by Francesca Gino

THROUGHOUT OUR CAREERS, we are taught to conform—to the status quo, to the opinions and behaviors of others, and to information that supports our views. The pressure only grows as we climb the organizational ladder. By the time we reach high-level positions, conformity has been so hammered into us that we perpetuate it in our enterprises. In a recent survey I conducted of more than 2,000 employees across a wide range of industries, nearly half the respondents reported working in organizations where they regularly feel the need to conform, and more than half said that people in their organizations do not question the status quo. The results were similar when I surveyed high-level executives and midlevel managers. As this data suggests, organizations consciously or unconsciously urge employees to check a good chunk of their real selves at the door. Workers and their organizations both pay a price: decreased engagement, productivity, and innovation (see the exhibit “The perils of conformity”).

Drawing on my research and fieldwork and on the work of other scholars of psychology and management, I will describe three reasons for our conformity on the job, discuss why this behavior is costly for organizations, and suggest ways to combat it.

Of course, not all conformity is bad. But to be successful and evolve, organizations need to strike a balance between adherence to the formal and informal rules that provide necessary structure and the freedom that helps employees do their best work. The pendulum has swung too far in the direction of conformity. In another recent survey I conducted, involving more than 1,000 employees in a variety of industries, less than 10% said they worked in companies that regularly encourage nonconformity. That’s not surprising: For decades the principles of scientific management have prevailed. Leaders have been overly focused on designing efficient processes and getting employees to follow them. Now they need to think about when conformity hurts their business and allow—even promote—what I call constructive nonconformity: behavior that deviates from organizational norms, others’ actions, or common expectations, to the benefit of the organization.

Why Conformity Is So Prevalent

Let’s look at the three main, and interrelated, reasons why we so often conform at work.

We fall prey to social pressure

Early in life we learn that tangible benefits arise from following social rules about what to say, how to act, how to dress, and so on. Conforming makes us feel accepted and part of the majority. As classic research conducted in the 1950s by the psychologist Solomon Asch showed, conformity to peer pressure is so powerful that it occurs even when we know it will lead us to make bad decisions. In one experiment, Asch asked participants to complete what they believed was a simple perceptual task: identifying which of three lines on one card was the same length as a line on another card. When asked individually, participants chose the correct line. When asked in the presence of paid actors who intentionally selected the wrong line, about 75% conformed to the group at least once. In other words, they chose an incorrect answer in order to fit in.

Organizations have long exploited this tendency. Ancient Roman families employed professional mourners at funerals. Entertainment companies hire people (“claques”) to applaud at performances. And companies advertising health products often report the percentage of doctors or dentists who use their offerings.

Conformity at work takes many forms: modeling the behavior of others in similar roles, expressing appropriate emotions, wearing proper attire, routinely agreeing with the opinions of managers, acquiescing to a team’s poor decisions, and so on. And all too often, bowing to peer pressure reduces individuals’ engagement with their jobs. This is understandable: Conforming often conflicts with our true preferences and beliefs and therefore makes us feel inauthentic. In fact, research I conducted with Maryam Kouchaki, of Northwestern University, and Adam Galinsky, of Columbia University, showed that when people feel inauthentic at work, it’s usually because they have succumbed to social pressure to conform.

We become too comfortable with the status quo

In organizations, standard practices—the usual ways of thinking and doing—play a critical role in shaping performance over time. But they can also get us stuck, decrease our engagement, and constrain our ability to innovate or to perform at a high level. Rather than resulting from thoughtful choices, many traditions endure out of routine, or what psychologists call the status quo bias. Because we feel validated and reassured when we stick to our usual ways of thinking and doing, and because—as research has consistently found—we weight the potential losses of deviating from the status quo much more heavily than we do the potential gains, we favor decisions that maintain the current state of affairs.

But sticking with the status quo can lead to boredom, which in turn can fuel complacency and stagnation. Borders, BlackBerry, Polaroid, and Myspace are but a few of the many companies that once had winning formulas but didn’t update their strategies until it was too late. Overly comfortable with the status quo, their leaders fell back on tradition and avoided the type of nonconformist behavior that could have spurred continued success.

