The Performance Management Revolution

by Peter Cappelli and Anna Tavis

WHEN BRIAN JENSEN TOLD HIS AUDIENCE of HR executives that Colorcon wasn’t bothering with annual reviews anymore, they were appalled. This was in 2002, during his tenure as the drugmaker’s head of global human resources. In his presentation at the Wharton School, Jensen explained that Colorcon had found a more effective way of reinforcing desired behaviors and managing performance: Supervisors were giving people instant feedback, tying it to individuals’ own goals, and handing out small weekly bonuses to employees they saw doing good things.

Back then the idea of abandoning the traditional appraisal process—and all that followed from it—seemed heretical. But now, by some estimates, more than one-third of U.S. companies are doing just that. From Silicon Valley to New York, and in offices across the world, firms are replacing annual reviews with frequent, informal check-ins between managers and employees.

As you might expect, technology companies such as Adobe, Juniper Systems, Dell, Microsoft, and IBM have led the way. Yet they’ve been joined by a number of professional services firms (Deloitte, Accenture, PwC), early adopters in other industries (Gap, Lear, OppenheimerFunds), and even General Electric, the longtime role model for traditional appraisals.

Without question, rethinking performance management is at the top of many executive teams’ agendas, but what drove the change in this direction? Many factors. In a recent article for People + Strategy, a Deloitte manager referred to the review process as “an investment of 1.8 million hours across the firm that didn’t fit our business needs anymore.” One Washington Post business writer called it a “rite of corporate kabuki” that restricts creativity, generates mountains of paperwork, and serves no real purpose. Others have described annual reviews as a last-century practice and blamed them for a lack of collaboration and innovation. Employers are also finally acknowledging that both supervisors and subordinates despise the appraisal process—a perennial problem that feels more urgent now that the labor market is picking up and concerns about retention have returned.

But the biggest limitation of annual reviews—and, we have observed, the main reason more and more companies are dropping them—is this: With their heavy emphasis on financial rewards and punishments and their end-of-year structure, they hold people accountable for past behavior at the expense of improving current performance and grooming talent for the future, both of which are critical for organizations’ long-term survival. In contrast, regular conversations about performance and development change the focus to building the workforce your organization needs to be competitive both today and years from now. Business researcher Josh Bersin estimates that about 70% of multinational companies are moving toward this model, even if they haven’t arrived quite yet.

The tension between the traditional and newer approaches stems from a long-running dispute about managing people: Do you “get what you get” when you hire your employees? Should you focus mainly on motivating the strong ones with money and getting rid of the weak ones? Or are employees malleable? Can you change the way they perform through effective coaching and management and intrinsic rewards such as personal growth and a sense of progress on the job?

With traditional appraisals, the pendulum had swung too far toward the former, more transactional view of performance, which became hard to support in an era of low inflation and tiny merit-pay budgets. Those who still hold that view are railing against the recent emphasis on improvement and growth over accountability. But the new perspective is unlikely to be a flash in the pan because, as we will discuss, it is being driven by business needs, not imposed by HR.

First, though, let’s consider how we got to this point—and how companies are faring with new approaches.

