“Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave?”—Francis Scott Key

Baltimore, Maryland, 1813

Thirteen-year-old Caroline Pickersgill sewed flags with her mother and grandmother in the sunny front parlor of their redbrick house in Baltimore. The floor was strewn with strips of bright wool bunting and half-used spools of thread. Flagmaking was a tradition in Caroline’s family. Her grandmother, Rebecca Young, had made the first flag of the American Revolution. Her mother, Mary Pickersgill, had built up a good business sewing flags and pennants for ships from all over the world that sailed into Baltimore Harbor. During the War of 1812, the Pickersgills were ready for the most important order they ever got.

In the spring of 1813, Major General George Armistead, commander of Fort McHenry, a star-shaped fort that guarded Baltimore Harbor, called at the Pickersgills’ house on Albemarle Street in Baltimore. Caroline Pickersgill, her mother, and her grandmother listened as the general explained that he wanted them to sew the biggest American flag ever made—forty-two feet by thirty. That, they realized, was wider than their whole house. Armistead wanted to raise a giant banner over Fort McHenry so that it would be the first thing the British saw if they ever entered Baltimore Harbor. Such a flag would give his men pride, he said, and let the British know they were attacking a city defended by proud Americans. And one other thing: He needed it right away.

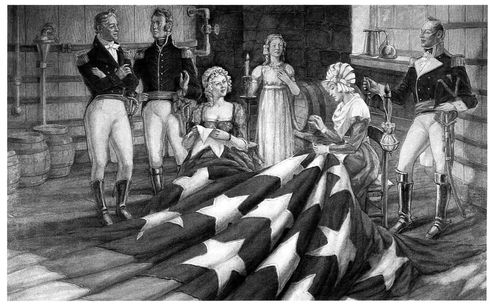

Mary and Caroline Pickersgill work on the star-spangled banner in Claggette’s Malt House, while a cousin watches and Major General Armistead’s soldiers hover impatiently.

A WHOPPER OF A FLAG

The flag the Pickersgills made for Fort McHenry was forty-two feet long and thirty feet wide. It had fifteen stripes and fifteen stars, representing the number of states in the Union at the time. When it was finished, the flag weighed two hundred pounds. It was sewn onto four hundred yards of English wool bunting, which made the Pickersgills feel good. For a fee of $405.90—including the cost of material—the girls and women sewed 1.7 million stitches. Today the original flag is on display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. A restoration project, ending in the year 2000, cost over $18 million.

The Pickersgills quickly agreed. It was a good time to take on a big project, since Caroline’s cousins Eliza Young, thirteen, and Mary Young, fifteen, had just moved in after the death of their father. As soon as enough wool bunting could be purchased, the three girls and two women put away their other projects and began to cut out red and white stripes that quickly bunched up on the floor in Mary’s upstairs bedroom. When it came time to attach the blue field (for the stars) to the stripes, they had run out of space.

They carried the stripes several blocks to a neighborhood brewery and into a large winter malt room that was unused during hot months. After shoving kegs of beer back against the walls, they swept the floor clean and laid out the material. They worked at top speed from dawn till midnight six days a week, often with Major General Armistead’s men hovering over them.

In September they finally attached a blue rectangular square to the stripes, and then cut out fifteen stars and stitched them to the flag, spacing them carefully. When the flag was finished, two soldiers folded it, stuffed it into a duffel bag, and hauled it to the fort in a cart. They tied it to a stout pole and raised it aloft as the Pickersgills watched. As it neared the top, the banner unfurled in the wind, forming a colossal symbol of patriotism. The giant flag was visible not only from the harbor but from just about every window in Baltimore.

The British didn’t arrive until nearly a year later. In August 1814, they sailed an army into Chesapeake Bay near Washington, D.C., just thirty miles to the south. After easily winning a battle, redcoats torched the president’s house and burned down the Capitol. When Baltimoreans heard the news, they worked feverishly to fortify their city. Outside her windows, Caroline could hear the drums and fifes of militiamen drilling on the common. Slaves and masters labored side by side, digging trenches and rolling cannons toward Baltimore Harbor. The great explosions that rocked Caroline’s house meant that ships were being sunk in a great semicircle in Baltimore Harbor to form a barrrier against sea invasion. Though many Baltimore families were dragging their belongings into the countryside, the Pickersgills prepared to face the crisis from their home. It wouldn’t be long now.

The first British ships arrived around noon on Sunday, September 13, 1814. When officers realized their path to the city was blocked by sunken ships, they attacked Fort

McHenry with powerful cannons that could send shells two miles. The Pickersgills’ home shook all night and into the next day. Caroline and her family watched the fireworks from their attic. For a while, they could see their flag from a window, but then heavy rainclouds obscured it and darkness came.

Out in the harbor, an American lawyer named Francis Scott Key was trapped aboard one of the British gunships, where he had been trying to arrange a prisoner exchange between the two sides. Unable to leave, all Key could do was watch the British rockets light up the sky. The most visible object, lit up with each blast, was the Pickersgills’ giant flag. But then, deep into the rainy night, the British stopped shelling the fort. There was an eerie silence. What had happened? Was Fort McHenry still standing? Was the flag still there? Key began nervously to make up new lyrics to an old English drinking tune. “Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave?” he wrote.

Dawn came, and there was the flag, tattered and riddled with holes, but still rippling over the fort. Overnight the tide of battle had turned: Now Baltimore’s militia was routing the British forces. Soon the Americans had won a decisive victory.

News of the battle of Fort McHenry, of the giant flag, and of the words to Key’s new song spread quickly, inspiring Americans all over the country. On December 24, 1814, in Ghent, in what is now Belgium, the British agreed to a peace treaty. It took another six weeks for word to reach the United States from Europe, during which time many more soldiers died. Though they never fired a shot, Caroline Pickersgill and her family had the satisfaction of knowing they had helped secure their new nation’s future.

At nineteen she married an iron merchant named John Purdy. The couple had no children. Caroline inherited her mother’s house in 1857 and sold it seven years later when she needed money. She died in poverty in 1881. Today her home, called the Flag House, is a National Historic Landmark on Albemarle Street in Baltimore.