“LOVE YOU NOT ME?”

“Kekaten Pokahontas patiaquagh niugh tanks manotyens mawo-kick.”

Translation: “Bid Pocahontas bring hither two little baskets and I will give her white beads to make her a chain.” It was a sentence Pocahontas taught John Smith to say when he wanted to send her a message.

“Love you not me?”—a sentence the English boys taught Pocahontas to say. They begged her to say it over and over. She in turn taught it to the girls of her tribe.

“Had it not been for Pocahontas, Virginia might lie to this day as it was on our first arrival.”—John Smith, in a letter to Queen Anne of England, 1616

Werowocomoco, 1607

Pocahontas is usually described as the brave daughter of an Indian chief, a girl who fell in love with the English adventurer John Smith and helped the British get started in the New World. It has been difficult for historians to know what she was really like, partly because most information about her comes from the writings of Smith himself. Her father, Powhatan, was a mighty ruler. He united thirty-one separate tribes into a great nation stretching from Virginia through the Carolinas. He had no use for white colonizers. Twice he drove Spanish settlers away, and his warriors may have destroyed a British attempt to start a colony in North Carolina. He didn’t welcome the three new English ships that appeared in Chesapeake Bay in 1607. In that same year Pocahontas’s carefree childhood came to an end.

The year the ships arrived, Pocahontas was eleven or twelve years old. Her real name was Matoaka, or “Little Snow Feather,” but because her tribe believed that to reveal one’s true name to outsiders gave away power, she also had a second name, Pocahontas, which meant “playful one.”

It was easy to be playful in her village, Werowocomoco, where Powhatan children were given a long time to grow up. They built scarecrow houses in the middle of their cornfields and hid inside, throwing stones out at the animals that came to nibble the crops. Boys and girls played running games, some with sticks or balls. They ran almost naked in warm weather and wrapped themselves in deerskin coats and feathered cloaks when the weather turned cold.

Pocahontas’s father was the most powerful ruler in the world they knew. Cloaked in a raccoon robe, Chief Powhatan (his real name was Wahunsonacock, but he was called Powhatan as the chief of the Powhatan nation) seated himself high above his subjects on a throne twelve mats thick. It was well known that Pocahontas was his favorite among his twenty-seven children. She often sat beside him, and he respected her insight even though she was young.

In April of 1607, news arrived that ships carrying “round-eyes,” or white-skinned men, had arrived and that they had built a small wooden fort on a peninsula near the widening of a river. Chief Powhatan was instantly suspicious. Though they were quick to clap their hands over their hearts as a sign of friendship, he suspected that these men and boys were like the whites who had come before: They would want corn and offer nothing of value in return. Barely a week after they landed, Powhatan sent a party of two hundred braves to attack Jamestown. After killing many whites, the braves were driven off by cannon fire. Those cannons interested Powhatan very much.

Late in the summer, Powhatan sent a small party to Jamestown with food to trade. It was mainly a spy mission. Powhatan wanted to know how many whites there were and whether they would trade their muskets and cannons for corn. Their answer was no, and Powhatan didn’t like it. For a few months, a tense, uneasy truce hovered over coastal Virginia. By autumn, the settlers, who did not know how to hunt or plant in this climate, were beginning to starve.

In December, a red-bearded English adventurer named John Smith took a party of nine other settlers to explore what they called the James River. They were after food and gold, and they sought a path to the Pacific Ocean, which they believed was nearby. A large hunting party of Pamunkey Indians surprised the British and captured Smith. They marched him from village to village, where local chiefs questioned him. How many British were there? What were they doing? How long would they stay?

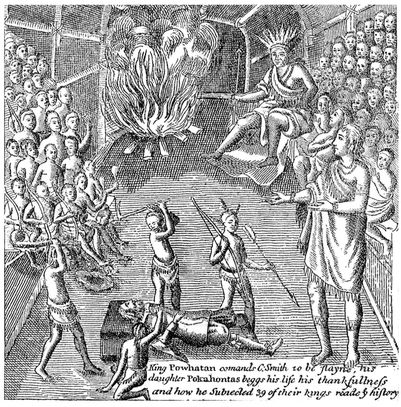

Smith gave little information away. Finally he was taken to Werowocomoco to appear before Powhatan in his great longhouse of arched saplings. After several hours of interrogation, Powhatan abruptly ordered his chiefs to kill Smith. His warriors seized Smith, shoved him forward, and forced his head down upon two large stones. Braves lifted their stone clubs above their heads and prepared to smash them down onto Smith’s skull. Then, according to Smith, a girl rushed forward, placed her own head on top of Smith’s, and begged Powhatan to spare Smith’s life. Powhatan hesitated, then stopped the execution. Two days later, Powhatan adopted the astonished Smith into the tribe as his own son—and as a chief himself. “You may call me Father,” he told Smith. Pocahontas, he said, referring to the girl who had saved Smith, was to be his guardian and sister.

A BRAIN-SAVING GESTURE

“Princess Pocahontas hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine. Not only that, but she so prevailed with her father that I was safely conducted to Jamestown.”

—John Smith

In this drawing from John Smith’s General Historie of Virginia, Pocahontas begs for Smith’s life, as Powhatan’s braves prepare to end it.

