Is there no danger to our liberty and independence in a bank that in its nature has so little to bind it to our country? The president of the bank has told us that most of the State banks exist by its forbearance. Should its influence become concentered, as it may under the operation of such an act as this, in the hands of a self-elected directory whose interests are identified with those of the foreign stockholders, will there not be cause to tremble for the purity of our elections in peace and for the independence of our country in war? Their power would be great whenever they might choose to exert it; but if this monopoly were regularly renewed every fifteen or twenty years on terms proposed by themselves, they might seldom in peace put forth their strength to influence elections or control the affairs of the nation. But if any private citizen or public functionary should interpose to curtail its powers or prevent a renewal of its privileges, it can not be doubted that he would be made to feel its influence.

Should the stock of the bank principally pass into the hands of the subjects of a foreign country, and we should unfortunately become involved in a war with that country, what would be our condition? Of the course which would be pursued by a bank almost wholly owned by the subjects of a foreign power, and managed by those whose interests, if not affections, would run in the same direction there can be no doubt. All its operations within would be in aid of the hostile fleets and armies without. Controlling our currency, receiving our public moneys, and holding thousands of our citizens in dependence, it would be more formidable and dangerous than the naval and military power of the enemy.

DESPITE THE DISSOLUTION of the Bank of the United States and the need for some regulation over America’s burgeoning economy, Congress refused to assert the power granted to them by Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution “to coin money and regulate the value thereof.”1 To make matters worse, they granted this power to state-chartered corporations, who proceeded to produce as much paper currency as a colonial press could produce. The glut of money flowed from the fact that these corporations charged interest on every dollar that they produced. Since the States were not actually producing currency, but rather chartering companies to perform the task, the state and federal legislations managed to skirt the implicit Constitutional provision (Article I, Section 10) that prohibited state governments from coining money, emitting bills of credit, or making anything but gold and silver coin a legal tender for the payment of debts.2

The grim financial situation was worsened by the War of 1812. This conflict erupted because of Britain’s attempts to restrict trade between the United States and France and the impression of American seamen into British service. By the time that war had been declared, 400 U.S. ships had been impounded by the British fleet; their cargo was impounded; and 6,000 sailors were declared to be British subjects and forced into the service of the Royal Navy.3

With the war raging, the banks continued to churn out as much paper money as they could print to purchase government bonds. These bonds were used to purchase war munitions, including ships and cannons. The national debt soared from $45 million to $127 million, a crippling sum for the new nation. Tripling the money supply without an appreciable increase in goods meant that the dollar lost more than one-third of its purchasing power. This devaluation caused a massive run on the banks as more and more Americans sought to redeem their paper certificates for gold or silver. Since the banks lacked the reserves to meet the demand for specie (tangible assets), armed guards were hired to protect bank officials from angry crowds in cities throughout the country.4

In 1811, when the charter for First National was set to expire, “Natty” Rothschild, the new head of the family, issued this order: “Either the application for renewal of the charter is granted, or the United States will find itself in a disastrous war.”5 While the actual role of the banking family in instigating the war remains unknown, the Rothschilds provided the British government with loans without interest for the war effort.6 They also had solicited the services of Nicholas Biddle, who had acted as secretary to John Armstrong, the U.S. Ambassador to France from 1804 to 1810. In France, Biddle, who was a financial prodigy, gained the attention of James de Rothschild, who made him the family’s new point man in America.7 When he returned to the States, Biddle became a close advisor to President Madison and pressed for the war with England. His influence with the Madison administration intensified when Armstrong became Secretary of War in 1812.8

At the end of the struggle, America may have won its second war of independence, but the country was left with a huge war debt of $105 million relative to a population of eight million.9 Faced with this financial burden, Congress approved the creation of the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. To no one’s surprise, the Rothschilds emerged as the major shareholders.10

Nicholas Biddle, at the instigation of the Rothschild family, was appointed president of Second National, which opened a string of branches in every major city. These branches extended loans to businessmen, banks, farmers, and settlers who wished to purchase land in the American West. In 1819, the Second Bank drastically reduced the money supply. Loans were no longer available. Thousands of Americans suddenly discovered that they were unable to pay off their bank debts. Farmers were forced into foreclosure. Businesses went belly up. Speculators and settlers lost their land and savings. The widespread financial disaster and depression, which provoked popular resentment against banking and business enterprise, enabled the shareholders of Second National, namely the Rothschilds, to purchase enormous assets at greatly depressed prices.11

