak and unstable.

Consensus-building

The shift from single-party majority government to coalition government led to a different style of policy-making (often described as the ‘new politics’) and to the adoption of different policies. In particular, whereas FPTP generally results in single-party governments that are supposedly able to ‘drive’ their policies through the House of Commons, other electoral systems foster a policy process that emphasises the need for compromise, negotiation and the development of a cross-party consensus. This occurs formally through the construction of coalition governments. Coalitions are usually based on post-election deals that share out posts in government and formulate legislation programmes that draw on the policy commitments of two or more parties. Consensus-building is also required in the case of single-party minority governments, which have to attract informal support from other parties in order to maintain control of Parliament. Policy, in either case, cannot be driven simply by the priorities of the leaders of a single party. This was evident when the 1974–79 Labour government lost its narrow majority and fell into minority status, forcing it to form a pact with the Liberal Party and to look for support to the SNP and Plaid Cymru. Among the policy adjustments this entailed was the first (albeit failed) attempt to introduce devolution. In the case of the 2010–15 Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition, the parties negotiated a joint programme of government and put in place an elaborate process to reconcile policy differences between them (as described in Chapter 9).

WHICH ELECTORAL SYSTEM IS BEST?

THE ELECTORAL REFORM DEBATE

The electoral reform debate in the UK has intensified since the mid-1970s. This was because of the revival in support for the Liberal Party and, later, the Alliance and the Liberal Democrats. Although more people voted for centre parties, these parties were unable to make an electoral breakthrough because of the biases implicit in the FPTP voting system. This was very clearly demonstrated in 1983, when the Alliance gained over one quarter of the vote but won only 23 seats, coming second in no fewer than 313 constituencies.

Electoral reform: A change in the rules governing elections, usually involving the replacement of one electoral system by another; in the UK the term is invariably associated with the reform of FPTP and the adoption of a PR system.

The prospects for electoral reform nevertheless brightened during the 1990s, as more and more members of the Labour Party were converted to the cause of PR following four successive defeats under FPTP rules. Growing sympathy towards electoral reform within the Labour Party was evident in two ways. First, Labour agreed that each of the devolved and other bodies that the party planned to introduce if it was returned to power would have a PR voting system. These new bodies, together with their various PR systems, were established from 1997 onwards. Second, Labour established an Independent Commission on the Westminster voting system, chaired by Lord Jenkins. The aim of the Jenkins Commission was to develop an alternative to FPTP that could be put to a public vote through a referendum. However, although the Commission reported in 1998, proposing the adoption of ‘AV Plus’, (in which AV is ‘topped up’ through the use of the party list system), the promised referendum was never held and the issue of electoral reform for Westminster elections was quietly forgotten.

Parties’ positions on electoral reform have always been closely linked to calculations about political advantage. The Conservative Party, the UK’s major party of government, has consistently opposed plans to reform an FPTP system that has only very rarely failed to ‘over-represent’ it. Labour, for its part, supported electoral reform for Westminster until 1945, when the party formed its first majority government, and its subsequent interest in electoral reform has tended to surface only when the party has been in opposition for a prolonged period or when it anticipates losing its majority at the next election. As a result, the prospects for electoral reform in the UK have always been linked to the possibility of a ‘hung’ Parliament, in which a ‘third’ party, until 2015 the Liberal Democrats, holds the balance of power.

‘Hung’ Parliament: A parliament in which no single party has majority control in the House of Commons.

This is precisely what occurred in 2010. The key aspect of the deal between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats through which the coalition government was formed was an agreement to hold a referendum on the introduction of AV for Westminster elections, with a commitment to impose a three-line whip on both parties in order to push the measure through the Commons in the event of a successful referendum. The decision to hold the AV referendum was clearly a compromise between the Liberal Democrats’ preference for the proportional STV system (which would almost have tripled their representation in 2010), and Conservative support for the retention of FPTP. Ironically, the only party that was committed to holding a referendum on AV in the 2010 election was the defeated Labour Party. AV has long been viewed as a possible alternative to FPTP in the UK. A Royal Commission in 1909–10 proposed that AV be used for elections to the House of Commons, but without success. A bill to introduce AV passed the Commons in 1917, but was rejected by the Lords and was eventually withdrawn. And an attempt by the minority 1929–31 Labour government to establish AV only failed when the government fell.

