THREE-FIFTHS OF A PERSON

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Southern delegates claimed that slaves were not people but property, like cattle, and therefore slaveowners shouldn’t have to pay taxes on them. On the other hand, Southerners wanted slaves to count as part of a state’s population, since the more people a state had, the more representatives it had in Congress. A compromise was reached: In matters of both taxation and representation, slaves would count as three-fifths of a person.

“How I escaped death, I do not know.”

Maryland, 1833

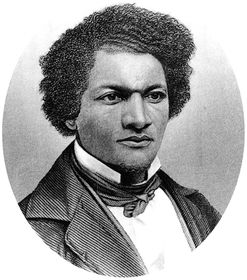

Frederick Douglass, the best-known black leader of the nineteenth century, was a slave until he was twenty. Later, in his widely read autobiography, he wrote about his yearning to know his parents, his struggle to read, and a life-changing wrestling match with his brutal master. He wrote that one thought dominated his boyhood: “Why am I a slave?” Finally, he decided, “I will not stand it. I have only one life to lose. I had as well be killed running as die standing.”

Whenever people on the Lloyd tobacco plantation on the Eastern Shore of Maryland wanted to make Frederick Douglass mad, they told him that his father was really Master Anthony, the plantation overseer. Frederick denied it angrily, but deep down he suspected that maybe they were right.

His mother, whose name was Harriet Bailey, was almost as mysterious to him. She had been sold to another plantation when Frederick was a baby, but sometimes she slipped away at dark and hiked twelve miles through forests and fields just to hold him for a few hours. He never knew when to expect her. “I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day,” Douglass wrote later. “She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.” Her last visit came when Frederick was about seven. Only years later did he find out for sure she had died.

At the age of ten Frederick became a gift to a wealthy white boy. He was sent off to Baltimore to be a companion to young Thomas Auld. Life at the Auld house was soft compared to the Lloyd plantation: “Instead of the cold, damp floor of my old master’s kitchen, I was on carpets; for the corn bag in winter, I had a good straw bed, furnished with covers.” And the work was light, too—all Frederick had to do was run errands and keep Tommy Auld out of trouble.

Best of all, Tommy’s mother, Sopha, gave the boys reading lessons every afternoon. Frederick couldn’t believe his good luck. “In an incredibly short time I had mastered the alphabet and could spell words of three or four letters.” Things were going beautifully until the night that Sopha proudly told her husband how quickly Frederick was learning to read. Hugh Auld exploded. “If he learns to read the Bible,” Auld sputtered, “it will forever

unfit him to be a slave. He should know nothing but the will of his master, and learn to obey it.” The lessons stopped at once.

But it was too late. Frederick had discovered that “knowledge unfits a child to be a slave,” and he was determined to be free. But now he had to learn on the sly. “When my mistress left me in charge of the house,” he later wrote, “I had a grand time. I got Master Tommy’s copy books and a pen and ink, and in the ample spaces between the lines I wrote other lines as nearly like his as possible. I ran the risk of getting a flogging.” Late at night, while the Auld family snored, Frederick quietly spread out paper on a flour barrel and copied words from the Bible.

When daylight came, he found white children on the street and traded them bread for reading lessons. To improve his writing he wrote out letters on paper and told them they couldn’t write half as well as he could. They always grabbed the pen and wrote with their best handwriting. Then Frederick took the paper home and tried to match it.

The Aulds sent Frederick back to the plantation, where he began teaching other slaves to read and write during Sunday-school classes. Word got around quickly. One Sunday the door burst open and “in rushed a mob … who, armed with sticks and other missiles drove us off, and commanded us never to meet for such a purpose again.” One man threatened to fill Frederick with bullet holes if he ever caught him teaching a slave to read again.

To tame his spirit, Frederick was sent to live with a tough local farmer named Edward Covey. Every slave around knew Covey. He was a poor Methodist minister who rented his land and worked his slaves brutally hard. Lean and tough, Covey prized his reputation as a “slave-breaker.” He had all sorts of methods. He worked his field hands from sunup to sundown. He spread plenty of food out before them at break time, but then ordered them back to work before they could finish it. Slaves called him the Snake, because he hid in the bushes and watched them, waiting for someone to stop working so he could spring out and punish them.

