Despite his immense loot, Rockefeller lived in fear of poverty. And he instilled this fear in his offspring in such intense degree that his fear of poverty has become a fixed, paranoid characteristic of the Dynasty. Rockefeller yearned, above all things, for “security” for himself in his piracy. This meant to him that he must loot and despoil everyone, enslave the world and rob everyone else of their possessions and security in order to make sure that no one more ruthless and criminal than himself could arise and rob him of his loot. Like an ugly and monstrous spider, John D. sat in the midst of a vast sea of conspiracy in which he had entrapped the U.S.A. and the rest of the world, ready to pounce on and devour his victims, mankind.

STUDENTS ARE TAUGHT IN SCHOOLS and universities throughout the United States that the cause of World War I was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, by a Serbian nationalist on June 28, 1914. The murder, according to this scenario, prompted conflict between Russia, Serbia’s ally, and Germany, the Austro-Hungarian protector. This conflict caused the various European countries to fall like dominoes into the abyss of war since they were bound by a network of alliances.

But World War I, like all wars, was caused by economic interests, and plans for the global conflict were underway decades before the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand. The creation of the German empire under Bismarck had upset the “balance of powers” that existed in Europe for more than two centuries. England ruled supreme over the continent until 1871. This supremacy had been repeatedly challenged by Spain and by France, but England always remained victorious. Because Germany grew increasingly stronger by acquiring colonies in Africa and by building up its military force, it became a severe threat to the economic hegemony of England. The threat was intensified when the German government obtained a concession from Sultan Abdul Hamid to drill the Baghdad-Mosul oilfields and to build a Baghdad-to-Berlin railroad in 1904.1

World War I, like all wars, was caused by economic interests, and plans for the global conflict were underway decades before the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand.

The British government, by this time, was keenly aware that whoever controlled the oil controlled the future. As early as 1882, Admiral Lord Fischer stressed the importance of oil as the fuel for the Royal Navy by saying: “The use of oil adds 50 percent to the value of any fleet that uses it. The use of oil would increase the strength of the British Navy by 33 percent, because it can refuel at any enemy’s harbor. Coal necessitates about one-third of the fleet being absent at the refueling of a base.”2

At that time, the international bankers, who were excluded from the economic development in Germany, sought for ways to limit and control Germany. Between 1894 and 1907, a number of international treaties were signed to have Russia, France, England, and other nations unite against Germany in the case of war. It was the task of the so-called Committee of 300 at the British Pilgrim Society to set the stage for World War. Members of the committee included Lord Albert Grey, Lord Arnold Toynbee, Lord Alfred Milner, and H. J. Mackinder, who became known as the father of geopolitics.3 Edward Bernays, the so-called father of public relations, and Walter Lippmann, the founding editor of the New Republic, were the American “specialists” of the Committee. Lord Rothermere, aka Harold Harmsworth, used his newspaper the Daily Mail as a tool to try out their “social conditioning” techniques on his readers. After a test period of six months, they had found that 87 percent of the public had formed opinions without rational or critical thought processes. Thereupon the English working class became subjected to a constant onslaught of propaganda designed to convince them that they were obliged to send their sons by the millions to their deaths.4 The experiment verified that human beings can be conditioned as easily as rats.

A war on the grand scale of World War I could not have been mounted without the establishment of the Federal Reserve System. The Fed, by churning out a seemingly endless supply of cash, could provide loans to foreign governments for the production of arms and munitions, chemicals, aircraft, tanks, submarines, and battleships. To make sure that the war would occur, Chase Manhattan and other Rockefeller banks, now flush with cash, provided Kaiser Wilhelm II with over $300 million.5 By 1917, the British War Office had borrowed $2.5 billion from Chase Manhattan and other Wall Street banks.6 Americans, without realizing it, were paying the bill for the massive produce of money through a hidden tax called inflation.7

But a grave problem arose. By 1915, the Germans were emerging as victorious. They had nearly captured Paris, crushed Serbia and Romania, bled the French Army until it mutinied, and vanquished the mighty Russian army.8 Even if the Germans did not attain victory, the possibility existed that the war could result in a stalemate. Since tanks were not manufactured until 1916, the armies had to rely on the infantries alone to stage an advance. But such advances were easily repelled since both sides had dug trenches protected by machine guns, barbed war, mines, and other obstacles. By 1916, the trenches had stretched over 400 miles from the Swiss border to the North Sea.9

It was becoming imperative for the money cartel to drag the United States into the conflict. But America stood as an isolationist nation. This was in keeping with the advice of George Washington, who said in his Farewell Address: “The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop. Europe has a set of primary interests which to us have none; or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.”10

