GARDENING was regarded as a respectable profession, with good opportunities for advancement for a hard-working young man intent on self-improvement. Apprenticeships enabled the passing-on of practical skills from experienced gardeners, and books and manuals facilitated private study. A would-be gardener had to take charge of his own career, securing funding for his apprentice fee, identifying the best gardens in which to learn his trade, being willing to travel around the country to gain experience, and making contact with influential gardeners who might provide a step up the ladder of advancement. After a hard day at work, the ambitious young gardener’s labours were not over: he might spend the evening studying books on botany, geometry and plant physiology, or attending lectures on natural history.

A gardener working on a private estate was entering a profession with a hierarchy just as stringent as that found in domestic service. The head gardener was in charge of the gardeners in the same way that the butler directed the indoor staff, each commanding the respect and obedience of his workforce. At the bottom of the career ladder was the garden boy, who, at around twelve years of age and with a decent education, was expected to undertake the most menial of garden tasks, such as washing pots, picking slugs from plants and scaring birds. After around a year of service, the garden boy would be taught how to prick out seedlings and tie in wall plants, and would be engaged in repetitive tasks such as these, gaining basic skills around the garden and practising horticultural techniques.

At sixteen years of age, a boy could progress to become an under-gardener, getting a good grounding in all departments of the garden and learning technical skills from his superiors. At this point, an ambitious young gardener might apply for a position in a different garden to gain a broad range of skills and experience before moving on to become a journeyman gardener.

Journeymen had a peripatetic working life, moving from garden to garden to develop skills in all areas of horticulture. Advancement was self-motivated and it was up to the individual to identify suitable gardens in which to seek employment. A renowned head gardener could offer high-quality training and bestow recommendations for advancement, but he would be looking for only the most ambitious and talented young gardeners to work under him. A journeyman might also seek work in a nursery establishment to learn propagation skills and to become familiar with the cultivation of newly introduced plants, and working in different parts of the country would provide experience of various growing conditions and the merits of different types of soil and climate.

The most menial and unskilled of garden jobs were given to the garden boy, often necessitating antisocial working hours. This illustration from 1887 shows a boy removing slugs at night by lamplight.

Journeymen would learn from experienced gardeners but would also be expected to undertake considerable study from books and manuals in the evening, supplementing their horticultural knowledge with the study of book-keeping, foreign languages, technical drawing, natural history and chemistry. Once all the necessary skills had been learned, a gardener could apply for a position as a foreman, leading one of the departments of the garden, and adding management of staff to his repertoire of skills. Depending on the size and complexity of the garden, a foreman might progress to become a general foreman or deputy head gardener before being ready to apply for a position as head gardener.

Through apprenticeships, young gardeners could learn horticultural skills from experienced gardeners. The quality of their training depended on the knowledge and benevolence of the gardener they were apprenticed to. This garden boy is pictured in c. 1910.

The head gardener of a large garden had to show talents beyond his horticultural skills. He would be expected to manage a large team of gardeners and oversee the work of all the garden departments, ensuring that seasonal tasks were done at appropriate times and that all work met the exacting standards required. He had to satisfy the requirements of the owner of the garden, often liaising with the lady of the house on colour schemes and planting plans, and was subject to the family’s whims and impulses. He was responsible for a large budget and would have to keep tight control of spending on wages and garden sundries, keeping his accounts in order for regular inspection by his employer’s accountant or estate manager.

The head gardener was also required to be a man of taste, with a certain level of artistic ability. The layout of a garden was often conceived by an architect or designer brought in by the garden owner, but the head gardener could also be called upon to create a garden to realise the ideas of his employer. Some head gardeners were given more artistic freedom than others, depending on the nature of their employer. A garden owner with an interest in botany might encourage the introduction of new plants from abroad into the garden, creating an arboretum or an alpine collection, and allowing the head gardener to show off his horticultural skills. The annual display of summer bedding provided the ideal opportunity for a head gardener to showcase his artistic talents as each year a new colour scheme or pattern could be devised.

A nineteenth-century bedding plan from Stagenhoe in Hertfordshire indicates the level of artistry required by a head gardener when designing annual bedding displays.