We interpret information in a self-serving manner

A third reason for the prevalence of conformity is that we tend to prioritize information that supports our existing beliefs and to ignore information that challenges them, so we overlook things that could spur positive change. Complicating matters, we also tend to view unexpected or unpleasant information as a threat and to shun it—a phenomenon psychologists call motivated skepticism.

In fact, research suggests, the manner in which we weigh evidence resembles the manner in which we weigh ourselves on a bathroom scale. If the scale delivers bad news, we hop off and get back on—perhaps the scale misfired or we misread the display. If it delivers good news, we assume it’s correct and cheerfully head for the shower.

Here’s a more scientific example. Two psychologists, Peter Ditto and David Lopez, asked study participants to evaluate a student’s intelligence by reviewing information about him one piece at a time—similar to the way college admissions officers evaluate applicants. The information was quite negative. Subjects could stop going through it as soon as they’d reached a firm conclusion. When they had been primed to like the student (with a photo and some information provided before the evaluation), they turned over one card after another, searching for anything that would allow them to give a favorable rating. When they had been primed to dislike him, they turned over a few cards, shrugged, and called it a day.

By uncritically accepting information when it is consistent with what we believe and insisting on more when it isn’t, we subtly stack the deck against good decisions.

Promoting Constructive Nonconformity

Few leaders actively encourage deviant behavior in their employees; most go to great lengths to get rid of it. Yet nonconformity promotes innovation, improves performance, and can enhance a person’s standing more than conformity can. For example, research I conducted with Silvia Bellezza, of Columbia, and Anat Keinan, of Harvard, showed that observers judge a keynote speaker who wears red sneakers, a CEO who makes the rounds of Wall Street in a hoodie and jeans, and a presenter who creates her own PowerPoint template rather than using her company’s as having higher status than counterparts who conform to business norms.

My research also shows that going against the crowd gives us confidence in our actions, which makes us feel unique and engaged and translates to higher performance and greater creativity. In one field study, I asked a group of employees to behave in nonconforming ways (speaking up if they disagreed with colleagues’ decisions, expressing what they felt rather than what they thought they were expected to feel, and so on). I asked another group to behave in conforming ways, and a third group to do whatever its members usually did. After three weeks, those in the first group reported feeling more confident and engaged in their work than those in the other groups. They displayed more creativity in a task that was part of the study. And their supervisors gave them higher ratings on performance and innovativeness.

Six strategies can help leaders encourage constructive nonconformity in their organizations and themselves.

Step 1: Give Employees Opportunities to Be Themselves

Decades’ worth of psychological research has shown that we feel accepted and believe that our views are more credible when our colleagues share them. But although conformity may make us feel good, it doesn’t let us reap the benefits of authenticity. In one study Dan Cable, of London Business School, and Virginia Kay, then of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, surveyed 154 recent MBA graduates who were four months into their jobs. Those who felt they could express their authentic selves at work were, on average, 16% more engaged and more committed to their organizations than those who felt they had to hide their authentic selves. In another study, Cable and Kay surveyed 2,700 teachers who had been working for a year and reviewed the performance ratings given by their supervisors. Teachers who said they could express their authentic selves received higher ratings than teachers who did not feel they could do so.

Here are some ways to help workers be true to themselves:

Encourage employees to reflect on what makes them feel authentic. This can be done from the very start of the employment relationship—during orientation. In a field study I conducted with Brad Staats, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Dan Cable, employees in the business-process-outsourcing division of the Indian IT company Wipro went through a slightly modified onboarding process. We gave them a half hour to think about what was unique about them, what made them authentic, and how they could bring out their authentic selves at work. Later we compared them with employees who had gone through Wipro’s usual onboarding program, which allowed no time for such reflection. The employees in the first group had found ways to tailor their jobs so that they could be their true selves—for example, they exercised judgment when answering calls instead of rigidly following the company script. They were more engaged in their work, performed better, and were more likely to be with the company seven months later.