Similarly, Thomas Jefferson in his inaugural address pledged “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none.”11 This tradition of isolationism was fortified by the millions of immigrants who came to America to escape from oppression. During the 1800s, the United States spanned North America without departing from its stance of isolationism. It fought the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War without forming foreign alliances or fighting on European soil.12

The problem of enticing the American government to the European slaughter was further compounded by the fact that Rockefeller, Morgan, and other members of the cartel were making a fortune by supporting both sides in the struggle. In 1915, Thomas W. Lamont, a partner of Morgan and Company, delivered the following speech to the American Academy of Political and Social Science in Philadelphia:

We are turning from a debtor into a creditor…We are piling up prodigious export trade balance….Many of our manufacturers and merchants have been doing a wonderful business in articles relating to the war [WWI]. So heavy have been the war orders running into the hundreds of millions of dollars, that now their effect is beginning to spread to general business….

This question of trade and financial supremacy must be determined by several factors, a chief one of which is the duration of the war. If…the war should come to an end in the near future…we should probably find Germany, whose export trade is now almost wholly cut off, swinging back into keen competition very promptly.

[Another factor that] is dependent on the duration of the war, is as to whether we shall become lenders to foreign nations upon a really large scale…Shall we become lenders upon a really stupendous scale to these foreign governments?…If the war continues long enough to encourage us to take such a position, then inevitably we would become a creditor instead of a debtor nation, and such a development, sooner or later, would tend to bring about the dollar, instead of the pound sterling, as the international basis of exchange.13

The money began to flow in January 1915 when the House of Morgan signed a contract with the British Army Council and the Admiralty. At the advent of modern warfare, the first purchase, curiously, was for horses, and the amount tendered was $12 million. But that was but the first drop in the banker’s bucket. Total purchases from the Allies eventually climbed to an astronomical $3 billion. Morgan’s office at 23 Wall Street became mobbed by brokers and manufacturers seeking to cut a deal. Each month, Jack Morgan presided over purchases that equaled the gross national product of the entire world just one generation before.14

The problem of securing America’s involvement in the struggle was solved by Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill persuaded David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, and other leading members of the government to yield to the money cartel’s demand that the British concede their claims to the rich oil fields of Saudi Arabia, one of the Empire’s vassal countries, to the Rockefellers. In exchange for this concession, the Rockefellers and other cartel members would participate in staging events that would bring America’s doughboys to the killing fields of France.15

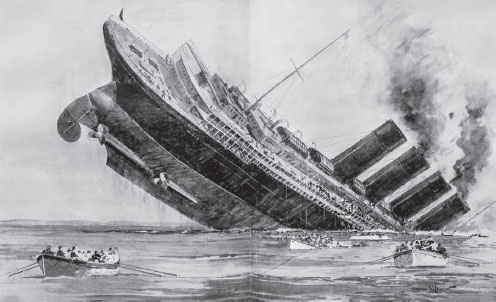

An incident had to be manufactured that would provoke the American people to abandon their stance of isolationism and to enter the fracas. It came with the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine on May 7, 1915. When the ship went down, 1,198 civilians, including 128 Americans, died, and the seemingly unprovoked act of aggression against a passenger ocean liner served to arouse anti-German sentiment throughout the country. Many of the 767 survivors popped up and down in the waves for three hours while seagulls swooped from the sky to peck out the eyes of the floating corpses.16 Few Americans realized that the sinking and delayed rescue had been planned by Winston Churchill and that members of the British Admiralty were acting in tandem with Britain’s Board of Trade, including Colonel Edward M. House of the Wilson Administration and American industrialists, along with J. P. Morgan, who had provided massive loans to Great Britain and the Allied forces.

The American public was not informed that the Lusitania was transporting six million rounds of ammunition and other military munitions to Britain. Upon the order of President Wilson, the ship’s original manifest was hidden away in the archives of the Treasury Department.17 Nor were they made aware that Churchill and other members of the Admiralty had directed the Lusitania to proceed at considerably reduced speed and without escort to the precise location within the Irish Sea where the German U-boat was lying in wait.18 And the public, for the most part, remained oblivious that the Germans had placed large ads in the New York newspapers to dissuade Americans from boarding the ocean liner.19

Few Americans realized that the sinking and delayed rescue [of the Lusitania] had been planned by Winston Churchill and that members of the British Admiralty were acting in tandem with Britain’s Board of Trade.

