In order to scrub up his image (and possibly assuage his conscience), John D. hired Ivy Lee, the nation’s most prestigious ad man of the day. Lee suggested that the aging gentleman offset his skinflint image by starting to give away money. Scrooge was to be turned into an instant Santa Claus. To begin with, Lee (the original Madison Avenue truth-twister) had Mr. Standard Oily carry around a pocketful of dimes which he would strew before deliriously happy and grateful kiddies whenever he made one of his infrequent public appearances. Cynics observed that St. John ripped off money by the millions and doled it back a dime at a time.

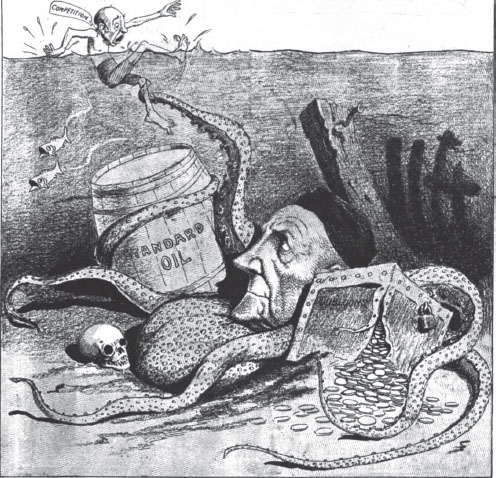

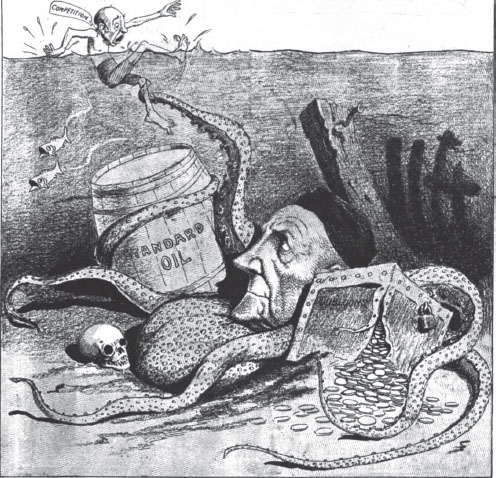

The real menace of our Republic is the invisible government, which like a giant octopus sprawls its slimy legs over our cities, states, and nation.

IN 1909, THE Department of Justice filed a lawsuit charging that Standard Oil represented an illegal monopoly by violating the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act in a variety of ways, including “rebates, preferences, and other discriminatory practices by railroad companies; restraint and monopolization by control of pipe lines, and unfair practices against competing pipe lines; contracts with competitors in restraint of trade; unfair methods of competition, such as local price cutting at the points where necessary to suppress competition; [and] espionage of the business of competitors, the operation of bogus independent companies, and payment of rebates on oil, with the like intent.”1

The suit maintained that these offenses took place not only during the Oil War of 1872 but also within the past four years (1905–1909). It charged the following: “The general result of the investigation has been to disclose the existence of numerous and flagrant discriminations by the railroads in behalf of the Standard Oil Company and its affiliated corporations. With comparatively few exceptions, mainly of other large concerns in California, the Standard has been the sole beneficiary of such discriminations. In almost every section of the country that company has been found to enjoy some unfair advantages over its competitors, and some of these discriminations affect enormous areas.”2

The Justice Department singled out four illegal patterns: (1) secret and semisecret railroad rates; (2) discriminations in the open arrangement of rates; (3) discriminations in classification and rules of shipment; (4) discriminations in the treatment of private tank cars. The suit alleged:

Almost everywhere the rates from the shipping points used exclusively, or almost exclusively, by the Standard are relatively lower than the rates from the shipping points of its competitors. Rates have been made low to let the Standard into markets, or they have been made high to keep its competitors out of markets. Trifling differences in distances are made an excuse for large differences in rates favorable to the Standard Oil Co., while large differences in distances are ignored where they are against the Standard. Sometimes connecting roads prorate on oil—that is, make through rates which are lower than the combination of local rates; sometimes they refuse to prorate; but in either case the result of their policy is to favor the Standard Oil Co. Different methods are used in different places and under different conditions, but the net result is that from Maine to California the general arrangement of open rates on petroleum oil is such as to give the Standard an unreasonable advantage over its competitors.”3