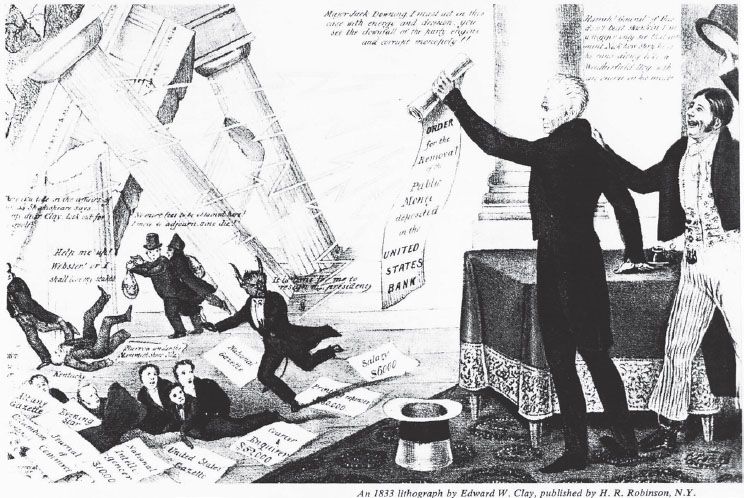

In 1828, Andrew Jackson ran for president with the slogan, “Jackson and No Bank.” The slogan was in keeping with his plan to seize control of the currency and to end the profiteering of the Rothschilds. As soon as he assumed the oath of office, Jackson began to withdraw government money from the Second Bank to deposit it in state banks. This action prompted the Rothschilds to contract the money supply and to create another depression. Jackson, who was known for his fiery temper, responded by swearing: “You are a den of thieves and vipers, and I intend to rout you out. If the people understood the rank injustices of our money and banking system, there would be a revolution before morning.”

Rout the Rothschilds, Jackson did. On September 10, 1833, he revoked the charter for the Second Bank five years before it was set to expire. In defense of his action, Jackson condemned the legislation that brought the bank into existence by saying:

The Act seems to be predicated on an erroneous idea that the present shareholders have a prescriptive right to not only the favor, but the bounty of the government…for their benefit does this Act exclude the whole American people from competition in the purchase of this monopoly. Present stockholders and those inheriting their rights as successors be established a privileged order, clothed both with great political power and enjoying immense pecuniary advantages from their connection with government. Should its influence be concentrated under the operation of such an Act as this, in the hands of a self-elected directory whose interests are identified with those of the foreign stockholders, will there not be cause to tremble for the independence of our country in war…controlling our currency, receiving our public monies and holding thousands of our citizens independence, it would be more formidable and dangerous than the naval and military power of the enemy. It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government for selfish purposes…to make the rich richer and more powerful. Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by acts of Congress. I have done my duty to this country.12

In 1828, Andrew Jackson ran for president with the slogan, “Jackson and No Bank.”

On January 30, 1835, Richard Lawrence, an English immigrant, attempted to shoot President Jackson in front of the Capitol building. His pistols misfired, and the President clubbed Lawrence to the ground with his cane. The would-be assassin was deemed mentally unsound and confined to an asylum for the criminally insane. Jackson said that the Rothschilds were responsible for the attempt on his life, and Lawrence insisted that he had been commissioned to commit the murder by a group of “powerful people in Europe.”13

The Rothschilds may have been routed, but they still cast their greedy eyes on the expanding new nation that was beginning to emerge as a leading industrial power. Their desire grew when Nathan Rothschild joined with Cecil John Rhodes to form the Society of the Elect. The notion of this secret society came from a brainstorm that struck Rhodes on June 2, 1877, the day he became a lifetime member of the Oxford University Apollo Chapter of the Masonic Order. Rhodes recorded his revelation as follows in his “Confession of Faith”: “The idea gleaming and dancing before one’s eyes like a will-of-the-wisp at last frames itself into a plan. Why should we not form a Secret Society with but one object the furtherance of the British Empire and the bringing of the whole uncivilized world under British rule for the recovery of the United States for the making the Anglo-Saxon race but one Empire.”14

As soon as he assumed the oath of office, Jackson began to withdraw government money from the Second Bank to deposit it in state banks. This action prompted the Rothschilds to contract the money supply and to create another depression.