After the sinking of the Lusitania, stories about German atrocities began to capture headlines in U.S. newspapers, including the New York Times. One story reported that German soldiers were deliberately mutilating Belgian babies by cutting off their hands and, in some cases, even eating them. Another atrocity story involved a Canadian soldier who had supposedly been crucified with bayonets by the Germans. Many Canadians claimed to have witnessed the event, yet they all provided different versions of how it had happened. The Canadian high command investigated the matter, concluding that it was untrue. Other reports circulated of Belgian women, often nuns, who had their breasts cut off by the Germans. A story appeared in the Times about German corpse factories where bodies of British and French soldiers were supposedly turned into glycerin for weapons or food for hogs. The stories produced moral outrage throughout America and a hatred for the bloodthirsty “Hun.”

After the sinking of the Lusitania, stories about German atrocities began to capture headlines in U.S. newspapers, including the New York Times…. Few realized that the news came from the British Pilgrim Society and was circulated by the Morgans and the Rockefellers, who had gained control of America’s newspapers.

Few realized that the news came from the British Pilgrim Society and was circulated by the Morgans and the Rockefellers, who had gained control of America’s newspapers. On February 9, 1917, Congressman Oscar Callaway inserted this statement within the Congressional Record about Morgan’s ability to control and manipulate the national news:

In March, 1915, the J. P. Morgan interests, the steel, ship building and powder interests and their subsidiary organizations, got together 12 men high up in the newspaper world and employed them to select the most influential newspapers in the United States and sufficient number of them to control generally the policy of the daily press in the United States.

These 12 men worked the problems out by selecting 179 newspapers, and then began, by an elimination process, to retain only those necessary for the purpose of controlling the general policy of the daily press throughout the country. They found it was only necessary to purchase the control of 25 of the greatest papers. The 25 papers were agreed upon; emissaries were sent to purchase the policy, national and international, of these papers; an agreement was reached; the policy of the papers was bought, to be paid for by the month; an editor was furnished for each paper to properly supervise and edit information regarding the questions of preparedness, militarism, financial policies and other things of national and international nature considered vital to the interests of the purchasers.

This contract is in existence at the present time, and it accounts for the news columns of the daily press of the country being filled with all sorts of preparedness arguments and misrepresentations as to the present condition of the United States Army and Navy, and the possibility and probability of the United States being attacked by foreign foes.

This policy also included the suppression of everything in opposition to the wishes of the interests served. The effectiveness of this scheme has been conclusively demonstrated by the character of the stuff carried in the daily press throughout the country since March, 1915. They have resorted to anything necessary to commercialize public sentiment and sandbag the National Congress into making extravagant and wasteful appropriations for the Army and Navy under false pretense that it was necessary. Their stock argument is that it is “patriotism.” They are playing on every prejudice and passion of the American people.20

On April 6, 1917, the joint sessions of Congress approved President Wilson’s request for a declaration of war against the German Empire. U.S. intervention in the conflict was justified by Wilson’s belief that the war would make the world “safe for democracy.” Six senators voted against the declaration, including Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, and fifty members of the House of Representatives opposed it, including Jeannette Rankin of Montana, America’s first congresswoman.21

Despite government appeals for a million volunteers, only 63 thousand enlisted in the first six weeks, forcing Congress to institute compulsory military inscription. Under the 1917 Espionage Act, hundreds of Americans who opposed the draft were tossed into prison, including political activist Eugene Debs, who said: “Let the capitalists do their own fighting and furnish their own corpses and there will never be another war on the face of the earth.”22

The war gave rise to modern warfare. Huge plants sprouted up throughout the United States to produce military aircrafts, submarines, battleships, aircraft carriers, tanks, portable machine guns, flamethrowers, and automatic rifles. Military spending rose until it constituted 22 percent of the GNP in 1918. The principal beneficiaries were U.S. Steel, Bethlehem Steel, DuPont Chemical, Kennecott, and General Electric—all of which were related to the money cartel.23 Enterprising defense companies set up shop, including General Dynamics, which produced submarines, and Boeing, which produced aircraft. The military-industrial complex had come into existence.

By the summer of 1914, the British Navy was fully committed to oil, and the British government had assumed the role of majority stockholder in the Anglo Persian Oil Company, now known as British Petroleum (BP).24 But 80 percent of the oil that was used to fuel the Royal Navy and Army came from America, and 90 percent of the oil in America was owned by the Rockefellers.25

On November 11, 1918, the long war came to an end. Of the two million Americans who took part in the struggle, 116,000 were killed and 204,000 wounded. The European losses were staggering. Eight million soldiers and 6 to 10 million civilians were dead. The civilian casualties were caused by disease and starvation. No country suffered more than Russia with 1.7 million dead and five million wounded.26

On November 11, 1918, the long war came to an end. Of the two million Americans who took part in the struggle, 116,000 were killed and 204,000 were wounded. The European losses were staggering. Eight million soldiers and six to 10 million civilians were dead. The civilian casualties were caused by disease and starvation. No country suffered more than Russia with 1.7 million dead and five million wounded.

