The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership

by Joseph L. Bower and Lynn S. Paine

IN THE FALL OF 2014, the hedge fund activist and Allergan shareholder Bill Ackman became increasingly frustrated with Allergan’s board of directors. In a letter to the board, he took the directors to task for their failure to do (in his words) “what you are paid $400,000 per year to do on behalf of the Company’s owners.” The board’s alleged failure: refusing to negotiate with Valeant Pharmaceuticals about its unsolicited bid to take over Allergan—a bid that Ackman himself had helped engineer in a novel alliance between a hedge fund and a would-be acquirer. In presentations promoting the deal, Ackman praised Valeant for its shareholder-friendly capital allocation, its shareholder-aligned executive compensation, and its avoidance of risky early-stage research. Using the same approach at Allergan, he told analysts, would create significant value for its shareholders. He cited Valeant’s plan to cut Allergan’s research budget by 90% as “really the opportunity.” Valeant CEO Mike Pearson assured analysts that “all we care about is shareholder value.”

These events illustrate a way of thinking about the governance and management of companies that is now pervasive in the financial community and much of the business world. It centers on the idea that management’s objective is, or should be, maximizing value for shareholders, but it addresses a wide range of topics—from performance measurement and executive compensation to shareholder rights, the role of directors, and corporate responsibility. This thought system has been embraced not only by hedge fund activists like Ackman but also by institutional investors more generally, along with many boards, managers, lawyers, academics, and even some regulators and lawmakers. Indeed, its precepts have come to be widely regarded as a model for “good governance” and for the brand of investor activism illustrated by the Allergan story.

Yet the idea that corporate managers should make maximizing shareholder value their goal—and that boards should ensure that they do—is relatively recent. It is rooted in what’s known as agency theory, which was put forth by academic economists in the 1970s. At the theory’s core is the assertion that shareholders own the corporation and, by virtue of their status as owners, have ultimate authority over its business and may legitimately demand that its activities be conducted in accordance with their wishes.

Attributing ownership of the corporation to shareholders sounds natural enough, but a closer look reveals that it is legally confused and, perhaps more important, involves a challenging problem of accountability. Keep in mind that shareholders have no legal duty to protect or serve the companies whose shares they own and are shielded by the doctrine of limited liability from legal responsibility for those companies’ debts and misdeeds. Moreover, they may generally buy and sell shares without restriction and are required to disclose their identities only in certain circumstances. In addition, they tend to be physically and psychologically distant from the activities of the companies they invest in. That is to say, public company shareholders have few incentives to consider, and are not generally viewed as responsible for, the effects of the actions they favor on the corporation, other parties, or society more broadly. Agency theory has yet to grapple with the implications of the accountability vacuum that results from accepting its central—and in our view, faulty—premise that shareholders own the corporation.

The effects of this omission are troubling. We are concerned that the agency-based model of governance and management is being practiced in ways that are weakening companies and—if applied even more widely, as experts predict—could be damaging to the broader economy. In particular we are concerned about the effects on corporate strategy and resource allocation. Over the past few decades the agency model has provided the rationale for a variety of changes in governance and management practices that, taken together, have increased the power and influence of certain types of shareholders over other types and further elevated the claims of shareholders over those of other important constituencies—without establishing any corresponding responsibility or accountability on the part of shareholders who exercise that power. As a result, managers are under increasing pressure to deliver ever faster and more predictable returns and to curtail riskier investments aimed at meeting future needs and finding creative solutions to the problems facing people around the world.

Don’t misunderstand: We are capitalists to the core. We believe that widespread participation in the economy through the ownership of stock in publicly traded companies is important to the social fabric, and that strong protections for shareholders are essential. But the health of the economic system depends on getting the role of shareholders right. The agency model’s extreme version of shareholder centricity is flawed in its assumptions, confused as a matter of law, and damaging in practice. A better model would recognize the critical role of shareholders but also take seriously the idea that corporations are independent entities serving multiple purposes and endowed by law with the potential to endure over time. And it would acknowledge accepted legal principles holding that directors and managers have duties to the corporation as well as to shareholders. In other words, a better model would be more company centered.

Before considering an alternative, let’s take a closer look at the agency-based model.

Foundations of the Model

The ideas underlying the agency-based model can be found in Milton Friedman’s well-known New York Times Magazine article of 1970 denouncing corporate “social responsibility” as a socialist doctrine. Friedman takes shareholders’ ownership of the corporation as a given. He asserts that “the manager is the agent of the individuals who own the corporation” and, further, that the manager’s primary “responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with [the owners’] desires.” He characterizes the executive as “an agent serving the interests of his principal.”

These ideas were further developed in the 1976 Journal of Financial Economics article “Theory of the Firm,” by Michael Jensen and William Meckling, who set forth the theory’s basic premises:

Shareholders own the corporation and are “principals” with original authority to manage the corporation’s business and affairs.

Managers are delegated decision-making authority by the corporation’s shareholders and are thus “agents” of the shareholders.

As agents of the shareholders, managers are obliged to conduct the corporation’s business in accordance with shareholders’ desires.

Shareholders want business to be conducted in a way that maximizes their own economic returns. (The assumption that shareholders are unanimous in this objective is implicit throughout the article.)

Jensen and Meckling do not discuss shareholders’ wishes regarding the ethical standards that managers should observe in conducting the business, but Friedman offers two views in his Times article. First he writes that shareholders generally want managers “to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” Later he suggests that shareholders simply want managers to use resources and pursue profit by engaging “in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” Jensen and Meckling agree with Friedman that companies should not engage in acts of “social responsibility.”

Much of the academic work on agency theory in the decades since has focused on ensuring that managers seek to maximize shareholder returns—primarily by aligning their interests with those of shareholders. These ideas have been further developed into a theory of organization whereby managers can (and should) instill concern for shareholders’ interests throughout a company by properly delegating “decision rights” and creating appropriate incentives. They have also given rise to a view of boards of directors as an organizational mechanism for controlling what’s known as “agency costs”—the costs to shareholders associated with delegating authority to managers. Hence the notion that a board’s principal role is (or should be) monitoring management, and that boards should design executive compensation to align management’s interests with those of shareholders.

The Model’s Flaws

Let’s look at where these ideas go astray.

1. Agency theory is at odds with corporate law: Legally, shareholders do not have the rights of “owners” of the corporation, and managers are not shareholders’ “agents.”

As other scholars and commentators have noted, the idea that shareholders own the corporation is at best confusing and at worst incorrect. From a legal perspective, shareholders are beneficiaries of the corporation’s activities, but they do not have “dominion” over a piece of property. Nor do they enjoy access to the corporate premises or use of the corporation’s assets. What shareholders do own is their shares. That generally gives them various rights and privileges, including the right to sell their shares and to vote on certain matters, such as the election of directors, amendments to the corporate charter, and the sale of substantially all the corporation’s assets.

Furthermore, under the law in Delaware—legal home to more than half the Fortune 500 and the benchmark for corporate law—the right to manage the business and affairs of the corporation is vested in a board of directors elected by the shareholders; the board delegates that authority to corporate managers.

Within this legal framework, managers and directors are fiduciaries rather than agents—and not just for shareholders but also for the corporation. The difference is important. Agents are obliged to carry out the wishes of a principal, whereas a fiduciary’s obligation is to exercise independent judgment on behalf of a beneficiary. Put differently, an agent is an order taker, whereas a fiduciary is expected to make discretionary decisions. Legally, directors have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of the corporation, which is very different from simply doing the bidding of shareholders.

2. The theory is out of step with ordinary usage: Shareholders are not owners of the corporation in any traditional sense of the term, nor do they have owners’ traditional incentives to exercise care in managing it.