How We Got Here

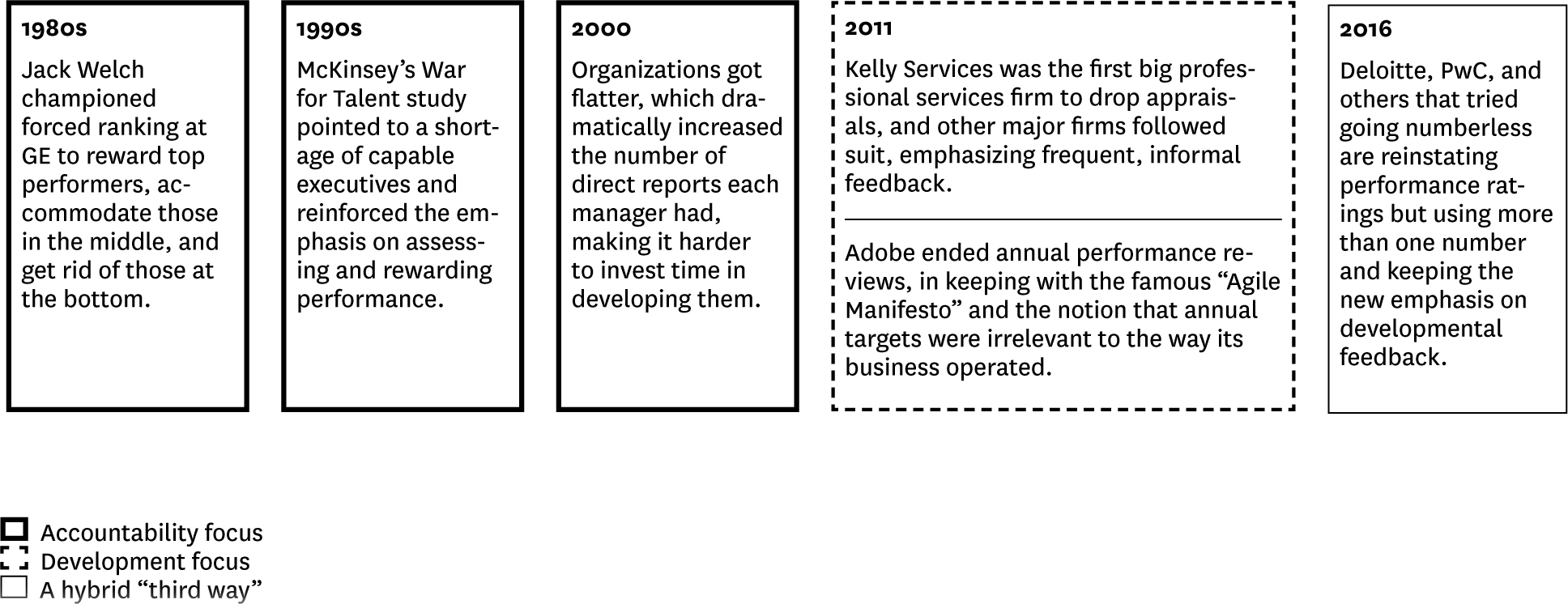

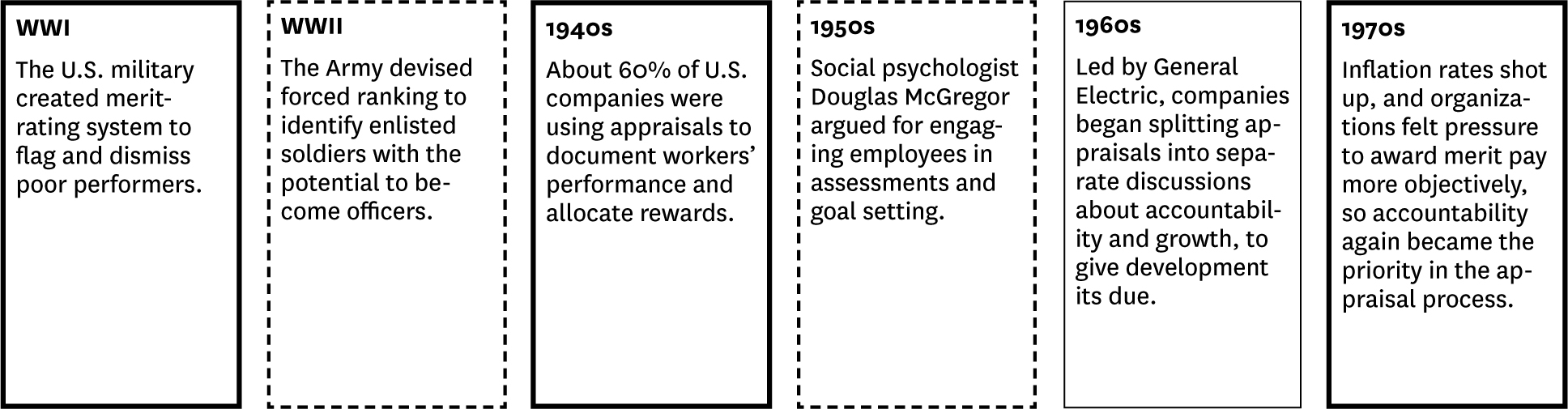

Historical and economic context has played a large role in the evolution of performance management over the decades. When human capital was plentiful, the focus was on which people to let go, which to keep, and which to reward—and for those purposes, traditional appraisals (with their emphasis on individual accountability) worked pretty well. But when talent was in shorter supply, as it is now, developing people became a greater concern—and organizations had to find new ways of meeting that need.