Debating ...

Reforming Westminster elections

FOR Electoral fairness. Fairness dictates that a party’s strength in Parliament should reflect its level of support in the country. Proportionality underpins the basic democratic principle of political equality. In PR, all people’s votes have the same value, regardless of the party they support. All votes count. In PR, no votes, or fewer votes, are ‘wasted’, in the sense that they are cast for candidates or parties who lose the election, or are surplus to the needs of winning candidates or parties. This should strengthen electoral turnout and promote civic engagement. Majority government. Governments elected under PR will enjoy the support of at least 50 per cent of those who vote. These will be genuinely popular, broad-based governments. By contrast, FPTP results in plurality rule. Parliamentary majorities can be gained with as little as 35 per cent of the vote, as occurred in 2005. Accountable government. PR has implications for the relationship between the executive and Parliament. FPTP leads to executive domination because a single party has majority control of the Commons. Under PR, governments have to listen to Parliament as they will generally need the support of two or more parties. Consensus political culture. PR electoral systems distribute political power more widely. As a wider range of parties are involved in the formulation of policy, decision-making becomes a process of consultation, negotiation and compromise. ‘Partnership politics’ therefore replaces ‘yaa-boo politics’. |

AGAINST Clear electoral choice. FPTP aids democracy because it clarifies the choices available to voters. It offers voters a clear and simple choice between potential parties of government, each committed to a different policy or ideological agenda. This makes elections and politics more meaningful to ordinary citizens. Constituency representation. FPTP establishes a strong and reliable link between a representative and his or her constituency. When a single MP serves a single constituency, people know who represents their interests and who should take up their grievances. Mandate democracy. In FPTP, voters get what they vote for: winning parties have the ability to carry out their manifesto promises. The doctrine of the mandate can therefore only operate in systems that produce single-party governments. Under PR, policies are decided through post-election deals not endorsed by the electorate. Strong government. FPTP helps to ensure that governments can govern. This happens because the government of the day enjoys majority control of the House of Commons. Coalition governments, by contrast, are weak and ineffective because they have to seek legislative support from two or more parties. Stable government. Single-party governments are stable and cohesive, and so are generally able to survive for a full term in office. This is because the government is united by common ideological loyalties and is subject to the same party disciplines. Coalition governments, by contrast, are often weak and unstable. |

AV has some clear advantages as an alternative to FPTP. These include that it would involve the simplest change, requiring no alteration to the established constituency structures. It can also be seen to maintain some of the alleged benefits of FPTP – a firm link between an MP and his or her constituency, and the possibility of strong and stable government, achieved through the existence of a single majority party – whilst at the same time increasing voter choice (through preferential voting) and ensuring that MPs enjoy at least 50 per cent support in their constituency. Under FPTP, this does not occur in about two-thirds of parliamentary constituencies and, exceptionally, as in Inverness in 1992, seats can be won with as little as 26.6 per cent of the vote. However, AV also has drawbacks. Chief amongst these is that it would create little prospect of greater proportionality, and may even result in less proportional outcomes (for instance, under AV, Labour’s majority in 1997 would have been 245 instead of 178).