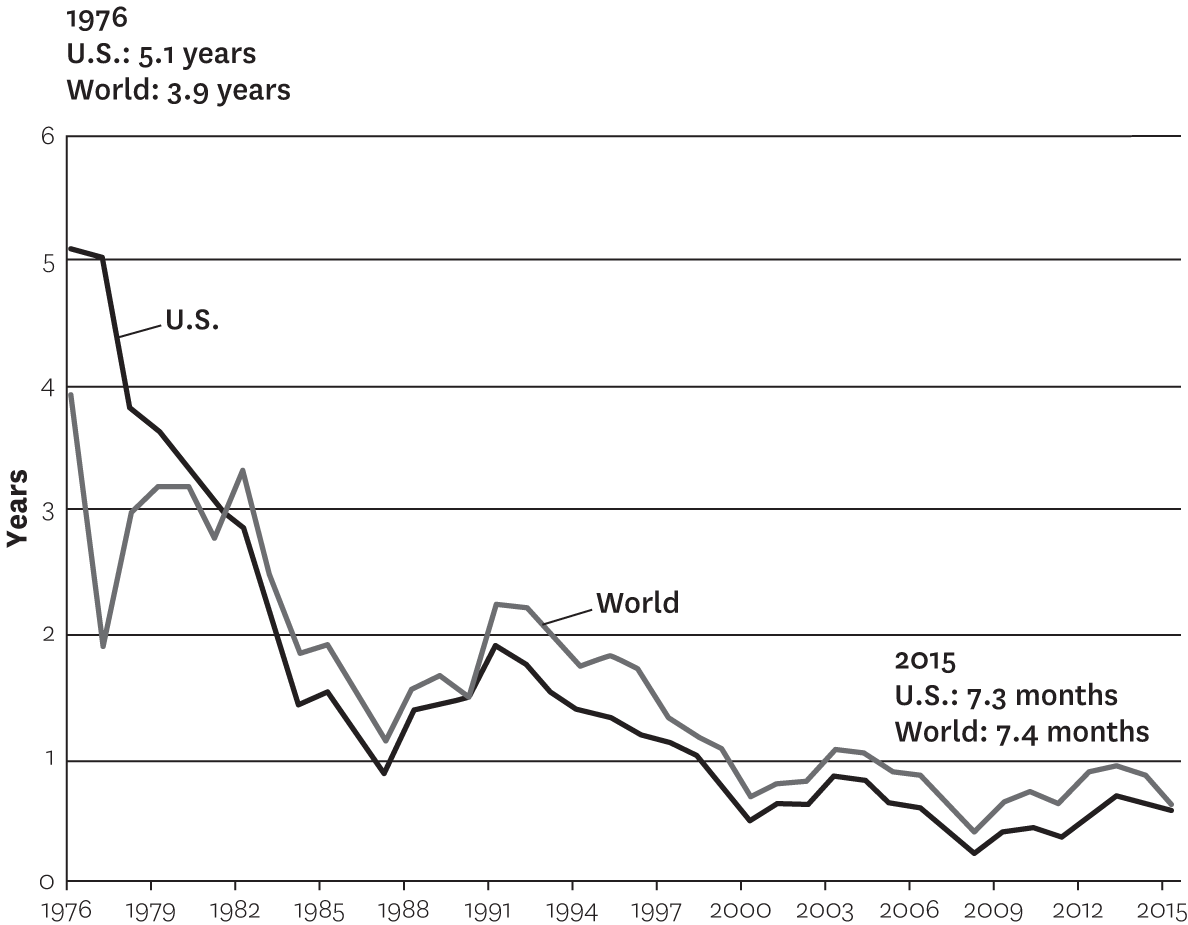

This observation is even truer today than when it was famously made by Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means in their landmark 1932 study The Modern Corporation and Private Property. Some 70% of shares in U.S.-listed companies today are held by mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign funds, and other institutional investors, which manage them on behalf of beneficiaries such as households, pensioners, policy holders, and governments. In many instances the beneficiaries are anonymous to the company whose shares the institutions hold. The professionals who manage these investments are typically judged and rewarded each quarter on the basis of returns from the total basket of investments managed. A consequence is high turnover in shares (seen in the exhibit “Average holding period for public company shares”), which also results from high-frequency trading by speculators.

Average holding period for public company shares

Source: The World Bank, World Federation of Exchanges Database.

The decisions of asset managers and speculators arise from expectations regarding share price over a relatively short period of time. As the economy passes through cycles, the shares of companies in entire industry sectors move in and out of favor. Although the shareholders of record at any given moment may vote on an issue brought before them, they need not know or care about the company whose shares they hold. Moreover, the fact that they can hedge or immediately sell their shares and avoid exposure to the longer-term effects of that vote makes it difficult to regard them as proprietors of the company in any customary sense.

The anonymity afforded the shares’ beneficial owners further attenuates their relationship to the companies whose shares they own. Some 85% of publicly traded shares in the United States are held in the name of an institution serving as an intermediary—the so-called street name—on behalf of itself or its customers. And of the ultimate owners of those shares, an estimated 75% have instructed their intermediaries not to divulge their identities to the issuing company.

3. The theory is rife with moral hazard: Shareholders are not accountable as owners for the company’s activities, nor do they have the responsibilities that officers and directors do to protect the company’s interests.

The problem with treating shareholders as proprietors is exacerbated by the absence of another traditional feature of ownership: responsibility for the property owned and accountability—even legal liability, in some cases—for injuries to third parties resulting from how that property is used. Shareholders bear no such responsibility. Under the doctrine of limited liability, they cannot be held personally liable for the corporation’s debts or for corporate acts and omissions that result in injury to others.

With a few exceptions, shareholders are entitled to act entirely in their own interest within the bounds of the securities laws. Unlike directors, who are expected to refrain from self-dealing, they are free to act on both sides of a transaction in which they have an interest. Consider the contest between Allergan and Valeant. A member of Allergan’s board who held shares in Valeant would have been expected to refrain from voting on the deal or promoting Valeant’s bid. But Allergan shareholders with a stake in both companies were free to buy, sell, and vote as they saw fit, with no obligation to act in the best interests of either company. Institutional investors holding shares in thousands of companies regularly act on deals in which they have significant interests on both sides.

In a well-ordered economy, rights and responsibilities go together. Giving shareholders the rights of ownership while exempting them from the responsibilities opens the door to opportunism, overreach, and misuse of corporate assets. The risk is less worrying when shareholders do not seek to influence major corporate decisions, but it is acute when they do. The problem is clearest when temporary holders of large blocks of shares intervene to reconstitute a company’s board, change its management, or restructure its finances in an effort to drive up its share price, only to sell out and move on to another target without ever having to answer for their intervention’s impact on the company or other parties.

4. The theory’s doctrine of alignment spreads moral hazard throughout a company and narrows management’s field of vision.

Just as freedom from accountability has a tendency to make shareholders indifferent to broader and longer-term considerations, so agency theory’s recommended alignment between managers’ interests and those of shareholders can skew the perspective of the entire organization. When the interests of successive layers of management are “aligned” in this manner, the corporation may become so biased toward the narrow interests of its current shareholders that it fails to meet the requirements of its customers or other constituencies. In extreme cases it may tilt so far that it can no longer function effectively. The story of Enron’s collapse reveals how thoroughly the body of a company can be infected.

The notion that managing for the good of the company is the same as managing for the good of the stock is best understood as a theoretical conceit necessitated by the mathematical models that many economists favor. In practical terms there is (or can be) a stark difference. Once Allergan’s management shifted its focus from sustaining long-term growth to getting the company’s stock price to $180 a share—the target at which institutional investors were willing to hold their shares—its priorities changed accordingly. Research was cut, investments were eliminated, and employees were dismissed.

5. The theory’s assumption of shareholder uniformity is contrary to fact: Shareholders do not all have the same objectives and cannot be treated as a single “owner.”