From accountability to development

Appraisals can be traced back to the U.S. military’s “merit rating” system, created during World War I to identify poor performers for discharge or transfer. After World War II, about 60% of U.S. companies were using them (by the 1960s, it was closer to 90%). Though seniority rules determined pay increases and promotions for unionized workers, strong merit scores meant good advancement prospects for managers. At least initially, improving performance was an afterthought.

And then a severe shortage of managerial talent caused a shift in organizational priorities: Companies began using appraisals to develop employees into supervisors, and especially managers into executives. In a famous 1957 HBR article, social psychologist Douglas McGregor argued that subordinates should, with feedback from the boss, help set their performance goals and assess themselves—a process that would build on their strengths and potential. This “Theory Y” approach to management—he coined the term later on—assumed that employees wanted to perform well and would do so if supported properly. (“Theory X” assumed you had to motivate people with material rewards and punishments.) McGregor noted one drawback to the approach he advocated: Doing it right would take managers several days per subordinate each year.

By the early 1960s, organizations had become so focused on developing future talent that many observers thought that tracking past performance had fallen by the wayside. Part of the problem was that supervisors were reluctant to distinguish good performers from bad. One study, for example, found that 98% of federal government employees received “satisfactory” ratings, while only 2% got either of the other two outcomes: “unsatisfactory” or “outstanding.” After running a well-publicized experiment in 1964, General Electric concluded it was best to split the appraisal process into separate discussions about accountability and development, given the conflicts between them. Other companies followed suit.

Back to accountability

In the 1970s, however, a shift began. Inflation rates shot up, and merit-based pay took center stage in the appraisal process. During that period, annual wage increases really mattered. Supervisors often had discretion to give raises of 20% or more to strong performers, to distinguish them from the sea of employees receiving basic cost-of-living raises, and getting no increase represented a substantial pay cut. With the stakes so high—and with antidiscrimination laws so recently on the books—the pressure was on to award pay more objectively. As a result, accountability became a higher priority than development for many organizations.

Three other changes in the zeitgeist reinforced that shift:

First, Jack Welch became CEO of General Electric in 1981. To deal with the long-standing concern that supervisors failed to label real differences in performance, Welch championed the forced-ranking system—another military creation. Though the U.S. Army had devised it, just before entering World War II, to quickly identify a large number of officer candidates for the country’s imminent military expansion, GE used it to shed people at the bottom. Equating performance with individuals’ inherent capabilities (and largely ignoring their potential to grow), Welch divided his workforce into “A” players, who must be rewarded; “B” players, who should be accommodated; and “C” players, who should be dismissed. In that system, development was reserved for the “A” players—the high-potentials chosen to advance into senior positions.

Second, 1993 legislation limited the tax deductibility of executive salaries to $1 million but exempted performance-based pay. That led to a rise in outcome-based bonuses for corporate leaders—a change that trickled down to frontline managers and even hourly employees—and organizations relied even more on the appraisal process to assess merit.

Third, McKinsey’s War for Talent research project in the late 1990s suggested that some employees were fundamentally more talented than others (you knew them when you saw them, the thinking went). Because such individuals were, by definition, in short supply, organizations felt they needed to take great care in tracking and rewarding them. Nothing in the McKinsey studies showed that fixed personality traits actually made certain people perform better, but that was the assumption.

So, by the early 2000s, organizations were using performance appraisals mainly to hold employees accountable and to allocate rewards. By some estimates, as many as one-third of U.S. corporations—and 60% of the Fortune 500—had adopted a forced-ranking system. At the same time, other changes in corporate life made it harder for the appraisal process to advance the time-consuming goals of improving individual performance and developing skills for future roles. Organizations got much flatter, which dramatically increased the number of subordinates that supervisors had to manage. The new norm was 15 to 25 direct reports (up from six before the 1960s). While overseeing more employees, supervisors were also expected to be individual contributors. So taking days to manage the performance issues of each employee, as Douglas McGregor had advocated, was impossible. Meanwhile, greater interest in lateral hiring reduced the need for internal development. Up to two-thirds of corporate jobs were filled from outside, compared with about 10% a generation earlier.