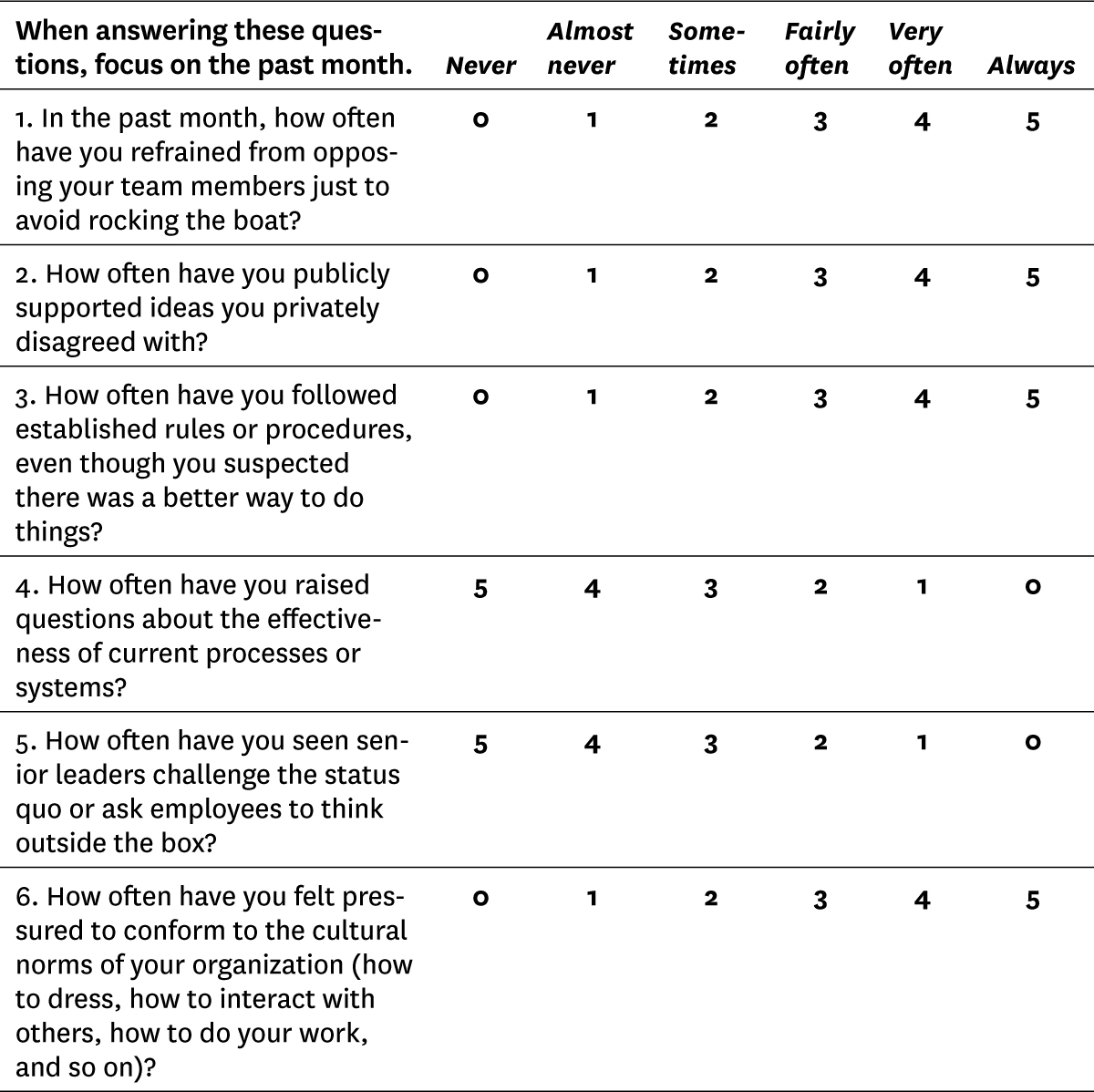

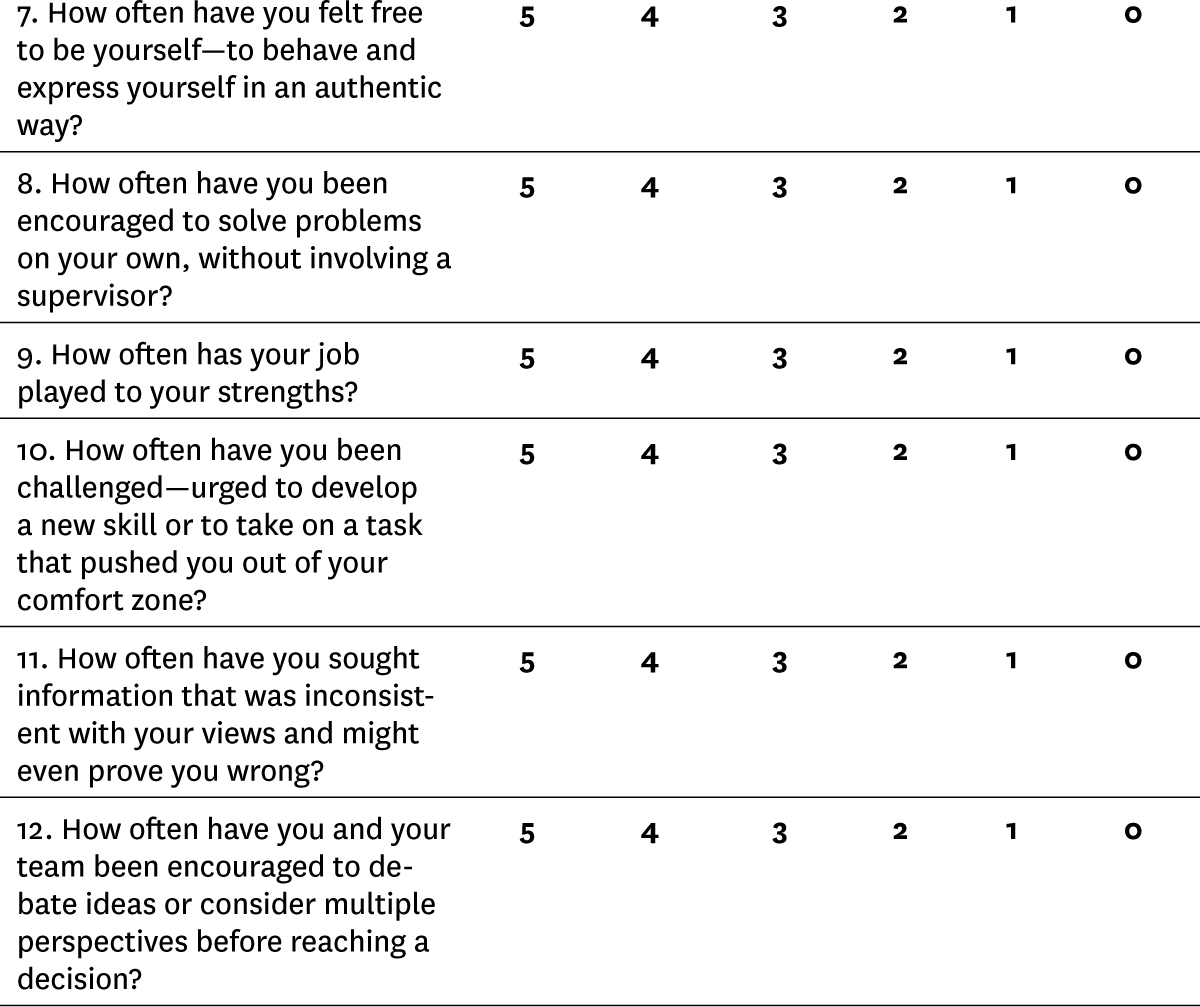

The perils of conformity

Organizations put tremendous pressure on employees to conform. In a recent survey of 2,087 U.S. employees in a wide range of industries, nearly 49% agreed with the statement “I regularly feel pressure to conform in this organization.”

This takes a heavy toll on individuals and enterprises alike. Employees who felt a need to conform reported a less positive work experience on several dimensions than did other employees, as shown by the average scores plotted below.

Leaders can also encourage this type of reflection once people are on the job. The start of a new year is a natural time for employees and their leaders to reflect on what makes them unique and authentic and how they can shape their jobs—even in small ways—to avoid conformity. Reflection can also be encouraged at other career points, such as a performance review, a promotion, or a transition into a new role.