Agency theory assumes that all shareholders want the company to be run in a way that maximizes their own economic return. This simplifying assumption is useful for certain purposes, but it masks important differences. Shareholders have differing investment objectives, attitudes toward risk, and time horizons. Pension funds may seek current income and preservation of capital. Endowments may seek long-term growth. Young investors may accept considerably more risk than their elders will tolerate. Proxy voting records indicate that shareholders are divided on many of the resolutions put before them. They may also view strategic opportunities differently. In the months after Valeant announced its bid, Allergan officials met with a broad swath of institutional investors. According to Allergan’s lead independent director, Michael Gallagher, “The diversity of opinion was as wide as could possibly be”—from those who opposed the deal and absolutely did not want Valeant shares (the offer included both stock and cash) to those who saw it as the opportunity of a lifetime and could not understand why Allergan did not sit down with Valeant immediately.

The Agency-Based Model in Practice

Despite these problems, agency theory has attracted a wide following. Its tenets have provided the intellectual rationale for a variety of changes in practice that, taken together, have enhanced the power of shareholders and given rise to a model of governance and management that is unrelenting in its shareholder centricity. Here are just a few of the arenas in which the theory’s influence can be seen:

Executive compensation

Agency theory ideas were instrumental in the shift from a largely cash-based system to one that relies predominantly on equity. Proponents of the shift argued that equity-based pay would better align the interests of executives with those of shareholders. The same argument was used to garner support for linking pay more closely to stock performance and for tax incentives to encourage such “pay for performance” arrangements. Following this logic, Congress adopted legislation in 1992 making executive pay above $1 million deductible only if it is “performance based.” Today some 62% of executive pay is in the form of equity, compared with 19% in 1980.

Disclosure of executive pay

Agency theory’s definition of performance and its doctrine of alignment undergird rules proposed by the SEC in 2015 requiring companies to expand the information on executive pay and shareholder returns provided in their annual proxy statements. The proposed rules call for companies to report their annual total shareholder return (TSR) over time, along with annual TSR figures for their peer group, and to describe the relationships between their TSR and their executive compensation and between their TSR and the TSR of their peers.

Shareholders’ rights

The idea that shareholders are owners has been central to the push to give them more say in the nomination and election of directors and to make it easier for them to call a special meeting, act by written consent, or remove a director. Data from FactSet and other sources indicates that the proportion of S&P 500 companies with majority voting for directors increased from about 16% in 2006 to 88% in 2015; the proportion with special meeting provisions rose from 41% in 2002 to 61% in 2015; and the proportion giving shareholders proxy access rights increased from less than half a percent in 2013 to some 39% by mid-2016.

The power of boards

Agency thinking has also propelled efforts to eliminate staggered boards in favor of annual election for all directors and to eliminate “poison pills” that would enable boards to slow down or prevent “owners” from voting on a premium offer for the company. From 2002 to 2015, the share of S&P 500 companies with staggered boards dropped from 61% to 10%, and the share with a standing poison pill fell from 60% to 4%. (Companies without a standing pill may still adopt a pill in response to an unsolicited offer—as was done by the Allergan board in response to Valeant’s bid.)

Management attitudes

Agency theory’s conception of management responsibility has been widely adopted. In 1997 the Business Roundtable issued a statement declaring that “the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation’s stockholders” and that “the principal objective of a business enterprise is to generate economic returns to its owners.” Issued in response to pressure from institutional investors, the statement in effect revised the Roundtable’s earlier position that “the shareholder must receive a good return but the legitimate concerns of other constituencies also must have the appropriate attention.” Various studies suggest ways in which managers have become more responsive to shareholders. Research indicates, for instance, that companies with majority (rather than plurality) voting for directors are more apt to adopt shareholder proposals that garner majority support, and that many chief financial officers are willing to forgo investments in projects expected to be profitable in the longer term in order to meet analysts’ quarterly earnings estimates. According to surveys by the Aspen Institute, many business school graduates regard maximizing shareholder value as their top responsibility.

Investor behavior

Agency theory ideas have facilitated a rise in investor activism and legitimized the playbook of hedge funds that mobilize capital for the express purpose of buying company shares and using their position as “owners” to effect changes aimed at creating shareholder value. (The sidebar “The Activist’s Playbook” illustrates how agency theory ideas have been put into practice.) These investors are intervening more frequently and reshaping how companies allocate resources. In the process they are reshaping the strategic context in which all companies and their boards make decisions.

Taken individually, a change such as majority voting for directors may have merit. As a group, however, these changes have helped create an environment in which managers are under increasing pressure to deliver short-term financial results, and boards are being urged to “think like activists.”

Implications for Companies

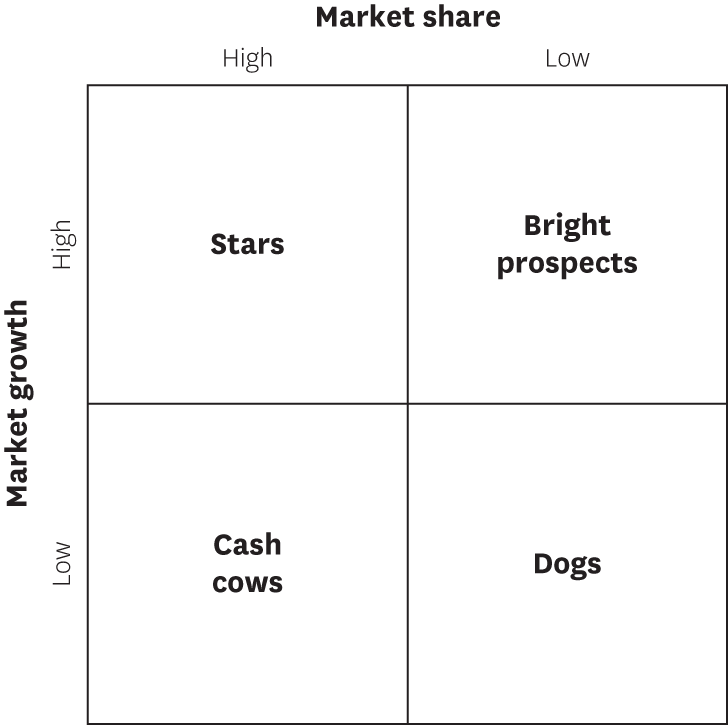

To appreciate the strategic implications of a typical activist program, it is instructive to use a tool developed in the 1960s by the Boston Consulting Group to guide the resource-allocation process. Called the growth share matrix, the tool helped managers see their company as a portfolio of businesses with differing characteristics. One group of businesses might be mature and require investment only for purposes of modest expansion and incremental improvement. Assuming they have strong market share relative to their nearest competitors, those businesses are likely to be profitable and generate cash. Another group might also have leading positions but be in fast-growing markets; they, too, are profitable, but they require heavy investment to maintain or improve market share. A third group might have weak competitive positions in mature markets; these businesses require cash for survival but have no prospects for growth or increased profits. A final group might be in rapidly growing new markets where several companies are competitive and prospects are bright but risky.

The developers of the matrix called these four groups cash cows, stars, dogs, and bright prospects, respectively. The segmentation was meant to ensure that cash cows were maintained, stars fully funded, dogs pruned, and a limited number of bright prospects chosen for their longer-term potential to become stars. (See the exhibit “The growth share matrix.”) When companies don’t manage a portfolio in this holistic fashion, funds tend to get spread evenly across businesses on the basis of individual projects’ forecasted returns.

The growth share matrix

BCG’s growth share matrix enables companies to manage a portfolio of businesses: “cash cows,” mature businesses that throw off cash; fast-growing “stars”; businesses with a weak position and few prospects for growth (“dogs”); and risky but big-upside businesses in fast-growing markets (“bright prospects”).

Source: Boston Consulting Group.

It’s a simple tool—but using it well is not simple at all. Managing a cash cow so that it remains healthy, nurturing star businesses in the face of emerging competition, fixing or divesting unpromising businesses, and selecting one or two bright prospects to grow—all this takes talented executives who can function effectively as a team. Companies that succeed in managing this ongoing resource-allocation challenge can grow and reinvent themselves continually over time.