Back to development … again

Another major turning point came in 2005: A few years after Jack Welch left GE, the company quietly backed away from forced ranking because it fostered internal competition and undermined collaboration. Welch still defends the practice, but what he really supports is the general principle of letting people know how they are doing: “As a manager, you owe candor to your people,” he wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2013. “They must not be guessing about what the organization thinks of them.” It’s hard to argue against candor, of course. But more and more firms began questioning how useful it was to compare people with one another or even to rate them on a scale.

So the emphasis on accountability for past performance started to fade. That continued as jobs became more complex and rapidly changed shape—in that climate, it was difficult to set annual goals that would still be meaningful 12 months later. Plus, the move toward team-based work often conflicted with individual appraisals and rewards. And low inflation and small budgets for wage increases made appraisal-driven merit pay seem futile. What was the point of trying to draw performance distinctions when rewards were so trivial?

The whole appraisal process was loathed by employees anyway. Social science research showed that they hated numerical scores—they would rather be told they were “average” than given a 3 on a 5-point scale. They especially detested forced ranking. As Wharton’s Iwan Barankay demonstrated in a field setting, performance actually declined when people were rated relative to others. Nor did the ratings seem accurate. As the accumulating research on appraisal scores showed, they had as much to do with who the rater was (people gave higher ratings to those who were like them) as they did with performance.

And managers hated doing reviews, as survey after survey made clear. Willis Towers Watson found that 45% did not see value in the systems they used. Deloitte reported that 58% of HR executives considered reviews an ineffective use of supervisors’ time. In a study by the advisory service CEB, the average manager reported spending about 210 hours—close to five weeks—doing appraisals each year.

As dissatisfaction with the traditional process mounted, high-tech firms ushered in a new way of thinking about performance. The “Agile Manifesto,” created by software developers in 2001, outlined several key values—favoring, for instance, “responding to change over following a plan.” It emphasized principles such as collaboration, self-organization, self-direction, and regular reflection on how to work more effectively, with the aim of prototyping more quickly and responding in real time to customer feedback and changes in requirements. Although not directed at performance per se, these principles changed the definition of effectiveness on the job—and they were at odds with the usual practice of cascading goals from the top down and assessing people against them once a year.

So it makes sense that the first significant departure from traditional reviews happened at Adobe, in 2011. The company was already using the agile method, breaking down projects into “sprints” that were immediately followed by debriefing sessions. Adobe explicitly brought this notion of constant assessment and feedback into performance management, with frequent check-ins replacing annual appraisals. Juniper Systems, Dell, and Microsoft were prominent followers.

CEB estimated in 2014 that 12% of U.S. companies had dropped annual reviews altogether. Willis Towers Watson put the figure at 8% but added that 29% were considering eliminating them or planning to do so. Deloitte reported in 2015 that only 12% of the U.S. companies it surveyed were not planning to rethink their performance management systems. This trend seems to be extending beyond the United States as well. PwC reports that two-thirds of large companies in the UK, for example, are in the process of changing their systems.

Three Business Reasons to Drop Appraisals

In light of that history, we see three clear business imperatives that are leading companies to abandon performance appraisals:

The return of people development

Companies are under competitive pressure to upgrade their talent management efforts. This is especially true at consulting and other professional services firms, where knowledge work is the offering—and where inexperienced college grads are turned into skilled advisers through structured training. Such firms are doubling down on development, often by putting their employees (who are deeply motivated by the potential for learning and advancement) in charge of their own growth. This approach requires rich feedback from supervisors—a need that’s better met by frequent, informal check-ins than by annual reviews.

Now that the labor market has tightened and keeping good people is once again critical, such companies have been trying to eliminate “dissatisfiers” that drive employees away. Naturally, annual reviews are on that list, since the process is so widely reviled and the focus on numerical ratings interferes with the learning that people want and need to do. Replacing this system with feedback that’s delivered right after client engagements helps managers do a better job of coaching and allows subordinates to process and apply the advice more effectively.