Tell employees what job needs to be done rather than how to do it. When Colleen Barrett was executive vice president of Southwest Airlines, from 1990 to 2001, she established the goal of allowing employees to be themselves. For example, flight attendants were encouraged to deliver the legally required safety announcement in their own style and with humor. “We have always thought that your avocation can be your vocation so that you don’t have to do any acting in your life when you leave home to go to work,” she has said. This philosophy helped make Southwest a top industry performer in terms of passenger volume, profitability, customer satisfaction, and turnover.

Let employees solve problems on their own. Leaders can encourage authenticity by allowing workers to decide how to handle certain situations. For instance, in the 1990s British Airways got rid of its thick customer-service handbook and gave employees the freedom (within reason) to figure out how to deal with customer problems as they arose (see “Competing on Customer Service: An Interview with British Airways’ Sir Colin Marshall,” HBR, November–December 1995).

Another company that subscribes to this philosophy is Pal’s Sudden Service, a fast-food chain in the southern United States. By implementing lean principles, including the idea that workers are empowered to call out and fix problems, Pal’s has achieved impressive numbers: one car served at the drive-through every 18 seconds, one mistake in every 3,600 orders (the industry average is one in 15), customer satisfaction scores of 98%, and health inspection scores above 97%. Turnover at the assistant manager level is under 2%, and in three decades Pal’s has lost only seven general managers—two of them to retirement. Annual turnover on the front lines is about 34%—half the industry average. Pal’s trains its employees extensively: New frontline workers receive 135 hours of instruction, on average (the industry average is about two hours). As a result, employees are confident that they can solve problems on their own and can stop processes if something does not seem right. (They also know they can ask for help.) When I was conducting interviews for a case on Pal’s, a general manager gave me an example of how he encourages frontline workers to make decisions themselves: “A 16-year-old [employee] shows me a hot dog bun with flour on it and asks me if it’s OK. My response: ‘Your call. Would you sell it?’”

Let employees define their missions. Morning Star, a California-based tomato processing company, has employees write “personal commercial mission statements” that reflect who they are and specify their goals for a given time period, ones that will contribute to the company’s success. The statements are embedded in contracts known as “colleague letters of understanding,” or CLOUs, which employees negotiate with coworkers, each spelling out how he or she will collaborate with others. The personal commercial mission of Morning Star’s founder, Chris Rufer, is “to advance tomato technology to be the best in the world and operate these factories so they are pristine.” That of one sales and marketing employee is “to indelibly mark ‘Morning Star Tomato Products’ on the tongue and brain of every commercial tomato product user.” That of one employee in the shipping unit is “to reliably and efficiently provide our customers with marvelously attractive loads of desired product.”

Step 2: Encourage Employees to Bring Out Their Signature Strengths

Michelangelo described sculpting as a process whereby the artist releases an ideal figure from the block of stone in which it slumbers. We all possess ideal forms, the signature strengths—being social connectors, for example, or being able to see the positive in any situation—that we use naturally in our lives. And we all have a drive to do what we do best and be recognized accordingly. A leader’s task is to encourage employees to sculpt their jobs to bring out their strengths—and to sculpt his or her own job, too. The actions below can help.

Give employees opportunities to identify their strengths. In a research project I conducted with Dan Cable, Brad Staats, and the University of Michigan’s Julia Lee, leaders of national and local government agencies across the globe reflected each morning on their signature strengths and how to use them. They also read descriptions of times when they were at their best, written by people in their personal and professional networks. These leaders displayed more engagement and innovative behavior than members of a control group, and their teams performed better.

Tailor jobs to employees’ strengths. Facebook is known for hiring smart people regardless of the positions currently open in the company, gathering information about their strengths, and designing their jobs accordingly. Another example is Osteria Francescana, a Michelin three-star restaurant in Modena, Italy, that won first place in the 2016 World’s 50 Best Restaurant awards. Most restaurants, especially top-ranked ones, observe a strict hierarchy, with specific titles for each position. But at Osteria Francescana, jobs and their attendant responsibilities are tailored to individual workers.