The government concluded its case against Standard Oil by saying: “The evidence is, in fact, absolutely conclusive that the Standard Oil Co. charges altogether excessive prices where it meets no competition, and particularly where there is little likelihood of competitors entering the field, and that, on the other hand, where competition is active, it frequently cuts prices to a point which leaves even the Standard little or no profit, and which more often leaves no profit to the competitor, whose costs are ordinarily somewhat higher.4

On May 15, 1911, the United States Supreme Court agreed that Standard Oil was “an open and enduring menace to all freedom of trade and a byword and reproach to modern economic methods.”5 John D. was now compelled to break down his monopoly into a host of smaller, independent companies. Strange to say, what should have been a setback for Rockefeller was actually an enormous stroke of good fortune. The antitrust decision turned him into the world’s first billionaire.6 His companies would become omnipresent. Standard Oil of New Jersey became Exxon; State Oil of New York—Mobil; State Oil of Indiana—Amoco; Standard Oil of California—Chevron; Atlantic Refining—ARCO and eventually Sunoco; and Continental Oil—Conoco.7

On May 15, 1911, the United States Supreme Court agreed that Standard Oil was “an open and enduring menace to all freedom of trade and a byword and reproach to modern economic methods.”

When the Supreme Court decision was made, it remained somewhat doubtful that automobiles would become a mainstay of the oil industry. Ethyl alcohol had been used as a fuel source since the early years of the 19th century, and Henry Ford believed that the Model T, which he was mass-producing in Detroit, would prove to be an enormous boon for farmers. Ford said to a reporter from the New York Times: “The fuel of the future is going to come from fruit like that sumach [sic] out by the road, or from apples, weeds, sawdust—almost anything. There is fuel in every bit of vegetable matter that can be fermented.”8

When Ford made this prediction, the Model T was manufactured in a variation that allowed drivers to switch the carburetor to run the engine on ethanol. This modification allowed drivers to stop at local farms, equipped with stills, to refuel their cars during trips through the country.9

Believing Ford that crops could provide America’s fuel for the future, farmers throughout the country lobbied Congress to repeal the $2.08 per gallon tax on alcohol that had been in effect since the Civil War. In support of the repeal, President Teddy Roosevelt addressed Congress and said: “The Standard Oil Company has, largely by unfair or unlawful methods, crushed out home competition. It is highly desirable that an element of competition should be introduced by the passage of some such law as that which has already passed the House, putting alcohol used in the arts and manufactures upon the free list.”10

The alcohol tax was repealed, and corn ethanol at 14 cents a gallon became considerably cheaper than a gallon of gasoline at 22 cents.11 The promise of a new, inexpensive fuel that could be produced from raw vegetables electrified the agricultural industry. Throughout the country, farmers allocated more and more of their fields for corn that could be fermented into fuel for cars and trucks that were rapidly becoming omnipresent.

Alarmed by these developments, Rockefeller pumped the equivalent of $60 million into groups supporting Prohibition, including the Women’s Christian Temperance League, and thereby became the driving force behind the movement to ban the production and sale of alcohol.12

When the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect on January 16, 1920, farmers were compelled to add poison to their alcohol, and their stills fell under the surveillance of the 1,520 Prohibition officers.13 Ethanol became too expensive and troublesome to produce, and Rockefeller had managed to secure his monopoly.

The fortune of the Rockefeller family expanded throughout the 20th century beyond the wildest imagination of Ida Tarbell or any of John D.’s critics. By 1976, when America celebrated its bicentennial, the Rockefellers owned 25 percent of all the assets of the world’s 50 largest commercial banks and 30 percent of the assets of all the insurance companies. In addition, the family held controlling interest in Exxon, Mobil Oil, Standard Oil of California (ChevronTexaco), Standard Oil of Indiana (Amoco), International Harvester, Inland Steel, Marathon Oil, Quaker Oats, Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel, Freeport Sulfur, and International Basic Economy Corporation.14

When the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect on January 16, 1920, farmers were compelled to add poison to their alcohol, and their stills fell under the surveillance of the 1,520 Prohibition officers.

