YOUNG SLAVEOWNERS

Eliza Lucas was one of many young people growing up on plantations who inherited slaves or became responsible for directing their work. George Washington inherited his first slaves at eleven, Thomas Jefferson at fourteen. Eliza Lucas accepted slavery and treated her slaves as well as her time and place allowed. She taught two slave girls to read, and then assigned them to teach the others in a school she started for slaves in her area. In 1745, she wrote this vow to herself:

“I am resolved to make a good Mistress to my servants, to treat them with humanity and good nature; to give them sufficient and comfortable clothing and provisions, and all things necessary for them. To be careful and tender of them in their sickness, to reprove them for their faults, to encourage them when they do well, and pass over small faults; not to be tyrannical, peavish or impatient towards them, but to make their lives as comfortable as I can.”

“The longer time we are awake the longer we live … Thus I have the advantage over the sleepers in point of long life.”

Wappo Plantation, South Carolina, 1740

As the British fought France for control of New England, they were also battling Spain for the West Indies and the southern part of North America. Spain controlled Florida, while Britain maintained a very shaky upper hand in Georgia and the Carolinas. Colonel George Lucas commanded British naval forces at the Caribbean island of Antigua. Like many officers, Colonel Lucas was also a wealthy planter. When his wife fell ill during a break in the fighting, he moved his family to the British colony of South Carolina, which had a milder climate. He bought a house in Charleston, three rice plantations, slaves, horses, seed, and farm equipment and set about life as a rice planter. But then fighting resumed in the Caribbean, and Lucas was quickly summoned back to Antigua. His wife was too ill to accompany him, so he left everything—the plantations, the house, twenty slaves, and the care of his wife and younger daughter—to his sixteen-year-old daughter. Colonel Lucas had only one comforting thought: If any girl on earth could handle such responsibility, it was Eliza Lucas.

Shortly after her father sailed away, Eliza Lucas wrote in her journal that she “could have been moped,” but she wasn’t the moping kind. She was a doer. First she moved her mother and sister, Polly, out of Charleston and into a house in the country, where she could be close to the fields and away from gossipy society. Then she began to learn the life of a planter. Within a matter of weeks she wrote to her ex-teacher in London:

“I have the business of three plantations to transact, which requires much writing and more business and fatigue of other sorts than you can imagine. But lest you should imagine it too burdensome to a girl at my early time of life, I think myself happy that I can be useful to so good a father, and by rising very early I find that I can go through much business.”

Ignoring the elegant plantation balls and porch parties of the Carolina rice country, Eliza filled her journal with daily tributes to oak trees, flowers, and mockingbirds. She

planted orchards and flowers and fig groves. Soon her neighbors were full of curious gossip about the pretty, highly eligible young girl who dared to live out in the country with no man to protect her from Spanish soldiers or rebellious slaves. Eliza offered this description of her life in a letter to an inquisitive neighbor lady:

“In general I rise at five o’clock in the morning, read till seven—then take a walk in the garden or fields, see that the Servants are at their respective business, then to breakfast. The first hour after breakfast is spent in music, then … [learning] French or shorthand. After that, I devote the rest of the time until I dress for dinner to our little Polly and two black girls who I teach to read … The first hour after dinner is at music, then in needlework till candle light, and from that time to bed time I read or write. Thursdays the whole day is spent in writing, either on the business of the plantations or on letters to my friends. [Also] I have planted a large fig orchard, with design to dry them and export them.”

Word traveled fast. Another neighbor warned Eliza that she could spoil her good looks by getting up so early. Her reply came quickly:

“Whatever contributes to the health and pleasure of mind must also contribute to good looks … and if I should look older by [rising early], I really am so; for the longer time we are awake the longer we live … Thus I have the advantage over the sleepers in point of long life.”

The prolonged conflict between Britain and Spain crippled South Carolina’s economy. When a Spanish naval blockade prevented South Carolina rice from reaching the West Indies, Carolina families began to suffer. The colony depended too much on rice and desperately needed new crops to sell. Here was just the kind of challenge that triggered Eliza’s passion for experimentation. Using seeds her father sent her, Eliza had her slaves plant indigo, ginger, cotton, lucerne, and cassava. Soon she focused her attention on indigo, a bushy plant that produces a dark blue dye. British families used the dye to brighten wool and cotton. With no other supplier, Britain was forced to buy all its indigo from rival France. Eliza set out to make South Carolina Britain’s main supplier instead.

An indigo plant

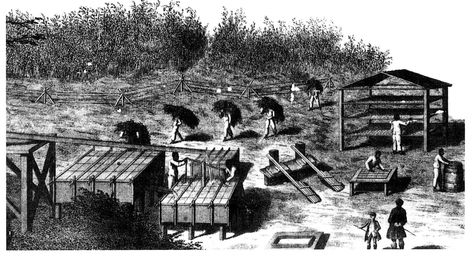

Slaves haul freshly cut indigo plants to be processed into dye on a South Carolina indigo plantation. The leaves were soaked in vats until they released their dark blue dye, which hardened and was sold in the form of dry cakes.

It wasn’t easy. Her first crop froze. Worms ruined the second crop, and the third season produced only a hundred plants. Colonel Lucas tried to help, sending his daughter more slaves and an overseer to manage them. Then he sent a dye maker, a sour man who deliberately ruined a whole year’s crop.

Colonel Lucas tried to send Eliza a husband, too. In 1740, he volunteered to match her with an elderly man who, he said, would be perfect for her. He could come as soon as she gave the word. Eliza replied respectfully:

“A single life is my only Choice and if it were not that I am yet but Eighteen, I hope you will put aside the thoughts for my marrying two or three years at least.”

Colonel Lucas wrote back with a second candidate. Now Eliza was firmer:

“[I] beg leave to say to you that the riches of Peru and Chile if he could put them together could not purchase sufficient esteem for him to make him my husband.”

When Eliza finally produced a successful indigo crop in 1744, she offered free seeds to all neighbors who would agree to plant indigo the following year. Most accepted. Within a few years, South Carolina’s planters were raising so much indigo that Britain no longer needed French supplies. With the crop in good shape, Eliza turned her attention elsewhere. She married a man of her own choosing, a neighboring planter about twice her age named Charles Pinckney who had helped her develop the indigo crop.

She became the mother of three children and later became a well-known patriot when the colonies fought for their independence from Britain. Two of her sons were Revolutionary War heroes. When Eliza Lucas Pinckney died in 1793, George Washington helped to carry her coffin.