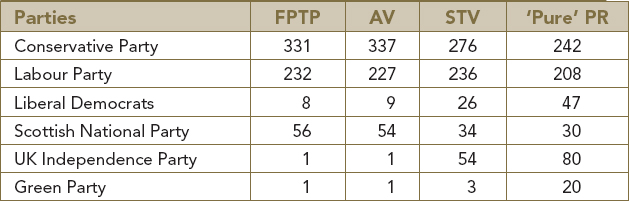

The defeat of the AV referendum in May 2011 brought to an end this attempt to reform the Westminster electoral system. In so doing, it appeared to damage badly the prospects for electoral reform in the near future. However, the outcome of the 2015 general election gave fresh impetus to the campaign for electoral reform, highlighting how poorly suited FPTP is to an era of multiparty politics. Condemned by the Electoral Reform Society (ERS) as a ‘blight on our democracy’, the 2015 election was the least proportional in British political history. UKIP and the Greens were grossly under-represented, while the SNP overtook both Labour and the Conservatives in becoming the most over-represented party. According to the ERS, this created a situation in which 24.2 per cent of seats in the Commons are held by MPs who would not be there if a proportional voting system were in place. The previous highest figure was 23 per cent in 1983, when the SDP–Liberal Alliance gained over a quarter of the vote but won a mere 3.5 per cent of seats. In 2010, the figure for MPs who would be displaced by PR was 21.8 per cent. The ERS analysis also showed that, of almost 31 million people who voted, 19 million (63 per cent of the total) did so for losing candidates. Out of the 650 winning candidates, 322 (49 per cent) won less than 50 per cent of the vote.

Table 3.4 Allocation of seats in 2015 election using different electoral systems

Source: Electoral Reform Society

However, would the reform of the Westminster voting system be a ‘good thing’? What is the best voting system? The simple fact is that there is no such thing as a ‘best’ electoral system. Each voting system is better at achieving different things: the real question is which of these things are the most important? The electoral reform debate is, at heart, a debate about the desirable nature of government and the principles that underpin ‘good’ government. Is representative government, for instance, more important than effective government? Is a bias in favour of compromise and consensus preferable to one that favours conviction and principle? There are no objective answers to these questions, only competing viewpoints.

REFERENDUMS

THE WIDER USE OF REFERENDUMS

The use of referendums was traditionally frowned upon in the UK. They were seen as somehow ‘not British’, because they conflicted with the principles of parliamentary democracy. Referendums diminished Parliament and undermined its popular authority. On the other hand, supporters of referendums argue that they have strong advantages over elections. These include allowing the public to make decisions directly, rather than relying on the ‘wisdom’ of professional politicians; and focusing on specific issues, rather than a broad set of policies. (See ‘Debating … Referendums’, p. 81.)

Key concept … REFERENDUM

A referendum (sometimes called a plebiscite) is a vote in which the electorate can express a view on a particular issue of public policy. It differs from an election in that the latter is essentially a means of filling a public office and does not provide a direct or reliable method of influencing the content of policy. The referendum is therefore a device of direct democracy.

Referendums may be either advisory or binding. They may be used to raise issues for discussion rather than to decide or confirm policy questions, in which case they have been called ‘propositions’. Whereas most referendums are called by the government, ‘initiatives’ (used especially in Switzerland and California) are a form of referendum that can be brought about by citizens.

Plebiscite: Literally, a popular vote; equivalent to a referendum.