Red-haired, short, and feisty, John Smith was a lifelong adventurer. As a boy, he sold his schoolbooks to run away to sea.

Historians still debate what really happened that day. Smith’s description leaves little doubt that Pocahontas really put her head on his. But why? Love? Compassion? One theory is that the whole episode was scripted by Powhatan. If Smith was adopted as a chief, he would have to offer gifts, as other chiefs did. Powhatan wanted those cannons. And if he made Pocahontas Smith’s sister, she would have a reason to spend time in Jamestown, where she could spy for Powhatan. Another theory is that Pocahontas was genuine peacemaker who recognized Smith’s leadership and respected him too much to let him die without trying to save him. Pocahontas shuttled back and forth between Werowocomoco and Jamestown in the winter and spring of 1608. She played with the English boys, challenging them to races, seeing who could jump the highest. They taught her how to do cartwheels, which she learned quickly. Smith wrote that she got so good that she would cartwheel through the dusty clearing at Jamestown, laughing the whole time. She and Smith taught each other words from their languages. A deep friendship grew between them.

Still, the tension deepened between the two sides as the British refused to part with their firearms. One day, when a group of Indians seemed to be surrounding Smith in a cornfield, he whipped out his pistol and took seven of them captive. Pocahontas, acting as her tribe’s official ambassador to the British, appeared before the Jamestown ruling council and coolly demanded their release. The settlers let them go.

Late in 1608, yet another shipload of British settlers arrived. More guns, more round-eyes hungry for corn, not one of them respecting Powhatan as king. Powhatan told his people not to trade with the British anymore, and he ordered Pocahontas to stay away from Jamestown. This was a deep blow to Pocahontas, for now she was truly living in two worlds. It meant not seeing her “brother,” a man who was opening her eyes to a wider world and a new language. And yet she was loyal to her people. Later, when she heard her father and several of his braves plotting to trap and kill Smith, she had to choose. With no time to lose, she slipped away and raced through the woods to warn him, then quickly returned home.

In the fall Smith abruptly left Virginia for England without saying good-bye to Pocahontas. She assumed he was dead, for she could not believe he would simply abandon her. With Smith gone, the Indians surrounded the fort at Jamestown and kept the settlers from getting food. The British later called it the “starving time.” Powhatan moved his inner family farther away from Jamestown and kept Pocahontas away from the British for three years.

During that time Pocahontas married a brave named Kocoum. Little is known of him, but the couple was no longer together in 1613 when the British next came upon her. At that time she was living apart from her father in a village near the river, not far from where a British ship was anchored. With the aid of friendly Indians, the British lured her aboard, taking her hostage. They believed Powhatan would do nearly anything, maybe even surrender, to get her back. Day after day Pocahontas expected her father to come to her rescue, but Powhatan never appeared. As the months dragged by, she began to adopt white ways. She traded her soft deerskin garments for stiff, scratchy petticoats and began to walk with small steps instead of long strides. She perfected her English. She attended Bible classes and, as always, learned quickly. She was baptized as a Christian and given the name Rebecca.

When she was eighteen, Pocahontas married John Rolfe, a twenty-eight-year-old English tobacco planter whose first wife had died on the voyage from London to Virginia. It was the first official interracial marriage in America. Rolfe gained permission from British authorities by convincing them that Pocahontas offered valuable, living proof that the Indians of Virginia could be civilized.

A portrait of Pocahontas, painted in England when she was about twenty and the talk of London society

In 1616, Pocahontas and Rolfe sailed for London to show off their new baby, Thomas, and to raise money for the Jamestown settlement. Sponsors of the Jamestown Colony were eager to show Rolfe’s Indian bride to Londoners. They hoped that the elegant, English-speaking princess would prove to potential investors that Virginia was indeed a safe place for British money.

When Pocahontas first caught sight of the hundreds of tall ships in Plymouth Harbor and saw London’s bustling streets and impressive buildings, perhaps she finally understood the power of the round-eyes and the hopelessness of her tribe’s situation in Virginia.

In the next weeks, Pocahontas was presented to London society at a series of balls and dinners. Dressed in gowns and petticoats, she became a sensation, a celebrity. At one such reception, the great English playwright Ben Jonson is said to have simply stared at her, unable to speak for forty-five minutes. John Smith was also in London, but he didn’t contact Pocahontas until he learned that she had become gravely ill. The two had a painful reunion of several hours. Unable to forgive him, she turned her back to him and addressed him impersonally as “Father.” The visit seemed to sadden her deeply.

While Pocahontas was in London, a British artist was hired to paint her portrait. The finished canvas shows a poised young woman in a feathered top hat and lace collar, looking straight back at the painter with large, clear eyes that reveal little of her feelings. Ever since Columbus, boys and girls of Europe had heard stories of the naked, bloodthirsty savages who waited across the ocean to fill Europeans’ bodies with arrows. But here was a princess, a young mother who dressed elegantly and spoke perfect English. Pocahontas gave Europeans an Indian with a human face, a soul, and a conscience.

She died in 1617 at the age of twenty-two while preparing to sail back to Virginia. When Powhatan learned that Pocahontas was dead, he gave up his throne and went to live among the neighboring Patomics. He died a year later. Pocahontas’s son, Thomas, went to Virginia in 1635 and became a successful planter.