BETTY ZANE

Though perhaps only Deborah Sampson fought in uniform, many girls and women saw action in the Revolutionary War. In 1782, sixteen-year-old Betty Zane saved the lives of many American soldiers during the siege of Fort Henry, West Virginia. With the fort surrounded by Indians who were fighting on the British side, the Americans ran out of gunpowder. Betty said she knew of a stash of powder in a nearby house. She dashed out of the fort, made it to the house, and emptied a barrel of powder onto a tablecloth. Then she bundled it up and hauled it back to the fort through a hail of bullets, enabling the soldiers to survive.

“Poor Bob is gone.”—Army nurse

Massachusetts and New York, 1779—1782

The war was supposed to be fought by men, but at least one young woman put on—and altered—the uniform of the Continental army. She served for three years in a fighting regiment.

Deborah Sampson was born into a large, poor family in Plymouth, Massachusetts. One day when she was little, her father walked away, leaving her mother with too many children to feed. Deborah was sent to live with a neighbor, and then to the Thomas family, farmers who needed an indentured servant.

In a way, Deborah thought, it wasn’t so bad. She liked hard outdoor work, and the Thomases treated her well enough. But they wouldn’t let her go to school because, they kept saying, school meant too much time away from chores.

Deborah was determined to learn anyway. Some afternoons she slipped down to the road in front of her house and convinced the schoolchildren who passed by to lend her their books overnight. She fell asleep trying to make sense of the words and numbers, but she hustled down to the road the next morning to return the books and ask the students to help her understand what she couldn’t figure out. They did their best to help her, but it wasn’t like having a real teacher.

When Deborah turned sixteen, in 1776, she went to live with another farm family who agreed to give her half a day free to go to school. She was the oldest student, and far behind the others, but she outworked everyone until she caught up. Soon she was assisting the teacher.

Meanwhile the Revolutionary War stormed through New England. Liberty had a special meaning to Deborah, since people had been telling her where to live and what to do all her life. She volunteered to do farmwork for families whose men had gone off to war, but she never felt that she was doing enough. She considered becoming a nurse or a bandage supplier, but she really wanted to fight. It seemed unfair that females

couldn’t enlist. Years of farmwork had made Deborah as strong as most men, and she knew how to handle heavy equipment.

As she worked, a daydream formed and soon began to harden into a plan. She knew she couldn’t join the local militia, where people would recognize her. But soldiers were needed in the Continental army to fight in New York and Pennsylvania. No one knew her there. With money she earned teaching school in the summer, she bought several yards of coarse fabric and sewed a suit of men’s clothing. She hid each piece in a haystack until the whole outfit was finished. Then she told her family that she was leaving to find better wages and hiked off with her clothes tied in a bundle. Once out of sight, she slipped inside a grove of trees, cut her hair, put on her disguise, and walked to Medway, Massachusetts, where a company was forming. She introduced herself to the commander as “Robert Shirtliffe.” Captain Thayer invited young Shirtliffe to live with his family until the company was complete and ready to join the main army. He issued the new soldier a uniform, which didn’t quite fit. Mrs. Thayer was amazed to see Shirtliffe take out a needle and scissors and alter it expertly. The young soldier explained that he had grown up in a family without girls and his mother had made him learn to sew.

When the company was formed, Deborah was assigned to West Point, New York. Action came swiftly. Heading toward Tarrytown, New York, the Continental soldiers were surprised by a fast-moving Hessian cavalry unit. Deborah took her position with her unit and fired again and again. Only when the battle was over did she notice the two bullet holes through her coat and one in her cap. The soldier positioned next to her lay dead. Somehow, Deborah wasn’t seriously hurt.

Deborah Sampson, also known as Robert Shirtliffe, from the cover of her biography

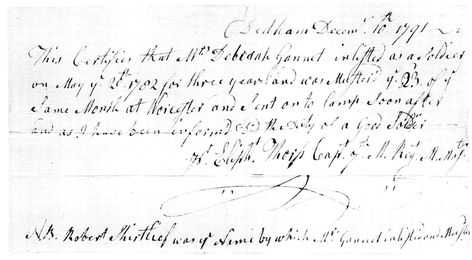

Deborah Sampson’s “muster certificate,” proving to all that she had indeed served as a soldier in the Revolutionary War. By 1791, the date of this document, she was using her married name, Gannet.

For three years she fought the British and managed both to stay alive and to keep her secret. Most of the time it wasn’t so hard. Soldiers rarely bathed and they slept in their uniforms. She kept her hair short. A few noticed that she never seemed to shave and called her Molly, but she felt no need to respond. No one could fault her as a soldier. She was as good as anyone in her company with a musket or bayonet. Often she volunteered to scout possible enemy positions and never backed down in a fight. Twice she was wounded, first by a British sword that slashed the left side of her head and later by a bullet that passed through her shoulder. Both times she was treated with her uniform on.

But in 1782, as the war was winding down, Deborah fell ill. Feverish and unconscious, she was taken on horseback to a field hospital, where the nurse on duty could not detect her pulse. “Poor Bob is gone,” she reported to the doctor. The doctor felt for a heartbeat and discovered a bandage wrapped tightly around the soldier’s chest. Removing it, he got the shock of his career. He kept Deborah’s secret and took her to

his own home, where his family took care of her until she recovered. Only then did he inform her company commander.

Without explanation, Deborah was given an honorable discharge from the army. She went back to Plymouth to help her mother. Word about what Deborah Sampson had done soon spread through her town. Some treated her as a criminal who had deceived her country for three years. She was expelled from her church. At first she was ashamed to have caused problems, but the more she thought about it, the less apologetic she felt. What was there to be ashamed of? She had fought at least as well as the men in her company. She came to feel proud that she had risked her life again and again for her nation and that she had acted boldly for the cause of liberty.

She married and became a schoolteacher. One day, years later, she received a letter addressed to “Robert Shirtliffe, or rather Mrs. Gannet.” It was from George Washington, now president of the United States, inviting her to visit the capital. There, Congress awarded her a pension, land, and a letter thanking her for remarkable service to her country. Later she traveled throughout New York and Massachusetts, telling war stories and showing amazed audiences how well she could handle guns and swords. “I burst the tyrant bonds which held my sex in awe,” she said, “and grasped an opportunity which custom and the world seemed to deny as a natural privilege.”

LIVING IN A LARGE FAMILY

During her military life, Deborah wrote to her mother, artfully concealing her true job. In one letter she said, “I am in a large but well-regulated family. My employment is agreeable though it is somewhat different and more intense than it was at home.”