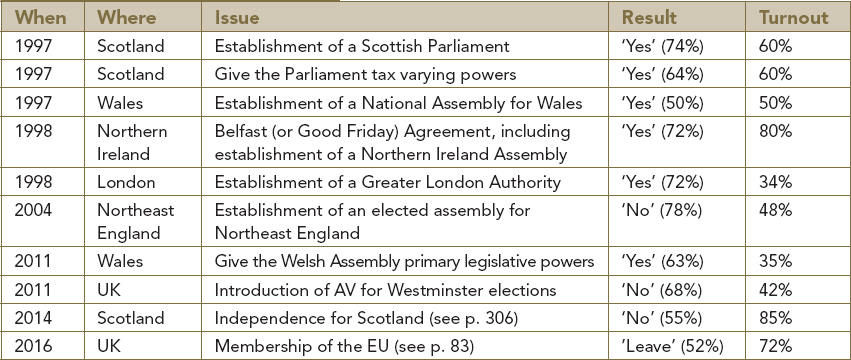

Table 3.5 Major referendums since 1997

Since 1997, referendums have been much more widely used in the UK. This has been because of the prominence of the issue of constitutional reform, especially in the period 1997–2001, and the growing acceptance that major changes to the way the UK is governed should be endorsed directly by the public rather than simply being left for Parliament to decide. This may, indeed, have created a new constitutional convention that major constitutional changes should in future always be put to a referendum. Nevertheless, some important referendums had been held before 1997. The most important one ever held in the UK (both in terms of its implications and the fact that it was the first UK-wide referendum) was the 1975 referendum on continued membership of the European Economic Community. This referendum also illustrated the fact that the decision to call a referendum is never unrelated to considerations of political advantage. For the then Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, the 1975 referendum was, in part, a device to hold together a Labour Party that was deeply divided over Europe. Referendums were also held in Scotland and Wales in 1979, in an unsuccessful attempt to introduce devolution.

The election in 2010 of a Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition gave renewed impetus to the use of referendums. The Coalition’s programme for government, published in May 2010 contained commitments to hold referendums on five issues. These were:

• The introduction of the alternative vote (AV) system for Westminster elections, in place of the ‘first-past-the-post’ system (carried out in May 2011)

• Any further transfer of power to Brussels (presumably through new EU treaties, in the event, no such treaties were introduced)

• Further Welsh devolution, specifically giving the Welsh Assembly primary legislative powers (carried out in March 2011)

• The creation of directly elected mayors in the 12 largest English cities (as of October 2016, 53 referendums had been held on the issue but only 16 had resulted in the establishment of elected mayors)

• The possibility of local referendums on any local issue, instigated by residents (this led to the introduction of the Localism Act 2011).

Debating ...

Referendums

FOR Direct democracy. Being a device of direct democracy, referendums give the general public direct and unmediated control over government decision-making. This ensures that the public’s views and interests are properly and accurately articulated, and not distorted by politicians who claim to ‘represent’ them. Political education. By widening the opportunities for political participation, and allowing debate to focus on a particular issue, referendums help to create a better informed, more educated and more politically engaged electorate. Members of the public have a stronger incentive to think and act politically. Responsive government. Referendums make government more responsive by forcing them to listen to public opinion between elections. Moreover, they allow public opinion to be expressed on a particular issue, something that is difficult to achieve via elections and impossible to achieve if all parties agree on an issue. Reduced government power. Referendums provide a much needed check on government power, because the government has less control over their outcome than it does over Parliament. Citizens are therefore protected against the danger of over-mighty government. Constitutional changes. It is particularly appropriate that constitutional changes should be popularly endorsed via referendums because constitutional rules affect the way the country is governed, and so are more important than ordinary laws. This also ensures that any newly created body has democratic legitimacy. |

AGAINST Ill-informed decisions. By comparison with elected politicians, the general public is ill-informed, poorly educated and lacks political experience. The public’s interests are therefore best safeguarded by a system of ‘government by politicians’ rather than any form of popular self-government. Weakens parliament. The use of referendums does not strengthen democracy; rather, at best, it substitutes direct democracy for parliamentary democracy. This not merely undermines the vital principle of parliamentary sovereignty (see p. 189), but also means that decisions are not made on the basis of careful deliberation and debate. Irresponsible government. Referendums allow governments to absolve themselves of responsibility by handing decisions over to the electorate. As governments are elected to govern, they should both make policy decisions and be made publicly accountable for their decisions. Strengthens government. Referendums may extend government power in a variety of ways. Not only do governments decide whether, when and over what issues to call referendums, they also frame the question asked (‘yes’ responses are usually preferred to ‘no’ responses) and can also dominate the publicity campaign. (However, such matters are now ‘policed’ by the Electoral Commission.) Unreliable views. Referendums provide only a snapshot of public opinion at one point in time. They are therefore an unreliable guide to the public interest. This also makes them particularly inappropriate for making or endorsing constitutional decisions, as these have long-term and far-reaching implications. |

Why did referendums once again become more common? Part of the answer was that the participation of the Liberal Democrats in the coalition ensured that there would be revived interest in the issue of constitutional reform; and, in the light of practice since 1997, there was an expectation that significant constitutional reforms would need to be publicly endorsed. The Liberal Democrats have also been more openly committed than either the Labour or Conservative parties to the use of referendums on principled grounds, linked to the promotion of democracy. However, these commitments on referendums were not merely a consequence of constitutional or principled considerations. Concerns about practical issues, notably those related to coalition management, were at least as important.