After recruiting the most influential and wealthy individuals in England, Rothschild and Rhodes set out to forge this New World Order by initiating the Second Boer War in South Africa. By the time this bloody conflict came to an end in 1902, 7,582 British soldiers had been killed in action, 13,139 died of disease, 40,000 were wounded, and one had been eaten by a crocodile.15 Six thousand Boers were killed in action, while 26,000 white civilians and 17,182 African natives died of disease and starvation in concentration camps that had been set up in the Cape and Orange River colonies.16

After recruiting the most influential and wealthy individuals in England, Rothschild and Rhodes set out to forge this New World Order by initiating the Second Boer War in South Africa.

Rhodes and Rothschild gained complete control of the gold and diamond mines in South Africa, and the Transvaal and the Orange Free State became incorporated into the British Empire under Alfred Milner, who became the Society’s new leader. “De Kaap Gold Fields, South Africa: miners of the Republic Go” is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The war for the Society of the Elect produced salubrious efforts. Rhodes and Rothschild gained complete control of the gold and diamond mines in South Africa, and the Transvaal and the Orange Free State became incorporated into the British Empire under Alfred Milner, who became the Society’s new leader.17

The next step in achieving the Society’s objective was the reestablishment of a new centralized bank in America that would be yoked to the Bank of England. This would be accomplished by the Pilgrim Societies that had been established in London and New York and the alliance that had been forged by the Rothschilds’ creation of the great industrial empires of Andrew Carnegie, J. P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller.

1 George Leef, “After a Century of the Fed, It’s Time to Return to Constitutional Money,” Forbes, February 11, 2014, https://www.forbes.com/sites/georgeleef/2014/02/11/after-a-century-of-thefed-its-time-to-return-to-constitutional-money/#166f987a7a0f, accessed January 17, 2019.

2 Ibid.

3 Lonnae O’Neal Parker, “Maryland’s Historical Society’s 1812 Exhibit Captures a War’s Ambiguities,” Washington Post, June 7, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/maryland-historical-societys-1812-exhibit-captures-a-wars-ambiguities/2012/06/07/gJQASXowLV_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.5fb68e865f7d, accessed January 17, 2019.

4 G. Edward Griffin, The Creature from Jekyll Island, 5th ed. (Westlake Village, CA: American Media, 2014), p. 338.

5 Andrew Hitchcock, “The History of the House of Rothschild,” Rense.com, October 31, 1999, http://rense.com/general88/hist.htm, accessed January 17, 2019.

6 Ibid.

7 Patrick Carmack and William Still, The Money Masters: How International Bankers Gained Control of America (video, 1998), https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1954955/, accessed January 17, 2019.

8 Ibid.

9 Hitchcock, “The History of the House of Rothschild.”

10 Ibid.

11 Bray Hammond, “Jackson’s Fight with the Money People,” American Heritage 7, no. 4, June 1956.

12 Andrew Jackson, quoted in Dean Henderson, “The Federal Reserve Cartel: Freemasons and the House of Rothschild,” Global Research, June 8, 2011, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-federal-reserve-cartel-freemasons-and-the-house-of-rothschild/25179, accessed January 17, 2019.

13 Hitchcock, “The History of the House of Rothschild.”

14 Cecil John Rhodes, “Confession of Faith,” June 2, 1877, http://pages.uoregon.edu/kimball/Rhodes-Confession.htm, accessed January 17, 2019.

15 Megan French, “Boer War Soldiers’ Records Published Online,” Guardian, June 24, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/jun/24/boer-war-soldiers-records-online, accessed January 17, 2019.

16 Owen Coetzer, Fire in the Sky: The Destruction of the Orange Free State (Johannesburg: Covos Day, 2000), pp. 82–83.

17 Philip Ziegler, Legacy: Cecil Rhodes, The Rhodes Trust, and Rhodes Scholarships (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 12.