Kelly Services was the first big professional services firm to drop appraisals, in 2011. PwC tried it with a pilot group in 2013 and then discontinued annual reviews for all 200,000-plus employees. Deloitte followed in 2015, and Accenture and KPMG made similar announcements shortly thereafter. Given the sheer size of these firms, and the fact that they offer management advice to thousands of organizations, their choices are having an enormous impact on other companies. Firms that scrap appraisals are also rethinking employee management much more broadly. Accenture CEO Pierre Nanterme estimates that his firm is changing about 90% of its talent practices.

The need for agility

When rapid innovation is a source of competitive advantage, as it is now in many companies and industries, that means future needs are continually changing. Because organizations won’t necessarily want employees to keep doing the same things, it doesn’t make sense to hang on to a system that’s built mainly to assess and hold people accountable for past or current practices. As Susan Peters, GE’s head of human resources, has pointed out, businesses no longer have clear annual cycles. Projects are short-term and tend to change along the way, so employees’ goals and tasks can’t be plotted out a year in advance with much accuracy.

At GE a new business strategy based on innovation was the biggest reason the company recently began eliminating individual ratings and annual reviews. Its new approach to performance management is aligned with its FastWorks platform for creating products and bringing them to market, which borrows a lot from agile techniques. Supervisors still have an end-of-year summary discussion with subordinates, but the goal is to push frequent conversations with employees (GE calls them “touchpoints”) and keep revisiting two basic questions: What am I doing that I should keep doing? And what am I doing that I should change? Annual goals have been replaced with shorter-term “priorities.” As with many of the companies we see, GE first launched a pilot, with about 87,000 employees in 2015, before adopting the changes across the company.

The centrality of teamwork

Moving away from forced ranking and from appraisals’ focus on individual accountability makes it easier to foster teamwork. This has become especially clear at retail companies like Sears and Gap—perhaps the most surprising early innovators in appraisals. Sophisticated customer service now requires frontline and back-office employees to work together to keep shelves stocked and manage customer flow, and traditional systems don’t enhance performance at the team level or help track collaboration.

Gap supervisors still give workers end-of-year assessments, but only to summarize performance discussions that happen throughout the year and to set pay increases accordingly. Employees still have goals, but as at other companies, the goals are short-term (in this case, quarterly). Now two years into its new system, Gap reports far more satisfaction with its performance process and the best-ever completion of store-level goals. Nonetheless, Rob Ollander-Krane, Gap’s senior director of organization performance effectiveness, says the company needs further improvement in setting stretch goals and focusing on team performance.

Implications

All three reasons for dropping annual appraisals argue for a system that more closely follows the natural cycle of work. Ideally, conversations between managers and employees occur when projects finish, milestones are reached, challenges pop up, and so forth—allowing people to solve problems in current performance while also developing skills for the future. At most companies, managers take the lead in setting near-term goals, and employees drive career conversations throughout the year. In the words of one Deloitte manager: “The conversations are more holistic. They’re about goals and strengths, not just about past performance.”

Perhaps most important, companies are overhauling performance management because their businesses require the change. That’s true whether they’re professional services firms that must develop people in order to compete, companies that need to deliver ongoing performance feedback to support rapid innovation, or retailers that need better coordination between the sales floor and the back office to serve their customers.

Of course, many HR managers worry: If we can’t get supervisors to have good conversations with subordinates once a year, how can we expect them to do so more frequently, without the support of the usual appraisal process? It’s a valid question—but we see reasons to be optimistic.

As GE found in 1964 and as research has documented since, it is extraordinarily difficult to have a serious, open discussion about problems while also dishing out consequences such as low merit pay. The end-of-year review was also an excuse for delaying feedback until then, at which point both the supervisor and the employee were likely to have forgotten what had happened months earlier. Both of those constraints disappear when you take away the annual review. Additionally, almost all companies that have dropped traditional appraisals have invested in training supervisors to talk more about development with their employees—and they are checking with subordinates to make sure that’s happening.

