TAINO WORDS

Fewer than 200 Taino words are still known. Some crept into our language:

canoa (canoe)

hamaca (hammock)

tobacco

barbecue

maize

guava

papaya

annatto (a fruit used to color

yellow cheese)

hamaca (hammock)

tobacco

barbecue

maize

guava

papaya

annatto (a fruit used to color

yellow cheese)

“When you ask for something, they never say no. To the contrary, they offer to share with anyone.”—Christopher Columbus, describing the people he met in the New World

Guanahani and Other Islands of the New World, 1492

The naked people who stared at the pale, armor-clad Spaniards splashing toward them that morning in 1492 repeated the word “Taino,” which may have meant “We are the good people.” They were farmers and fishers who placed their small villages near fields of corn, sweet potatoes, and manioc. They had lean, olive-tan bodies, decorated with tattoos, necklaces, bracelets, and headdresses. Their weapons were sharpened sticks. While the explorers from Europe convinced themselves that they had reached Cipango—Japan—those who lived there called their island home Guanahani, which translates to “small upper waters land.”

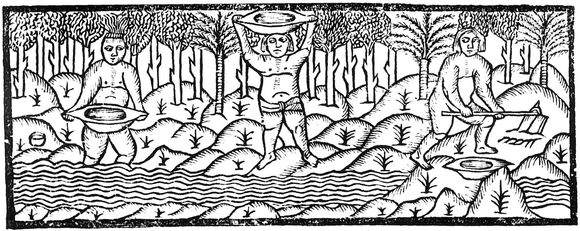

This sixteenth-century woodcut shows Taino women making cassava bread.

“All those that I saw were young people, none of whom was over thirty years old,” wrote Christopher Columbus, describing the first group of people he met in the New World. Indeed, anthropologists conclude that at least half of all Tainos were fifteen or younger.

Taino youth rolled out of their cotton hammocks at dawn and scooped breakfast from a big clay pot, still warm from last night’s meal. It was usually leftover “pepper pot” stew, made with the bitter juice of a tall, leafy plant called manioc. After breakfast, girls would go off to help their aunts, cousins, and mothers tend manioc in fields and take care of young children. They peeled and sliced sweet potatoes and rolled manioc into flour to make cassava bread. Girls helped their mothers plant maize, scratching holes into the earth with a pointed stick. Girls also took fiber from cotton and wound it into cords to make hammocks.

| THE SPANISH GAVE THE NEW WORLD: | THE TAINOS GAVE SPAIN: |

|---|---|

| bananas | chili peppers |

| the common cold | corn |

| cows | peanuts |

| ham (the first six pigs) | petunias |

| honeybees | pineapples |

| lettuce | sea island cotton |

| measles | tapioca |

| olives | tobacco (cigars that they smoked through their noses) |

| onions | |

| oranges | |

| stucco houses | |

| wheat |

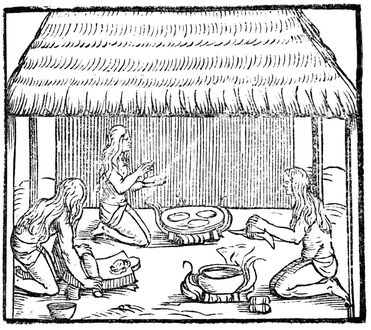

Boys hunted and fished with the men. They lowered nets from boats into the ocean, and then hauled in the catch. Sometimes they speared larger fish with bone-tipped harpoons. Tainos made huge canoes by hollowing out the trunks of trees. Some were so large they could hold fifty rowers. When everyone stroked together in rhythm, Taino canoes were faster than Spanish ships.

Taino children roamed the islands with small yellow dogs called alcos that couldn’t bark and are now extinct. Boys and girls chased down lizards, iguanas, snakes, and birds. They shinnied up trees and caught wild parrots by luring them with tame parrots tied to their hands. They snacked throughout the day, grabbing handfuls of sea grapes and coco plums, snatching birds’ eggs from nests, and peeling snails from rocks. Boys and girls practiced a ball game called batey—a cross between volleyball and soccer played with a rubber ball. Players sent the ball back and forth through the air, using all parts of their body but their hands. Teams from villages often competed with one another.

When a Taino boy reached twelve or thirteen, he went to live with his mother’s brother, who became even more important to him than his father. Taino children grew up to worship two supreme gods, one male and one female. They believed that after a person died, his or her soul would enter a paradise called coyaba, where there would be no more hurricanes or hunger or sickness and there would always be plenty of water to drink.

The Spaniards didn’t understand much of this. In his journal, Columbus described the Tainos as “people poor in everything.” He assumed they would happily believe anything the explorers told them. The Spanish were keenly interested in the small pieces of gold that dangled from Taino ears and nostrils—which, the explorers thought, proved that they had actually reached Japan. The Tainos, fearful of the Spaniards’ weapons, were eager to please. The Tainos kept saying yes, there was more gold. And there was, but not much. There were no palaces with golden roofs, just nuggets that had washed down to the bottoms of mountain streams in Hispaniola over many years.