The growth share matrix illuminates the strategic choices managers face as they seek to create value indefinitely into the future. It’s also useful for showing how to drive up a company’s share price in the short term. Suppose a corporation were to sell off the dogs, defund the bright prospects, and cut expenses such as marketing and R&D from the stars. That’s a recipe for dramatically increased earnings, which would, in turn, drive up the share price. But the corporation might lose bright prospects that could have been developed into the stars and cash cows of the future.

The activist investor Nelson Peltz’s 2014 proposal for DuPont provides an example of this idea. At the core of his three-year plan for increasing returns to shareholders was splitting the company into three autonomous businesses and eliminating its central research function. One of the new companies, “GrowthCo,” was to consist of DuPont’s agriculture, nutrition and health, and industrial biosciences businesses. A second, “CyclicalCo/CashCo,” was to include the low-growth but highly cash-generative performance materials, safety, and electronics businesses. The third was the performance chemicals unit, Chemours, which DuPont had already decided to spin off. In growth-share-matrix terms, Peltz’s plan was, in essence, to break up DuPont into a cash cow, a star, and a dog—and to eliminate some number of the bright prospects that might have been developed from innovations produced by centralized research. Peltz also proposed cutting other “excess” costs, adding debt, adopting a more shareholder-friendly policy for distributing cash from CyclicalCo/CashCo, prioritizing high returns on invested capital for initiatives at GrowthCo, and introducing more shareholder-friendly governance, including tighter alignment between executive compensation and returns to shareholders. The plan would effectively dismantle DuPont and cap its future in return for an anticipated doubling in share price.

Value Creation or Value Transfer?

The question of whether shareholders benefit from such activism beyond an initial bump in stock price is likely to remain unresolved, given the methodological problems plaguing studies on the subject. No doubt in some cases activists have played a useful role in waking up a sleepy board or driving a long-overdue change in strategy or management. However, it is important to note that much of what activists call value creation is more accurately described as value transfer. When cash is paid out to shareholders rather than used to fund research, launch new ventures, or grow existing businesses, value has not been created. Nothing has been created. Rather, cash that would have been invested to generate future returns is simply being paid out to current shareholders. The lag time between when such decisions are taken and when their effect on earnings is evident exceeds the time frames of standard financial models, so the potential for damage to the company and future shareholders, not to mention society more broadly, can easily go unnoticed.

Given how long it takes to see the fruits of any significant research effort (Apple’s latest iPhone chip was eight years in the making), the risk to research and innovation from activists who force deep cuts to drive up the share price and then sell out before the pipeline dries up is obvious. It doesn’t help that financial models and capital markets are notoriously poor at valuing innovation. After Allergan was put into play by the offer from Valeant and Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management, the company’s share price rose by 30% as other hedge funds bought the stock. Some institutions sold to reap the immediate gain, and Allergan’s management was soon facing pressure from the remaining institutions to accelerate cash flow and “bring earnings forward.” In an attempt to hold on to those shareholders, the company made deeper cuts in the workforce than previously planned and curtailed early-stage research programs. Academic studies have found that a significant proportion of hedge fund interventions involve large increases in leverage and large decreases in investment, particularly in research and development.

The activists’ claim of value creation is further clouded by indications that some of the value purportedly created for shareholders is actually value transferred from other parties or from the general public. Large-sample research on this question is limited, but one study suggests that the positive abnormal returns associated with the announcement of a hedge fund intervention are, in part, a transfer of wealth from workers to shareholders. The study found that workers’ hours decreased and their wages stagnated in the three years after an intervention. Other studies have found that some of the gains for shareholders come at the expense of bondholders. Still other academic work links aggressive pay-for-stock-performance arrangements to various misdeeds involving harm to consumers, damage to the environment, and irregularities in accounting and financial reporting.

We are not aware of any studies that examine the total impact of hedge fund interventions on all stakeholders or society at large. Still, it appears self-evident that shareholders’ gains are sometimes simply transfers from the public purse, such as when management improves earnings by shifting a company’s tax domicile to a lower-tax jurisdiction—a move often favored by activists, and one of Valeant’s proposals for Allergan. Similarly, budget cuts that eliminate exploratory research aimed at addressing some of society’s most vexing challenges may enhance current earnings but at a cost to society as well as to the company’s prospects for the future.

Hedge fund activism points to some of the risks inherent in giving too much power to unaccountable “owners.” As our analysis of agency theory’s premises suggests, the problem of moral hazard is real—and the consequences are serious. Yet practitioners continue to embrace the theory’s doctrines; regulators continue to embed them in policy; boards and managers are under increasing pressure to deliver short-term returns; and legal experts forecast that the trend toward greater shareholder empowerment will persist. To us, the prospect that public companies will be run even more strictly according to the agency-based model is alarming. Rigid adherence to the model by companies uniformly across the economy could easily result in even more pressure for current earnings, less investment in R&D and in people, fewer transformational strategies and innovative business models, and further wealth flowing to sophisticated investors at the expense of ordinary investors and everyone else.

Toward a Company-Centered Model

A better model, we submit, would have at its core the health of the enterprise rather than near-term returns to its shareholders. Such a model would start by recognizing that corporations are independent entities endowed by law with the potential for indefinite life. With the right leadership, they can be managed to serve markets and society over long periods of time. Agency theory largely ignores these distinctive and socially valuable features of the corporation, and the associated challenges of managing for the long term, on the grounds that corporations are “legal fictions.” In their seminal 1976 article, Jensen and Meckling warn against “falling into the trap” of asking what a company’s objective should be or whether the company has a social responsibility. Such questions, they argue, mistakenly imply that a corporation is an “individual” rather than merely a convenient legal construct. In a similar vein, Friedman asserts that it cannot have responsibilities because it is an “artificial person.”

In fact, of course, corporations are legal constructs, but that in no way makes them artificial. They are economic and social organisms whose creation is authorized by governments to accomplish objectives that cannot be achieved by more-limited organizational forms such as partnerships and proprietorships. Their nearly 400-year history of development speaks to the important role they play in society. Originally a corporation’s objectives were set in its charter—build and operate a canal, for example—but eventually the form became generic so that corporations could be used to accomplish a wide variety of objectives chosen by their management and governing bodies. As their scale and scope grew, so did their power. The choices made by corporate decision makers today can transform societies and touch the lives of millions, if not billions, of people across the globe.

The model we envision would acknowledge the realities of managing these organizations over time and would be responsive to the needs of all shareholders—not just those who are most vocal at a given moment. Here we offer eight propositions that together provide a radically different and, we believe, more realistic foundation for corporate governance and shareholder engagement.

1. Corporations are complex organizations whose effective functioning depends on talented leaders and managers.

The success of a leader has more to do with intrinsic motivation, skills, capabilities, and character than with whether his or her pay is tied to shareholder returns. If leaders are poorly equipped for the job, giving them more “skin in the game” will not improve the situation and may even make it worse. (Part of the problem with equity-based pay is that it conflates executive skill and luck.) The challenges of corporate leadership—crafting strategy, building a strong organization, developing and motivating talented executives, and allocating resources among the corporation’s various businesses for present and future returns—are significant. In focusing on incentives as the key to ensuring effective leadership, agency theory diminishes these challenges and the importance of developing individuals who can meet them.

2. Corporations can prosper over the long term only if they’re able to learn, adapt, and regularly transform themselves.

In some industries today, companies may need reinvention every five years to keep up with changes in markets, competition, or technology. Changes of this sort, already difficult, are made more so by the idea that management is about assigning individuals fixed decision rights, giving them clear goals, offering them incentives to achieve those goals, and then paying them (or not) depending on whether the goals are met. This approach presupposes a degree of predictability, hierarchy, and task independence that is rare in today’s organizations. Most tasks involve cooperation across organizational lines, making it difficult to establish clear links between individual contributions and specific outcomes.

