LIFE OF A LOBSTERBACK

The life of a British soldier in the colonies was no picnic. Most didn’t want to be there. Some were criminals who chose being a soldier in Boston over a jail in London. They were supposed to look like models of authority. It took them hours to get into and out of their tight, scratchy clothes. They were paid only two cents a day, which meant if they had families they almost had to take a second job. But that meant taking a job away from a colonist. No wonder they felt hated.

FORTY SHILLINGS REWARD

“Ran away this morning from the subscriber, an Apprentice BOY named James Hoy, near 18 years old, about 5 feet 8 inches high, fair complexion, and hair tied behind. He took with him a brown jean coat, grey surtout, new shoes, round felt hat, and many other articles of cloathing. Whoever brings him back or confines him in gaol, so that he can be had again, shall receive the above reward.”

—An advertisement placed by John Farran, Philadelphia, June 26, 1770

“We have been told that our Struggle has loosened the bands of Government every where. That Children and Apprentices were disobedient—that schools and Colledges were grown turbulent—that Indians slighted their guardians and Negroes grew insolent to their Masters.”—John Adams, reporting what he had heard about Boston while he was away in Philadelphia

Boston, Massachusetts, 1770

Boston was a red-hot volcano in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, and young people were at the molten core. Whig children (loyal to the colonies) and Tory children (loyal to Britain) confronted one another throughout the city. In a Dorchester church “the boys were so turbulent, the spirit of independence so riotous, that six men had to be appointed to keep order.” A fight even broke out in the Harvard College dining hall when Tory students began to noisily slurp English tea. Angry young patriots smashed their teacups against the wall. The patriot boys had to pay for the damages, but no one could bring tea into the dining room anymore. In 1768, Britain sent soldiers to Boston “to keep order.” When Americans refused to pay for their food and lodging, the soldiers pitched tents in the middle of town and stayed up nearly all night playing their drums and bugles as loudly as they could. Angry crowds, including many teenage boys, formed near the British army posts and outside customs buildings where British tax collectors worked. It was clear that before long something would erupt.

On a winter morning in 1770, about 150 Boston schoolchildren gathered outside the shop of Theophilus Lillie, a merchant who had chosen not to boycott British goods. The children were there to make him pay for it. One boy carried a hand-shaped sign with a pointed finger and the word IMPORTER painted on it. Taking a boost from a couple of friends, he shinnied up a signpost and nailed it to the top, aiming the finger at Lillie’s door.

A few minutes later Ebenezer Richardson, a British customs inspector who lived in the neighborhood, came around the corner and saw the sign. He rushed toward it and tried to tear it down. Students showered him with stones, opening a gash in his head. Covering his bleeding scalp, Richardson staggered home and grabbed his musket from the wall. He

stormed up to the second floor, flung open a window, took aim, and blasted a ball of lead into the crowd. Eleven-year-old Christopher Seider was stooping down to pick up a rock when the shot struck him in the head. He died later the same day.

That shot seemed to unite the whole town against the British. Four days later, six young boys carried Christopher’s coffin through downtown Boston to the burial ground. The parade that followed—led by five hundred children—was nearly a mile long.

Two weeks later, on the frosty evening of March 5, 1770, a young barber’s apprentice, Edward Garrick, walked past Hugh White, a British soldier standing guard outside the British customhouse, where taxes were paid. The sight of White’s red coat brought back the memory of Christopher Seider and reminded Edward that he also had a personal problem with British soldiers: He thought White’s captain owed his master money for a haircut.

Edward walked back to White, stood before him, and called White’s captain mean, which meant “cheap.” A few words later, the two went for each other. White swung his rifle butt at Edward’s ear, sending him sprawling to the ground. Edward howled for help and a crowd quickly gathered. Someone sprinted inside and rang the fire bell, and dozens more poured from houses and shops out onto King Street. Soon White stood alone against hundreds ready for his blood. He yelled for reinforcements, and eight armed British soldiers appeared.

APPRENTICES

Apprentices were in the thick of the fight for independence—from Britain and from their masters. They were boys who signed a contract with a craftsman to learn a trade. The master was supposed to provide food and a decent place to live, and to teach the trade while the apprentice worked for free for up to seven years. Most apprentices hated the arrangement. Besides getting no pay, they were often fed badly and kept apart from the master’s family. Frequently the master waited until the very end of the contract to teach the trade, so the apprentice would not run away early.

Apprentices looked up to Revolutionary leaders who had once been apprentices themselves. They all knew that Tom Paine and Ben Franklin had run away from their masters—Franklin’s autobiography was a favorite book. Ebenezer Fox, a fifteen-year-old apprentice to a Boston wigmaker, expected a better deal for apprentices after the war. In 1779, he wrote: “I and other boys situated similarly to myself, thought we had wrongs to be redressed; rights to be maintained … We made a direct application of the doctrines we daily heard, in relation to the oppression of our mother country, to our own circumstances … I was doing myself a great injustice by remaining in bondage, when I ought to go free; and that the time was come when I should liberate myself.”

But the better deal didn’t come. After the war, new laws were passed that gave apprentices even less freedom. In New York, apprentices caught running away from their masters had to serve double time. Some apprentices organized and walked out of their shops, but things didn’t really change until years later when factories replaced shops.

Seventeen-year-old Samuel Maverick, an apprentice just home from work, was eating supper when he heard the fire bell. He stuffed down a final mouthful and plunged outside into the angry mob. Working his way to the front, he found himself pressed against British muskets. The soldiers were nervously dodging heavy chunks of ice thrown at them from the back of the crowd. People were calling them lobsterbacks and redcoats. A few were daring them to shoot.

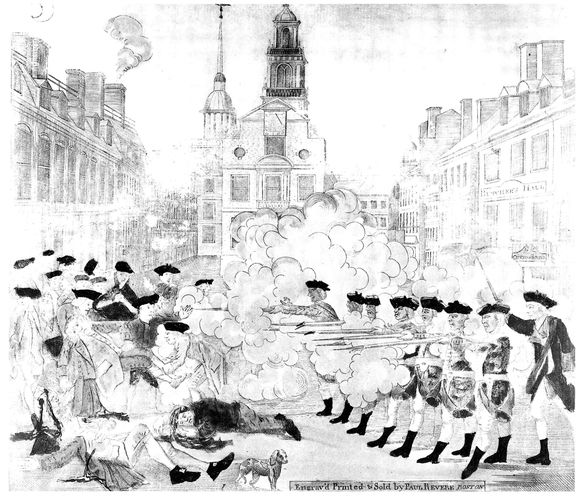

This famous engraving by Paul Revere, depicting well-disciplined British troops calmly firing into a peaceful gathering of Boston citizens, heated anti-British passions to a boil. It hardly mattered that the scene was inaccurate.

Then someone threw a club and struck a British soldier in the head. The soldier fell, then scrambled to his feet and fired into the crowd. Samuel Maverick turned and tried to push back through the wall of people. There was another shot, and another. Samuel was covered with blood. He crawled home and died in his mother’s arms.

The British kept firing. When it was over, five Bostonians were dead and six more wounded. Two of the wounded were seventeen-year-old apprentices, like Samuel Maverick. The British soldiers were arrested and tried for murder. Paul Revere, an engraver and silversmith (who later became famous for his midnight ride), drew a picture of the shootings and etched it into a piece of copper so that it could be reproduced again and again. It showed—inaccurately—an even row of British soldiers calmly shooting at unarmed and peaceful citizens. Revere’s patriot friend Sam Adams dubbed the event the “Boston Massacre.” The picture and the story spread like fire throughout the colonies. And helped ignite a war.