MILITIAMEN

Militiamen were local volunteer soldiers organized within each colony. Militiamen met on training days called by their captain to practice fighting moves and shooting. All healthy men between sixteen and sixty who weren’t in the paid, regular army were supposed to volunteer. They had to bring their own gun, bullets, and powder to training, and they were supposed to fight when their commander called them. Each colony gathered ammunition and stored it in a central place for a major emergency. The arsenal at Danbury was one of those places, and the British raid was a major crisis.

“The British are burning Danbury! Muster at Ludington’s!”

Fredericksburg, New York, April 26, 1777

Nearly everyone has heard of the midnight ride of Paul Revere. That’s mainly because Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a poem about it soon after it happened. But far fewer people know that two years later a sixteen-year-old girl rode much farther over rougher roads. Alone and unarmed, Sybil Ludington raced through the night for freedom.

Just after dark on the rainy evening of April 26, 1777, Colonel Henry Ludington, commander of a regiment of militiamen near the New York—Connecticut border, heard a rap at his door. Outside stood a saluting messenger, rain streaming from his cape. His words came fast. British soldiers had just torched the warehouse in Danbury, Connecticut. Food, guns, and liquor belonging to the Continental army were being destroyed. Drunken soldiers were burning homes, too. Could Colonel Ludington round up his men right away? It was easier said than done. Colonel Ludington’s militiamen were farmers and woodsmen whose homes were scattered throughout the countryside. Someone would have to go get them while the colonel stayed behind to organize them once they arrived. But who? Who besides he himself knew where they all lived and could cover so many miles on horseback in the dead of night? Deep in thought, he heard his daughter Sybil’s voice. She was saying that she wanted to go.

For Sybil Ludington it was an unexpected chance to help the war effort. As the oldest of eight children, her days were filled with chores and responsibilities. Still, each week when her father’s men drilled in their pasture, she paused from her work to watch them. She wished she could fight. People kept saying she was doing her part for liberty at home, but she wanted to do more. Suddenly, with this emergency on a rainy night, she had a chance.

In 1975, the U.S. Postal Service issued a Sybil Ludington stamp to mark the American Bicentennial.

Her father looked at her. How could he let her take such a risk? The whole countryside was full of armed men. There were skinners and cowboys who stole cattle for the British, soldiers from both sides, and deserters trying to get back home under cover of darkness. But Sybil was right: She knew every soldier in her father’s unit and she was a fine rider. Rebecca, her next oldest sister, could mind the children. Most of them were already asleep anyway.

Colonel Ludington walked with Sybil out to the barn and held a lantern while she threw a saddle over her yearling colt, Star. Together father and daughter went over the names of his men and where they lived. Then the colonel watched Sybil disappear into the darkness.

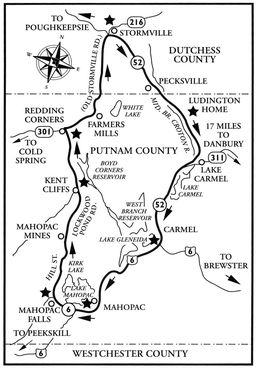

It was raining hard. Sybil put away thoughts of who might appear in the roadway and concentrated on the road map in her head. With no time to lose, she had to reach all the men, taking the most efficient route possible. She picked up a long stick to bang on doors. That way she wouldn’t have to waste time dismounting and getting back on Star. One by one, hearing the rap of the stick, the sleepy farmers cracked their doors open, some poking muskets out into the darkness. Sybil said the same thing to all: “The British are burning Danbury! Muster at Ludington’s!” Once she knew they understood, she galloped off, refusing all offers of rest and refreshment.

It took her till dawn to get back home. She was soaked and sore, but as she rode up to her farm she could hear the sounds of drums and bugles. Many of her father’s men were already there, getting ready to march. Soon her father’s militia set off to join five hundred other Colonial soldiers. They missed the British at Danbury but finally fought and defeated them at Ridgefield, Connecticut, a few weeks later.

Word of Sybil’s night ride got around. George Washington thanked her personally, and Alexander Hamilton wrote her a letter of appreciation. When she was twenty-three, Sybil married her childhood sweetheart, Edmond Ogden, and became the mother of four sons and two daughters. Sybil died in New York at the age of seventy-seven. There is a bronze statue of Sybil Ludington atop Star at Lake Gleneida in Carmel, New York. In 1975, an eight-cent U.S. postage stamp was issued in her honor.

The route of Sybil Ludington’s night ride through the New York countryside

SYBIL RODE FARTHER

On April 18, 1775, Paul Revere raced from Boston to Lexington to warn American rebel leaders, “The British are coming!” He rode fourteen miles on good roads for some two hours, while Sybil Ludington rode all night—nearly forty miles over cart tracks and rutted fields in the blackness of rural farm country.