3. Corporations perform many functions in society.

One of them is providing investment opportunities and generating wealth, but corporations also produce goods and services, provide employment, develop technologies, pay taxes, and make other contributions to the communities in which they operate. Singling out any one of these as “the purpose of the corporation” may say more about the commentator than about the corporation. Agency economists, it seems, gravitate toward maximizing shareholder wealth as the central purpose. Marketers tend to favor serving customers. Engineers lean toward innovation and excellence in product performance. From a societal perspective, the most important feature of the corporation may be that it performs all these functions simultaneously over time. As a historical matter, the original purpose of the corporation—reflected in debates about limited liability and general incorporation statutes—was to facilitate economic growth by enabling projects that required large-scale, long-term investment.

4. Corporations have differing objectives and differing strategies for achieving them.

The purpose of the (generic) corporation from a societal perspective is not the same as the purpose of a (particular) corporation as seen by its founders, managers, or governing authorities. Just as the purposes and strategies of individual companies vary widely, so must their performance measures. Moreover, companies’ strategies are almost always in transition as markets change. An overemphasis on TSR for assessing and comparing corporate performance can distort the allocation of resources and undermine a company’s ability to deliver on its chosen strategy.

5. Corporations must create value for multiple constituencies.

In a free market system, companies succeed only if customers want their products, employees want to work for them, suppliers want them as partners, shareholders want to buy their stock, and communities want their presence. Figuring out how to maintain these relationships and deciding when trade-offs are necessary among the interests of these various groups are central challenges of corporate leadership. Agency theory’s implied decision rule—that managers should always maximize value for shareholders—oversimplifies this challenge and leads eventually to systematic underinvestment in other important relationships.

6. Corporations must have ethical standards to guide interactions with all their constituencies, including shareholders and society at large.

Adherence to these standards, which go beyond forbearance from fraud and collusion, is essential for earning the trust companies need to function effectively over time. Agency theory’s ambivalence regarding corporate ethics can set companies up for destructive and even criminal behavior—which generates a need for the costly regulations that agency theory proponents are quick to decry.

7. Corporations are embedded in a political and socioeconomic system whose health is vital to their sustainability.

Elsewhere we have written about the damaging and often self-destructive consequences of companies’ indifference to negative externalities produced by their activities. We have also found that societal and systemwide problems can be a source of both risk and opportunity for companies. Consider Ecomagination, the business GE built around environmental challenges, or China Mobile’s rural communications strategy, which helped narrow the digital divide between China’s urban and rural populations and fueled the company’s growth for nearly half a decade. Agency theory’s insistence that corporations (because they are legal fictions) cannot have social responsibilities and that societal problems are beyond the purview of business (and should be left to governments) results in a narrowness of vision that prevents corporate leaders from seeing, let alone acting on, many risks and opportunities.

8. The interests of the corporation are distinct from the interests of any particular shareholder or constituency group.

As early as 1610, the directors of the Dutch East India Company recognized that shareholders with a 10-year time horizon would be unenthusiastic about the company’s investing resources in longer-term projects that were likely to pay off only in the second of two 10-year periods allowed by the original charter. The solution, suggested one official, was to focus not on the initial 10-year investors but on the strategic goals of the enterprise, which in this case meant investing in those longer-term projects to maintain the company’s position in Asia. The notion that all shareholders have the same interests and that those interests are the same as the corporation’s masks such fundamental differences. It also provides intellectual cover for powerful shareholders who seek to divert the corporation to their own purposes while claiming to act on behalf of all shareholders.

These propositions underscore the need for an approach to governance that takes the corporation seriously as an institution in society and centers on the sustained performance of the enterprise. They also point to a stronger role for boards and a system of accountability for boards and executives that includes but is broader than accountability to shareholders. In the model implied by these propositions, boards and business leaders would take a fundamentally different approach to such basic tasks as strategy development, resource allocation, performance evaluation, and shareholder engagement. For instance, managers would be expected to take a longer view in formulating strategy and allocating resources.

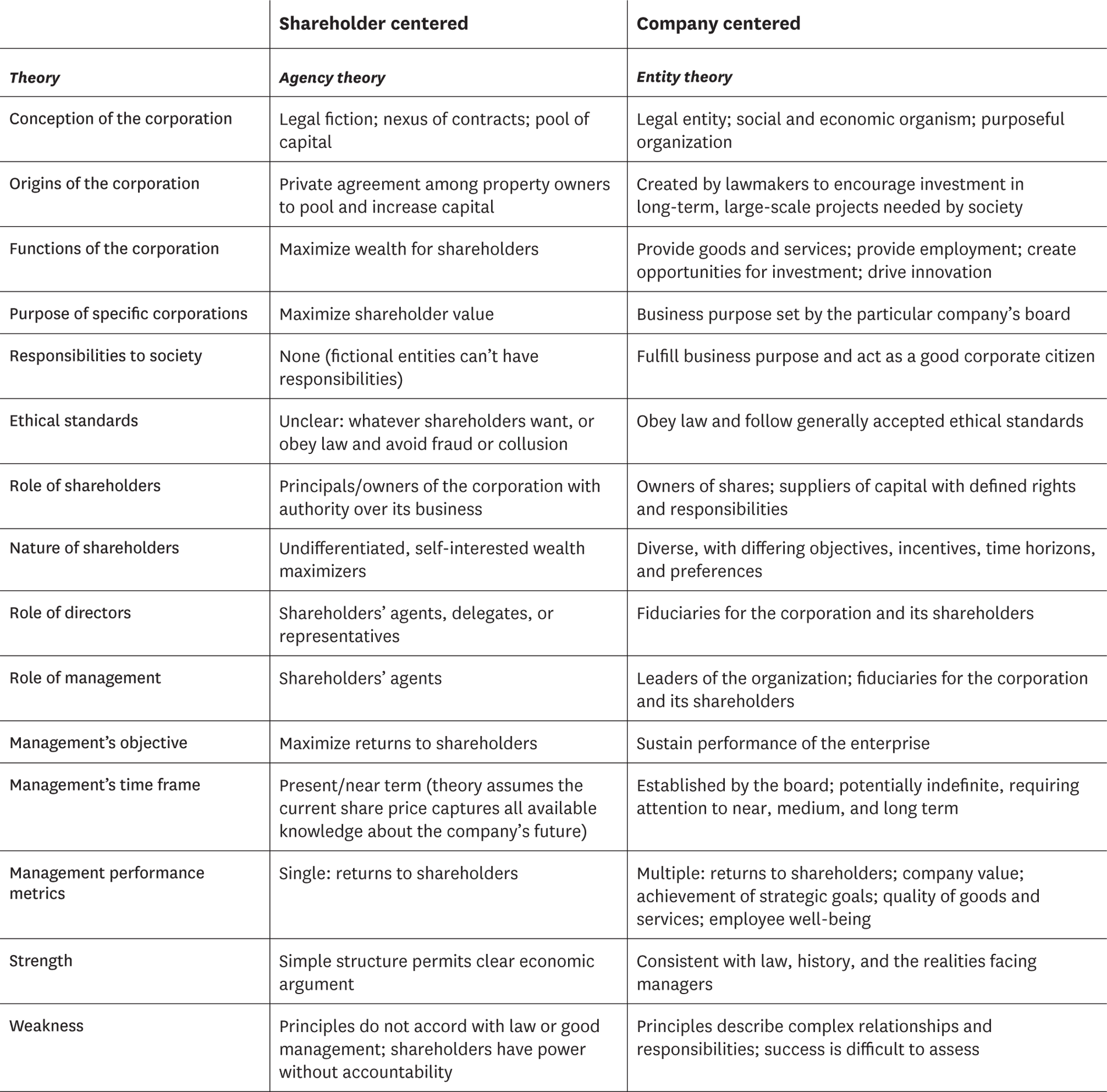

The new model has yet to be fully developed, but its conceptual foundations can be outlined. As shown in the exhibit “Contrasting approaches to corporate governance,” the company-centered model we envision tracks basic corporate law in holding that a corporation is an independent entity, that management’s authority comes from the corporation’s governing body and ultimately from the law, and that managers are fiduciaries (rather than agents) and are thus obliged to act in the best interests of the corporation and its shareholders (which is not the same as carrying out the wishes of even a majority of shareholders). This model recognizes the diversity of shareholders’ goals and the varied roles played by corporations in society. We believe that it aligns better than the agency-based model does with the realities of managing a corporation for success over time and is thus more consistent with corporations’ original purpose and unique potential as vehicles for projects involving large-scale, long-term investment.

