A SUCCESSFUL head gardener needed business acumen as well as horticultural talent. To ensure the smooth running of each department within the garden required an aptitude for staff management, with trusted foremen appointed to oversee the work of the junior gardeners. The garden finances had to be kept in good order, with sources of revenue, such as the sale of surplus garden produce, capitalised upon to balance the account books. The head gardener was responsible for the pleasure grounds, formal gardens, kitchen garden, cut flower garden, glasshouses, and floral decorations in the house, all of which had to be perfectly presented in all seasons. He had to predict and respond to the weather, ensure the health and vitality of the plants in his care and meet the exacting requirements of his employer.

While many tasks in the garden were routine and seasonal, carried out according to the weather and the calendar, some were more complex and required meticulous planning and organisation. The Victorian fashion for summer bedding required lengthy behind-the-scenes preparation to produce the stunning effects demanded by owners keen to make an impression. The design of the bedding was planned, often in consultation with the lady of the house for her guidance on colour scheme and layout, and the beds would be measured up, careful calculations being made to determine the number of plants required of each colour and species. The head gardener would then have to order the seeds and ensure there were adequate supplies of pots and compost available, as well as allocating space in the glasshouses for raising the seedlings. Depending on the size and complexity of the scheme, between ten thousand and fifty thousand plants might be required, and an experienced head gardener would put in place contingency plans to allow for unforeseen complications, such as pest infestations, boiler failure and dangerous late frosts. The whole operation required large amounts of labour at each stage, from the initial pot washing, barrowing of compost and seed sowing, to watering, pricking out, potting on, hardening off, and finally moving plants into position and planting out in the garden.

Matthew Balls (1817–1905) was head gardener at Stagenhoe in Hertfordshire.

Donald Beaton (1802–63) was well-known for his experiments in bedding design and contributed to the popularity of bedding as a fashionable feature of Victorian gardens. Beaton began his career in his native Scotland, working on a private estate near Forres before joining a nursery in Perth, and then working in the gardens of the Caledonian Horticultural Society in Edinburgh. He travelled south and was employed in private gardens, and in the 1830s began working at Shrubland Park in Suffolk, where he developed his bedding schemes. Dismissing new ideas on complementary colour theory, he advocated the shading of similar colours, planted to blend into one another to produce a sophisticated result that took into account a gardener’s empirical knowledge of the effects of light and shadow, of daylight in differing atmospheric conditions, and of the influence of green leaves between the coloured flowers. His ideas were publicised through articles in The Gardener’s Magazine and a weekly column in The Cottage Gardener, and his theories were tested in his acclaimed designs at Shrubland Park.

This bedding plan, designed by Matthew Balls for the gardens at Stagenhoe, indicates the complexity of design and the number of different plants required to create a summer bedding display.

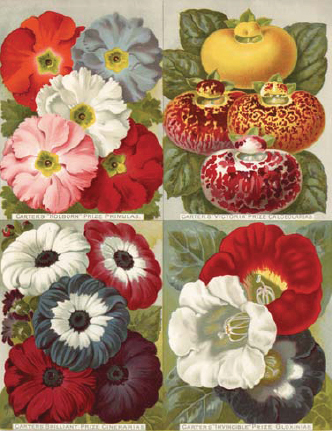

Annual bedding plants were bred by nurseries in a range of bright and contrasting colours, as depicted in an illustration from Carter’s seed catalogue of 1898.

As the debate over bedding continued in the pages of the horticultural press, Beaton’s colour innovations were spurred on by his friendly rivalry with fellow head gardener George Fleming (1809–76), working from 1841 at Trentham Park in Staffordshire, where he was famous for his long ribbon borders (see overleaf). A near namesake with innovative ideas on bedding design was John Fleming (1822/3-83), head gardener at Cliveden in Buckinghamshire from 1855. He trialled the use of spring bulbs in bedding displays and incorporated foliage plants as well as flowers in his designs. The culmination of his experimentation came in 1870 when The Gardener’s Chronicle published a report describing Fleming’s innovative design for a patterned bed of dwarf foliage plants and succulents incorporating his employer’s monogram. This smooth, flat, closely patterned style of planting, named ‘carpet bedding’, was imitated in gardens around the country, incorporating heraldic devices, pictures, patterns and mottoes, and provided an opportunity for head gardeners to take horticultural artistry to a new level.

If an owner or head gardener had a particular interest or enthusiasm, such as cultivating orchids or ferns, they could specialise in collecting or breeding specific plants and gain renown for garden and gardener. The many new species being introduced to the gardens of Britain by plant hunters returning from exotic and unexplored countries provided opportunities for novelty and one-upmanship. Planting an avenue of the newly introduced monkey puzzle tree, or being the first to nurture a new species of lily into flower, would propel a garden into the limelight, and a head gardener could enjoy an increase in his professional standing through such horticultural achievements.