A head gardener of a smaller establishment might be working single-handed, or with one or two gardeners with whom to share the workload. In the newly created suburbs, the professional classes were making gardens and employing head gardeners to manage them, but they might also take an active interest in horticulture themselves, thus limiting the responsibilities of the head gardener. At a large and renowned establishment, the head gardener would not expect to carry out any practical work himself. He would know exactly what was happening in the garden through regular inspections and by overseeing the work of his foremen, and he might engage in specialised technical work such as hybridisation or propagating orchids or ferns, depending on his particular interests.

Three young apprentices are pictured alongside the experienced gardeners from whom they will learn their trade.

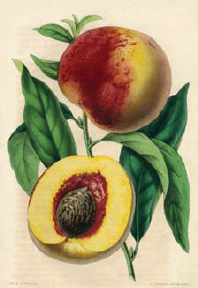

A large kitchen garden would have a range of glasshouses, divided into sections for the cultivation of different fruits. An illustration of a peach house from 1879 shows how the fruit could be trained up frames to maximise yield.

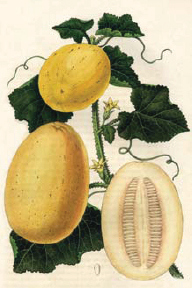

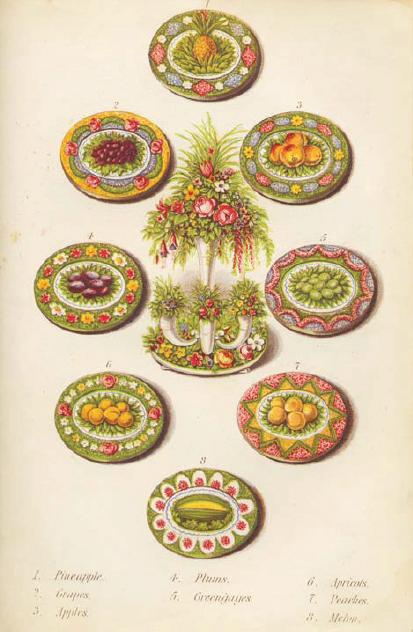

A large garden was divided into various departments, each with its own foreman in charge, and a trainee gardener would have to work in each department to gain experience in different forms of garden craft. The formal gardens and shrubberies had to be maintained in perfect condition for garden walks and views from the windows of the house, with bedding planted and lawns mown. The kitchen garden provided all the produce needed for the family, both while at home and also when staying at their other residences, where it was transported to arrive in peak condition for presentation at table. Gardeners working in the kitchen garden would be responsible for growing fruit and vegetables for consumption all year round, and so, as well as the walled garden where hardy fruit would be trained up the walls and vegetables cultivated in neatly sectioned beds, much was grown in glasshouses. There were ranges for peaches, grapes, melons and cucumbers and a specialised pit for pineapples.

There was a hierarchy in place between departments, with some requiring more horticultural expertise or practical skill than others. A foreman in the kitchen garden might seek career advancement to become foreman of the flower garden, and then progress to working in the conservatory, with the forcing department deemed the most prestigious in terms of skill and status. The forcing of fruit and vegetables to provide out-of-season delicacies was considered an essential part of life in the Victorian country house and was a topic of much one-upmanship between both gardeners and owners. To serve an out-of-season strawberry or a home-grown pineapple, or to decorate the table at Christmas with a bouquet of flowers from the glasshouse, was a display of wealth and prestige, demonstrating not only the skill of the head gardener, but also the superiority of his employer.

The new species of orchids being introduced from abroad prompted a mania of collecting with their exotic forms and colours, shown in an illustration from Belgique Horticole from 1851–4.

Grapes were raised in a vine house, the fruit being forced to provide an out-of-season delicacy.

Peaches were a favourite Victorian glasshouse fruit, ideal for displaying on the dining table.

Melons were grown in glasshouses using special net bags to support their weight on the vine.

Floral decorations for the dining table were at their most elaborate from the 1870s to the end of the nineteenth century. Multi-tiered flower stands, like the one shown here, were used by head gardeners, who were responsible for arranging the flowers as well as growing them.

Florist’s flowers were also grown in the garden to provide cut flowers for the house, and their cultivation was a further specialist garden department. Flowers were grown either in a cutting garden – or ‘reserve garden’ – or in borders flanking the central path through the kitchen garden, providing a decorative screen to the rows of vegetables. When the family were spending the season at their London home, cut flowers were transported daily from their country estate, arriving on the overnight train. After cutting the flowers, gardeners would carefully wrap them in spinach leaves for protection and then pack them in cases filled with sphagnum moss. Each bunch would be labelled with instructions for the house staff detailing which vase to use and which room the arrangement was intended for.

