“Jaghte oghte.” (Maybe not.)

Deerfield, Massachusetts, 1704

Many white children grew up among Indians in the Colonial years. Most were trapped in a bitter struggle between Britain and France for the control of North America, in which Indian tribes took sides. Canada was then called New France, and the northern part of the British colonies was known as New England. Both nations claimed the same territory, both built forts, and both tried to recruit Indian allies. British colonists were predominantly Protestants, while the French insisted that all inhabitants of New France, including Indians, be Catholic. Those who lived in settlements near the border were in mortal danger. One of the most dangerous places to live in those days was the remote British outpost at Deerfield, Massachusetts. Deerfield was raided and burned six times in the 1690s alone. An especially brutal attack took place on the morning of February 29, 1704. Striking at dawn, Abenaki and Mohawk warriors and their French allies swept down upon the town, massacring families in their sleep. They captured more than one hundred prisoners and marched them through the snow all the way to Canada. The hostages included a well-known Puritan minister named John Williams, his wife, and five of their children. Reverend Williams’s youngest daughter, Eunice, was seven years old on the night the raiders came.

Eunice Williams was born into a family of famous Puritan church leaders. Her uncle and cousin were the great Boston ministers Increase and Cotton Mather. Her father, the Reverend John Williams, was the most respected man in Deerfield. By the time the raiders stormed over the Deerfield fence, Eunice had already made great progress in reading her Bible, and she knew her catechism by heart.

But on that horrible day, her life changed by the hour. By noontime, when Eunice and the other shivering captives turned back to look at Deerfield from a high hill, they saw that their town had been destroyed. Her two younger brothers were dead. And now she and her family were prisoners.

In this woodcut from The Deerfield Captive, published in 1832, the Reverend John Williams rises to defend his family from attack.

PELT WARS

Part of the fight between the French and British was for control of beaver skins, called pelts. The fur was extremely valuable, especially after Britain’s King Charles I decreed in 1638 that all hats made in the colonies had to contain beaver fur. But French trappers had been in beaver country before the British, and, of course, Native Americans before that. Many battles were fought for control of the valuable pelts, with the big losers being the beavers themselves. The Hudson’s Bay Company sold 26,750 beaver pelts in one day in 1743. It took only a few decades to push beavers to the brink of extinction (from which they have since recovered).

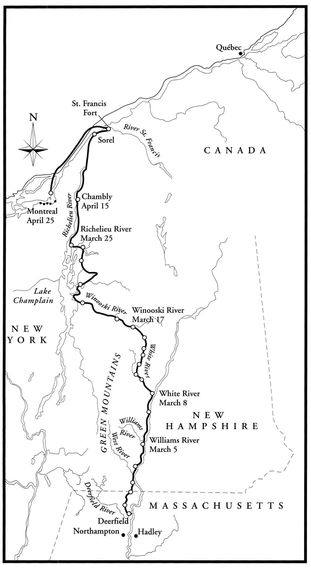

The route of Eunice Williams’s two-month-long journey—most of it taken on the back of a Mohawk warrior—from Deerfield to Montreal

The next morning they began to trek single file through the snow toward Canada. Anyone who couldn’t keep up was killed to save time and energy. Early in the journey Eunice’s mother, still weak from having just given birth, broke through the ice and soon could barely move her frozen feet. She was quickly murdered. Partway through the journey, the French and Indian captors separated Eunice from her father, sister, and three brothers. Bundled in a blanket, Eunice was hoisted up onto the back of a brave who carried her hundreds of miles to Kahnawake, a Mohawk settlement near Montreal.

Eunice didn’t see her father again until the following spring, when French Jesuit priests and Mohawk leaders gave them two brief chances to talk. She was healthy, she told him, but scared. She reported that her captors mocked her religion and forced her to say prayers in Latin—the language of the Roman Catholic Church. John Williams, furious, told her to cling to her catechism and the prayers she had learned, and she would be all right. And then he was led away.

Reverend Williams did everything he could to reunite what was left of his family. Within two years he was able to enlist British diplomats to secure his own release and to win the freedom of all his children except Eunice. For some maddening, mysterious reason, the Mohawks refused all proposals to trade hostages for her. They wouldn’t even let anyone see her. Year by year, John Williams became more desperate, and the strange story of Eunice Williams spread throughout the land. Each Sunday, in meetinghouses all over New England and New York, worshipers prayed that God would enter the hearts of the “savages” who held Reverend Williams’s daughter.

No Englishman saw Eunice again until 1713, the year she turned sixteen. That May, an English diplomat named John Schuyler was allowed to visit her at the home of a priest in

Montreal. Eunice sat down on the dirt floor in the center of the room and gazed directly at Schuyler. He was amazed by her appearance: Eunice’s leggings were fringed with moose hair and bound together with porcupine quills. Her hair was heavily greased and pulled back with a ribbon of eelskin. There were spots of red paint on her cheeks and forehead. A man sat silently behind her. The priest introduced the man as Eunice’s husband, Arosen, or “squirrel” in Mohawk. And Eunice, who could no longer speak English, wasn’t even Eunice anymore. Now she had a Catholic name, Marguerite. She seemed happy and settled. She didn’t want to leave.

She remained silent for two hours as the Englishman begged her to return home. Finally, through a translator, she said her only words of the visit: “Maybe not.” Schuyler described her on that day as “bashful in the face, but … harder than Steel in her breast.”

Word of the encounter raced through New England meetinghouses. It didn’t make sense: How could Eunice Williams willingly turn her back on her great family to live with savages? They must have taken over her mind. No one could accept that she could have chosen to live among the Indians.

In 1740, when she was forty-three, Eunice finally returned to Massachusetts as a visitor. Her father was dead, but her brothers Stephen and Eleazer were still alive. Rather than staying with her original family, she camped out with Arosen in an orchard. Wrapped in blankets, she attended a church service, during which worshipers offered impassioned prayers for her soul. Those who had known her as Eunice Williams prayed that God would help her come to her senses and remain among them. She listened respectfully, and greeted those who approached her with courtesy. And then, when she felt it was time, she went home.

Eunice made several more visits and formed a warm relationship with her brothers—who never gave up hope—but she always returned to her home in New France. She and Arosen had two daughters and a son. She died peacefully in her village of Kahnawake at the age of eighty-nine.

British authorities didn’t take kindly to Native Americans who sided with the French against the British in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This proclamation offers a reward to anyone who kills a Penobscot Indian. A dead male twelve years or older brought fifty pounds, while his scalp alone brought forty pounds. Adult females and boys under twelve were worth twenty-five pounds, and girls under twelve, twenty pounds.