“I thought [writing the Cherokee language] would be like catching a wild animal and taming it.”—Sequoyah

Southeastern United States, 1820s and 1830s

As white settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains and pushed westward, eastern tribes tried to stop them from chipping away at their homeland. Shawnees, Seminoles, Creeks, and other tribes fought valiantly, but they were outnumbered and outgunned. Treaty after treaty was broken, and Native Americans were pushed back bit by bit.

One tribe tried something different. The Cherokees decided to imitate white ways. They took on white names. Many became Christians. They tore down their stick-and-wattle structures and /earned how to build log cabins and brick houses. Most important, a Cherokee named Sequoyah (who took the name George Guess) and his young daughter, Anyokah, developed an alphabet of syllables that gave Cherokees a written language.

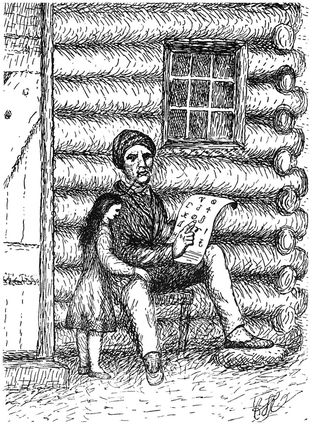

Anyokah was a solitary, dark-haired girl of six when she began to work on the alphabet with her father. She was the only member of the family—and, in fact, the only person at all—who showed even a spark of interest in her father’s project. But that wasn’t surprising. Despite the difference in their ages, Sequoyah and Anyokah were very much alike: Both were dreamers, both hard workers, and both visionaries. One writer who observed them as they worked together reported that Anyokah simply “seemed to enter into the genius of her father’s labor.”

Most Cherokees thought Sequoyah was wasting his time trying to “speak at a distance,” but he barely noticed their criticism. He and Anyokah were too busy. At first they tried to make a list of all the sounds in the Cherokee language and then to draw a picture of each. Anyokah’s hearing was better than Sequoyah’s, and she suggested new sounds to add to the vocabulary. When they agreed on a sound, he painted the sound’s image onto a wooden shingle. At one point Anyokah’s mother became so disgusted with the all-consuming project that she set fire to the piles of shingles. Sequoyah quietly wandered away from the house for a while. Maybe the fire was a blessing, he concluded; the idea wasn’t really working anyway.

The next idea was to make a list of all the syllables that were commonly spoken by Cherokees. To make the whole vocabulary easier to learn, they needed the smallest possible number of syllables. Sequoyah and Anyokah listened constantly as people spoke, barely paying attention to what they were saying but quickly writing down any new syllable they heard. At first there were about two hundred syllables, but Anyokah kept reminding her father that they had heard some of them before. Finally they whittled the list down to eighty-six distinctive syllables, giving each its own symbol, many of which were English letters.

CHEROKEE WORDS

| English | Cherokee | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| Amen |  |

e-me-nv |

| baby |  |

u-s-di-ga |

| bad |  |

u-yo-i |

| bed |  |

ga-ni-si |

| bird |  |

tsi-s-qua |

| boy |  |

a-tsu-tsa |

| bread |  |

ga-du |

| bridge |  |

a-sv-tsi |

| cat |  |

we-sa |

| chair |  |

ga-s-gi-lo |

| chicken |  |

tsa-ta-ga |

| corn |  |

se-lu |

| day |  |

i-ga |

| dog |  |

gi-li |

| earth |  |

e-lo-hi-no |

| father |  |

e-do-da |

| flower |  |

u-tsi-lv-ha |

| forest |  |

a-do-hi |

| friend |  |

o-gi-na-li-i |

| girl |  |

a-ge-yu-tsa |

| God |  |

e-do-da |

Anyokah helping her father, Sequoyah, create the Cherokee syllabic alphabet

In 1821, Sequoyah and ten-year-old Anyokah mounted horses and rode from Arkansas to New Echota, Georgia, to show the written language to the Cherokee Tribal Council. At first the tribal leaders wouldn’t even allow them to demonstrate it. They laughed at the idea that marks on a piece of deerskin could actually carry messages that everyone could read. Sequoyah proposed a test: He would leave the room. They could tell Anyokah anything they wanted and she would write it down. Then Sequoyah would come back, look at the marks on the skin, and tell them what they had said. It worked again and again. The first few times the elders called it luck, but gradually doubt gave way to excitement. Soon thousands of Cherokees wanted to learn how to read. The syllabic alphabet led to the preservation of the Cherokee language and then to the first American Indian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Before long schoolchildren were learning to read in both Cherokee and English. The letters were called talking leaves.

For a while, the ability to read and write helped Cherokees to prosper above all other tribes. They wrote a constitution and built an impressive capital city. Some Cherokees owned huge farms and lived in plantation-style homes. Some owned slaves. They built schools and planted orchards. But not even the power of literacy could keep whites from driving the Cherokees from their land after gold was discovered in a part of Georgia. In the warm May of 1838, the Cherokees went the way of the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Seminoles, and Creeks before them—west. Seven thousand U.S. soldiers were sent to Cherokee country with orders to round up every Cherokee man, woman, and child and drive them from the land. Men were ordered at gunpoint from their plows and women from their looms. Children at play were motioned into wagons by long steel rifle barrels. They were to leave their things behind and get moving.

The Cherokees were herded into camps and then driven on foot or in wagons eight hundred miles to what is now Oklahoma. Many died before they got there. The journey was called the Trail of Tears. One elder who was five years old on the leaving day recalled that he had been playing in his front yard when the wagon came and the soldiers told him to get in. He gathered up his toys, but the soldiers made him leave them in the dirt. By the time the wagon pulled out, he could see that a white boy had already moved in and was playing with them.

Little is known of her after she helped her father demonstrate the syllables to the elders. It is not known if she married. If she did, and married a white man, she might have been allowed to remain in the Southeast. If she married an Indian, she would have probably been forced west on the Trail of Tears.

A PLAIN-SPOKEN QUESTION

“What good man would prefer a county covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns and prosperous farms … occupied by more than twelve million happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?”

—President Andrew Jackson, explaining to Congress why Indians should be removed from their land, 1830