For example, in the case of the AV referendum, its attraction for Liberal Democrats was that it created the possibility that the ‘first-past-the-post’ electoral system could be replaced, whereas for many Conservatives the referendum had the advantage that a ‘no’ vote would allow ‘first-past-the-post’ to survive. Similarly, support in the Conservative Party for a referendum on any further transfer of power to Brussels was based on the desire to slow down, or block, the process of European integration, by imposing a so-called ‘referendum lock’ that would prevent a UK government from ratifying an EU treaty without holding a referendum. Liberal Democrats, on the other hand, had generally favoured the idea of such referendums on the grounds that they may help to build public support for further EU integration. In other words, the Coalition partners may have been united in their desire to hold a referendum, but were divided over the desired outcome. The referendum had therefore, once again, served as a mechanism for holding together a divided governing party or, in this case, a coalition government containing rival goals or aspirations.

SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE REFERENDUM

However, neither of the two most significant referendums held since 2010 had been anticipated in the programme for government. These were the September 2014 referendum on Scottish independence (see p. 306) and the June 2016 referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU (see p. 83). The former was the third major referendum to have been held in Scotland, but the first to be held on the issue of independence. A referendum had been held in 1979 on Scottish devolution. This failed because, although it was backed by a narrow majority, the ‘yes’ vote fell short of the then-required minimum of 40 per cent of the Scottish electorate. In 1997, a second devolution referendum was nevertheless successful, preparing the way for the establishment of the Scottish Parliament. As support for the Scottish National Party (SNP) subsequently grew, enabling it in 2007 to form a minority administration and then in 2011 to win an overall majority, the SNP shifted its focus from calling for a further referendum to widen the powers of the Scottish Parliament to demanding an independence referendum. This led in 2012 to the Edinburgh Agreement, under which the Scottish and UK governments agreed to hold an independence referendum two years later. Although David Cameron was, at the time, criticised by some in his own party for being ‘over-fair’ to the SNP government in these negotiations – agreeing, among other things, that the Scottish Parliament should provide the legislative basis for the referendum, as well as determining its franchise, timing and wording – his judgement, as a Unionist, was eventually proved to be correct, 55 per cent of the Scottish electorate voting ‘no’ in the eventual referendum.

EU REFERENDUM

However, Cameron’s judgement was spectacularly less reliable in the case of the 2016 EU referendum. When, in January 2014, Cameron committed his party to holding an ‘in/out’ referendum on EU membership before the end of 2017, provided the Conservatives won in the 2015 general election, he did so against the backdrop of growing Euroscepticism on his backbenches. Although resurgent Euroscepticism certainly had the capacity to embarrass the prime minister and damaged the image of the Conservative Party, it did not threaten the fall of either Cameron or the Coalition. By promising to hold an EU referendum, Cameron hoped both to restore his authority over his party by quelling the rebellion over Europe and to improve the chance of a Conservative victory in 2015 by undermining the UK Independence Party. The referendum was thus a referendum of choice, a referendum of calculation. The core calculation was, nevertheless, that (if it were held) the referendum would end up endorsing, rather than rejecting, EU membership, especially as defeat in the referendum would almost certainly spell the end of Cameron’s political career.