Frederick Douglass wrote that during his first six months with Edward Covey, he was “whipped either with sticks or cowskins every week.” Like the man pictured here, Douglass’s back bore the signature of slavery for the rest of his life.

CAUTION: TEACH AT YOUR OWN RISK

“If any person shall hereafter teach any slave to read or write … such person, if a free white person, upon conviction thereof, shall, for each and every offence against this Act, be fined not exceeding one hundred dollars, and imprisoned not more than six months; or if a free person of color, shall be whipped, not exceeding fifty lashes, and fined, not exceeding fifty dollars.”

—South Carolina law, 1834

How OLD AM I?

“I do not remember a slave who could tell his birthday. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege.”

—Frederick Douglass

But mainly he just beat them. Less than a week into the job, Covey whipped Frederick so hard with a pointed tree branch that he raised welts “as large as my little finger” on Frederick’s bloody back.

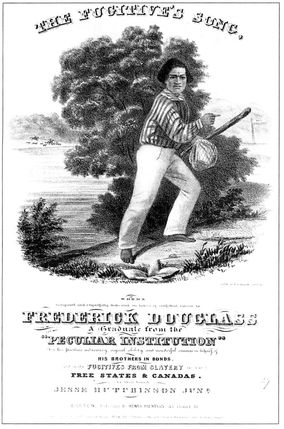

In 1845, songwriter Jesse Hutchinson, Jr., wrote “The Fugitive’s Song” to honor all slaves who had dared bolt for liberty. He dedicated it to Frederick Douglass, and it became a mainstay of antislavery meetings.

A few weeks later, Frederick passed out while working in a field under a boiling August sun. Covey woke him up with a series of brutal kicks and then smashed him in the head with a hickory stick for good measure.

When he recovered, Frederick fled from the farm and considered his options. None seemed very good. First he went to his old master and asked to be taken back. The man refused. Then he thought about trying to escape north, but he didn’t know anyone who could help him. Reluctantly, he decided to go back and stand his ground even if Covey killed him. When Frederick walked into the yard on a Sunday, Covey greeted him with a broad smile. He asked Frederick gently if his head still hurt and gave him extra food. But the next morning Covey slipped up behind him, tripped him, and tried to get a noose around his ankles. Breathing hard, Frederick leaped away and spun around to face Covey. Frederick was only sixteen, but he was tall and strong. It was now or never.

“Whence came my daring spirit I do not know,” he later wrote. “The fighting madness had come upon me and I found my strong fingers firmly attached to the throat of my cowardly tormentor … as though we were equals before the law. The very color of the man was forgotten. I felt as supple as a cat, and was ready for the snakish creature at every turn. I flung him to the ground several times. I held him so firmly by the throat, that his blood followed my nails. He held me and I held him.”

They wrestled nonstop for two hours. At one point, Frederick hurled Covey into a pile of cow manure. The fight finally ended with Covey walking away and pretending he had won. Frederick let him go. They both knew the real score. “The fact was … he had not drawn a single drop of blood from me. I had drawn blood from him.” Frederick lived with Covey for six more months, but Covey never challenged him again. Frederick always thought it was because Covey didn’t want word to get around that a slave had stood up to him. Frederick later called the fight the turning point of his life. “I was nothing before,” he wrote. “I am a man now.”

Disguised as a sailor, he escaped to Massachusetts when he was twenty. He opposed slavery in speeches, in his newspaper, the North Star, and in a widely read autobiography. In the Civil War, he helped recruit black soldiers for the Union army, including two of his sons. He had the respect, and the ear, of President Lincoln throughout the war.

WORK, WORK, WORK

“We were worked in all weathers. It was never too hot or too cold; it could never rain, blow, hail, or snow too hard for us to work in the field. Work, work, work … The longest days were too short for [Covey], and the shortest nights too long for him.”

—Frederick Douglass