EXPANDING THE CHURCH

“They are convinced that we come from the heavens; and they say very quickly any prayer that we tell them to say, and they make the sign of the cross … Your highnesses ought to resolve to make them Christians: for I believe that if you begin, in a short time you will end up having converted to our Holy Faith a multitude of peoples and acquiring large dominions and great riches for all of the people for Spain.”

—Columbus in a letter to Ferdinand and Isabella

TWO BOYS WHO SAW COLUMBUS’S PARADE

Columbus became a hero to the Spanish boys and girls who got to see his parade. A fourteen-year-old boy named Francisco Pizarro watched the procession pass through Sierra de Estremadura. Years later, Pizarro led the conquest of Peru for Spain, killing and enslaving many Incas who lived in the Andes Mountains. When Columbus and his captives passed through the town of Medellin, a small, delicate boy named Hernan Cortés watched in admiration. He grew up to lead the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs in Mexico.

“ARE THEY NOT HUMAN BEINGS?”

Some Spaniards tried to help the Tainos. One Sunday morning in 1511, Friar Antonio Montesinos, a Catholic priest who lived on Hispaniola, scolded the colonial leaders in a sermon. He aimed his words straight for the heart:

“I must cry out to you that we are a people in sin. You are destroying an innocent people. And for it you deserve damnation from a God of wrath. By what right do you force labor from these people in your mines and in your fields? Are they not human beings? Have they no souls, no minds? Are you not under God’s command to love them as you love yourself? In the name of all that is good and holy will you stop?”

The Spaniards grew impatient. On November 11, 1492, they captured five Taino children who paddled their canoe up alongside the Niña, perhaps to show off their parrots or trade for trinkets. Columbus wrote that he intended to take them to Spain to learn Spanish and then bring them back to help priests convert Indians to Christianity. A week later the two oldest squirmed free and dived overboard. A furious Columbus watched them splash away.

Three weeks later, a group of girls digging manioc plants in a field glanced up just in time to see eight Spanish sailors creeping up on them. They wheeled and ran for their lives. The Spaniards sprinted after them but soon pulled up gasping in their heavy armor. “The youths were too fast,” Columbus noted sourly in that day’s journal.

After three months of exploration, the Niña and the Pinta headed back to Spain with the Tainos they had finally managed to capture. At least six survived the cold, stormy voyage. Others froze or starved, and their bodies were thrown overboard.

When the survivors reached Spain, Columbus marched his Indians through the Spanish countryside, displaying them as if they were creatures from a distant star. The small parade wound hundreds of miles through dirt paths and cobbled streets to Barcelona, where the king and queen had moved the royal court. Whenever they reached a village, people hustled to the roadside to cheer the Spanish sailors and stare at their strange bounty. First in line came the barely clothed Tainos, probably cold, frightened, and confused by the attention. Many villagers reached out to touch them. Next marched the Spanish crew members, holding live parrots aloft in cages or bouncing rubber balls and showing off the golden trinkets and animal specimens they had brought back from the New World. Columbus proudly brought up the rear on horseback.

Ferdinand and Isabella were delighted with Columbus. Surely the gold trinkets meant there was more gold. The six kidnapped Tainos were baptized and given Christian names. The king and queen quickly granted Columbus much more money to return to the New World and establish a Spanish colony.

A few months later, the Tainos who gathered to watch the second group of Spanish ships arrive saw something quite different from those who had seen the first group the year before. This time the Spaniards had come to stay. Now there were seventeen sailing ships carrying twelve hundred men and boys (the first thirty women and girls did not arrive

until 1498). A parade of strange creatures spilled out of the boats into the surf: horses, mules, cows, pigs, dogs, cats, chickens, goats, and sheep. All these were new to the western hemisphere. There were sacks of wheat and seeds for garden vegetables and citrus and apple trees to cultivate. There were also cannons, muskets, armor, and attack dogs.

When the Spanish discovered that the fort at La Navidad had been destroyed and all the Spaniards who had stayed behind were dead, it was the beginning of the end for the Tainos. It didn’t matter that the Tainos had defended themselves against men who sought to enslave them and capture their women. Now the Spanish cracked down. In 1495, armed men rounded up fifteen hundred Taino men, women, and children and shipped five hundred of the healthiest-looking back to Spain as slaves. In what is now Haiti, the Spaniards ordered each Taino male over the age of fourteen to give the Spaniards enough gold dust to fill a small copper bell every three months—or be put to death. No matter how hard they worked, there wasn’t enough gold. Some Taino parents killed their children to keep them from facing a hopeless future.

Even more Tainos began to die of new diseases carried by the Spaniards, especially smallpox. When there were too few Tainos to mine gold and harvest sugarcane, Spaniards began to capture or buy slaves from Africa. Fifty years after the first Spanish men and boys appeared, there were only sixty Tainos left in all of Puerto Rico. The civilization of hammocks, silent yellow dogs, and games of batey was gone, never to return.

Sixteenth-century European view of Tainos panning for gold