The survivors found themselves in a strange new world. Britain and France had been severely weakened and no longer represented a threat to the rising American political and economic hegemony. The German Empire had collapsed into financial shambles. The Austro-Hungarian Empire vanished, necessitating the restructuring of Eastern Europe. The Ottoman Empire, which had stood for six hundred years, no longer ruled over the Middle East and Central Asia. And the reign of the czars in Russia had been overthrown by Bolshevik revolutionaries, who pledged to inaugurate a world revolution.27

By the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on July 28, 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Germany lost one-tenth of her population and one-eighth of her territory. Germany’s overseas empire, the third largest in the world, was torn apart and handed over to the victors. German citizens, who lived in these German colonies, were obliged to forfeit all of their personal property. Japan was given the German concession in Shantung and the German islands north of the Equator. The German islands south of the Equator were handed over to Australia and New Zealand. Germany’s African colonies were shelled out to Britain, South Africa, and France. German waterways were now internationalized, and she was compelled to open her markets to Allied imports but denied access to Allied markets.28 Germany was also required to cede to the Allies the city of Danzig and its hinterlands, including the delta of the Vistula River on the Baltic Sea.29 This last stipulation would spark World War II, since the Germans, residing in Danzig, would call on Adolf Hitler to liberate them from the clutches of the League of Nations.

By the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed on July 28, 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Germany lost one-tenth of her population and one-eighth of her territory. “Treaty of Versailles Newspaper Article” by Kallen2021 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

But the loss of empire was only a part of the punishment. Germany was forbidden to build armored cars and tanks, to produce heavy artillery, and to maintain an air force. Her High Seas Fleet and merchant ships were confiscated as booty. And the German army was restricted to a force of 100,000 men.30 And then there was the matter of finances. Germany was required not only to pay the pensions of the Allied soldiers but also to cough up 32 billion gold marks—an amount equivalent to the entire wealth of the country—in reparations.31 This indemnity would be used to repay the international bankers for the loans with interest that they had provided to Great Britain and France.32

By 1923, the reparation payments imposed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles had caused the Weimar Republic to print such an outrageous quantity of paper money that 100 million marks was not sufficient to buy a box of matches.33 The hyperinflation was accompanied by an unemployment rate that soared to 33 percent. When Germany was no longer able to come up with the mandated annual payments of 132 billion gold marks to the Allies, French and Belgium forces took possession of the Ruhr Valley. As a result of the occupation, German miners in this area reduced coal production. This situation intensified the financial crisis and poised the possibility of a renewed outbreak of armed conflict.34

Within these dire developments, the Rockefellers spotted an opportunity to increase its wealth and came up with the Dawes Plan. As implemented in 1924, this plan called for the provision of $1.5 billion in loans from Morgan and Rockefeller to spark the German economy and to stabilize the German currency.35 Germany, at that time, represented carrion for the money vultures. The opportunities seemed limitless. Major German businesses could be bought for pennies on the dollar. The Daimler-Benz motor company, for example, could be had for the price of 227 of its cars.36 Some of the money was used to build theaters, sports stadiums, and even opera houses. But the lion’s share went for industrialization.37

The Dawes Plan was foolproof. It stipulated that the American bankers would be repaid with interest ahead of the reparation payments to France and Great Britain. And it met with immediate success. Businesses began to flourish, imports ballooned, and the austerity measures that had been imposed upon the German people were lifted. By 1926, the German government was back to running modest deficits of $200 million without inflation.38

A major beneficiary of the Plan was IG Farben, who received a $30 million loan from Rockefellers’ National City Bank. This funding allowed Farben to grow into the largest chemical company in the world. It produced 100 percent of Germany’s synthetic oil; 100 percent of its lubricating oil, and 84 percent of its explosives. German bankers on the Farben Aufsichsrat (the supervisory Board of Directors) included the Hamburg banker Max Warburg, whose brother Paul Warburg was a founder of the Federal Reserve System in the United States. Not coincidentally, in 1928, Paul Warburg became a director of American I. G., Farben’s wholly owned U.S. subsidiary, whose holdings came to include the Bayer Company, General Aniline Works, Agfa Ansco, and Winthrop Chemical Company.39 By 1933, Farben had become so wealthy that it could fund the Nazi Party’s rise to power. The ties to Hitler greatly increased the chemical company’s worth. By 1943, it was the leading producer of Zylon B gas, which was used in the concentration camps.40

1 Emanuel M. Josephson, The “Federal” Reserve Conspiracy and the Rockefellers: Their “Gold Corner” (New York: Chedney Press, 1968), p. 74.