The practical implications of company-centered governance are far-reaching. In boardrooms adopting this approach, we would expect to see some or all of these features:

greater likelihood of a staggered board to facilitate continuity and the transfer of institutional knowledge

more board-level attention to succession planning and leadership development

more board time devoted to strategies for the company’s continuing growth and renewal

closer links between executive compensation and achieving the company’s strategic goals

more attention to risk analysis and political and environmental uncertainty

a strategic (rather than narrowly financial) approach to resource allocation

a stronger focus on investments in new capabilities and innovation

more-conservative use of leverage as a cushion against market volatility

concern with corporate citizenship and ethical issues that goes beyond legal compliance

A company-centered model of governance would not relieve corporations of the need to provide a return over time that reflected the cost of capital. But they would be open to a wider range of strategic positions and time horizons and would more easily attract investors who shared their goals. Speculators will always seek to exploit changes in share price—but it’s not inevitable that they will color all corporate governance. It’s just that agency theory, in combination with other doctrines of modern economics, has erased the distinctions among investors and converted all of us into speculators.

If our model were accepted, speculators would have less opportunity to profit by transforming long-term players into sources of higher earnings and share prices in the short term. The legitimizing argument for attacks by unaccountable parties with opaque holdings would lose its force. We can even imagine a new breed of investors and asset managers who would focus explicitly on long-term investing. They might develop new valuation models that take a broader view of companies’ prospects or make a specialty of valuing the hard-to-value innovations and intangibles—and also the costly externalities—that are often ignored in today’s models. They might want to hold shares in companies that promise a solid and continuing return and that behave as decent corporate citizens. Proxy advisers might emerge to serve such investors.

We would also expect to find more support for measures to enhance shareholders’ accountability. For instance, activist shareholders seeking significant influence or control might be treated as fiduciaries for the corporation or restricted in their ability to sell or hedge the value of their shares. Regulators might be inclined to call for greater transparency regarding the beneficial ownership of shares. In particular, activist funds might be required to disclose the identities of their investors and to provide additional information about the nature of their own governance. Regulators might close the 10-day window currently afforded between the time a hedge fund acquires a disclosable stake and the time the holding must actually be disclosed. To date, efforts to close the window have met resistance from agency theory proponents who argue that it is needed to give hedge funds sufficient incentive to engage in costly efforts to dislodge poorly performing managers.

The time has come to challenge the agency-based model of corporate governance. Its mantra of maximizing shareholder value is distracting companies and their leaders from the innovation, strategic renewal, and investment in the future that require their attention. History has shown that with enlightened management and sensible regulation, companies can play a useful role in helping society adapt to constant change. But that can happen only if directors and managers have sufficient discretion to take a longer, broader view of the company and its business. As long as they face the prospect of a surprise attack by unaccountable “owners,” today’s business leaders have little choice but to focus on the here and now.

Originally published in May–June 2017. Reprint R1703B

The CEO View: Defending a Good Company from Bad Investors

A conversation with former Allergan CEO David Pyott by Sarah Cliffe

David Pyott had been the CEO of Allergan for nearly 17 years in April 2014, when Valeant Pharmaceuticals and Pershing Square Capital Management initiated the hostile takeover bid described in the accompanying article “The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership.” He was the company’s sole representative during the takeover discussions. When it became clear that the bid could not be fended off indefinitely, Pyott, with his board’s blessing, negotiated a deal whereby Allergan would be acquired by Actavis (a company whose business model, like Allergan’s, was growth oriented).

HBR: Would you describe Allergan’s trajectory in the years leading up to the takeover bid?

Pyott: We’d experienced huge growth since 1998, when I joined as just the third CEO of Allergan and the first outsider in that role. We restructured when I came in and again 10 years later, during the recession. Those cuts gave us some firepower for investing back into the economic recovery. After the recession we were telling the market to expect double-digit growth in sales revenue and around the mid-teens in earnings per share.

Your investor relations must have been excellent.

They were. I am extremely proud to say that we literally never missed our numbers, not once in 17 years. We also won lots of awards from investor-relations magazines. You don’t run a business with that in mind, but it’s nice to be recognized.

In their article, Joseph Bower and Lynn Paine describe how difficult it is for any company to manage the pressure from investors who want higher short-term returns. You seem to have managed that well—until Valeant showed up. How?

Both buy-side and sell-side investors are like any other customer group. You should listen to what they say and respond when you can. But remember: Asking is free. If they say, “Hey, we want more,” you have to be willing to come back with “This is what we can commit to. If there are better places to invest your funds, then do what you need to.” Fortunately or unfortunately, I’m very stubborn.

Permit me a naive question: Since Allergan was going strong, why did it make sense to Valeant/Pershing Square to take you over and strip you down? I get that they’d make a lot of money, but wouldn’t fostering continued growth make more in the long run?

Different business models. Valeant was a roll-up company; it wasn’t interested in organic growth. Michael Pearson [Valeant’s CEO] liked our assets—and he needed to keep feeding the beast. If he didn’t keep on buying the next target, then the fact that he was stripping all the assets out of companies he’d already bought would have become painfully obvious.

He couldn’t do it alone, given his already weak balance sheet, so he brought Ackman in—and Pershing Square acquired 9.7% of our stock without our knowledge. This was meant to act as a catalyst to create a “wolf pack.” Once the hedge funds and arbitrageurs get too big a position, you lose control of your company.

I still thought we had a strong story to tell—and I hoped I could get long-term-oriented shareholders to buy new stock and water down the hedge funds’ holdings. But almost nobody was willing to up their position. They all had different reasons—some perfectly good ones. It was a lesson to me.

That must have been disappointing.

Yes. It’s poignant—some of those same people say to me now, “We miss the old Allergan. We’re looking for high-growth, high-innovation stocks and not finding them.” I just say, “I heartily agree with you.”

Another thing that surprised and disappointed me was that I couldn’t get people who supported what we were doing— who understood why we were not accepting the bid, which grossly undervalued the company—to talk to the press. Several people said they would, but then folks at the top of their companies said no. And the reporters who cover M&A don’t know the companies well. The people who cover pharma are deeply knowledgeable—but once a company is in play, those guys are off the story day-to-day. So the coverage was more one-sided than we’d have hoped for.

Is the trend toward activist investors something that the market will eventually sort out?

Activist and hostile campaigns have been propelled by extraordinarily low interest rates and banks’ willingness to accept very high leverage ratios. Recently investor focus has returned to good old-fashioned operational execution by management. But I do think that investment styles go in and out of fashion. I never would have guessed that when I went to business school.

Do you agree with Bower and Paine that boards and CEOs need to focus less on shareholder wealth and more on the well-being of the company?

Look at it from a societal point of view: A lot of the unrest we’ve seen over the past year is rooted in the idea that wealthy, powerful people are disproportionately benefiting from the changes happening in society. A lot of companies think that they need to make themselves look more friendly, not just to stockholders but to employees and to society. Having a broader purpose—something beyond simply making money—is how you do that and how you create strong corporate cultures.

I don’t believe that strong performance and purpose are at odds, not at all. My own experience tells me that in order for a company to be a really high performer, it needs to have a purpose. Money matters to employees up to a point, but they want to believe they’re working on something that improves people’s lives. I’ve also found that employees respond really favorably when management commits to responsible social behavior. I used to joke with employees about saving water and energy and about recycling: “Look, I’m Scottish, OK? I don’t like waste, and it saves the company money.” That’s a positive for employees.