Discovering employees’ strengths takes time and effort. Massimo Bottura, the owner and head chef, rotates interns through various positions for at least a few months so that he and his team can configure jobs to play to the newcomers’ strengths. This ensures that employees land where they fit best.

If such a process is too ambitious for your organization, consider giving employees some freedom to choose responsibilities within their assigned roles.

Step 3: Question the Status Quo, and Encourage Employees to Do the Same

Although businesses can benefit from repeatable practices that ensure consistency, they can also stimulate employee engagement and innovation by questioning standard procedures—“the way we’ve always done it.” Here are some proven tactics.

Ask “Why?” and “What if?” By regularly asking employees such questions, Max Zanardi, for several years the general manager of the Ritz-Carlton in Istanbul, creatively led them to redefine luxury by providing customers with authentic and unusual experiences. For example, employees had traditionally planted flowers each year on the terrace outside the hotel’s restaurant. One day Zanardi asked, “Why do we always plant flowers? How about vegetables? What about herbs?” This resulted in a terrace garden featuring herbs and heirloom tomatoes used in the restaurant—things guests very much appreciated.

Leaders who question the status quo give employees reasons to stay engaged and often spark fresh ideas that can rejuvenate the business.

Stress that the company is not perfect. Ed Catmull, the cofounder and president of Pixar Animation Studios, worried that new hires would be too awed by Pixar’s success to challenge existing practices (see “How Pixar Fosters Collective Creativity,” HBR, September 2008). So during onboarding sessions, his speeches included examples of the company’s mistakes. Emphasizing that we are all human and that the organization will never be perfect gives employees freedom to engage in constructive nonconformity.

Excel at the basics. Ensuring that employees have deep knowledge about the way things usually operate provides them with a foundation for constructively questioning the status quo. This philosophy underlies the many hours Pal’s devotes to training: Company leaders want employees to be expert in all aspects of their work. Similarly, Bottura believes that to create innovative dishes, his chefs must be well versed in classic cooking techniques.

Step 4: Create Challenging Experiences

It’s easy for workers to get bored and fall back on routine when their jobs involve little variety or challenge. And employees who find their work boring lack the motivation to perform well and creatively, whereas work that is challenging enhances their engagement. Research led by David H. Zald, of Vanderbilt University, shows that novel behavior, such as trying something new or risky, triggers the release of dopamine, a chemical that helps keep us motivated and eager to innovate.

Leaders can draw on the following tactics when structuring employees’ jobs:

Maximize variety. This makes it less likely that employees will go on autopilot and more likely that they will come up with innovative ways to improve what they’re doing. It also boosts performance, as Brad Staats and I found in our analysis of two and a half years’ worth of transaction data from a Japanese bank department responsible for processing home loan applications. The mortgage line involved 17 distinct tasks, including scanning applications, comparing scanned documents to originals, entering application data into the computer system, assessing whether information complied with underwriting standards, and conducting credit checks. Workers who were assigned diverse tasks from day to day were more productive than others (as measured by the time taken to complete each task); the variety kept them motivated. This allowed the bank to process applications more quickly, increasing its competitiveness.

Variety can be ensured in a number of ways. Pal’s rotates employees through tasks (taking orders, grilling, working the register, and so on) in a different order each day. Some companies forgo defined career trajectories and instead move employees through various positions within departments or teams over the course of months or years.

In addition to improving engagement, job rotation broadens individuals’ skill sets, creating a more flexible workforce. This makes it easier to find substitutes if someone falls ill or abruptly quits and to shift people from tasks where they are no longer needed (see “Why ‘Good Jobs’ Are Good for Retailers,” HBR, January–February 2012).

Continually inject novelty into work. Novelty is a powerful force. When something new happens at work, we pay attention, engage, and tend to remember it. We are less likely to take our work for granted when it continues to generate strong feelings. Novelty in one’s job is more satisfying than stability.

So, how can leaders inject it into work? Bottura throws last-minute menu changes at his team to keep excitement high. At Pal’s, employees learn the order of their tasks for the day only when they get to work.

