“I shall never prove a traitor to my country.”

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1780

In 1776, the year the Declaration of Independence was signed, one of every six Americans was of African ancestry. Ninety-nine percent of them were slaves. James Forten was one of about two hundred free blacks living in Philadelphia. He was fourteen years old in 1780.

Whenever an American privateer captured a British ship, practically everyone in Philadelphia lined the docks along the Delaware River to cheer the American sailors as they led the defeated vessel into harbor. Then the crowd surged to the London Coffee House, where the ship’s cargo was auctioned off and the proceeds divided among the American crew. When there was gold aboard, even boys—powder monkeys and cabin boys—soon had pockets sagging with heavy coins. Like many boys in Philadelphia, James Forten wanted to sail aboard a privateer more than anything in the world.

It wasn’t just the money. James wanted to fight for American freedom. He believed the American cause offered a better chance for his people than that of the British, who ran an enormous slave empire in the West Indies. James owed his freedom to his grandfather, an African-born slave who had somehow scraped together enough money to buy freedom for himself and his wife. All their children, including James’s father, had been born free. James had even been lucky enough to go to a school run by a Quaker teacher opposed to slavery. James knew the sweetness of freedom, and he wanted it for everyone.

At first James’s mother was dead set against his going to sea. James’s father had died and James was her only son. She needed him. But he had a powerful argument: The family was living in rags, without even enough money for new shoes. He reminded his mother that a privateer’s wages—four dollars a month—could make ends meet for the family even if there wasn’t any prize money. And if there was, they could breathe much easier. When she nodded her head, James was in heaven.

James Forten, who owed his freedom to his grandfather’s labor, devoted his life to the abolition of slavery and lived to see his sons and grandsons become leaders in the antislavery movement.

SLAVES IN THE REVOLUTION

Slaves fought on both sides of the war between America and Britain. Many slaves believed the British officers who promised to set them free if they would run away from their masters and help the British. Tens of thousands of black men, women, and children fled their plantations for British camps. Seventeen slaves even ran away from George Washington’s Virginia plantation.

At first the American officers forbade blacks from fighting in the Continental army, but when too many slaves joined the British forces, all states except South Carolina and Georgia allowed slaves to become soldiers. Later, when more troops were needed and there were too few volunteers, citizens were drafted into the army—meaning they had to go. Wealthy men could buy a substitute. Some slaveholders promised to free a slave who would take their place. By 1779, blacks made up about 15 percent of the Continental army, making it the most thoroughly integrated American force until the Vietnam War, two centuries later.

He signed on as a powder monkey for the Royal Louis, the best-known privateer in Philadelphia. It had been built by the Pennsylvania Commonwealth to protect American vessels from British warships that threatened their harbor. Captained by Stephen Decatur, the Royal Louis captured more British ships than any other privateer, and the crew earned more prizes. Best of all, the crew was racially integrated—James would be one of twenty Negroes on board.

James’s main job was to keep the cannons on deck supplied with gunpowder, which was stored below in a dry room called the magazine. Powder monkeys had to be fast, brave, and cool in battle. Usually they were small, too, but James was already nearly six feet tall. But if it didn’t bother Captain Decatur, it didn’t bother James.

James’s courage was tested on his very first voyage, when the Royal Louis met the British ship Active and quickly traded cannon shots. James tucked bags of flammable gunpowder inside his jacket to shield it from flying sparks and sprinted up and down stairs as the ship rocked from cannon blasts. Shells exploded all around. Men screamed in pain and officers shouted to make their orders heard. The ships drew closer and closer until they collided. Americans swarmed aboard the Active, where sailors fought hand to hand. James’s coat was drenched in blood when the British sailors finally gave up.

After a rousing welcome in Philadelphia, the sailors split up the money and headed back to sea. But this time their luck ran out. The Royal Louis went hard after a British ship that led them into a trap. Soon the Americans were surrounded by three British warships and forced to surrender. James was in serious trouble. He had been free in Philadelphia, but now he was a British prisoner. He knew that the British often sold black captives to British sugar plantations in the West Indies. Was he about to become a slave?

James and others were taken aboard a British ship. The British captain, John Beasley, inspected them one by one, moving his way slowly along a line of captives. He stopped when he got to James. His eyes went to a small bag James held in his hand. He asked what was in it. “Marbles,” James replied.

The captain brightened. It so happened that his son, Willie, was aboard. Willie was about James’s age and loved marbles. A game was quickly arranged and the boys became friends. James had learned to shoot expertly from his father’s friends, and, though slavery might be in his future, when it came to marbles, James Forten owned Willie Beasley. Captain Beasley was so impressed that he offered to take James back to England and pay for his education if he would renounce his allegiance to America. James answered without hesitation: “No! I was captured fighting for my country and I will never be a traitor to her.”

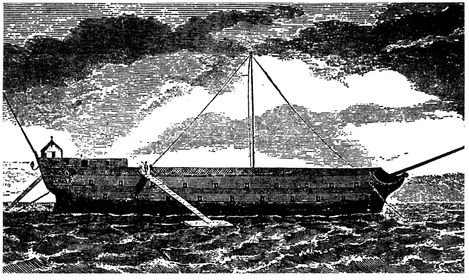

The dreaded British prison ship Jersey, anchored off Long Island, where young James Forten was imprisoned for seven months. During the Revolutionary War more than ten thousand American prisoners died in the ship’s disease-infested hold.

Instead of shipping him to the West Indies, Captain Beasley sent James to the Jersey, a prison ship in New York Harbor. It was more like a death ship. James spent seven months in an airless space below deck and nearly starved. When he was finally traded for another prisoner, his hair had fallen out and he looked like a skeleton. But he was free. “Thus,” James Forten wrote later, “did a game of marbles keep me from a life of West Indian servitude.”

He grew up to be a wealthy and well-known sailmaker and an outspoken opponent of slavery. He hired both blacks and whites at his Philadelphia sailmaking business. He strongly supported women’s rights. Respected by all, he was offered the chance to become president of Liberia, in Africa, but chose to remain in America.

PRIVATEERS

Privateers were privately owned ships allowed by the American government to chase British vessels and keep anything of value they captured. The American navy was very small, but there were more than one thousand privateers that fought in the Revolutionary War, capturing more than six hundred British ships. There was money to be made: In 1779, one fourteen-year-old cabin boy made $700, one ton of sugar, thirty-five gallons of rum, and twenty pounds each of cotton, ginger, logwood, and allspice. But many privateering sailors were killed or captured, and the British treated them harshly.