Did that sense of purpose pay off when you were going through the takeover bid?

Absolutely. I left day-to-day operations to our president, Doug Ingram, that year. And we grew the top line 17%—more than $1 billion—the best operating year in our 62-year history. I remember an R&D team leader who came up to me in the parking lot and said, “Are you OK? Is there anything I can do?” I answered him, “Just do your job better than ever, and don’t be distracted by the rubbish you read in the media.” Employees all over the world outdid themselves, because they believed in the company.

What changes in government rules and regulations would improve outcomes for the full range of stakeholders?

My favorite fix is changing the tax rates. Thirty-five percent is woefully high relative to the rest of the world. If we got it down to 20%, we’d be amazed at how much investment and job creation happened in this country. The high rates mean that we’re vulnerable to takeovers that have tax inversion as a motivator. We were paying 26%, and Valeant [headquartered in Canada] paid 3%. I think the capital gains taxes could be changed—in a revenue-neutral way—to incentivize holding on to stocks longer.

Shifting gears again: If a company wants to reorient itself toward long-term growth, what has to happen?

I think it’s hard for a CEO to change his or her spots. Some can, but most can’t. So in most cases you’re going to need a new leader. And the board of directors really has to buy into it, because not only are you changing your strategy, you’re changing your numbers. You must have a story to tell, for example: “For the next three years, we’re not going to deliver 10% EPS growth. It’s going to be 5% while we invest in the future. And that’s not going to pay off until after three years, so you’ll have to be patient.” You have to be very, very clear about it.

And then everyone—the board, the investors, the lab technicians, the salespeople—will watch you to see if you’re serious. It will take a lot of fortitude and determination. It’s not impossible, but it’s extremely difficult.

Originally published in May–June 2017. Reprint R1703B

Finally, Evidence That Managing for the Long Term Pays Off

by Dominic Barton, James Manyika, and Sarah Keohane Williamson

Companies deliver superior results when executives manage for long-term value creation and resist pressure from analysts and investors to focus excessively on meeting Wall Street’s quarterly earnings expectations. This has long seemed intuitively true to us. We’ve seen companies such as Unilever, AT&T, and Amazon succeed by sticking resolutely to a long-term view. And yet we have not had the comprehensive data needed to quantify the payoff from managing for the long term—until now.

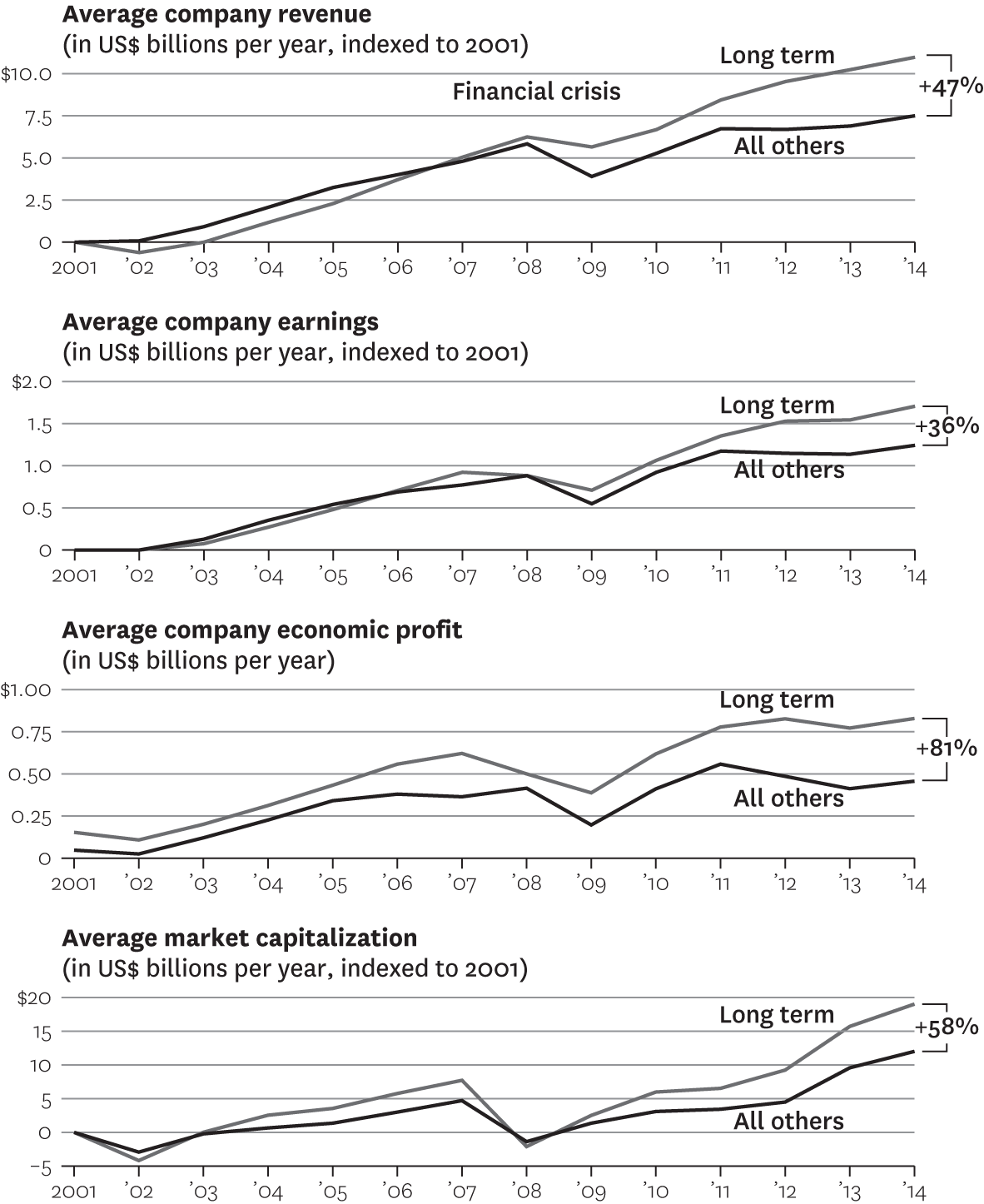

New research, led by a team from McKinsey Global Institute in cooperation with FCLT Global, found that companies that operate with a true long-term mindset have consistently outperformed their industry peers since 2001 across almost every financial measure that matters.

Firms focused on the long term exhibit stronger fundamentals and performance

Source: McKinsey Global Institute.

The differences were dramatic. Among the firms we identified as focused on the long term, average revenue and earnings growth were 47% and 36% higher, respectively, by 2014, and market capitalization grew faster as well. The returns to society and the overall economy were equally impressive. By our measures, companies that were managed for the long term added nearly 12,000 more jobs on average than their peers from 2001 to 2015. We calculate that U.S. GDP over the past decade might well have grown by an additional $1 trillion if the whole economy had performed at the level our long-term stalwarts delivered—and generated more than five million additional jobs over this period.

Who are these overachievers and how did we identify them? We’ll dive into those answers shortly. But first, it’s worth pausing to consider why finding conclusive data that establishes the rewards from long-term management has been so hard—and just how tangled the debate over this issue has been as a result.

In recent years we have learned a lot about the causes of short-termism and its intensifying power. We know from FCLT surveys, for example, that 61% of executives and directors say that they would cut discretionary spending to avoid risking an earnings miss, and a further 47% would delay starting a new project in such a situation, even if doing so led to a potential sacrifice in value. We also know that most executives feel the balance between short-term accountability and long-term success has fallen out of whack; 65% say the short-term pressure they face has increased in the past five years. We can all see what appear to be the results of excessive short-termism in the form of record levels of stock buybacks in the U.S. and historic lows in new capital investment.