Long bands of bedding plants in contrasting colours made up the ribbon borders at Trentham in Staffordshire, created by head gardener George Fleming.

John Gibson (1815–75) worked at Chatsworth under Joseph Paxton, who nominated him to travel to India on a plant-collecting expedition in 1836. He brought back forty-five cases of plants, among them over one hundred new species of orchid, and was rewarded for his success with a promotion to foreman of the exotic plant department. After seventeen years at Chatsworth, Gibson became the superintendent of Victoria Park in London; then, in 1854, he laid out a new park at Battersea. Using his knowledge of exotic plants, he experimented with subtropical bedding, creating the right growing conditions for striking foliage plants such as tree ferns and Dracaena. The effects were highly praised, and Gibson’s innovative plantings were emulated in other gardens and parks.

William Barron (1805–91), head gardener to the Earl of Harrington, became known for his part in the creation of an extraordinary garden at Elvaston Castle in Derbyshire, which he began in 1830. Barron had served his apprenticeship at Blackadder in the Scottish Borders before continuing his training at Edinburgh Botanic Garden, and was then employed in stocking the glasshouses at Syon Park in south-west London. He spent the next twenty years creating a garden at Elvaston inspired by historic tradition and influenced by his employer’s romantic tastes. The Earl’s reclusive nature ensured that his remarkable garden was hidden from public view until his death in 1851; it was then opened to the public and caused a sensation. In place of the fashionable terraces of massed bedding there was a series of formal gardens enclosed by hedges displaying architectural topiary, fountains and specimen trees, inspired by the exotic gardens of the Alhambra and eastern tradition. He also created a pinetum and an avenue with multiple rows of trees of different species. All of this was reported to great acclaim in The Gardener’s Chronicle in 1851 and prompted a renewed interest in topiary.

Head gardener at Cliveden, John Fleming’s innovative use of low-growing foliage plants to create patterns like those on a carpet led to a new craze in bedding, culminating in complex three-dimensional figures and mechanical floral clocks. This design for carpet bedding was published in the Gardener’s Assistant in 1888.

Barron continued to work at Elvaston until 1865, when he left to establish his own nursery and landscape gardening business in Derbyshire, where he was later joined by his son. His work at Elvaston had brought him renown in the transplantation of mature trees, for which he had developed a system allowing him to move large trees successfully over considerable distances, bringing an instant maturity to new gardens. In 1852 he published The British Winter Garden, which described the use of conifers to provide winter colour and explained his methods of transplantation. His innovative techniques and design flair, together with the publicity generated when the garden at Elvaston was opened, enabled Barron to develop his own successful business, trading on his horticultural reputation.

The extraordinary garden of Mon Plaisir at Elvaston in Derbyshire, created by head gardener William Barron, caused a sensation when it opened to the public in 1851. The garden is pictured in E. Adveno Brooke’s Gardens of England, 1856–7.

William Barron developed a machine that enabled mature trees to be transported over large distances and successfully transplanted. A photograph of George Jackman of Surrey shows the machine in action in c. 1914.

Head gardeners who were successful in the hybridisation of plants were able to enjoy the prestige that this brought in the horticultural profession while also enhancing the status of the garden in which they were employed. New cultivars of plants were sent to the Horticultural Society to be given the correct botanical nomenclature, which was often influenced by the name of the garden in which they were grown, of the owner or his wife, or sometimes of the head gardener who had raised the plant. This ensured the longevity of a gardener’s reputation by recording his name in the annals of horticultural history.

The work of James Comber (1866–1953) is honoured in the new varieties of Rhododendron, Camellia and Magnolia he raised as head gardener at Nymans in West Sussex. Comber began working for Ludwig Messel at Nymans in 1895 after completing his training in a typically peripatetic style, beginning as a garden boy at Wakehurst Place in West Sussex, then moving to nearby Dencombe after three years, then a few miles further away to Tilgate Park as a journeyman for a further three years. In 1888 he gained experience at the celebrated Veitch Nurseries, and then was recommended by the nursery to work at Ashby St Leger’s Lodge in Warwickshire, where he was soon promoted to foreman. He then worked at Drinkingstone Park in Suffolk, before being appointed foreman at Longfield Castle in Wiltshire. Shortly afterwards, he was recommended as head gardener at Bignor Park in West Sussex, and two years later he began working at Nymans, where he settled and spent the next fifty years building the reputation of the garden.

The new species of Rhododendron and Azalea being brought to Britain by plant-hunters were extensively hybridised to create new cultivars. At Nymans in West Sussex, head gardener James Comber raised several new varieties.