Cameron and key advisers were confident of a positive outcome from the referendum for two reasons. First, the referendum campaign was expected to be an unequal struggle between, on the one hand, virtually the entire UK political establishment, including the leaderships of all the major Westminster parties, backed by the bulk of business leaders, senior economists, trade union bosses and the like, and, on the other hand, UKIP and ‘fringe’ figures in the Conservative Party. Second, despite the recognition that the EU was broadly unloved, there was an expectation that, faced with the prospect of profound and irreversible change, the UK electorate would ‘stick with the devil they know’. This, after all, had been the lesson of both the AV and Scottish independence referendums. In the event, both of these expectations were confounded. The ‘Leave’ campaign was bolstered by the recruitment of senior figures such as Michael Gove and Boris Johnson to their cause, as well as by Jeremy Corbyn’s seemingly equivocal support for ‘Remain’, and the 52 per cent victory for ‘Leave’ in June 2016 showed that the prospect of change can sometimes be more attractive than the comforts of the status quo (see ‘The rise of anti-politics’, p. 46).

THE EU REFERENDUM

The UK woke up on 24 June 2016 having made its most important political decision (probably) since 1945. For good or ill, the 52 per cent ‘Leave’ victory in the referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union (EU) will affect the country for decades to come, having an impact on matters ranging from economic performance and the constitution to the UK’s place in the world and the survival of the UK as a single entity. However, controversy also surrounded the EU referendum in terms of how the decision was made, and, specifically, whether a plebiscite or popular vote was the right way to settle the issue. What light does the EU referendum cast on the wider issue of whether, when and how to use referendums?

Those who applaud the use of the referendum in this circumstance argue that the EU referendum explodes the myth that referendums are typically mechanisms through which governments and political leaders manipulate political outcomes behind a smokescreen of direct democracy. Although Cameron’s 2013 promise to hold a referendum on EU membership began life as an exercise in party management, it gradually turned into something very different and increasingly beyond his control. The electorate, in short, declined to play its assigned role. The EU referendum was very much an example of democracy in the raw. Settling the UK’s relationship to the EU through a referendum, rather than a parliamentary debate, was the only way that widespread and growing popular hostility towards the EU could reliably be articulated. Otherwise, public opinion would have been blocked or ‘sanitised’ due to pro-EU majorities in each of the major Westminster parties. For the electorate, the referendum itself, and not merely its outcome, was thus a means of ‘regaining control’, as the ‘Leave’ campaign slogan put it.

Serious reservations have been expressed about the EU referendum, however. Perhaps the most important of these was that the issue of EU membership was far too complex and far-reaching to allow ordinary citizens (and many experts, for that matter) to reach a balanced and evidence-based judgement. This left them prey to misinformation and exaggeration, and increased the chances that the outcome would be determined by quite different factors (in this case, perhaps, the desire to punish the political elite). Moreover, to boil the question of EU membership down to a simple choice between ‘Remain’ and ‘Leave’ was (at best) unhelpful and, in the absence of a plan for Brexit, virtually meaningless. Finally, the EU referendum highlighted the danger that, because (unlike parliamentary democracy) direct democracy is unchecked by the need for debate and deliberation, it may unleash ‘dark’ forces in the form of populism (see p. 137) and the politics of simple solutions.

SHORT QUESTIONS:

1 What is an election?

2 Distinguish between elections and referendums.

3 What is representation?

4 Identify two features of the ‘first-past-the-post’ electoral system.

5 Define proportional representation.

6 What is an initiative?

7 Why are referendums seen as an example of direct democracy?

MEDIUM QUESTIONS:

8 Explain the link between election and legitimacy.

9 How do elections ensure representation?

10 Explain three ways in which the elections promote democracy.

11 Explain the workings of any three electoral systems used in the UK.

12 How does ‘first-past-the-post’ differ from the other electoral system used in the UK?

13 Why are marginal seats more important under the ‘first-past-the-post’ system?

14 Why have referendums been more widely used since 1997?

15 Why has it been alleged that referendums tend to strengthen government power?

EXTENDED QUESTIONS:

16 To what extent do different electoral systems affect party representation and government?

17 Should proportional representation be used for Westminster elections?

18 Make a case against reforming the electoral system used for UK general elections.

19 To what extent has the use of more proportional electoral systems affected the political process in the UK?

20 ‘Referendums have more democratic authority than elections.’ Discuss.

21 Assess the claim that all significant constitutional reforms should be ratified by a referendum.

22 Is a referendum verdict ever challengeable?