Moving to an informal system requires a culture that will keep the continuous feedback going. As Megan Taylor, Adobe’s director of business partnering, pointed out at a recent conference, it’s difficult to sustain that if it’s not happening organically. Adobe, which has gone totally numberless but still gives merit increases based on informal assessments, reports that regular conversations between managers and their employees are now occurring without HR’s prompting. Deloitte, too, has found that its new model of frequent, informal check-ins has led to more meaningful discussions, deeper insights, and greater employee satisfaction. (For more details, see “Reinventing Performance Management,” HBR, April 2015.) The firm started to go numberless like Adobe but then switched to assigning employees several numbers four times a year, to give them rolling feedback on different dimensions. Jeffrey Orlando, who heads up development and performance at Deloitte, says the company has been tracking the effects on business results, and they’ve been positive so far.

Challenges That Persist

The greatest resistance to abandoning appraisals, which is something of a revolution in human resources, comes from HR itself. The reason is simple: Many of the processes and systems that HR has built over the years revolve around those performance ratings. Experts in employment law had advised organizations to standardize practices, develop objective criteria to justify every employment decision, and document all relevant facts. Taking away appraisals flies in the face of that advice—and it doesn’t necessarily solve every problem that they failed to address.

The tug-of-war between accountability and development over the decades

Here are some of the challenges that organizations still grapple with when they replace the old performance model with new approaches:

Aligning individual and company goals

In the traditional model, business objectives and strategies cascaded down the organization. All the units, and then all the individual employees, were supposed to establish their goals to reflect and reinforce the direction set at the top. But this approach works only when business goals are easy to articulate and held constant over the course of a year. As we’ve discussed, that’s often not the case these days, and employee goals may be pegged to specific projects. So as projects unfold and tasks change, how do you coordinate individual priorities with the goals for the whole enterprise, especially when the business objectives are short-term and must rapidly adapt to market shifts? It’s a new kind of problem to solve, and the jury is still out on how to respond.

Rewarding performance

Appraisals gave managers a clear-cut way of tying rewards to individual contributions. Companies changing their systems are trying to figure out how their new practices will affect the pay-for-performance model, which none of them have explicitly abandoned.

They still differentiate rewards, usually relying on managers’ qualitative judgments rather than numerical ratings. In pilot programs at Juniper Systems and Cargill, supervisors had no difficulty allocating merit-based pay without appraisal scores. In fact, both line managers and HR staff felt that paying closer attention to employee performance throughout the year was likely to make their merit-pay decisions more valid.

But it will be interesting to see whether most supervisors end up reviewing the feedback they’ve given each employee over the year before determining merit increases. (Deloitte’s managers already do this.) If so, might they produce something like an annual appraisal score—even though it’s more carefully considered? And could that subtly undermine development by shifting managers’ focus back to accountability?

Identifying poor performers

Though managers may assume they need appraisals to determine which employees aren’t doing their jobs well, the traditional process doesn’t really help much with that. For starters, individuals’ ratings jump around over time. Research shows that last year’s performance score predicts only one-third of the variance in this year’s score—so it’s hard to say that someone simply isn’t up to scratch. Plus, HR departments consistently complain that line managers don’t use the appraisal process to document poor performers. Even when they do, waiting until the end of the year to flag struggling employees allows failure to go on for too long without intervention.

We’ve observed that companies that have dropped appraisals are requiring supervisors to immediately identify problem employees. Juniper Systems also formally asks supervisors each quarter to confirm that their subordinates are performing up to company standards. Only 3%, on average, are not, and HR is brought in to address them. Adobe reports that its new system has reduced dismissals, because struggling employees are monitored and coached much more closely.

Still, given how reluctant most managers are to single out failing employees, we can’t assume that getting rid of appraisals will make those tough calls any easier. And all the companies we’ve observed still have “performance improvement plans” for employees identified as needing support. Such plans remain universally problematic, too, partly because many issues that cause poor performance can’t be solved by management intervention.

Avoiding legal troubles

Employee relations managers within HR often worry that discrimination charges will spike if their companies stop basing pay increases and promotions on numerical ratings, which seem objective. But appraisals haven’t prevented discriminatory practices. Though they force managers to systematically review people’s contributions each year, a great deal of discretion (always subject to bias) is built into the process, and considerable evidence shows that supervisors discriminate against some employees by giving them undeservedly low ratings.