At Nymans, Comber found soil that was remarkably fertile and a rich employer who was enthusiastic about plants. Together they created a pinetum, a rock garden and a heath garden, stocked the newly built conservatory, cultivated many rare plants from abroad, and experimented with hybridisation. Comber was paid well at Nymans and was provided with a large cottage next to the kitchen garden, in which he and his new wife, Ethel, lived for the rest of their lives. His horticultural achievements are remembered in the red Rhododendron ‘James Comber’.

Head gardeners could also make a name for themselves by submitting articles for publication in one of the many horticultural magazines or by writing a book drawing on their experience or specialism. Having work published was a means to self-promotion and could gain horticultural renown as well as earning some money. Head gardeners could provide advice on cultivation techniques, recommend new products, review other gardens or instigate horticultural debate. Once a professional reputation had been achieved, founded on a combination of horticultural success and self-promotion, a head gardener might then be invited to become a judge at a flower show or to join the editorial board of a gardening journal. Apprentices would be keen to work under him, his advice would be sought by colleagues, and his employment prospects would be enhanced.

Rewards could also come in the form of certificates, medals and prize money. Horticultural shows were established up and down the country by local societies, and keen gardeners vied with one another to produce the best vegetables, fruit and flowers. The most prestigious shows were held in London, organised by the Royal Botanic Society at Regent’s Park and the Horticultural Society at Chiswick, later moving to Kensington. These shows gave head gardeners the opportunity to compete against the horticultural elite, matching themselves against the celebrated Veitch Nurseries or distinguished aristocratic gardeners, as well as measuring up to their most illustrious contemporaries. Although the prizes were awarded in the name of the garden owner, a head gardener would often reap rewards in terms of heightened professional status among his peers or the increased favour of his employer. Formal recognition of achievement was bestowed in awards such as the Veitch Memorial Medal, established in the 1870s to reward outstanding contributions to the science and practice of horticulture, and the Victoria Medal of Honour, first awarded by the Royal Horticultural Society in 1897 to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee.

The awarding of prizes at horticultural shows was a serious matter, and being invited to judge the exhibits signified the high professional status to which many head gardeners aspired. This photograph dates from c. 1905.

James Barnes (1806–77) built up a considerable reputation in the horticultural profession through his successful cultivation of many rare plants and his exacting standards, but his fame rested mainly on the cultivation of pineapples. It was acknowledged among gardeners in the nineteenth century that the pineapple was the most difficult plant to propagate and nurture to produce fruit in Britain, and any gardener able to achieve this was highly regarded in the profession. At the invitation of John Loudon, Barnes wrote a series of twenty-four articles for The Gardener’s Magazine, beginning in 1842, sharing his cultivation methods and horticultural expertise.

At horticultural shows gardeners could gain recognition among their peers for their achievements, although certificates were awarded in the name of the owner of the garden rather than the head gardener.

Barnes began his gardening career aged five, weeding and scaring birds with his father, who was a gardener, and he was officially apprenticed to him at the age of eight. By the time he was twelve, he had secured work in a London market garden, and over the next few years he worked in several market gardens in the capital, where he became a specialist in the cultivation and breeding of cucumbers. After working as a head gardener in Surrey, Essex and Kent, Barnes was appointed head gardener in 1839 to Lord Rolle at Bicton in Devon. After many successful years at Bicton, Barnes left in 1869 following a disagreement with his employer. He claimed he had been badly treated by Lady Rolle, who set out to tarnish his reputation when he became ill through overwork and was no longer able to carry out his duties. Barnes successfully sued his employer for libel and was awarded £200 in damages, emerging with his reputation intact and upholding the professional standing of gardeners.

The relationship between head gardener and employer was integral to the successful management of a garden. Joseph Paxton (1803–65) rose through the ranks of the gardening profession, using his talent, determination and ambition to achieve a knighthood, a seat in Parliament, considerable wealth and a distinguished reputation. This was all made possible through the horticultural affinity and mutual respect he shared with his employer, the Duke of Devonshire, at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire.

Paxton was of humble birth – his father was a farm labourer, who died in 1810 when Paxton was only six years old – and he followed his elder brother into gardening, working as a garden boy at Battlesden Park in Bedfordshire. He was then apprenticed to William Griffin, the head gardener at Woodhall in Hertfordshire, who encouraged the young Paxton in his horticultural career. After three years of training he returned to Battlesden and then, following the death of his mother in 1823, he decided to seek his fortune in London. He was soon appointed as a trainee gardener at the Chiswick garden of the Horticultural Society, where he was promoted after a year to under-gardener in the arboretum, cultivating the new species of trees arriving from abroad. In 1826, while working at Chiswick, Paxton met the Duke of Devonshire and made such a favourable impression that the Duke spontaneously invited him to become head gardener at Chatsworth, increasing his wages from 18s a week to £65 a year, with a cottage provided.