2 Admiral Fischer, quoted in Emanuel M. Josephson, Rockefeller “Internationalist:” The Man Who Misrules the World (New York: Chedney Press, 1952), p. 187.

3 Jan Van Helsing, “Geheimgesellschaften und Ihre Macht in 20 Jahrhundert,” n. d., http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/sociopolitica/secretsoc_20century/secretsoc_20century.htm#Contents, accessed January 17, 2019.

4 Jan van Helsing, “Secret Societies and Their Power in the 20th Century,” 1998, http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/sociopolitica/secretsoc_20century/secretsoc_20century05.htm, accessed January 17, 2019.

5 Josephson, The “Federal” Reserve Conspiracy and the Rockefellers, p. 74.

6 Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick, The Concise Untold History of the United States (New York: Gallery Books, 2014), p. 14.

7 G. Edward Griffin, The Creature from Jekyll Island (New York: American Media, 2008), p. 260.

8 Michael Peck, “How Germany Could Have Won World War I,” National Interest, May 8, 2014, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/how-germany-could-have-won-world-war-i-10398, accessed January 17, 2019.

9 Mark John McCulloch, “How Long Were the World War I Trenches?” Quora, March 23, 2018, https://www.quora.com/How-long-were-World-War-1-trenches, accessed January 17, 2019.

10 George Washington, “Farewell Address,” 1796, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/washing.asp, accessed January 17, 2019.

11 James Simon, “Isolationism,” U.S. History, n. d., http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1601.html, accessed January 17, 2019.

12 Ibid.

13 Thomas W. Lamont, quoted in F. William Engdahl, Gods of Money: Wall Street and the Death of the American Century (San Diego: Progressive Press, 2011), p. 67.

14 Ibid.

15 Josephson, The “Federal” Reserve Conspiracy and the Rockefellers, p. 75.

16 Erik Larson, Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania (New York: Crown, 2015), p. 296.

17 Sam Greenhill, “Secret of the Lusitania: Arms Find Challenges Allied Claims It Was Solely a Passenger Ship,” Daily Mail, December 19, 2008, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1098904/Secret-Lusitania-Arms-challenges-Allied-claims-solely-passenger-ship.html, accessed January 17, 2019.

18 Gary Allen with Larry Abraham, None Dare Call It Conspiracy (San Diego: Dauphin Publications, 2013), p. 38.

19 Ibid.

20 Congressional Record, February 9, 1917, p. 2947.

21 Stone and Kuznick, The Concise Untold History of the United States, p. 15.

22 Eugene Debs, quoted in ibid., p. 17.

23 Dean Henderson, “The Federal Reserve Cartel: The Eight Families,” Global Research, June 1, 2011, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-federal-reserve-cartel-the-eight-families/25080, accessed January 17, 2019.

24 Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (New York: Free Press, 2008), pp. 138–40.

25 Daniel Yergin, “The Blood of Victory: World War I,” Modern History, n.d., http://erenow.com/modern/theepicquestforoilmoneyandpower/10.html, accessed January 17, 2019.

26 Stone and Kuznick, The Concise Untold History of the United States, p. 18.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid., p. 74.

29 Treaty of Versailles, Article 110, Section XI of Part III, June 28, 1919, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000002-0043.pdf, accessed January 17, 2019.

30 Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War, p. 72.

31 Stephen Mitford Goodson, A History of Central Banking and the Enslavement of Mankind (London: Black House, 2014), p. 91.

32 Ibid.

33 James Perloff, The Shadows of Power: The Council on Foreign Relations and the American Decline (Appleton, WI: Western Islands, 2005), p. 46.

34 Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey, and Steve Thompson, “The Ruhr Occupation,” Alpha History, 2014, http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/ruhr-occupation/, accessed January 17, 2019.

35 Perloff, The Shadows of Power, p. 46.

36 Liaquat Ahamed, Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World (New York: Penguin, 2009), p. 283.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Antony Sutton, “The Empire of I. G. Farben,” Reformation.org, 2004, http://www.reformation.org/wall-st-ch2.html, accessed January 17, 2019.

40 Perloff, The Shadows of Power, p. 47.