Through trust departments and the Rockefeller Foundation, the family held the single largest block of stock in United Airlines, Northwest Airlines, Long Island Lighting, Atlantic Richfield, National Airlines, Delta, Braniff, Consolidated Freightways, IBM, IT&T, Westinghouse, Boeing, International Paper, Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing, Sperry Rand, Xerox, National Cash Register, National Steel, American Home Products, Pfizer, Avon, and Merck. Other corporations in which the Rockefellers possessed significant shares were AT&T, Motorola, Safeway, Honeywell, General Foods, Hewlett-Packard, and Burlington Industries.15 Corporations that maintained interlocking directorates with the Rockefeller Group included Allied (Chemical), Anaconda Cooper, DuPont, Monsanto, Olin Matheson, National Distillers, Shell, Gulf, Union Oil, Dow Chemical, Celanese, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Cities Service, Stauffer Chemical, Continental Oil, Union Carbide, American Cyanamid, Chrysler, C.I.T. Financial, S. S. Kresge, and R. H. Macy.16

These holdings were discovered in 1975. At present, it is impossible to discern the full extent of the Rockefellers’ control of major banks, and corporations throughout the world since the holdings of the family are held in trust with “street names” that are totally fictitious.

In addition to the monumental control that the Rockefellers wielded over America’s private-sector banks and businesses, the family, according to economist Eustace Mullins, held the lion’s share of stock in the Federal Reserve System.17 This development occurred as a result of John D.’s association with J. P. Morgan, his ties to the House of Rothschild, and his membership in the Pilgrim Society. Only by the House of Rockefeller’s acquisition of such power and might could the killing of the planet get underway.

1 Leslie D. Manns, “Dominance in the Oil Industry: Standard Oil from 1865 to 1911,” in Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose It and the Impact on Economic Performance, ed. David I. Rosenbaum (New York: Praeger, 1998), p. 11.

2 Eliot Jones, The Trust Problem in the United States (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1923), pp. 89–90.

3 Ibid, pp. 75–76.

4 Ibid., p. 80.

5 United States vs Standard Oil, Legal Information Institute, Cornell University, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/221/1, accessed January 17, 2019.

6 James Corbett, “How and Why Big Oil Conquered the World,” The Corbett Report, October 6, 2017, https://www.corbettreport.com/bigoil/, accessed January 17, 2019.

7 Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (New York: Vintage Books, 1998), pp. 558–59.

8 Henry Ford, quoted in Corbett, “How and Why Big Oil Conquered the World.”

9 “The Great Scheme: Alcohol-Based Fuels, Ford, Rockefeller, and Prohibition,” Serendipity, June 26, 2007, dgrim.blogspot.com/2007/06/great-scheme-alcohol-based-fuels-ford.html, accessed January 17, 2019.

10 Teddy Roosevelt, quoted in Corbett, “How and Why Big Oil Conquered the World.”

11 Ibid.

12 “Prohibition Sponsored by Standard Oil,” Snopes, November 29, 2008, message.snopes.com/showthread.php?t=38995, accessed January 17, 2019.

13 Benjamin Elisha Sawe, “What Was Prohibition in the United States?” World Atlas, April 25, 2017, https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-was-prohibition-in-the-united-states.html, accessed January 17, 2019.

14 Gary Allen, The Rockefeller File (Seal Beach, CA: ’76 Press, 1976), pp. 31–32.

15 Ibid., pp. 32–33.

16 Ibid., p. 34.

17 Eustace Mullins, The Secrets of the Federal Reserve (New York: Kasper and Horton, 1982), http://www.jrbooksonline.com/PDF_Books/SecretsOfFedReserve.pdf, accessed January 17, 2019.