Paxton had evidently proved his worth to the Duke, as three years later he was given the additional responsibility of managing the woodland on the estate as well as the gardens, and his salary had increased to £226 a year. By 1849 Paxton’s role had expanded to that of agent for the entire estate at Chatsworth, controlling the accounts for the house, garden, woodland, farms, villages, schools and fisheries, amounting to around £26,000. His salary rose to £500 a year and he employed two assistants to help with the workload. Three years later he was earning £650 a year and the Duke rewarded him further by remodelling his cottage into a grand villa with a turret and large gardens. Paxton worked at Chatsworth until the Duke’s death in 1858.

James Barnes, head gardener at Bicton in Devon, was regarded as Britain’s premier pineapple grower, winning first prize for his pineapples at the prestigious RHS International Exhibition in 1866.

Much of the success of Paxton’s career was due to his relationship with the Duke. Paxton was a loyal servant who, despite the inequality of their social status, became a trusted friend of his aristocratic employer, travelling abroad with him, organising his affairs and sharing his horticultural vision. The Duke’s immense wealth and propensity for spending allowed Paxton to create a garden of ambitious splendour, with fountains soaring over 80 metres high, a huge glasshouse known as the Great Stove, filled with exotic specimens, an arboretum planted with rare trees, and a rock garden of magnificent proportions. A visit by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert was organised with great fanfare in 1843, and Paxton enthralled the royal guests with a spectacular firework display and lamp-lit tour of the Great Stove.

Paxton’s artistic and engineering feats in the garden were matched by his horticultural achievements. In 1836 Paxton caused a sensation when he exhibited Musa cavendishii at the Horticultural Society, the first banana plant to fruit in Britain, and then in 1849 he succeeded where others had failed by producing a flower from the magnificent giant waterlily, Victoria regia. Paxton’s talents extended to architecture and structural engineering, demonstrated by his design and construction of the Great Stove at Chatsworth, completed in 1840. This complex glazed building employed over five hundred workers, who constructed 40 miles of sash bars to enclose the sheet glass panes, and incorporated underground tunnels to facilitate deliveries of coal to the eight boilers, providing heat to the glasshouse through 7 miles of pipes.

The Great Stove at Chatsworth was designed by Paxton and completed in 1840 at a cost of over £36,000. The conservatory was filled with temperate and sub-tropical plants, the impressive display prompting Charles Darwin to declare that ‘Art beats nature altogether there’.

The success of the Great Stove prompted private commissions for glasshouses from some of the Duke’s friends, and Paxton was also the architect of several country houses, despite his lack of formal training. He designed Mentmore in Buckinghamshire, an eighty-room mansion completed in 1855 and complemented by an impressive garden, for Baron Meyer de Rothschild, and he worked on other projects for the Rothschilds in France. He also received commissions for public parks, beginning with Prince’s Park in Liverpool in 1841 and Birkenhead Park in 1843, before going on to design other parks and cemeteries around the country, while still fulfilling his demanding role at Chatsworth.

Paxton is best remembered for his design for the Crystal Palace, which housed the Great Exhibition of 1851. Building on his experience of glasshouse construction, he created a vast cast-iron and glass structure of grand proportions, which complemented the British industrial and artistic achievements displayed within. The exhibition attracted over six million visitors and, when it closed, the building was dismantled and moved to Sydenham, where Paxton designed an impressive garden around it for the enjoyment of the public. Joseph Paxton was now a household name, and he was rewarded for his endeavours by the Queen, who bestowed a knighthood on him at Windsor Castle in 1851. His reputation was further enhanced when he was appointed Justice of the Peace for Derbyshire in 1853 and then elected MP for Coventry in 1854, and he served on the boards of the railway companies in which he invested his increasing fortune. He was a fellow of the Linnaean Society, an honorary fellow and vice-president of the Horticultural Society, a member and vice-president of the Royal Society of Arts, and an associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers.

Alongside his political, architectural, managerial, social and familial duties, Paxton maintained his professional standing in horticulture and published articles on gardening and a monograph on dahlias. He also founded The Horticultural Register in 1831, The Magazine of Botany in 1834, and The Gardener’s Chronicle in 1841, all of which were affordable, accessible and aimed at the working gardener. Paxton had proved that through hard work, aptitude and tenacity, a labourer’s son could penetrate the upper echelons of society through a career in gardening.

Paxton’s Crystal Palace was moved to a new site in Sydenham when the Great Exhibition closed, and it became a popular venue for concerts, exhibitions and socialising, surrounded by spectacular gardens with water jets, carpet bedding and model dinosaurs.