Leaders can also introduce novelty by making sure that projects include a few people who are somewhat out of their comfort zone, or by periodically giving teams new challenges (for instance, asking them to deliver a product faster than in the past). They can assign employees to teams charged with designing a new work process or piloting a new service.

Identify opportunities for personal learning and growth. Giving people such experiences is an essential way to promote constructive nonconformity, research has shown. For instance, in a field study conducted at a global consulting firm, colleagues and I found that when onboarding didn’t just focus on performance but also spotlighted opportunities for learning and growth, engagement and innovative behaviors were higher six months later. Companies often identify growth opportunities during performance reviews, of course, but there are many other ways to do so. Chefs at Osteria Francescana can accompany Bottura to cooking events that expose them to other countries, cuisines, traditions, arts, and culture—all potential sources of inspiration for new dishes. When I worked as a research consultant at Disney, in the summer of 2010, I learned that members of the Imagineering R&D group were encouraged to belong to professional societies, attend conferences, and publish in academic and professional journals. Companies can help pay for courses that may not strictly relate to employees’ current jobs but would nonetheless expand their skill sets or fuel their curiosity.

Give employees responsibility and accountability. At Morning Star, if employees need new equipment to do their work—even something that costs thousands of dollars—they may buy it. If they see a process that would benefit from different skills, they may hire someone. They must consult colleagues who would be affected (other people who would use the equipment, say), but they don’t need approval from above. Because there are no job titles at Morning Star, how employees influence others—and thus get work done—is determined mainly by how their colleagues perceive the quality of their decisions.

Step 5: Foster Broader Perspectives

We often focus so narrowly on our own point of view that we have trouble understanding others’ experiences and perspectives. And as we assume high-level positions, research shows, our egocentric focus becomes stronger. Here are some ways to combat it:

Create opportunities for employees to view problems from multiple angles. We all tend to be self-serving in terms of how we process information and generate (or fail to generate) alternatives to the status quo. Leaders can help employees overcome this tendency by encouraging them to view problems from different perspectives. At the electronics manufacturer Sharp, an oft-repeated maxim is “Be dragonflies, not flatfish.” Dragonflies have compound eyes that can take in multiple perspectives at once; flatfish have both eyes on the same side of the head and can see in only one direction at a time.

Jon Olinto and Anthony Ackil, the founders of the fast-casual restaurant chain b.good, require all employees (including managers) and franchisees to be trained in every job—from prep to grill to register. (Unlike Pal’s, however, b.good does not rotate people through jobs each day.) Being exposed to different perspectives increases engagement and innovative behaviors, research has found.

Use language that reduces self-serving bias. To prevent their traders from letting success go to their heads when the market is booming, some Wall Street firms regularly remind them, “Don’t confuse brains with a bull market.” At GE, terms such as “planting seeds” (to describe making investments that will produce fruitful results even after the managers behind them have moved on to other jobs) have entered the lexicon (see “How GE Teaches Teams to Lead Change,” HBR, January 2009).

Hire people with diverse perspectives. Decades’ worth of research has found that working among people from a variety of cultures and backgrounds helps us see problems in new ways and consider ideas that might otherwise go unnoticed, and it fosters the kind of creativity that champions change. At Osteria Francescana the two sous-chefs are Kondo “Taka” Takahiko, from Japan, and Davide di-Fabio, from Italy. They differ not only in country of origin but also in strengths and ways of thinking: Davide is comfortable with improvisation, for example, while Taka is obsessed with precision. Diversity in ways of thinking is a quality sought by Rachael Chong, the founder and CEO of the startup Catchafire. When interviewing job candidates, she describes potential challenges and carefully listens to see whether people come up with many possible solutions or get stuck on a single one. To promote innovation and new approaches, Ed Catmull hires prominent outsiders, gives them important roles, and publicly acclaims their contributions. But many organizations do just the opposite: hire people whose thinking mirrors that of the current management team.

Step 6: Voice and Encourage Dissenting Views

We often seek out and fasten on information that confirms our beliefs. Yet data that is inconsistent with our views and may even generate negative feelings (such as a sense of failure) can provide opportunities to improve our organizations and ourselves. Leaders can use a number of tactics to push employees out of their comfort zones.

