“[Boys and girls of] twelve or fourteen yeers of age, or under may bee kept from idlenesse, in making of a thousand kindes of trifling things, which wil be good merchandize for that country.”—Richard Hakluyt of London, explaining why he favored sending children to the New World

London and Virginia, 1619

Though Britain’s King James declared smoking ugly to look at, nasty to smell, bad for the brain, and awful for the lungs, the British loved to smoke, and they adored John Rolfe’s new Virginia blend. The Jamestown Colony suddenly needed more land to grow it on and workers to plant and harvest the crop. To satisfy the smokers of London and bankroll the colony, Virginians turned to a great, cheap labor supply: English children.

The seventeenth century was an unsettling time for the youth of England. In the countryside, peasant farmers were driven off their land by landlords who wanted it for raising sheep. Many large families were broken apart, and thousands of children ran away to live in the streets of England’s rapidly growing cities.

City officials had responsibility under England’s Poor Law to take care of orphans and abandoned children. The usual practice was to “bind them out” to families who would take in more children. But suddenly there were way too many children. When John Rolfe’s Virginia blend of tobacco began to take off in London, a logical solution arose: Why not ship England’s orphans to Jamestown’s tobacco fields?

In 1619, the Virginia Company wrote to the London Privy Council:

“We pray your Lordship to furnish us with one hundred [children] for next spring. Our desire is that we may have them of twelve years old and upward with allowance of three pounds apiece for their transportation and forty shillings apiece for their apparel … They shall be apprentices the boys till they come to twenty-one years of age the girls till like age or till they be married.”

The request was granted and one hundred children sailed to Virginia. The next year the company went even further. They asked London’s leaders for permission to make children go to Virginia, and, once they were there, for permission to “imprison, punish or dispose” of children who didn’t follow their orders. In making this request, they described Virginia’s tobacco fields as an ideal reform school and asked the city for one hundred children “of whome the City is especially desireous to be disburdened, and in Virginia under severe masters they may be brought to goodness.” Again, permission was granted.

A COLONY FOR SMOKERS

Though the king railed against “the black stinking fumes,” London coffee shops grew ever smokier with Virginia tobacco. About twenty-five hundred pounds were exported to England in 1616. Two years later, the figure was fifty thousand pounds, and by the Revolutionary War it was one million pounds—and tobacco ruled Virginia.

NEW HELP

In 1619, the Virginia Company offered two other new sources of help to Jamestown besides boys. It sent a shipload of “young, handsome and honestly educated maids” from England to be wives to the male settlers. These were poor women and teenage girls who wanted something better than homelessness in London but had no money to pay their fare. When the boat arrived in Jamestown, men clustered eagerly at the dock to see the women. The price of a wife was 120 pounds of tobacco to the company. The women were called “tobacco brides.”

And in late summer, there was a second new source of labor. John Rolfe wrote in his journal: “About the last of August came in a Dutch man of warre that sold us twenty negars.” These twenty Africans were the first of a great wave of men, women, and children from Africa who came to America’s shores in chains. One was a baby named William, the first black child born in Colonial America.

They worked in the tobacco fields with white indentured servants. At first, the British gave the African servants freedom after several years of work. But in 1662, a law was passed in the Virginia colony that said children were slaves if their mother was a slave, and free if she was not. By then, almost all African-American adult women were slaves, so of course nearly all black children became part of their white master’s property, just like his furniture and livestock and tobacco and land.

Soon there was a thriving market for children. Investors in the Virginia colony hired people to lure children aboard ships with scraps of food and tales of adventure. Some children were offered indentures, contracts that provided a free trip to Virginia in exchange for years of labor. Others were simply kidnapped or “spirited” away. One boy, rescued from a ship about to sail for Virginia, testified in court that he had been snatched from his parents and forced onto a ship full of crying children on the river Thames. He said he could see his parents from the ship but they didn’t have enough money to buy him back from his captors. A London girl testified that a “spirit” named Sarah Sharpe was guilty of “violently assaulting her, tearing her by the hair of the head, and biting of the arm” and for being “a common taker up of children into ships.”

Laws were passed to protect children against spirits, but they stayed in business until large numbers of families immigrated to the New World, bringing their own children with them.

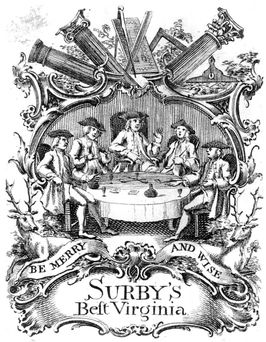

This trading card from 1750 advertised a brand of Virginia tobacco to English smokers. Tobacco from the New World turned out to be far more valuable than gold.