But while measuring the increase in short-term pressures and identifying perverse incentives is fairly straightforward, assessing the ultimate impact of corporate short-termism on company performance and macroeconomic growth is highly complex. After all, “short-termism” does not correspond to any single quantifiable metric. It is a confluence of so many complex factors it can be nearly impossible to pin down. As a result, despite persistent calls for more long-term behavior from us and from CEOs who share our views, such as Larry Fink of BlackRock and Mark Wiseman, the former head of the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, a genuine debate has continued to rage among economists and analysts over whether short-termism really destroys value.

Academic studies have linked the possible effects of short-termism to lower investment rates among publicly traded firms and decreased returns over a multiyear time horizon. Ambitious work has even attempted to quantify economic growth foregone due to cuts in R&D expenditure driven by short-termism, putting it in the range of about 0.1% per year. Other researchers, however, remain skeptical. How, they ask, could corporate profits in the U.S. remain so high for so long if short-termism were such a drag on performance? And isn’t the focus on quarterly results a natural outgrowth of the rigorous corporate governance that keeps executives accountable?

What We Actually Measured—and the Limits of Our Knowledge

To help provide a better factual base for this debate, MGI, working with McKinsey colleagues from our Strategy & Corporate Finance practice as well as the team at FCLT Global, began last fall to devise a way to systemically measure short-termism and long-termism at the company level. It started with developing a proprietary Corporate Horizon Index. The data for this index was drawn from 615 nonfinance companies that had reported continuous results from 2001 to 2015 and whose market capitalization in that period had exceeded $5 billion in at least one year. (We wanted to focus on companies large enough to feel the potential short-term pressures exerted by shareholders, boards, activists, and others.) Collectively, our sample accounts for about 60%–65% of total U.S. public market capitalization over this period. To further ensure valid results and to avoid bias in our sample, we evaluated all companies in our index only relative to their industry peers with similar opportunity sets and market conditions and tracked them over several years. We also looked at the proportional composition of the long-term and short-term groups to ensure they are approximately equivalent, so that the differential performance of individual industries cannot bias the overall results, and conducted other tests and controls to ensure statistical robustness.

One final caveat: While we firmly believe our index enables us to classify companies as “long-term” in an unbiased manner, our findings are descriptive only. We aren’t saying that a long-term orientation causes better performance, nor have we controlled for every factor that could impact the relationship between those two. All we can say is that companies with a long-term orientation tend to perform better than similar but short-term-focused firms. Even so, the correlation we uncovered between behaviors that typify a longer-term approach and superior historical performance deliver a message that’s hard to ignore.

To construct our Corporate Horizon Index, we identified five financial indicators, selected because they matched up with five hypotheses we had developed about the ways in which long- and short-term companies might differ. These indicators and hypotheses were:

Investment. The ratio of capex to depreciation. We assume long-term companies will invest more and more-consistently than other companies.

Earnings quality. Accruals as a share of revenue. Our belief is that the earnings of long-term companies will rely less on accounting decisions and more on underlying cash flow than other companies.

Margin growth. Difference between earnings growth and revenue growth. We assume that long-term companies are less likely to grow their margins unsustainably in order to hit near-term targets.

Earnings growth. Difference between earnings-per-share (EPS) growth and true earnings growth. We hypothesize that long-term companies will focus less on things like Wall Street’s obsession with earnings-per-share, which can be influenced by actions such as share repurchases, and more on the absolute rise or fall of reported earnings.

Quarterly targeting. Incidence of beating or missing EPS targets by less than two cents. We assume long-term companies are more likely to miss earnings targets by small amounts (when they easily could have taken action to hit them) and less likely to hit earnings targets by small amounts (where doing so would divert resources from other business needs).

After running the numbers on these indicators, two broad groups emerged among those 615 large and midcap U.S. publicly listed companies: a “long-term” group of 164 companies (about 27% of the sample), which were either long-term relative to their industry peers over the entire sample or clearly became more long-term between the first half of the sample period and the second half, and a baseline group of the 451 remaining companies (about 73% of the sample). The performance gap that subsequently opened between these two groups of companies offers the most compelling evidence to date of the relative cost of short-termism—and the real payoff that arises from managing for the long term.

Trillions of Dollars of Value Creation at Stake

To recap, from 2001 to 2014, the long-term companies identified by our Corporate Horizons Index increased their revenue by 47% more than others in their industry groups and their earnings by 36% more, on average. Their revenue growth was less volatile over this period, with a standard deviation of growth of 5.6%, versus 7.6% for all other companies. Our long-term firms also appeared more willing to maintain their strategies during times of economic stress. During the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, they not only saw smaller declines in revenue and earnings but also continued to increase investments in research and development while others cut back. From 2007 to 2014, their R&D spending grew at an annualized rate of 8.5%, greater than the 3.7% rate for other companies.

Another way to measure the value creation of long-term companies is to look through the lens of what is known as “economic profit.” Economic profit represents a company’s profit after subtracting a charge for the capital that the firm has invested (working capital, fixed assets, goodwill). The capital charge equals the amount of invested capital times the opportunity cost of capital—that is, the return that shareholders expect to earn from investing in companies with similar risk. Consider, for example, Company A, which earns $100 of after-tax operating profit, has an 8% cost of capital and $800 of invested capital. In this case its capital charge is $800 times 8%, or $64. Subtracting the capital charge from profits gives $36 of economic profit. A company is creating value when its economic profit is positive, and destroying value if its economic profit is negative.

With this metric, the gap between long-term companies and the rest is even bigger. From 2001 to 2014 those managing for the long term cumulatively increased their economic profit by 63% more than the other companies. By 2014 their annual economic profit was 81% larger than their peers, a tribute to superior capital allocation that led to fundamental value creation.

No path goes straight up, of course, and the long-term companies in our sample still faced plenty of character-testing times. During the last financial crisis, for example, they saw their share prices take greater hits than their short-term counterparts. Afterward, however, the long-term firms significantly outperformed, adding an average of $7 billion more to their companies’ market capitalization from 2009 and 2014 than their short-term peers did.

While we can’t directly measure the cost of short-termism, our analysis gives an indication of just how large the value of what’s being left on the table might be. As noted earlier, if all public U.S. companies had created jobs at the scale of the long-term-focused organizations in our sample, the country would have generated at least five million more jobs from 2001 and 2015—and an additional $1 trillion in GDP growth (equivalent to an average of 0.8 percentage points of GDP growth per year). Projecting forward, if nothing changes to close the gap between the long-term group and the others, then the U.S. economy could be giving up another $3 trillion in foregone GDP and job growth by 2025. Clearly, addressing persistent short-termism should be an urgent issue not just for investors and boards but also for policy makers.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Our research is just a first step toward understanding the scope and magnitude of corporate short-termism. For instance, our initial dataset was limited to the U.S., but we know the problem is a global one. How do the costs and drivers differ by regions? Our sample set consists only of publicly listed companies. How do the effects we discovered differ among private companies or among public companies with varying types of ownership structures? Are there metrics that can help predict when a company is becoming too short-term—and how do they differ among industries? Most important, what are the interventions that will prove most effective in shifting organizations onto a more productive long-term path?

On this last point, we and many others have identified steps that executives, boards, and institutional investors can take to achieve a better balance between hitting targets in the short term and operating with a persistent long-term vision and strategy. These range from creating investment mandates that reward long-term value creation, to techniques for “de-biasing” corporate capital allocation, to rethinking traditional approaches to investor relations and board composition. We will return to HBR in coming months with more data and insights into how companies can strengthen their long-term muscles.

The key message from this research is not only that the rewards from managing for the long term are enormous; it’s also that, despite strong countervailing pressures, real change is possible. The proof lies in a small but significant subset of our long-term outperformers—14%, to be precise—that didn’t start out in that category. Initially, these companies scored on the short-term end of our index. But over the course of the 15-year period we measured, leaders at the companies in this cohort managed to shift their corporations’ behavior sufficiently to move into the long-term category. What were the practical actions these companies took? Exploring that question will be a major focus for our research in the coming year. For now, the simple fact of their success is an inspiration.

Originally published in February 2017. Reprint H03GCC