Leaders at Gap report that their new practices were driven partly by complaints and research showing that the appraisal process was often biased and ineffective. Frontline workers in retail (disproportionately women and minorities) are especially vulnerable to unfair treatment. Indeed, formal ratings may do more to reveal bias than to curb it. If a company has clear appraisal scores and merit-pay indexes, it is easy to see if women and minorities with the same scores as white men are getting fewer or lower pay increases.

All that said, it’s not clear that new approaches to performance management will do much to mitigate discrimination either. (See the sidebar “Can You Take Cognitive Bias Out of Assessments?”) Gap has found that getting rid of performance scores increased fairness in pay and other decisions, but judgments still have to be made—and there’s the possibility of bias in every piece of qualitative information that decision makers consider.

Managing the feedback firehose

In recent years most HR information systems were built to move annual appraisals online and connect them to pay increases, succession planning, and so forth. They weren’t designed to accommodate continuous feedback, which is one reason many employee check-ins consist of oral comments, with no documentation.

The tech world has responded with apps that enable supervisors to give feedback anytime and to record it if desired. At General Electric, the PD@GE app (“PD” stands for “performance development”) allows managers to call up notes and materials from prior conversations and summarize that information. Employees can use the app to ask for direction when they need it. IBM has a similar app that adds another feature: It enables employees to give feedback to peers and choose whether the recipient’s boss gets a copy. Amazon’s Anytime Feedback tool does much the same thing. The great advantage of these apps is that supervisors can easily review all the discussion text when it is time to take actions such as award merit pay or consider promotions and job reassignments.

Of course, being on the receiving end of all that continual coaching could get overwhelming—it never lets up. And as for peer feedback, it isn’t always useful, even if apps make it easier to deliver in real time. Typically, it’s less objective than supervisor feedback, as anyone familiar with 360s knows. It can be also “gamed” by employees to help or hurt colleagues. (At Amazon, the cutthroat culture encourages employees to be critical of one another’s performance, and forced ranking creates an incentive to push others to the bottom of the heap.) The more consequential the peer feedback, the more likely the problems.

Not all employers face the same business pressures to change their performance processes. In some fields and industries (think sales and financial services), it still makes sense to emphasize accountability and financial rewards for individual performers. Organizations with a strong public mission may also be well served by traditional appraisals. But even government organizations like NASA and the FBI are rethinking their approach, having concluded that accountability should be collective and that supervisors need to do a better job of coaching and developing their subordinates.

Ideology at the top matters. Consider what happened at Intel. In a two-year pilot, employees got feedback but no formal appraisal scores. Though supervisors did not have difficulty differentiating performance or distributing performance-based pay without the ratings, company executives returned to using them, believing they created healthy competition and clear outcomes. At Sun Communities, a manufactured-home company, senior leaders also oppose eliminating appraisals because they think formal feedback is essential to accountability. And Medtronic, which gave up ratings several years ago, is resurrecting them now that it has acquired Ireland-based Covidien, which has a more traditional view of performance management.

Other firms aren’t completely reverting to old approaches but instead seem to be seeking middle ground. As we’ve mentioned, Deloitte has backpedaled from giving no ratings at all to having project leads and managers assign them in four categories on a quarterly basis, to provide detailed “performance snapshots.” PwC recently made a similar move in its client-services practices: Employees still don’t receive a single rating each year, but they now get scores on five competencies, along with other development feedback. In PwC’s case, the pushback against going numberless actually came from employees, especially those on a partner track, who wanted to know how they were doing.

At one insurance company, after formal ratings had been eliminated, merit-pay increases were being shared internally and then interpreted as performance scores. These became known as “shadow ratings,” and because they started to affect other talent management decisions, the company eventually went back to formal appraisals. But it kept other changes it had made to its performance management system, such as quarterly conversations between managers and employees, to maintain its new commitment to development.

It will be interesting to see how well these “third way” approaches work. They, too, could fail if they aren’t supported by senior leadership and reinforced by organizational culture. Still, in most cases, sticking with old systems seems like a bad option. Companies that don’t think an overhaul makes sense for them should at least carefully consider whether their process is giving them what they need to solve current performance problems and develop future talent. Performance appraisals wouldn’t be the least popular practice in business, as they’re widely believed to be, if something weren’t fundamentally wrong with them.