Look for disconfirming evidence. Leaders shouldn’t ask, “Who agrees with this course of action?” or “What information supports this view?” Instead they should ask, “What information suggests this might not be the right path to take?” Mellody Hobson, the president of Ariel Investments and the chair of the board of directors of DreamWorks Animation, regularly opens team meetings by reminding attendees that they don’t need to be right; they need to bring up information that can help the team make the right decisions, which happens when members voice their concerns and disagree. At the Chicago Board of Trade, in-house investigators scrutinize trades that may violate exchange rules. To avoid bias in collecting information, they have been trained to ask open-ended interview questions, not ones that can be answered with a simple yes or no. Leaders can use a similar approach when discussing decisions. They should also take care not to depend on opinions but to assess whether the data supports or undermines the prevailing point of view.

Create dissent by default. Leaders can encourage debate during meetings by inviting individuals to take opposing points of view; they can also design processes to include dissent. When employees of Pal’s suggest promising ideas for new menu items, the ideas are tested in three different stores: one whose owner-operator likes the idea (“the protagonist”), one whose owner-operator is skeptical (“the antagonist”), and one whose owner-operator has yet to form a strong opinion (“the neutral”). This ensures that dissenting views are aired and that they help inform the CEO’s decisions about proposed items.

Identify courageous dissenters. Even if encouraged to push back, many timid or junior people won’t. So make sure the team includes people you know will voice their concerns, writes Diana McLain Smith in The Elephant in the Room: How Relationships Make or Break the Success of Leaders and Organizations. Once the more reluctant employees see that opposing views are welcome, they will start to feel comfortable dissenting as well.

Striking the Right Balance

By adopting the strategies above, leaders can fight their own and their employees’ tendency to conform when that would hurt the company’s interests. But to strike the optimal balance between conformity and nonconformity, they must think carefully about the boundaries within which employees will be free to deviate from the status quo. For instance, the way a manager leads her team can be up to her as long as her behavior is aligned with the company’s purpose and values and she delivers on that purpose.

Morning Star’s colleague letters of understanding provide such boundaries. They clearly state employees’ goals and their responsibility to deliver on the organization’s purpose but leave it up to individual workers to decide how to achieve those goals. Colleagues with whom an employee has negotiated a CLOU will let him know if his actions cross a line.

Brazil’s Semco Group, a 3,000-employee conglomerate, similarly relies on peer pressure and other mechanisms to give employees considerable freedom while making sure they don’t go overboard. The company has no job titles, dress code, or organizational charts. If you need a workspace, you reserve it in one of a few satellite offices scattered around São Paulo. Employees, including factory workers, set their own schedules and production quotas. They even choose the amount and form of their compensation. What prevents employees from taking advantage of this freedom? First, the company believes in transparency: All its financial information is public, so everyone knows what everyone else makes. People who pay themselves too much have to work with resentful colleagues. Second, employee compensation is tied directly to company profits, creating enormous peer pressure to keep budgets in line.

Ritz-Carlton, too, excels in balancing conformity and nonconformity. It depends on 3,000 standards developed over the years to ensure a consistent customer experience at all its hotels. These range from how to slice a lime to which toiletries to stock in the bathrooms. But employees have considerable freedom within those standards and can question them if they see ways to provide an even better customer experience. For instance, for many years the company has allowed staff members to spend up to $2,000 to address any customer complaint in the way they deem best. (Yes, that is $2,000 per employee per guest.) The hotel believes that business is most successful when employees have well-defined standards, understand the reasoning behind them, and are given autonomy in carrying them out.

Organizations, like individuals, can easily become complacent, especially when business is going well. Complacency often sets in because of too much conformity—stemming from peer pressure, acceptance of the status quo, and the interpretation of information in self-serving ways. The result is a workforce of people who feel they can’t be themselves on the job, are bored, and don’t consider others’ points of view.

Constructive nonconformity can help companies avoid these problems. If leaders were to put just half the time they spend ensuring conformity into designing and installing mechanisms to encourage constructive deviance, employee engagement, productivity, and innovation would soar.

Originally published in October–November 2016. Reprint H035GG