‘Anyone who secretly enters into a ship and is later detected will be put to death.“—Sign posted on the Japanese coast, 1851

Japan and Massachusetts, 1840s

In the nineteenth century, Japan was a feudal society closed to the other nations of the world. Her leaders drew up the Decree of Exclusion, which said, “So long as the sun shall warm the earth, let no Christian dare to come to Japan … If he violates this command [he] shall pay for it with his head.” Japanese citizens were forbidden from travel and contact with outsiders. Most obeyed without question, and a boy named Manjiro would have, too, if a gust of wind and a whaling ship hadn’t delivered him into another world.

On January 5, 1841, the year of the cow, five Japanese fishermen put out from a tiny port named Usa at the southwest corner of their island. The youngest, Manjiro, was a boy of fourteen. As a peasant child, Manjiro rated only one name and had no hope of ever going to school. His father was dead and his mother was too poor even to send him to a Buddhist temple for lessons, so he went to sea with fishing crews to help support his family. On this day, he and his mates were bound for the rich Kuroshio current. They had enough rice, firewood, and fresh water to stay out for several weeks.

Manjiro at age twenty-seven

ALONE IN THE WORLD

In the 1630s, Japan’s leaders decided to cut off contact with other nations to keep order in Japan. Japan became isolated for more than two hundred years, adopting a rigid form of feudalism. The country was ruled by the emperor and the shogun—a military leader. There were 250 daimyo (lords), many samurai (knights), and then the rest of the people, who were broken up into classes. Everything from your name to your food to your clothes to the way you made your living was determined by the rank of your parents. Manjiro, the son of peasants, was of the lowest class.

But the trip seemed jinxed from the start. For six days the crew hauled in nothing but empty nets, and on the seventh day the sky turned deep purple and gusts of wind whipped the sea in circles. As they struggled for land, they came at last upon a great school of fish. Unable to resist, they stopped rowing and tossed out their nets. But soon mountainous waves washed away all their oars but one. Then the rudder snapped and they were swept onto a rocky, uninhabited island many miles from shore. There they lived by killing albatross and drinking rainwater that had collected in the hollows of rocks.

After six months they spotted a ship far in the distance. While the others hesitated, Manjiro stripped naked and swam toward the vessel. He was spotted by a crew member of the John Howland, a whaling ship from Massachusetts. Soon all five Japanese fishermen were safely aboard. A few days later, Manjiro, refreshed, watched from the deck as the Howland’s crew chased and killed a sperm whale and then cut the animal up and drained it of oil. He remembered the elders in his village saying that seven ports would thrive with the catch of one whale. He thought that if he could master the whaling techniques of these foreigners, he could feed seventy Japanese ports.

The whaler’s captain, William Whitfield, was impressed by Manjiro: He was strong, fearless, and eager to learn. He never ran out of questions about how things worked. Once, when they came upon a giant sea turtle, Manjiro dived into the water and killed the creature with a knife. When they reached Hawaii, Whitfield let the other four Japanese off, but he took Manjiro around the tip of South America to his home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. As they sailed into the American harbor, Manjiro saw wide streets lined with white-framed houses and a towering church steeple. On shore, women walked in bonnets, muslin ruffs, and hoop skirts. At fifteen, Manjiro had become the first Japanese to reach the United States.

Whitfield gave him a new name—John Mung—since, he explained, all Americans had two names. John enrolled in a school—something a peasant couldn’t do in Japan—and quickly outshone the other pupils by outworking them. One Sunday, Captain Whitfield proudly took John to church, where they sat together in the captain’s front pew. After the service, the deacon informed Captain Whitfield that from then on John would have to sit

with the Negroes in the back. Captain Whitfield changed churches twice until he found a Unitarian minister who would agree to accept John as an equal.

John might have settled in New England, but at heart he was a Japanese patriot with a huge goal: He wanted to bring Japan into the modern world of ideas and machines by showing them American technology. He mastered math and navigation, often staying up all night to study. As an apprentice, he learned to make barrels that held whale oil. He told himself that the more he learned, the more he could do for Japan.

His first problem was to get enough money to go back home. He worked on a whaling ship but earned way too little. Then he traveled to the California goldfields, hoping his luck would change. One day, while panning in a river, John spotted a glittering nugget about the size of an egg. He looked around to make sure no one was watching and then buried it in the ground and sat on it all night. He sold it for six hundred dollars the next day and bought a boat to sail back to Japan.

In January of 1851, after weeks at sea, twenty-four-year-old Manjiro and two others approached the coast of Japan. When they landed, they saw a sign that read: “The sending of ships to any foreign country is hereby forbidden. Anyone who secretly enters into a ship and is later detected will be put to death. Any person who leaves the country to go to another and later returns, then he, too, shall meet with the same fate.” Manjiro—a young man from the very bottom level of Japanese society—had clearly broken his country’s most sacred law.

The handful of fishermen who first encountered Manjiro and his companions pretended they couldn’t understand him. They took Manjiro to a local official, who promptly took him to a higher official. For two years he was questioned by authorities who asked the same things over and over. Again and again he stomped on a picture of Jesus Christ to prove he wasn’t a Christian. He was even summoned to tell his story to the shogun. There is no record of their conversation, but some historians think Manjiro influenced officials favorably toward Americans who wanted to trade with Japan. In the next few years the Japanese rulers’ curiosity about American technology finally overcame their caution. In 1860, John Mung, as he was now called even in Japan, was permitted to return to America with the first official Japanese trade delegation to the United States.

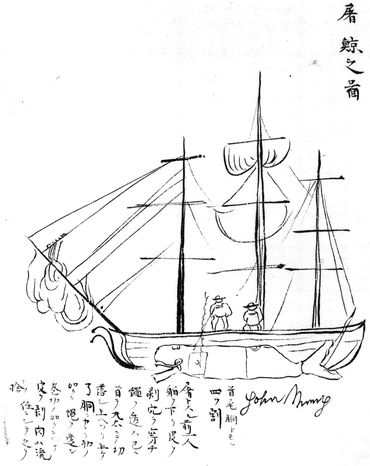

Among his many talents, Manjiro became an accomplished artist. He entitled this brush-and-ink drawing Cutting-in a Whale.

After two years in Japan, he was finally allowed to return to his village and visit his mother. After greeting him, townspeople took Manjiro to see his own cemetery stone. He stayed in Japan and became an English teacher, instructing high Japanese officials. He also worked as a whaler, shipbuilder, interpreter, and translator.