The head gardener would be obliged to keep up with the latest fashions in floral arrangements and acquire the necessary skills to master the delicate art of floristry. The ladies of the house generally arranged the flowers for the bedrooms, but the head gardener was responsible for the main reception rooms. In the winter months, when cut flowers from the garden were scarce, foliage plants and exotics from the glasshouse were brought into the house and arranged in pots, being swiftly replaced with a pristine specimen the moment they were past their prime. For special occasions, the head gardener would not only have to create splendid floral arrangements to decorate the reception rooms and dining table, but would also be expected to supply fresh flowers to adorn the dresses and hair of the ladies, always fulfilling their exacting requirements as to colour, size and fragrance.

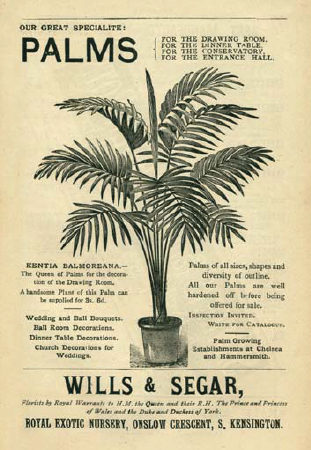

Foliage plants, such as the palms in this advertisement from 1895, were popular in Victorian drawing rooms. The head gardener had to keep a close eye on houseplants and replace them before they passed their prime.

The demand for elaborate floral decorations in the late nineteenth century was such that floristry became a specialist branch of the gardening profession. Books and articles were published on the subject, and specialised floristry products and flower stands were marketed. Some talented gardeners set up in business offering their services in floral design, and others with an aptitude for propagation established nursery businesses to supply the growing demand for plants.

By the mid-nineteenth century floral art had become a specialism of the gardening trade, with businesses established to meet the increasing demand for floral decorations.

Publications such as The Floricultural Cabinet and Florist’s Magazine, shown here in an edition from 1840, enabled gardeners to keep up with fashions in floral decoration.

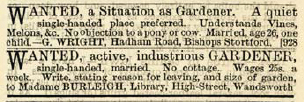

Gardeners on private estates were often appointed by recommendation from their previous employer, so ambitious gardeners were keen to make a good impression and to work under head gardeners who commanded some influence in the profession. By the 1860s, advertisements began to appear in the horticultural press, both from garden owners with situations vacant and from gardeners advertising their services to potential employers. Gardening magazines and journals proliferated in the mid-nineteenth century and were read by both garden owners and professional gardeners, thus providing an ideal forum for recruitment.

A cutting from Gardeners Illustrated shows two advertisements placed in 1884: one by a gardener seeking work, the other by an employer in search of a gardener.

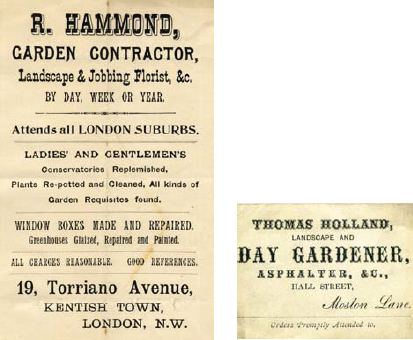

Not all gardeners were employed in private service: some worked in nurseries, and others grew fruit and vegetables in market gardens. Those who could not afford the necessary training, or were unwilling or unable to travel to other parts of the country to find employment, advertised their services as jobbing gardeners, taking work where they could find it. Such work was often poorly paid and seasonal, offering little opportunity for advancement. Women were often employed as casual labourers doing weeding and other menial work, and seasonal garden jobs such as grass-cutting were done by hired labourers. Before the invention of the lawnmower, grass was cut by teams of labourers using scythes. This task was done in the early morning when the grass was still wet with dew. Because of the antisocial hours, the low pay and the physically demanding and repetitive nature of the work, such labourers commanded little respect and were barely regarded as gardeners at all.

Men and women with varying levels of horticultural skills were employed in market gardens, established in or near towns and cities to provide a plentiful supply of fruit and vegetables for market.

Jobbing gardeners had to find enough work to support themselves financially, advertising their services locally and distributing trade cards.

A wage bill from 1863 details payments to a team of labourers for barrowing manure. The lowest paid was given just a shilling a day, and five of the six labourers were women.