“Wee marched to the King [Powhatan], who, after his old manner kindly received him, especially a boy of thirteen years old called Thomas Savage.”

—John Smith, A True Relation of Virginia Since the First Planting of That Colony

Jamestown, Virginia, 1608

Early in 1608, a second group of English settlers arrived in Jamestown to reinforce the first group, who were starving and under attack from Powhatans, part of the Algonquian nation. Only one boy came with the second group. He was thirteen-year-old Thomas Savage, who left England looking for adventure. He became the first British spy in the New World, and he got all the adventure he could handle.

Unlike most of the first English children in America, Tom Savage was probably not an orphan. More likely he was the son of people who owned land in the city of Chester, near Liverpool. Though he didn’t write about his early life, historians think Tom ran away to London because he was determined to see Virginia.

Many Britishers were thinking about Virginia in 1608. The Virginia Company, sponsor of the colony at Jamestown, tried to attract investors and settlers to the colony by describing Virginia as a paradise. It was advertised as a land of “fair meadowes and goodly tall trees” where colonists snacked on strawberries big enough to choke them, hunted raccoons the size of foxes, and plucked grapes from vines as big around as a man’s thigh. Supposedly, it was almost impossible not to find gold.

Once he got to London, Tom made his way to the docks and introduced himself to a one-armed ship captain named Christopher Newport, the very man who had taken the first group of colonists to Virginia. Now he was back for more colonists and fresh supplies. Captain Newport must have liked what he saw of this eager boy. He offered Tom a free trip to Virginia if Tom would agree to become Newport’s personal indentured servant. At sea, Tom would cook, rig sails, and scrub decks. Once they got to Virginia, he would become a field hand or Newport’s household servant. After seven years, the contract would run out and Tom would be free to seek his fortune.

Advertisements promising the riches of the New World encouraged many English to emigrate.

YOUNKERS

Four English boys were among the first settlers at Jamestown. All were orphans from London. Their names were Samuel Collier, Nathaniel Peacock, James Brumfield, and Richard Mutton. The men called them younkers, meaning “youngsters”—from the Dutch word jonker, “young nobleman.”

Had Tom known what Virginia was really like, he might not have been so eager. Jamestown was hardly a paradise. Settlers had to work hard to find food and clear the wilderness, and the Indians were unfriendly and aggressive. Most of the settlers in Jamestown were lazy investors from London who were out to find gold quickly and then sail back home to spend it. These city men who had never hunted or farmed spent their afternoons stumbling along riverbanks, panning for gold in their silk breeches.

By the time Tom arrived at Jamestown with the second group of settlers, in January of 1608, about two-thirds of the Englishmen were dying from starvation, malaria, and pneumonia. Others had been killed by Powhatan’s warriors. One of the four original younkers (see sidebar) had already taken an arrow in the heart.

John Smith, the leader of the Jamestown Colony, desperately wanted to know more about the Indians he faced. How many were there? Where were their villages? Which tribes, if any, would trade corn for beads—not guns—and teach the English settlers to plant it? He needed a spy.

Smith learned that tribes sometimes traded children so that the entire Powhatan confederacy could learn from the exchanges. He came up with an idea: Why not offer Powhatan a British boy in exchange for an Indian boy who could be given a chance to sail to England? Powhatan surely had the same questions about the British that Smith did about Powhatan’s tribes. And once the Indian boy saw London, he would surely report back that the Indians had no chance to succeed against the powerful British.

Smith convinced Captain Newport to give up his servant for the good of the colony. He offered the boy a deal: If Tom would go live among the Indians for a time and report back with information when he could, he would be granted freedom from his indenture early. Tom agreed. In proposing the exchange, the British told Indian messengers that

Captain Newport was the colony’s ruler and that they were offering Powhatan Newport’s only son. Powhatan sent a return message saying he wanted to see the boy first.

A few days later Tom, dressed as a gentleman, hiked off with a party of British settlers through the forest to Powhatan’s village of Werowocomoco. The group was led by a trumpeter who played flourishes as if he were announcing a king. After formal greetings, Newport presented his “son,” Thomas. The great chief inspected Tom carefully, then accepted him and gave the British a young brave named Namontack. Of course, Namontack was a spy, too, with orders to go to England and report back with information on the round-eyes’ strength.

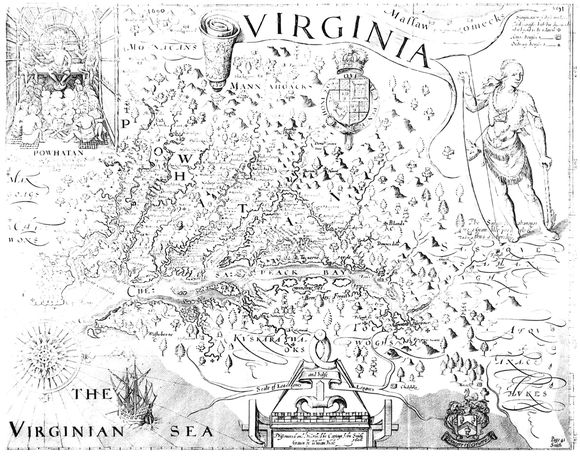

John Smith’s map of Virginia, drawn in 1612. He hoped and believed that the Pacific Ocean was just to the west.

PARADISE

“We have discovered the goodliest soil under the cope of heaven, so abounding with sweet trees, that bring such sundry rich and pleasant gums, grapes of such greatness, as France, Spain, nor Italy have no greater.”

—A widely read description of Virginia written by British explorer Ralph Lane in 1585

TUFFTAFFETY MEN

John Smith looked down on the lazy gentlemen settlers. He thought they looked ridiculous in their breeches and blouses made of a silken fabric called taffeta. He scornfully called them “tufftaffety men.”

After the colonists left, Tom dropped his London clothes and tied a fringed deerskin cloth around his waist. Algonquian boys painted his chest and back with the juice of the pocan plant to protect him from spirits of the forest. They taught him to stalk deer on all fours with a bow slung over his shoulders. Just a year before, Tom had lived in crowded England. Now he was living in a village of huts held together by woven fibers and sleeping in Chief Powhatan’s longhouse, surrounded by warriors.

Tom lived the razor-edged life of an undercover agent. He was forbidden from going to Jamestown by himself, though at least once he was able to warn the colonists of an attack. When British colonists learned that the Indian boy, Namontack, had been killed in a quarrel at sea, Tom’s situation became even more dangerous. If Powhatan found out, he might take revenge by killing Tom. As months and then years went by with no word from Namontack, the secret got harder and harder for the British to keep.

After three years, Powhatan finally let Tom visit Jamestown on his own. This time the British decided he would not return, even if Powhatan’s warriors came after him. With John Smith back in England, Tom was now the colonist who knew Algonquian words, customs, and leaders the best. At sixteen, he had become one of the most important figures in the Jamestown Colony and was given his freedom from indenture. To reward his courage, the British granted the teenager the military rank of ensign and declared him Interpreter for the Colonies.

In 1619, after Powhatan died, a new chief named Debeavon gave Tom nine thousand acres on a peninsula on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Tom became the first white settler in that area, which today is known as Savage Neck. He married a British settler named Anna Tying in 1624. They had one child, a son. Tom Savage died in 1627.